Published online May 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i15.2621

Revised: February 10, 2024

Accepted: April 7, 2024

Published online: May 26, 2024

Processing time: 113 Days and 18.6 Hours

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding is a common medical emergency that has a 10% hospital mortality rate. According to the etiology, this disease can be divided into acute varicose veins and nonvaricose veins. Bleeding from esophageal varices is a life-threatening complication of portal hypertension. Portal hypertension is a clinical syndrome defined as a portal venous pressure that exceeds 10 mmHg. Cirrhosis is the most common cause of portal hypertension, and thrombosis of the portal system not associated with liver cirrhosis is the second most common cause of portal hypertension in the Western world. Primary myeloproliferative disorders are the main cause of portal venous thrombosis, and somatic mutations in the Janus kinase 2 gene (JAK2 V617F) can be found in approximately 90% of polycythemia vera, 50% of essential thrombocyrosis and 50% of primary myelofibrosis.

We present a rare case of primary myelofibrosis with gastrointestinal bleeding as the primary manifestation that presented as portal-superior-splenic mesenteric vein thrombosis. Peripheral blood tests revealed the presence of the JAK2 V617F mutation. Bone marrow biopsy ultimately confirmed the diagnosis of myelo

In patients with acute esophageal variceal bleeding due to portal hypertension and vein thrombosis without cirrhosis, the possibility of myeloproliferative neoplasms should be considered, and the JAK2 mutation test should be performed.

Core Tip: Emergency physicians often encounter patients with acute esophageal variceal bleeding and portal vein thrombosis. We hope that this case report can increase the awareness that in patients who present with variceal bleeding without liver cirrhosis, myeloproliferative neoplasms such as myelofibrosis with the JAK2 V617F mutant, can be identified and treated early to minimize the consequences and avoid bleeding.

- Citation: Chen Y, Kong BB, Yin H, Liu H, Wu S, Xu T. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to portal hypertension in a patient with primary myelofibrosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(15): 2621-2626

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i15/2621.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i15.2621

Acute esophageal variceal bleeding is a common complication in patients with cirrhotic portal hypertension[1]. However, the most common cause of noncirrhotic portal hypertension is portal and splenic vein thrombosis[2]. Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), such as polycythemia vera, essential thrombocytosis, myelofibrosis or unclassified myeloproliferative diseases, can predispose patients to splanchnic vein thrombosis.

Myelofibrosis, a myeloproliferative neoplasm, is characterized by stem cell-derived clonal myeloproliferation, bone marrow fibrosis, anemia, massive splenomegaly and extramedullary hematopoiesis. Primary myelofibrosis patients have a relevant and life-threatening risk of thrombosis[3]. According to a meta-analysis, the prevalence of MPN in Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) and portal vein thrombosis (PVT) patients are approximately 30%-50% and 15%-30%, respectively[4].

The JAK2 V617F mutation is a common gain-of-function mutation leading to the development of MPN. This mutation is present in approximately 50% of patients with primary myelofibrosis and essential thrombocythemia and in nearly all patients with polycythemia vera[5,6]. The JAK2 V617F mutation may predispose patients to portal vein thrombosis.

A 69-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with complaints of hematemesis (approximately 100-200 mL of blood), accompanied by chills and hematochezia (approximately 100 mL of blood), transient blurred vision, no acid reflux, and no abdominal pain.

On admission, her consciousness was clear. The patient had a massive upper bleeding episode on the first day, accompanied by tachycardia, tachypnea, cool clammy skin, hypotension and confusion. No signs of chronic liver disease or autoimmune liver disease were identified.

She had a history of hypertension and thrombocythemia 4 years prior.

The patient had no significant prior family history.

She had a blood pressure of 106/53 mmHg and a heart rate of 86 beats/min upon arrival at the emergency room.

Laboratory data were shown in Table 1.

| Examination item | Data |

| Hematology | |

| WBC | 41.5 × 109/L |

| Hb | 148 g/L |

| Plt | 1181 × 109/L |

| NEUT% | 87.6% |

| CRP | 2.24 mg/L |

| Serological test | |

| Hepatitis B | Negative |

| Hepatitis C | Negative |

| Blood chemistry | |

| ALT | 22.3 U/L |

| D-BIL | 4.5 umol/L |

| ALB | 33.2 g/L |

| BUN | 13.1 mmol/L |

| Cre | 95 umol/L |

| K | 6.87 mmol/L |

| LDH | 375 U/L |

| Ammonia | 173.1 umol/L |

| Autoantibodies | |

| ANA/AMA-M2 | Negative |

| SLA/LKM-1 | Negative |

| LC-1/anti-gp210 | Negative |

| SP100/SMA | Negative |

| Coagulation | |

| PT | 15.1 s |

| APTT | 35 s |

| Fbg | 2.26 g/L |

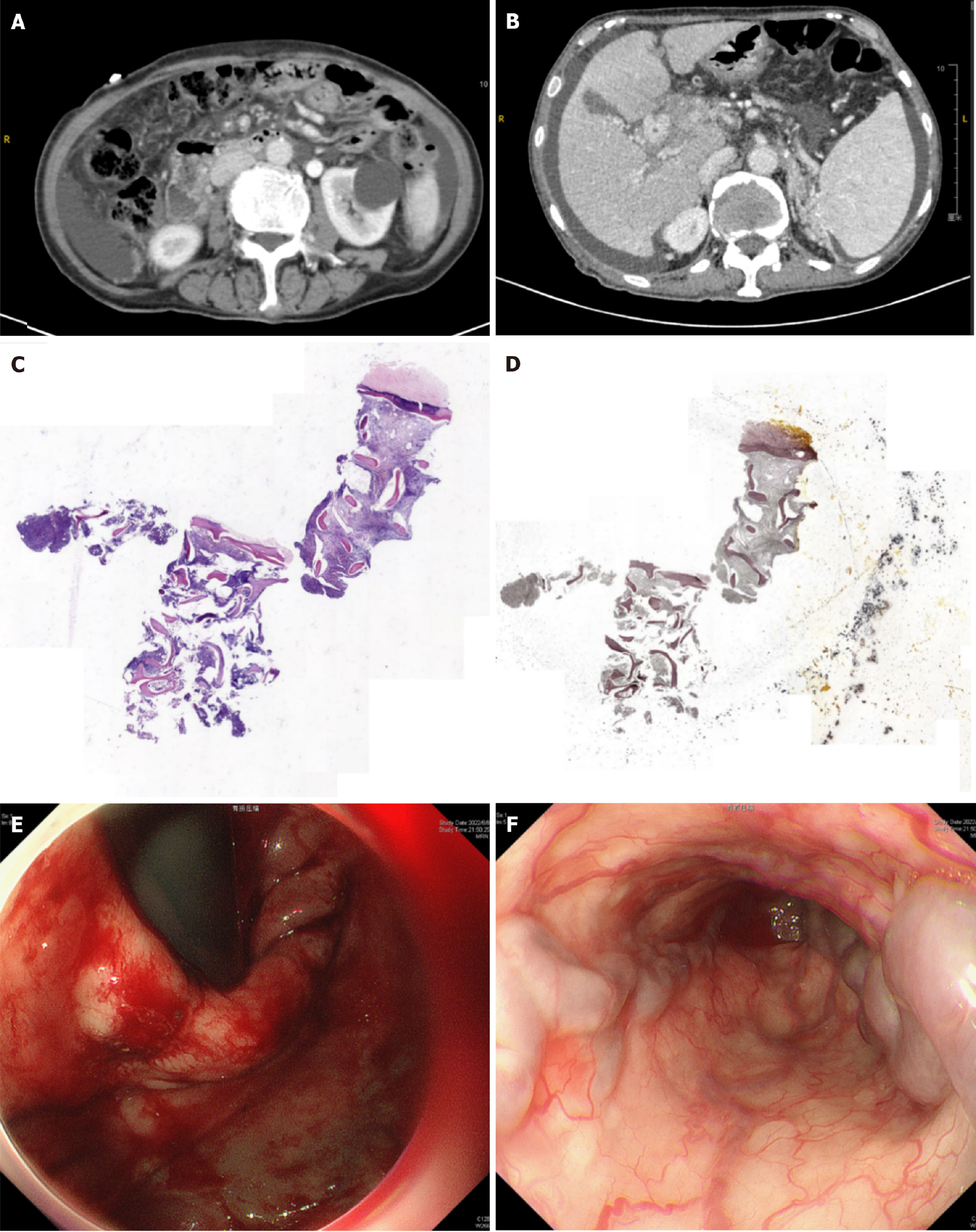

Examinations images were shown in Figure 1.

The final diagnosis of the patient in the present study was primary myelofibrosis with acute esophageal variceal bleeding combined with splanchnic vein thrombosis (SVT).

The first endoscopic variceal ligation with a rubber band and endoscopic injection sclerotherapy with tissue glue were carried out successfully on the first day after admission. After gastrointestinal bleeding stabilized, the patient was discharged on long-term oral ruxolitinib (10 mg, twice a day) for the treatment of myelofibrosis and hydroxyurea platelet-lowering therapy.

After 4 months, the patient experienced esophageal variceal hemorrhage again, and the emergency endoscopist performed emergency endoscopic esophageal variceal band ligation. At present, the patient has long been a follow-up patient in the Hematology Department of our hospital.

Acute esophageal variceal bleeding is a medical emergency associated with high morbidity and mortality and is a serious complication of portal hypertension (PH), usually due to cirrhosis[7]. The most serious complication of portal hypertension is acute variceal bleeding. Endoscopy plays a pivotal role in the diagnosis and risk assessment of bleeding via esophageal varices. In adults, cirrhosis accounts for more than 90% of PH patients; nevertheless, the second most common cause is portal vein thrombosis in the Western world[8]. PVT is defined as a partial or complete obstruction of the portal vein by a thrombus resulting in impeded blood flow[9]. PVT is caused by both local (such as malignant tumors, infection, and cirrhosis) and systemic risk factors (myeloproliferative disorders, antiphospholipid syndrome, and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria) and is identified in 30% and 70%, respectively[10]. Overall, patients with PVT, which has an incidence of 30% to 40%, are affected by chronic myeloproliferative diseases, usually polycythemia vera, essential thrombocytosis, myelofibrosis or unclassified myeloproliferative diseases[11]. Myelofibrosis is characterized by stem cell-derived clonal myeloproliferation, bone marrow fibrosis, anemia, splenomegaly, and extramedullary hematopoiesis[12,13]. In a retrospective study involving 181 patients, primary myelofibrosis (n = 47), essential thrombocythaemia (n = 67) or polycythaemia vera (n = 67) were identified, and SVT was the primary clinical manifestation. PVT and BCS were found in 60.3% and 17.1%, respectively; correspondingly, thrombosis of the mesenteric or splenic veins was diagnosed in 10% and 13%, respectively[12]. We present a rare case of primary myelofibrosis with gastrointestinal bleeding as the primary manifestation that presented as portal-superior-splenic mesenteric vein thrombosis. Myeloproliferative neoplasms are the most common cause of splanchnic vein thrombosis in the absence of cirrhosis or nearby malignancies. These conditions have a common pathogenesis and are derived from JAK-STAT pathway activation through the presence of the JAK2 gene calreticulin. JAK2 V617F-positive myeloproliferative disorders are a less common etiology of abdominal vein thrombosis. Approximately 90% of polycythemia vera strains are positive for the V617F mutant JAK2 protein, and 50% of these patients have primary myelofibrosis and essential thrombocytosis[14]. The presence of the JAK2 V617F mutation facilitates the formation of thrombosis. JAK2 V617F can increase megakaryocyte ploidy and mobility and platelet aggregation, leading to increased thrombotic formation[15]. Therefore, JAK2 V617F can be a prognostic indicator of vein thrombosis in patients with myeloproliferative disorders. Ruxolitinib is a selective inhibitor of Janus kinase (JAK)1/JAK2 approved by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of intermediate- and high-risk myelofibrosis[16]. JAKs play a critical role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and hematopoietic cytokines and immune-mediated disorders, such as through the inhibition of interleukin-6 signaling and the proliferation of JAK2 V617F-positive Ba/F3 cells[17,18]. According to the results of clinical studies, 59% of patients in the ruxolitinib subgroup had a ≥ 35% reduction in the spleen volume in patients with myelofibrosis-related splenomegaly, and ruxolitinib was effective in patients with and without the JAK2 V617F mutation[19,20]. After we added ruxolitinib, extramedullary hematopoiesis was suppressed, and the number of white blood cells decreased gradually.

When patients with acute esophageal variceal bleeding and PVT are observed in the Emergency Department, multiple concurrent risk factors for thrombosis, such as JAK2-related SVT, should be checked for in all patients without advanced cirrhosis or cancer. Thrombosis of the portal vein, splenic vein and superior mesenteric vein may be the initial manifestation of primary myelofibrosis, even in the early stages of the disease. The presence of the JAK2 mutation is a crucial prothrombotic risk factor that can contribute to large venous thrombosis.

We would like to thank the patient. We extend our thanks to the Gastroenterology, Radiology, and Pathology Departments of the Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital for facilitating the acquisition of the relevant materials.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Emergency medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C

Novelty: Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade C

P-Reviewer: Atta H, United States S-Editor: Che XX L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang XD

| 1. | Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in over 16s: management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2016 Aug- . [PubMed] |

| 2. | Valla DC, Condat B, Lebrec D. Spectrum of portal vein thrombosis in the West. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17 Suppl 3:S224-S227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Barbui T, Ghirardi A, Carobbio A, Masciulli A, Carioli G, Rambaldi A, Finazzi MC, Bellini M, Rumi E, Vanni D, Borsani O, Passamonti F, Mora B, Brociner M, Guglielmelli P, Paoli C, Alvarez-Larran A, Triguero A, Garrote M, Pettersson H, Andréasson B, Barosi G, Vannucchi AM. Increased risk of thrombosis in JAK2 V617F-positive patients with primary myelofibrosis and interaction of the mutation with the IPSS score. Blood Cancer J. 2022;12:156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Smalberg JH, Arends LR, Valla DC, Kiladjian JJ, Janssen HL, Leebeek FW. Myeloproliferative neoplasms in Budd-Chiari syndrome and portal vein thrombosis: a meta-analysis. Blood. 2012;120:4921-4928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Spivak JL. Narrative review: Thrombocytosis, polycythemia vera, and JAK2 mutations: The phenotypic mimicry of chronic myeloproliferation. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:300-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Leebeek FW, Smalberg JH, Janssen HL. Prothrombotic disorders in abdominal vein thrombosis. Neth J Med. 2012;70:400-405. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Zuckerman MJ, Elhanafi S, Mendoza Ladd A. Endoscopic Treatment of Esophageal Varices. Clin Liver Dis. 2022;26:21-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Turco L, Garcia-Tsao G. Portal Hypertension: Pathogenesis and Diagnosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2019;23:573-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Margini C, Berzigotti A. Portal vein thrombosis: The role of imaging in the clinical setting. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:113-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Basit SA, Stone CD, Gish R. Portal vein thrombosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2015;19:199-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | DeLeve LD, Valla DC, Garcia-Tsao G. Vascular disorders of the liver. Hepatology. 2009;49:1729-1764. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 739] [Cited by in RCA: 647] [Article Influence: 40.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | De Stefano V, Vannucchi AM, Ruggeri M, Cervantes F, Alvarez-Larrán A, Iurlo A, Randi ML, Pieri L, Rossi E, Guglielmelli P, Betti S, Elli E, Finazzi MC, Finazzi G, Zetterberg E, Vianelli N, Gaidano G, Nichele I, Cattaneo D, Palova M, Ellis MH, Cacciola E, Tieghi A, Hernandez-Boluda JC, Pungolino E, Specchia G, Rapezzi D, Forcina A, Musolino C, Carobbio A, Griesshammer M, Barbui T. Splanchnic vein thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms: risk factors for recurrences in a cohort of 181 patients. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6:e493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tefferi A. Primary myelofibrosis: 2012 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:1017-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Koschmieder S. How I Manage Thrombotic/Thromboembolic Complications in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Hamostaseologie. 2020;40:47-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fleischman AG, Tyner JW. Causal role for JAK2 V617F in thrombosis. Blood. 2013;122:3705-3706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Harrison C, Kiladjian JJ, Al-Ali HK, Gisslinger H, Waltzman R, Stalbovskaya V, McQuitty M, Hunter DS, Levy R, Knoops L, Cervantes F, Vannucchi AM, Barbui T, Barosi G. JAK inhibition with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:787-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1274] [Cited by in RCA: 1410] [Article Influence: 108.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Arana Yi C, Tam CS, Verstovsek S. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib in the treatment of patients with myelofibrosis. Future Oncol. 2015;11:719-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Quintás-Cardama A, Kantarjian H, Cortes J, Verstovsek S. Janus kinase inhibitors for the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasias and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:127-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Verstovsek S, Gotlib J, Mesa RA, Vannucchi AM, Kiladjian JJ, Cervantes F, Harrison CN, Paquette R, Sun W, Naim A, Langmuir P, Dong T, Gopalakrishna P, Gupta V. Long-term survival in patients treated with ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis: COMFORT-I and -II pooled analyses. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, Levy RS, Gupta V, DiPersio JF, Catalano JV, Deininger M, Miller C, Silver RT, Talpaz M, Winton EF, Harvey JH Jr, Arcasoy MO, Hexner E, Lyons RM, Paquette R, Raza A, Vaddi K, Erickson-Viitanen S, Koumenis IL, Sun W, Sandor V, Kantarjian HM. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:799-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1559] [Cited by in RCA: 1620] [Article Influence: 124.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |