Published online Apr 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i10.1778

Peer-review started: November 2, 2023

First decision: January 15, 2024

Revised: February 3, 2024

Accepted: March 5, 2024

Article in press: March 5, 2024

Published online: April 6, 2024

Processing time: 152 Days and 3.8 Hours

Rectocutaneous fistulae are common. The infection originates within the anal glands and subsequently extends into adjacent regions, ultimately resulting in fistula development. Cellular angiofibroma (CAF), also known as an angiomyofibroblastoma-like tumor, is a rare benign soft tissue neoplasm predominantly observed in the scrotum, perineum, and inguinal area in males and in the vulva in females. We describe the first documented case CAF that developed within a rectocutaneous fistula and manifested as a perineal mass.

In the outpatient setting, a 52-year-old male patient presented with a 2-year history of a growing perineal mass, accompanied by throbbing pain and minor scrotal abrasion. Physical examination revealed a soft, well-defined, non-tender mass at the left buttock that extended towards the perineum, without a visible opening. The initial assessment identified a soft tissue tumor, and the laboratory data were within normal ranges. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) revealed swelling of the abscess cavity that was linked to a rectal cutaneous fistula, with a track-like lesion measuring 6 cm × 0.7 cm in the left perineal region and attached to the left rectum. Rectoscope examination found no significant inner orifices. A left medial gluteal incision revealed a thick-walled mass, which was excised along with the extending tract, and curettage was performed. Histopathological examination confirmed CAF diagnosis. The patient achieved total resolution during follow-up assessments and did not require additional hospitalization.

CT imaging supports perineal lesion diagnosis and management. Perineal angiofibromas, even with a cutaneous fistula, can be excised transperineally.

Core Tip: Although uncommon, certain typical clinical conditions, such as rectal cutaneous fistulas, may manifest in complex presentations, as demonstrated in this patient. Notably, recurrence and complications such as incontinence are frequently associated with complex fistulas and incomplete mapping. Therefore, establishing a definitive diagnosis through a precise mapping of the fistula is imperative before surgical intervention. Computed tomography imaging is useful for detecting, understanding and managing perineal lesions. Perineal angiofibromas can be removed via transperineal excision, even if linked to a rectal cutaneous fistula. In such complex cases, a personalized and careful diagnostic approach is crucial.

- Citation: Chen HE, Lu YY, Su RY, Wang HH, Chen CY, Hu JM, Kang JC, Lin KH, Pu TW. Cellular angiofibroma arising from the rectocutaneous fistula in an adult: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(10): 1778-1784

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i10/1778.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i10.1778

Cellular angiofibroma (CAF), also known as an angiomyofibroblastoma (AMF)-like tumor, is a rare benign soft tissue neoplasm that is predominantly observed in the scrotum, perineum, and inguinal area in males and the vulva in females. This description was first published by Nucci et al[1] in 1997. Microscopically, CAFs are distinguished by small- to medium-sized vessels with hyaline fibrosis and bland spindle cells[2]. The diagnosis of CAF can be challenging, particularly in cases outside the genital region, where more common pathologies may initially take precedence. Furthermore, its pathological attributes are similar to those of other mesenchymal tumors. Thus, immunohistochemistry is instrumental in separating CAF from other mesenchymal tumors, including those with the potential for higher aggressiveness[3,4].

Precise diagnosis of perianal fistulas poses an ongoing difficulty for medical professionals. Most often, perianal abscesses begin with an infection of the anal gland. Obstructing these glands can result in stagnation, excessive bacterial growth, and abscess formation within the intersphincteric groove[5]. Multiple drainage pathways exist for these abscesses, the most typical of which involve either downward extension into the anoderm or lateral progression involving the external sphincter muscle and extending into the ischiorectal fossa. Less prevalent dissemination patterns include expansion into the supralevator space and advancement within the submucosal plane. After abscess drainage, whether through surgical intervention or spontaneous resolution, there is the potential for septic foci to persist, and the draining tract may undergo epithelialization, giving rise to the development of a chronic anorectal fistula. Approximately 60% of abscesses eventually result in the formation of a fistula[6].

To date, no description of a CAF derived from a rectal-cutaneous fistula has been reported. Here, we describe the case of a 52-year-old man with a CAF that arose from a rectocutaneous fistulous tract that extended to the perineal region.

A perineal mass, present for 2 years, that had gradually increased in size over time, causing discomfort.

A 52-year-old Asian man visited the outpatient department for discomfort associated with a perineal mass that he had first noticed 2 years prior. Initially, the patient experienced pain but did not seek medical assistance because the recurrent condition had a negligible impact on his daily routine. However, the swelling gradually increased, leading to throbbing pain and minor scrotal abrasion.

The patient had a medical history of hypertension and dyslipidemia, which were managed with oral medication. He also had a surgical history of ureteroscopic lithotripsy 4 years prior and conventional hemorrhoidectomy 10 years prior. The patient’s medical history revealed no evidence of underlying abdominal malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, abdominal trauma, or other gastrointestinal disorders.

No family history of abdominal neoplasms or inflammatory bowel disease was noted, and the patient exhibited regular social functioning and self-care abilities.

Vital signs, including blood pressure and body temperature, were within the normal ranges. Physical examination revealed a soft, well-defined, non-tender mass at the left buttock tracking towards the patient’s perineum, without a visible opening. The preliminary diagnosis indicated a soft tissue tumor.

Laboratory data, including white blood cell count, hemoglobin, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and electrolytes such as so

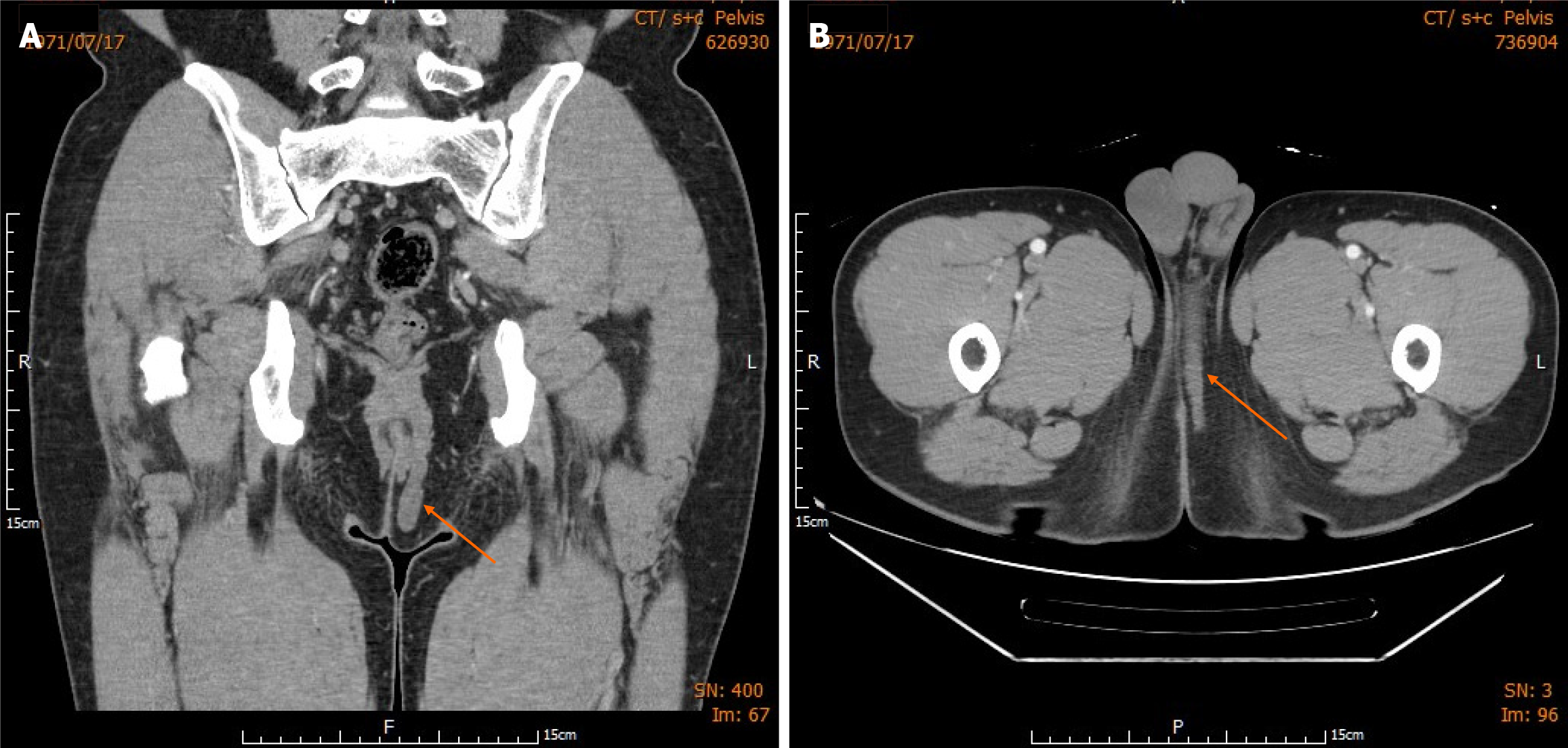

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a swelling of the abscess cavity connected to a rectal cutaneous fistula. A track-like lesion (approximately 6 cm × 0.7 cm) was observed between the internal and external anal sphincters (Figure 1A). The superior aspect of the lesion was positioned within the intersphincteric plane, and the lower part extended into the perineum (Figure 1B). There was no evidence of invasion of the levator ani muscle or muscular plane of the gluteus, and the small intestine and mesentery appeared normal.

The definitive diagnosis was CAF.

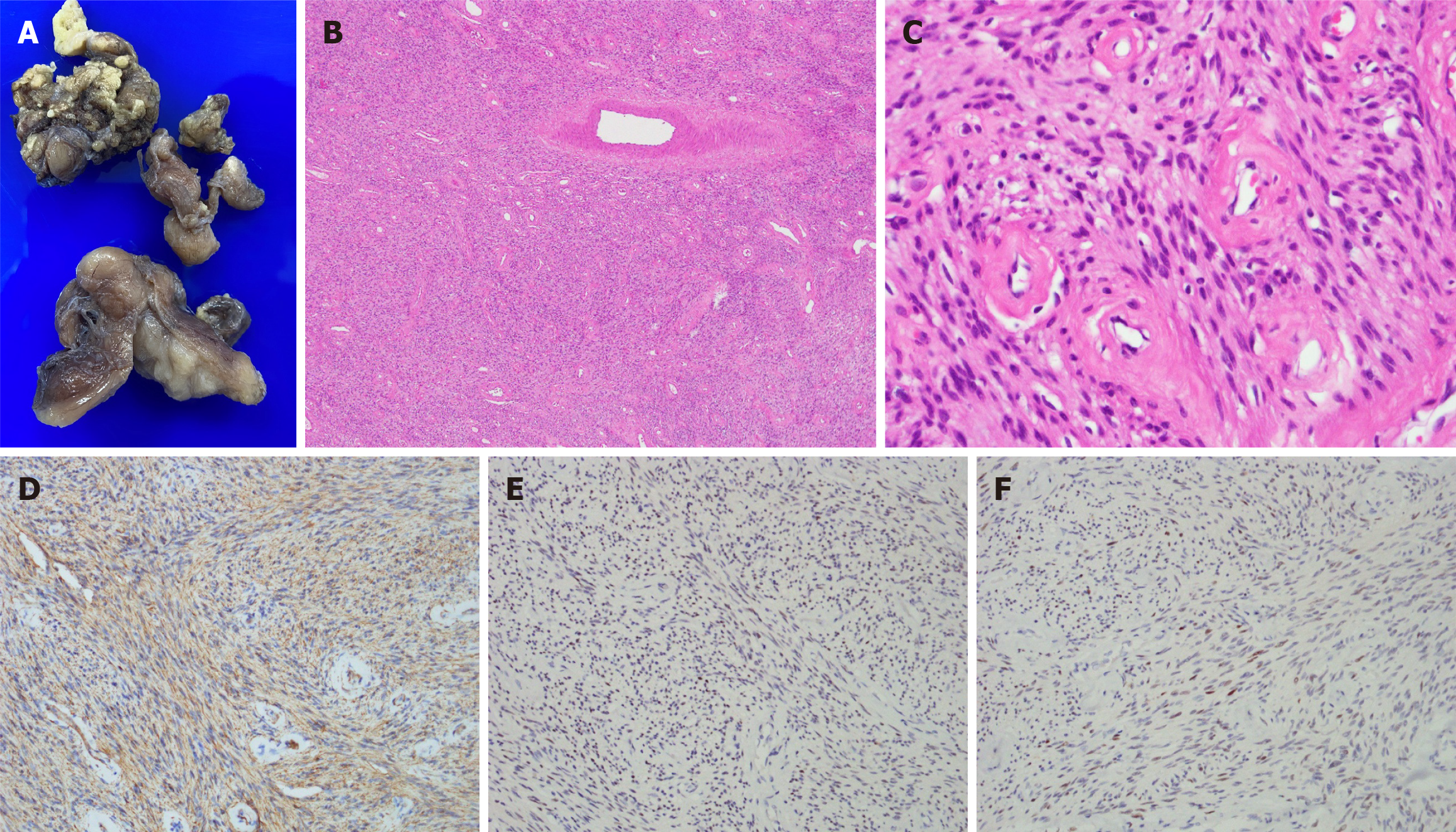

After bowel preparation using an enema, the patient was transferred to the operating room and placed in the prone position under epidural anesthesia. A protruding mass was identified at the 1 o’clock position. An incision was made via the left medial gluteal approach, and a thick-walled mass was encountered (Figure 2A). The mass was excised, and the identified tract was found to extend medially. The lesion was found to be 5.4 cm × 3.2 cm × 1.8 cm in size, well circumscribed, and connected to a track-like tissue (Figure 2B). The tract was assessed via digital examination, and no apparent link to the rectum was identified. The tract was then partially excised and curetted, and the skin was closed over a Penrose drain (Figure 2C). Histopathological examination of the specimen confirmed findings consistent with CAF. Grossly, the specimens were gray and elastic (Figure 3). Microscopically, the section showed tumors with well-circumscribed borders that were primarily composed of consistently uniform, short, and spindle-shaped cells within a fibrous stroma. The stroma was characterized by the presence of short bundles of delicate collagen fibers and numerous small-to medium-sized thick-walled vessels with hyaline and fibrotic vascular walls. The spindle cell component was moderately-to-highly cellular and was randomly distributed throughout the lesion, occasionally in a fascicular arrangement. The tumor cells were immunohistochemically positive for smooth muscle actin, focally positive for estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor, and negative for S100, cluster of differentiation 34, and desmin.

The patient had no complications postoperatively and was discharged on the 1st postoperative day. He was instructed to continue with routine dressings during the upcoming period, and throughout the 6-mo follow-up period, complete resolution of the fistulous tract was observed. The patient expressed satisfaction with the treatment outcome and no further hospitalization was necessary.

We describe the first documented case of a CAF arising from a rectocutaneous fistula that presented as a perineal mass. CAFs are benign mesenchymal tumors that feature spindle cells and conspicuous stromal blood vessels. This condition most frequently occurs in the inguinoscrotal or vulvovaginal regions, and the tumors exhibit the highest frequency in women during the fifth decade of life, whereas men are typically affected in their seventh decade[7]. The differential diagnosis of this neoplasm is broad and encompasses epithelioid leiomyoma, CAF, aggressive angiomyxoma, and AMF. In a series of 51 patients, extragenital CAF was discovered in locations that include the vulva-vagina, inguinal-scrota, retroperitoneum, and urethra, and the rectal-cutaneous fistula stie has not been reported previously[8]. In our study, the unusual tumor site posed considerable diagnostic challenges during the preoperative evaluation and management of the patient.

The presence of a rectal cutaneous fistula reflects the chronic state of an ongoing perianal infection. It commonly presents as a granulating channel that develops between the anorectal and perianal regions or perineum. The onset of most fistulas is attributed to anorectal abscesses, and fistula development often occurs when an abscess drains spontaneously. Anal fistulas are predominantly caused by infected anal glands in more than 90% of patients that create pathways for the infection to traverse the anal lumen into the deep sphincter muscles, leading to chronic continuous perianal infection. The infection can gain access to the wall of the anal canal by passing through a fissure or another type of wound. Once established, fecal content usually maintains the patency of the infected tract[9]. A typical fistula comprises a passageway with both a primary (internal) entrance and a secondary (external) exit.

Rectal cutaneous fistulas are characterized by the continuous or sporadic release of purulent, mucous, or bloody dis

Radiologists have introduced the following alternative grading system for evaluating the outcomes of anorectal fistulae, known as the St. James's University Hospital classification, which incorporates axial plane landmarks, abscesses, and secondary extensions: 0, normal appearance; 1, simple linear intersphincteric fistula; 2, intersphincteric fistula with intersphincteric abscess or secondary fistulous tract; 3, trans-sphincteric fistula; 4, trans-sphincteric fistula with abscess or secondary track within the ischioanal or ischiorectal fossa; and 5, supralevator and translevator disease. Grades 1 and 2 typically lead to favorable outcomes, whereas less favorable results are commonly associated with grades 3–5, which often necessitates reoperation due to recurrence[12,13].

Our patient had experienced a perianal mass for a duration of 2 years before seeking medical attention, indicating that the formation of the fistulous tract and abscess likely predated this timeframe. Despite the resolution of the abscess, the fistulous tract remained intact. Most likely, the CAF emerged over time within the previous abscess cavity, with the internal entry of the fistulous tract positioned in the anal canal. The pathogenesis of rectal cutaneous fistulae is well established; however, the origin of the CAFs remains unclear. Several hypotheses have been proposed, including the possibility of monoallelic deletion of retinoblastoma 1 and forkhead box 1, both of which are located on chromosome 13q14, a region strongly implicated in disease pathogenesis[14]. As for the potential reasons behind CAF growth within a rectocutaneous fistula, we postulate that the presence of this benign mesenchymal tumor in such a specific anatomical location may be attributed to the chronic inflammation associated with the fistulous tract. Chronic inflammation is known to create a microenvironment that is conducive to tumorigenesis and promote cellular changes and the development of neoplastic lesions[14]. Further research is needed to elucidate the precise mechanisms that link chronic inflammation, rectocutaneous fistula, and CAF development.

In the present case, the initial impression on physical examination was a soft tissue mass over the perineum. A rectal-cutaneous fistula was not diagnosed until CT was performed, and CT is often performed as a first-line examination to locate the perineal mass and define its anatomical relationship[15]. In addition to CT, endosonography and MRI can serve as diagnostic tools for perianal tumors and rectal cutaneous fistulas[16]. In the present case, the path of the fistulous tract within the perianal region was identified on the left side, traversed the intersphincteric area, and extended inferiorly into the perineum. Considering that the tract was a rectal-cutaneous fistula accompanied by a soft tissue tumor, total excision of the mass with marsupialization was performed. Surgery was initiated through a transperineal incision and tumor excision was performed without compromising rectal integrity. The procedure was performed successfully using a minimally invasive technique that aimed to achieve permanent closure of the fistula tract without functional impairment. While the surgeon may consider flatus incontinence a minor issue, it can be a profound embarrassment for the patient[12].

Here, we present the case of a patient who was diagnosed with the coexistence of a perianal fistula and CAF, with clear margins observed after surgical resection. Notably, CAFs are generally characterized by a benign clinical course and exhibit a minimal risk of recurrence at the resection site. Local excision with negative margins is the current standard treatment[17]. It necessitates careful consideration of CAF’s growth location, thereby tailoring the surgical approach to the specific anatomical site involved. In the context of a retrospective study of patients with a vulvovaginal CAF[18], urinary catheterization was employed during the excision procedure to ensure the safety of the patients and prevent urethral injury. When dealing with CAF growth within a rectocutaneous fistula, unlike vulvovaginal CAF, it is imperative to utilize pre-operative imaging examinations and intraoperative physical examination to ensure the preservation of the sphincter muscles when ligating the fistula tract. In our study, the tract was completely resected, with no noted impairment of the sphincter function in the postoperative course.

Although uncommon, certain typical clinical conditions, such as rectal cutaneous fistulas, can appear in complex ways, as in the case presented here. Before surgery, it is essential to confirm the diagnosis and outline the fistula accurately. Complex fistulae and incomplete mapping often result in recurrence or incontinence. CT imaging is useful for spotting and understanding perineal lesions and aiding treatment planning. Perineal angiofibromas can be removed via transperineal excision, even if they are linked to a rectal cutaneous fistula. The findings of our study indicates that, for complex cases like this one, a personalized approach and careful diagnostic setup are crucial. The accumulation of similar cases and larger-scale studies may help identify the best treatment approach.

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of the people at the Department of Surgery, Tri-Service General Hospital, Songshan Branch. This report would not have been possible without their efforts in data collection and inter-professional collaboration in treating this patient.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Han J, China; Zhang HZ, China; Zheng L, China S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Nucci MR, Granter SR, Fletcher CD. Cellular angiofibroma: a benign neoplasm distinct from angiomyofibroblastoma and spindle cell lipoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:636-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Iwasa Y, Fletcher CDM, Flucke U. Cellular angiofibroma. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Soft tissue and bone tumours. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. (WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed.; vol. 3). |

| 3. | Hashino Y, Nishio J, Maeyama A, Aoki M, Nabeshima K, Yamamoto T. Intra-articular angiofibroma of soft tissue of the knee: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;7:229-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhao M, Sun K, Li C, Zheng J, Yu J, Jin J, Xia W. Angiofibroma of soft tissue: clinicopathologic study of 2 cases of a recently characterized benign soft tissue tumor. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:2208-2215. [PubMed] |

| 5. | PARKS AG. Pathogenesis and treatment of fistuila-in-ano. Br Med J. 1961;1:463-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Robinson AM Jr, DeNobile JW. Anorectal abscess and fistula-in-ano. J Natl Med Assoc. 1988;80:1209-1213. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Mandato VD, Santagni S, Cavazza A, Aguzzoli L, Abrate M, La Sala GB. Cellular angiofibroma in women: a review of the literature. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Iwasa Y, Fletcher CD. Cellular angiofibroma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 51 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1426-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Srivastava KN, Agarwal A. A complex fistula-in-ano presenting as a soft tissue tumor. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:298-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Deolekar S, Shaikh TP, Ansari S, Mandhane N, Karandikar S, Lal V. Pedunculated perianal lipoma: a rare presentation. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017;3:1557-1558. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Parks AG, Gordon PH, Hardcastle JD. A classification of fistula-in-ano. Br J Surg. 1976;63:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1072] [Cited by in RCA: 928] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Morris J, Spencer JA, Ambrose NS. MR imaging classification of perianal fistulas and its implications for patient management. Radiographics. 2000;20:623-35; discussion 635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Torkzad MR, Karlbom U. MRI for assessment of anal fistula. Insights Imaging. 2010;1:62-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Greten FR, Grivennikov SI. Inflammation and Cancer: Triggers, Mechanisms, and Consequences. Immunity. 2019;51:27-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 922] [Cited by in RCA: 2428] [Article Influence: 404.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tappouni RF, Sarwani NI, Tice JG, Chamarthi S. Imaging of unusual perineal masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W412-W420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sharma A, Yadav P, Sahu M, Verma A. Current imaging techniques for evaluation of fistula in ano: a review. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2020;51:130. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Maggiani F, Debiec-Rychter M, Vanbockrijck M, Sciot R. Cellular angiofibroma: another mesenchymal tumour with 13q14 involvement, suggesting a link with spindle cell lipoma and (extra)-mammary myofibroblastoma. Histopathology. 2007;51:410-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yuan Z, Wang J, Wang Y, Feng F, Pan L, Xiang Y, Shi X. Management of Vulvovaginal Cellular Angiofibroma: A Single-Center Experience. Front Surg. 2022;9:899329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |