Published online May 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i15.2475

Revised: April 5, 2024

Accepted: April 23, 2024

Published online: May 26, 2024

Processing time: 120 Days and 22.3 Hours

Total knee replacement, a common surgery among the elderly primarily nece

Core Tip: The multimodal rehabilitation approach for elderly patients undergoing knee replacement surgery integrates various facets of postoperative care, including tailored physical therapy, advanced pain management techniques, and lifestyle adjustments. Emphasizing the need for personalized treatment plans, the article sheds light on the importance of exercises for reducing inflammation and enhancing mobility, alongside innovative pain management strategies like nerve block devices and non-narcotic medications. It underscores the necessity of continuous monitoring and adaptation of the rehabilitation plan, highlighting its impact on accelerating recovery and improving the quality of life for elderly knee replacement patients.

- Citation: Nashwan AJ. Optimizing pain management in elderly patients post-knee surgery: A novel collaborative strategy. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(15): 2475-2478

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i15/2475.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i15.2475

Rehabilitation care for pain in elderly knee replacement patients is a critical aspect of postoperative care that aims to improve the quality of life and expedite recovery. Total knee replacement, often necessitated by conditions like osteoarthritis, involves replacing the damaged knee joint with an artificial one[1]. This surgery is increasingly common among the elderly, with over 600000 procedures performed annually, and these artificial joints typically last for at least 15 years[2].

Postoperative rehabilitation is crucial for successful recovery. In the initial weeks after surgery, outpatient physical therapy is recommended[3]. Exercises are designed to reduce inflammation, increase mobility, and strengthen supporting leg muscles, facilitating improved knee bending[4]. Typical exercises include quadriceps sets, straight leg lifts, ankle pumps, and seated knee bends[4]. Patients are generally encouraged to walk as much as comfortably possible, often starting with the aid of a walker or cane and progressing to independent walking around 3 wk post-surgery[5].

Pain management is another essential component of postoperative care. Knee surgery can be pretty painful, and managing this pain effectively is vital for a successful recovery[6]. While narcotics are often used, they are not considered the most effective for pain relief[7]. A more multimodal approach to pain management is often employed, including using nerve block devices that reduce the need for medication in the first week after surgery[7].

The recovery timeline for elderly patients undergoing knee replacement is typically around 12 wk[8]. This period includes significant improvement in swelling reduction and movement ability within the first four to 6 wk[8]. The following weeks focus on increasing the range of motion and building muscles around the new joint[8]. Adherence to physical therapist and doctor recommendations is crucial for effective recovery without overexerting the patient, which could otherwise delay healing.

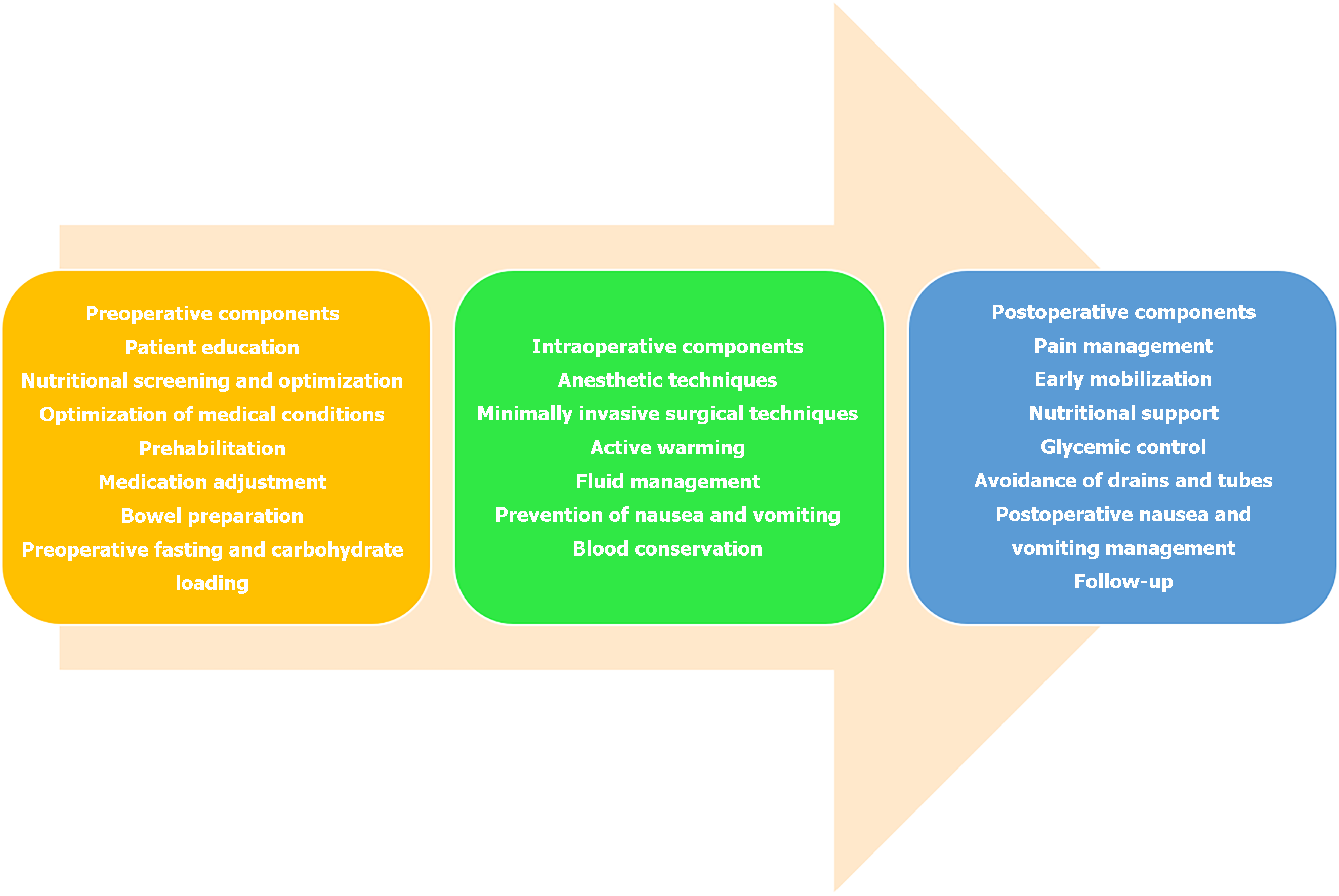

Interestingly, the field of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) has witnessed significant advances in recent years, focusing on minimizing surgical stress, optimizing physiological function, and facilitating a faster recovery for patients[9]. One of the notable developments is the integration of digital health technologies, such as telehealth and mobile health applications, which enable real-time monitoring of patient progress and symptoms, thus allowing for personalized adjustments to care plans[10]. Additionally, there's a growing emphasis on multimodal pain management strategies that incorporate regional anesthesia and non-opioid medications, reducing the reliance on opioids and their associated risks[11]. Research into the gut microbiome's role in recovery and the impact of prehabilitation-physical and nutritional preparation before surgery—promises to further refine ERAS protocols[12]. These advancements, combined with a multidisciplinary approach that includes patients in decision-making, signify a shift towards a more holistic, patient-centered care model in surgical recovery (Figure 1). Liu et al[13] present a retrospective study evaluating the effectiveness of programmed pain nursing combined with collaborative nursing in elderly patients undergoing knee replacement surgery[13]. It includes an analysis of 116 patients divided into two groups: A control group receiving standard nursing care and an observation group receiving both programmed and collaborative nursing. The study finds that the observation group demonstrated better functional outcomes, including higher activities of daily living (ADL) scores and better knee joint function scores at 2 and 3 months post-discharge, compared to the control group. The study concludes that programmed pain nursing and collaborative nursing can significantly improve patient outcomes regarding pain reduction and enhanced rehabilitation post-knee replacement surgery.

The study's retrospective design is a crucial element to consider. In retrospective studies, researchers analyze existing data to find correlations and patterns. However, this design inherently limits the ability to establish causality firmly. The lack of randomization and control groups means that other variables could influence the outcomes, making it challenging to attribute improvements to specific nursing interventions directly. A randomized controlled trial (RCT), where patients are randomly assigned to different treatment groups, would provide more robust evidence. RCTs are considered the gold standard in clinical research because they minimize bias and allow for a more straightforward interpretation of the effectiveness of an intervention.

The study's sample size, comprising 116 patients, is adequate for initial explorations but might not capture the diversity and complexity of the broader population undergoing knee replacement surgery. Elderly patients can have varying health statuses, comorbidities, and personal circumstances, all of which can influence their recovery. A more extensive and more diverse sample would provide a more representative picture of the population and strengthen the reliability of the findings.

Another consideration is the study's reliance on subjective measures, such as ADL and Visual Analog Scale scores. While valuable for capturing patients' self-reported experiences, these measures are influenced by individual perceptions and biases. Objective measures, alongside these subjective assessments, could provide a more comprehensive under

The follow-up duration of three months post-discharge is relatively short. Knee replacement is a major surgery, and its long-term effects can be significant. A more extended follow-up period would allow researchers to observe the sustained impacts of the nursing interventions on patients' recovery, functionality, and overall quality of life. This could be particularly relevant for understanding chronic pain management and long-term mobility.

Furthermore, nutrition plays a critical role in patient recovery, especially after major surgeries like knee replacement[14]. A well-structured nutritional plan can aid in faster wound healing, reduce the risk of infections, and support the overall recovery process[15]. Discussing nutritional strategies within the context of perioperative care could provide insights into optimizing patient outcomes.

Finally, the generalizability of the study's findings is a crucial concern. Since the survey is conducted within a specific patient population and healthcare setting, its results may not be applicable to other settings or populations. Factors like healthcare infrastructure, patient demographics, and cultural differences can influence the outcomes of such interventions. Thus, caution should be exercised in extrapolating these findings to other groups without further research[16].

The study offers valuable insights into postoperative care for elderly knee replacement patients, highlighting the potential benefits of integrating programmed pain nursing with collaborative nursing. While the findings suggest positive outcomes, the study's limitations, such as its retrospective design and limited follow-up duration, necessitate further research. Nonetheless, it contributes meaningfully to the field of geriatric orthopedic nursing, proposing a novel approach to pain management and rehabilitation in this vulnerable patient group.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Qatar

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade C

P-Reviewer: Yang RS, Taiwan S-Editor: Liu H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Primorac D, Molnar V, Rod E, Jeleč Ž, Čukelj F, Matišić V, Vrdoljak T, Hudetz D, Hajsok H, Borić I. Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review of Pathogenesis and State-Of-The-Art Non-Operative Therapeutic Considerations. Genes (Basel). 2020;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Arshi A, Hughes AJ, Robin JX, Parvizi J, Fillingham YA. Return to Sport After Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: Counseling the Patient on Resuming an Active Lifestyle. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2023;16:329-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wainwright TW, Burgess L. Early Ambulation and Physiotherapy After Surgery. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery. 2020.. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Raposo F, Ramos M, Lúcia Cruz A. Effects of exercise on knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Musculoskeletal Care. 2021;19:399-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Matranga E. Acute care physical therapy for a patient following left total hip arthroplasty. 2021, California State University, Sacramento. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/10211.3/218623. |

| 6. | Keast M, Hutchinson AF, Khaw D, McDonall J. Impact of Pain on Postoperative Recovery and Participation in Care Following Knee Arthroplasty Surgery: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Pain Manag Nurs. 2022;23:541-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Laigaard J, Pedersen C, Rønsbo TN, Mathiesen O, Karlsen APH. Minimal clinically important differences in randomised clinical trials on pain management after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:1029-1037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 53.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wainwright TW, Gill M, McDonald DA, Middleton RG, Reed M, Sahota O, Yates P, Ljungqvist O. Consensus statement for perioperative care in total hip replacement and total knee replacement surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS(®)) Society recommendations. Acta Orthop. 2020;91:3-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 425] [Article Influence: 85.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Carli F. Physiologic considerations of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) programs: implications of the stress response. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62:110-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gillis C, Ljungqvist O, Carli F. Prehabilitation, enhanced recovery after surgery, or both? A narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128:434-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 42.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wardhan R, Chelly J. Recent advances in acute pain management: understanding the mechanisms of acute pain, the prescription of opioids, and the role of multimodal pain therapy. F1000Res. 2017;6:2065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sibley D, Chen M, West MA, Matthew AG, Santa Mina D, Randall I. Potential mechanisms of multimodal prehabilitation effects on surgical complications: a narrative review. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2023;48:639-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu L, Guan QZ, Wang LF. Rehabilitation care for pain in elderly knee replacement patients. World J Clin Cases. 2024;12:721-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 14. | Smith-Ryan AE, Hirsch KR, Saylor HE, Gould LM, Blue MNM. Nutritional Considerations and Strategies to Facilitate Injury Recovery and Rehabilitation. J Athl Train. 2020;55:918-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Buckthorpe M, Gokeler A, Herrington L, Hughes M, Grassi A, Wadey R, Patterson S, Compagnin A, La Rosa G, Della Villa F. Optimising the Early-Stage Rehabilitation Process Post-ACL Reconstruction. Sports Med. 2024;54:49-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Soffin EM, YaDeau JT. Enhanced recovery after surgery for primary hip and knee arthroplasty: a review of the evidence. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117:iii62-iii72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |