Published online May 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i15.2560

Revised: February 11, 2024

Accepted: April 8, 2024

Published online: May 26, 2024

Processing time: 143 Days and 18.4 Hours

Psychological assessment after intensive care unit (ICU) discharge is increasingly used to assess patients' cognitive and psychological well-being. However, few studies have examined those who recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). There is a paucity of data from the Middle East assessing the post-ICU discharge mental health status of patients who had COVID-19.

To evaluate anxiety and depression among patients who had severe COVID-19.

This is a prospective single-center follow-up questionnaire-based study of adults who were admitted to the ICU or under ICU consultation for > 24 h for COVID-19. Eligible patients were contacted via telephone. The patient’s anxiety and depression six months after ICU discharge were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The primary outcome was the mean HADS score. The secondary outcomes were risk factors of anxiety and/or depression.

Patients who were admitted to the ICU because of COVID-19 were screened (n = 518). Of these, 48 completed the questionnaires. The mean age was 56.3 ± 17.2 years. Thirty patients (62.5%) were male. The main comorbidities were endocrine (n = 24, 50%) and cardiovascular (n = 21, 43.8%) diseases. The mean overall HADS score for anxiety and depression at 6 months post-ICU discharge was 11.4 (SD ± 8.5). A HADS score of > 7 for anxiety and depression was detected in 15 patients (30%) and 18 patients (36%), respectively. Results from the multivariable ordered logistic regression demonstrated that vasopressor use was associated with the development of anxiety and depression [odds ratio (OR) 39.06, 95% confidence interval: 1.309–1165.8; P < 0.05].

Six months after ICU discharge, 30% of patients who had COVID-19 demonstrated a HADS score that confirmed anxiety and depression. To compare the psychological status of patients following an ICU admission (with vs without COVID-19), further studies are warranted.

Core Tip: The study describes the mental health status among critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) survivors. Long COVID can occur anytime 3-4 wk from the onset of COVID-19 symptoms. In our study, we followed up on the patients 6 months post-discharge. This study is the first to be conducted among Arabic populations in the Middle East using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, validated in the Arabic population. Public health stakeholders and practitioners need to understand some of the psychological consequences of COVID-19 infection, which could be used for future collaborative efforts to optimize patient care.

- Citation: Alhammad AM, Aldardeer NF, Alqahtani A, Aljawadi MH, Alnefaie B, Alonazi R, Almuqbil M, Alsaadon A, Alqahtani RM, Alballaa R, Alshehri B, Alarifi MI, Alosaimi FD. Mental health status among COVID-19 patients survivors of critical illness in Saudi Arabia: A 6-month follow-up questionnaire study. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(15): 2560-2567

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i15/2560.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i15.2560

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a novel viral disease involving mild-to-life-threatening respiratory illnesses[1]. The effects of “long COVID-19” have been widely reported. Post-acute COVID-19 (i.e., long COVID-19) is defined as symptoms that develop three or four weeks after the onset of initial COVID-19 symptoms. In some studies, cases with persistent symptoms beyond 12 wk have been referred to as “chronic COVID–19 syndrome”[2].

Patients who are critically ill from COVID-19 are at an increased risk of developing physical, cognitive, and psychological impairments[3]. Post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) is defined as any new or worsening physical, cognitive, or mental signs or symptoms following treatment in the intensive care unit (ICU). Anxiety and depression are two of the three main psychological components of PICS. The development of anxiety and depression three to 12 months after ICU discharge is not uncommon, affecting 46% and 29% of ICU patients, respectively[3]. In a Canadian population-based study of critically ill patients, the prevalence of mental disorders increased over 5 years after ICU discharge, from 41.5% (pre-hospitalization) to 55.6% (post-hospitalization)[4]. In a meta-analysis that included 28 studies, six studies examined the post-ICU psychological status of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, the authors reported that at least one-third of patients experienced psychological conditions including anxiety (30%) and depression (33%), six months post-recovery[5].

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a validated tool used to assess anxiety and depression in non-psychiatric hospitals. In calculating the HADS score, somatic symptoms of anxiety or depression, such as dizziness and fatigue, were excluded (to minimize confounding factors from physical diseases). Moreover, symptoms associated with serious psychiatric disorders were also excluded. Such symptoms are uncommon in medically ill populations[6]. The Arabic version of the HADS, validated in Arabic populations[7], is used with critically ill patients[8].

Results from a systematic review of patients with post-COVID-19 syndrome found that the frequency of depressive symptoms +12 wk after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection, ranged from 11% to 28%. Moreover, the frequency of clinically significant and/or severe depressive symptoms ranged from 3% to 12%. Furthermore, the review concluded that the severity of acute COVID-19 was not associated with the frequency of depressive symptoms[9]. A recent retrospective matched cohort study evaluated 236739 patients six months after illness. The study found a 46% increase in mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders among patients with COVID–19 patients compared to a matched cohort of patients with influenza[10]. Data from the Middle East assessing the mental health status of patients with COVID-19 after post-ICU discharge are lacking. Using a validated assessment tool, this study aimed to evaluate anxiety and depression among patients who had COVID-19 and identify the associated risk factors.

This prospective, single-center study was designed to assess the psychological status of patients with COVID-19, who were critically ill and admitted to the ICU. We screened all patients with laboratory or radiological confirmation of COVID-19, who were either admitted to the ICU or under ICU observation for > 24 h, between April 2020 and November 2020. Adults (≥ 18 years of age) were screened for eligibility. Patients eligible to participate in this study were contacted by telephone 6 months post-ICU discharge between October 2020 to May 2021. Those who consented completed a questionnaire that assessed their psychological status. Patients with language barriers and those who were unwilling to participate were excluded. Our study used the Arabic version of the HADS to evaluate anxiety and depression among patients with COVID-19 who were critically ill. The questionnaire was completed six months after ICU discharge. The HADS consists of 14 questions: Seven for screening anxiety symptoms and seven for signs of depression[11]. Each question was rated on a scale of 0–3 points. A score of 8 or greater on the anxiety or depression subscale represents clinically significant anxiety or depression[12]. Demographic data (age, sex, and weight), Glasgow Coma score, severity score [Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II)], ICU and hospital length of stay, comorbidities, and ICU care details including respiratory support and medications, such as corticosteroids, vasopressors, neuromuscular blocking agents, and tocilizumab, were extracted from the hospital system. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

The primary outcome was the mean HADS score six months after ICU discharge. Secondary outcomes were risk factors associated with anxiety and/or depression.

Continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations, while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. We categorized the patients based on the proportion meeting the predefined anxiety or depression threshold six months after ICU discharge. Of note, the authors of HADS suggested a 4-tier system (normal ≤ 7, mild 8-10, moderate 11-14, and severe 15-21) for considering severity[13]. We employed multivariable ordered logistic regression to analyze the factors associated with anxiety and/or depression. The data were analyzed using STATA 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, United States)[14].

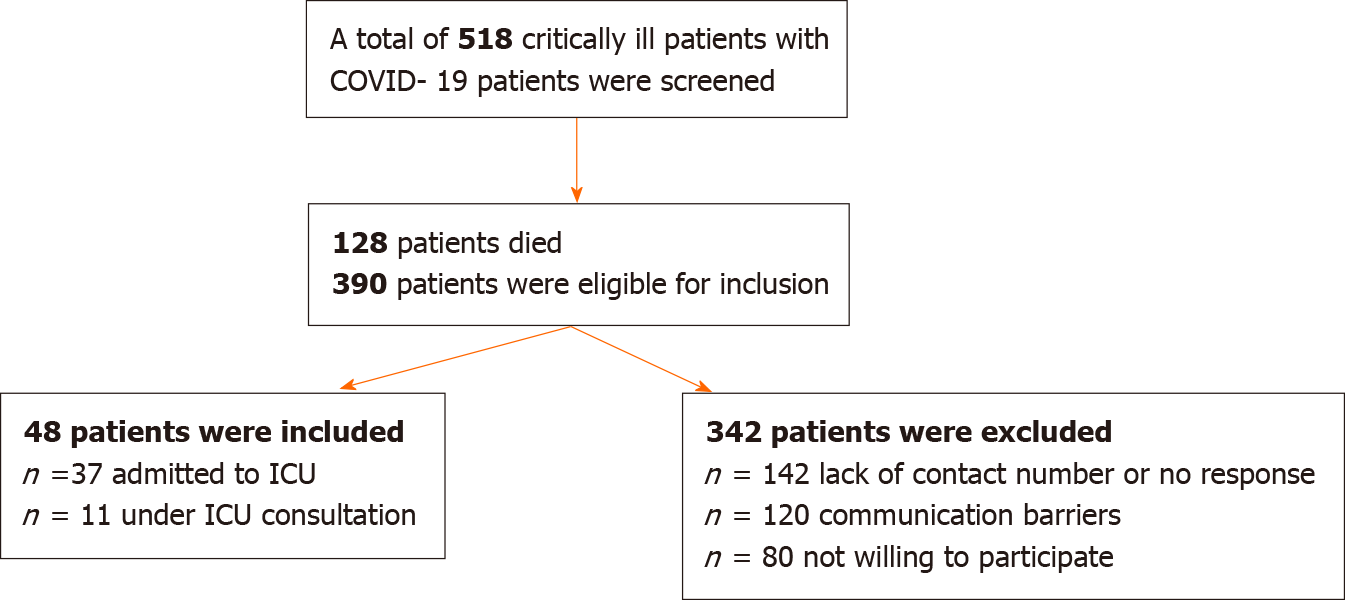

During the study period, 518 patients with COVID-19 admitted to the ICU were screened. Of the 390 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 48 completed the questionnaire (Figure 1). Most of the included patients were male 30 (62.5%). The mean age was 56.3 ± 17.2 years. The mean length of ICU stay was 9.1 ± 7.4 d. The main comorbidities were endocrine (n = 24, 50%) and cardiovascular (n = 21, 43.8 %) diseases (Table 1). The mean HADS score for anxiety and depression was 11.4 (SD ± 8.5). In this study, anxiety and depression (HADS score > 7) were detected in 15 (31.3%) and 18 (37.5%) of patients, respectively, six months after ICU discharge (Table 2). Importantly, results from the multivariate ordered logistic regression analysis demonstrated that vasopressor use was associated with the development of anxiety and depression [odds ratio (OR) 39.06, 95%CI: 1.309–1165.8; P < 0.05] (Table 3).

| Characteristics | n = 48 |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 56.3 ± 17.2 |

| Gender (male), n (%) | 30 (62.5) |

| Weight (kg), mean ± SD | 79.4 ± 20.4 |

| APACHE II score, mean ± SD | 12.4 ± 8.1 |

| ICU LOS, (days) mean ± SD | 9.1 ± 7.4 |

| Hospital LOS (days), mean ± SD | 23.1 ± 17.7 |

| Glasgow coma score, mean ± SD | 13.8 ± 3.3 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Endocrine diseases | 24 (50) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 21 (43.8) |

| Respiratory diseases | 5 (10.4) |

| Autoimmune/Inflammatory diseases | 3 (6.3) |

| Hematological diseases | 3 (6.3) |

| Renal diseases | 3 (6.3) |

| Neurological diseases | 2 (4.2) |

| Preexisting mental health problems | 2 (4.2) |

| Hepatic diseases | 1 (2.1) |

| ICU course n (%) | |

| Oxygen support | 23 (47.9) |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 6 (12.5) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 5 (10.4) |

| Corticosteroid | 27 (56.3) |

| Vasopressor | 7 (14.7) |

| Neuromuscular blocking agents | 2 (4) |

| Tocilizumab | 8 (16.3) |

| HADS cut-off scores, n (%) | Anxiety | Depression |

| Normal (≤ 7) | 33 (68.8) | 30 (62.5) |

| Mild (8-10) | 4 (8.3) | 13 (27) |

| Moderate (11-14) | 7 (14.5) | 3 (6.3) |

| Severe score (15-21) | 4 (8.3) | 2 (4.1) |

| Average score, mean ± SD | 5.81 ± 5.1 | 5.6 ± 4 |

| HADS average total score, mean ± SD | 11.4 ± 8.5 | |

| Variable | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value |

| Age | 1.007 (0.955–1.061) | NS |

| Gender | 1.294 (0.275–6.098) | NS |

| APACHEII | 0.919 (0.790–1.069) | NS |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 0.963 (0.206–4.496) | NS |

| Respiratory diseases | 0.084 (0.005–1.542) | NS |

| Endocrine diseases | 0.550 (0.123–2.453) | NS |

| Renal diseases | 0.165 (0.001–32.99) | NS |

| Autoimmune/Inflammatory diseases | 0.721 (0.040–12.95) | NS |

| Hematological diseases | 0.067 (0.001–8.979) | NS |

| Oxygen support | 6.119 (0.418–89.63) | NS |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 1.082 (0.025–46.40) | NS |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0.042 (0.0001–10.47) | NS |

| Corticosteroid use | 0.094 (0.006–1.420) | NS |

| Vasopressor use | 39.06 (1.309–1165.8) | < 0.05 |

| Tocilizumab use | 1.783 (0.215–14.81) | NS |

Our six-month follow-up questionnaire-based study found that at least one-third of patients under ICU care for COVID-19 experienced anxiety or depression following discharge. A recent retrospective study evaluated the six-month psychological outcomes of COVID-19 survivors and found that severe COVID-19 was associated with a higher incidence of mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorders than mild disease [hazard ratio (HR) 1.34, 95%CI: 1.24-1.46; P value < 0.0001][10]. In another recent study of 1617 patients, 23% had anxiety or depression at the 6-month follow-up (based on symptoms, exercise capacity, and quality of life). However, the same study found that only 4% of patients were admitted to the ICU[15]. Another single-center questionnaire study conducted in Saudi Arabia examined persistent symptoms 2 to 6 months post-COVID-19, regardless of severity. The results suggested that approximately half of the participants experienced persistent symptoms. Of these patients, 13% had anxiety and 10% had depression[16].

In this present study, we detected higher prevalences of anxiety and depression. This could be attributed to the increased severity of COVID-19, and the associated medical comorbidities, given the critical setting.

Inadequate brain perfusion and vasopressor-induced enhanced emotional memories may have contributed to the development of anxiety symptoms in our study[17]. One prospective cohort study examined 157 patients from general ICUs to explore the risk factors for psychological morbidity after three months of follow-up. It was shown that 44% of the participants were affected by anxiety, and the highest clinical risk factor for increased anxiety was the use of inotropes and vasopressors. However, no association has been observed between depression and vasopressor use[18]. This is consistent with our findings, which indicated that the need for vasopressors was associated with a higher HADS score.

Moreover, in our study, approximately 50% of patients required oxygen support, and approximately 25% required non-invasive and invasive mechanical ventilation. A prospective cohort study that evaluated patients with COVID-19 four months after discharge found that 26% and 18% of the 51 intubated patients, and 33.6% and 21.7% of the 126 patients who were not intubated, had symptoms of anxiety and depression, respectively[19].

The mean ICU length of stay in our study was 9.1 +/- 7.4 d. A prospective cohort study with a 5-year follow-up compared the physical outcomes between 276 patients with a prolonged ICU stay (≥ 8 d) and 398 patients with a short ICU stay. The study found that patients who required a long stay had significantly higher morbidity than those who had a short stay[20]. Additionally, a prospective cohort study of 46 patients with severe COVID-19 showed that depressive symptoms were more prominent in patients with physical impairment three months after ICU discharge[21].

To compare male and female long-term outcomes after intensive care for COVID-19 in terms of mortality, a prospective cohort study was conducted on 1722 male and 632 female ICU patients with COVID-19. The study found that males had poor long-term outcomes, with a 90–d mortality of 28.2% in males and 23.4% in females [22]. However, in terms of psychological symptoms, a single-center prospective cohort study investigated whether there was an association between the female sex and long-term COVID among 377 patients who were hospitalized due to COVID-19. The HADS was used for the anxiety and depression assessments. Overall, all psychological symptoms were significantly higher in females than males [anxiety symptoms 29.2% vs 12.9% (P = 0.001), depression symptoms 16.1% vs 7.5% (P = 0.009)][23]. Our results did not show any sex-related differences in the development of anxiety or depression. However, our finding could be attributed to the small sample size.

Our study has a few limitations. First, this was a single-center study with a small sample size, which may affect the generalizability of our findings. We screened many patients for eligibility, and more than 70% were excluded because of mortality, inability to reach the patient, or communication barriers. Second, a control group was lacking in our study. It would be of interest to compare anxiety and depression between patients with and without COVID-19 in future studies. Third, our study involved a single-point evaluation. We did not take differentiate psychological symptoms. Hence, for some patients, the symptoms may have previously existed, while for others, the symptoms may have been triggered during or after COVID-19. However, only two patients in our cohort had preexisting mental health diagnoses. Finally, using a screening scale to identify anxiety and depression may be less accurate than diagnostic interviews conducted by a specialized clinician. However, the HADS is a recognized validated instrument and is easier to implement in busy ICU settings.

Our study has the advantage of being conducted in the Middle East. We were able to evaluate anxiety and depression in patients who were critically ill with COVID-19. And investigate the associated risk factors. Additionally, the study covered a six-month follow-up period and used a validated questionnaire to evaluate depression and anxiety.

The long-term effects of COVID-19 affect many organ systems. This is a growing area of research as long COVID-19 can substantially affect the quality of life[2]. Ensuring the continuity of care for patients with COVID-19 beyond the acute phase of illness is crucial for addressing the long-term health consequences. To improve current clinical practice, post-acute care clinics or specialized follow-up programs for patients with long COVID-19 should be considered. These clinics would aim to provide comprehensive assessment of ongoing symptoms, monitor potential complications, and offer tailored treatment plans based on the needs of individual patients. Additionally, promoting multidisciplinary care that engages healthcare professionals from various specialties (e.g., pulmonology, cardiology, and psychology) can ensure holistic care for patients with diverse post-COVID-19 manifestations. Patient education is also paramount, as it can empower individuals to actively participate in their care, recognize signs of worsening symptoms through screening questionnaires, and adopt healthy lifestyle behaviors to promote recovery. Telemedicine and remote monitoring technologies can further facilitate continuity of care by enabling healthcare providers to remotely monitor patients' progress, provide timely interventions, and offer ongoing support, while overcoming access barriers[2,24]. Continuity of care for patients with COVID-19 beyond the acute illness, including psychological care, may assist in the early detection of anxiety and depression. Evidence suggests that initial and recurrent psychiatric illnesses occur between 14 and 19 d post-acute COVID-19[10]. Our study highlights the importance of psychological evaluation for patients who were discharged from the ICU following COVID-19 and the benefit of up to 6 months of follow-up to determine appropriate interventions. To verify our findings, further studies comparing the psychological status of patients with and without COVID-19 are warranted.

Patients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 were anxious or depressed up to six months post-ICU discharge. To compare the psychological status of patients with or without COVID-19, further investigations are warranted.

The authors thank the Researchers Supporting Project number, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, No. RSPD2024R919.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Saudi Society of Clinical Pharmacy, 20212715; Saudi Critical Care Society, 202113661.

Specialty type: Critical care medicine

Country/Territory of origin: Saudi Arabia

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Tang H, China S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Wang C, Zhao H. The Impact of COVID-19 on Anxiety in Chinese University Students. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 46.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, Cook JR, Nordvig AS, Shalev D, Sehrawat TS, Ahluwalia N, Bikdeli B, Dietz D, Der-Nigoghossian C, Liyanage-Don N, Rosner GF, Bernstein EJ, Mohan S, Beckley AA, Seres DS, Choueiri TK, Uriel N, Ausiello JC, Accili D, Freedberg DE, Baldwin M, Schwartz A, Brodie D, Garcia CK, Elkind MSV, Connors JM, Bilezikian JP, Landry DW, Wan EY. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3262] [Cited by in RCA: 3001] [Article Influence: 750.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hatch R, Young D, Barber V, Griffiths J, Harrison DA, Watkinson P. Anxiety, Depression and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder after critical illness: a UK-wide prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2018;22:310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 42.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Olafson K, Marrie RA, Bolton JM, Bernstein CN, Bienvenu OJ, Kredentser MS, Logsetty S, Chateau D, Nie Y, Blouw M, Afifi TO, Stein MB, Leslie WD, Katz LY, Mota N, El-Gabalawy R, Enns MW, Leong C, Sweatman S, Sareen J. The 5-year pre- and post-hospitalization treated prevalence of mental disorders and psychotropic medication use in critically ill patients: a Canadian population-based study. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:1450-1461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ahmed H, Patel K, Greenwood DC, Halpin S, Lewthwaite P, Salawu A, Eyre L, Breen A, O'Connor R, Jones A, Sivan M. Long-term clinical outcomes in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus outbreaks after hospitalisation or ICU admission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med. 2020;52:jrm00063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 47.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:69-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6329] [Cited by in RCA: 7237] [Article Influence: 314.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Terkawi AS, Tsang S, AlKahtani GJ, Al-Mousa SH, Al Musaed S, AlZoraigi US, Alasfar EM, Doais KS, Abdulrahman A, Altirkawi KA. Development and validation of Arabic version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Saudi J Anaesth. 2017;11:S11-S18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shdaifat SA, Al Qadire M. Anxiety and depression among patients admitted to intensive care. Nurs Crit Care. 2022;27:106-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Renaud-Charest O, Lui LMW, Eskander S, Ceban F, Ho R, Di Vincenzo JD, Rosenblat JD, Lee Y, Subramaniapillai M, McIntyre RS. Onset and frequency of depression in post-COVID-19 syndrome: A systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;144:129-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, Luciano S, Harrison PJ. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:416-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 901] [Cited by in RCA: 1295] [Article Influence: 323.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hatch R, Young D, Barber V, Harrison DA, Watkinson P. The effect of postal questionnaire burden on response rate and answer patterns following admission to intensive care: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mikkelsen ME, Still M, Anderson BJ, Bienvenu OJ, Brodsky MB, Brummel N, Butcher B, Clay AS, Felt H, Ferrante LE, Haines KJ, Harhay MO, Hope AA, Hopkins RO, Hosey M, Hough CTL, Jackson JC, Johnson A, Khan B, Lone NI, MacTavish P, McPeake J, Montgomery-Yates A, Needham DM, Netzer G, Schorr C, Skidmore B, Stollings JL, Umberger R, Andrews A, Iwashyna TJ, Sevin CM. Society of Critical Care Medicine's International Consensus Conference on Prediction and Identification of Long-Term Impairments After Critical Illness. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:1670-1679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 64.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Snaith RP, Zigmond AS. The hospital Anxiey and depression scale with the irritability-depression-anxiety scale and the Leeds situational anxiety scale: manual. Windsor, UK: NFER-NELSON, 1994. |

| 14. | StataCorp. Stata statistical software. Release 17. TX: StataCorp LP, College Station. StataCrop LLC, 2021. |

| 15. | Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X, Kang L, Guo L, Liu M, Zhou X, Luo J, Huang Z, Tu S, Zhao Y, Chen L, Xu D, Li Y, Li C, Peng L, Xie W, Cui D, Shang L, Fan G, Xu J, Wang G, Zhong J, Wang C, Wang J, Zhang D, Cao B. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3187] [Cited by in RCA: 2890] [Article Influence: 722.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Garout MA, Saleh SAK, Adly HM, Abdulkhaliq AA, Khafagy AA, Abdeltawab MR, Rabaan AA, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Al-Tawfiq JA, Alandiyjany MN. Post-COVID-19 syndrome: assessment of short- and long-term post-recovery symptoms in recovered cases in Saudi Arabia. Infection. 2022;50:1431-1439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | VanValkinburgh D, Kerndt CC, Hashmi MF. Inotropes and vasopressors. Signa Vitae 2023 Feb 19 [Cited 2023 Jul 4]; 13: 46-52. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482411/. |

| 18. | Wade DM, Howell DC, Weinman JA, Hardy RJ, Mythen MG, Brewin CR, Borja-Boluda S, Matejowsky CF, Raine RA. Investigating risk factors for psychological morbidity three months after intensive care: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2012;16:R192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Writing Committee for the COMEBAC Study Group; Morin L, Savale L, Pham T, Colle R, Figueiredo S, Harrois A, Gasnier M, Lecoq AL, Meyrignac O, Noel N, Baudry E, Bellin MF, Beurnier A, Choucha W, Corruble E, Dortet L, Hardy-Leger I, Radiguer F, Sportouch S, Verny C, Wyplosz B, Zaidan M, Becquemont L, Montani D, Monnet X. Four-Month Clinical Status of a Cohort of Patients After Hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325:1525-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 402] [Article Influence: 100.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hermans G, Van Aerde N, Meersseman P, Van Mechelen H, Debaveye Y, Wilmer A, Gunst J, Casaer MP, Dubois J, Wouters P, Gosselink R, Van den Berghe G. Five-year mortality and morbidity impact of prolonged vs brief ICU stay: a propensity score matched cohort study. Thorax. 2019;74:1037-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | van Gassel RJJ, Bels J, Remij L, van Bussel BCT, Posthuma R, Gietema HA, Verbunt J, van der Horst ICC, Olde Damink SWM, van Santen S, van de Poll MCG. Functional Outcomes and Their Association With Physical Performance in Mechanically Ventilated Coronavirus Disease 2019 Survivors at 3 Months Following Hospital Discharge: A Cohort Study. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:1726-1738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zettersten E, Engerström L, Bell M, Jäderling G, Mårtensson J, Block L, Larsson E. Long-term outcome after intensive care for COVID-19: differences between men and women-a nationwide cohort study. Crit Care. 2021;25:86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bai F, Tomasoni D, Falcinella C, Barbanotti D, Castoldi R, Mulè G, Augello M, Mondatore D, Allegrini M, Cona A, Tesoro D, Tagliaferri G, Viganò O, Suardi E, Tincati C, Beringheli T, Varisco B, Battistini CL, Piscopo K, Vegni E, Tavelli A, Terzoni S, Marchetti G, Monforte AD. Female gender is associated with long COVID syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28:611.e9-611.e16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 89.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Schmidt K, Gensichen J, Gehrke-Beck S, Kosilek RP, Kühne F, Heintze C, Baldwin LM, Needham DM. Management of COVID-19 ICU-survivors in primary care: - a narrative review. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22:160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |