Published online Apr 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i10.1772

Peer-review started: October 16, 2023

First decision: January 24, 2024

Revised: February 5, 2024

Accepted: March 18, 2024

Article in press: March 18, 2024

Published online: April 6, 2024

Processing time: 169 Days and 5.8 Hours

Purpureocillium lilacinum (P. lilacinum) is a saprophytic fungus widespread in soil and vegetation. As a causative agent, it is very rarely detected in humans, most commonly in the skin.

In this article, we reported the case of a 72-year-old patient with chronic lym

Pulmonary infection with P. lilacinum was exceedingly rare. While currently there are no definitive therapeutic agents, there are reports of high resistance to am

Core Tip: Pulmonary infection caused by Purpureocillium lilacinum (P. lilacinum) is exceedingly rare, with uncharacteristic clinical symptoms, signs, and imaging findings. In this case, we reported an older woman with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, long-standing ibrutinib, poor immune function, and fever and cough was admitted to a hematologic department. The patient was diagnosed with P. lilacinum pulmonary infection based on bronchoalveolar lavage fluid culture and metagenomic next-generation sequencing. Conventional antifungal agents often have inherent resistance. Isavuconazole was found to have good safety and efficacy. This is the first known use of isavuconazole for pulmonary P. lilacinum infection. After treatment with isavuconazole, the clinical symptoms of cough and fever improved, and the patient was discharged from the hospital.

- Citation: Yang XL, Zhang JY, Ren JM. Successful treatment of Purpureocillium lilacinum pulmonary infection with isavuconazole: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(10): 1772-1777

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i10/1772.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i10.1772

Purpureocillium lilacinum (P. lilacinum) is a saprophytic fungus widely found in soil and vegetation and a common con

A 72-year-old female with fever and chest tightness coughing sputum for 1 month presented at our emergency department.

The patient had no history of present illness.

She had an 11-month history of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and was treated with long-term, regular ibrutinib antitumor therapy.

The patient had no notable personal or family history.

Her physical examination was as follows: Clear consciousness, blood pressure 112/63 mmHg (14.896/8.379 kPa), respiratory rate 24/min, heart rate 102/min, body temperature 38.2 °C, fingertip oxygen saturation 98%, and moist rales in the right lung.

White blood cell 10.6 × 109/L (Normal range: 3.5 × 109/L to 9.5 × 109/L), neutrophils percentage 70.2% (Normal range: 40% to 75%), hemoglobin 98 g/L (Normal range: 115 g/L to 150 g/L), platelets 310 × 109/L (Normal range: 125 × 109/L to 350 × 109/L), and C-reactive protein 67 mg/L (Normal range: 0 mg/L to 8 mg/L). Procalcitonin 0.35 ng/mL (Normal range: 0 ng/mL to 0.05 ng/mL). Fungal D-glucan, galactomannan test and aspergillus IgG antibodies were all normal.

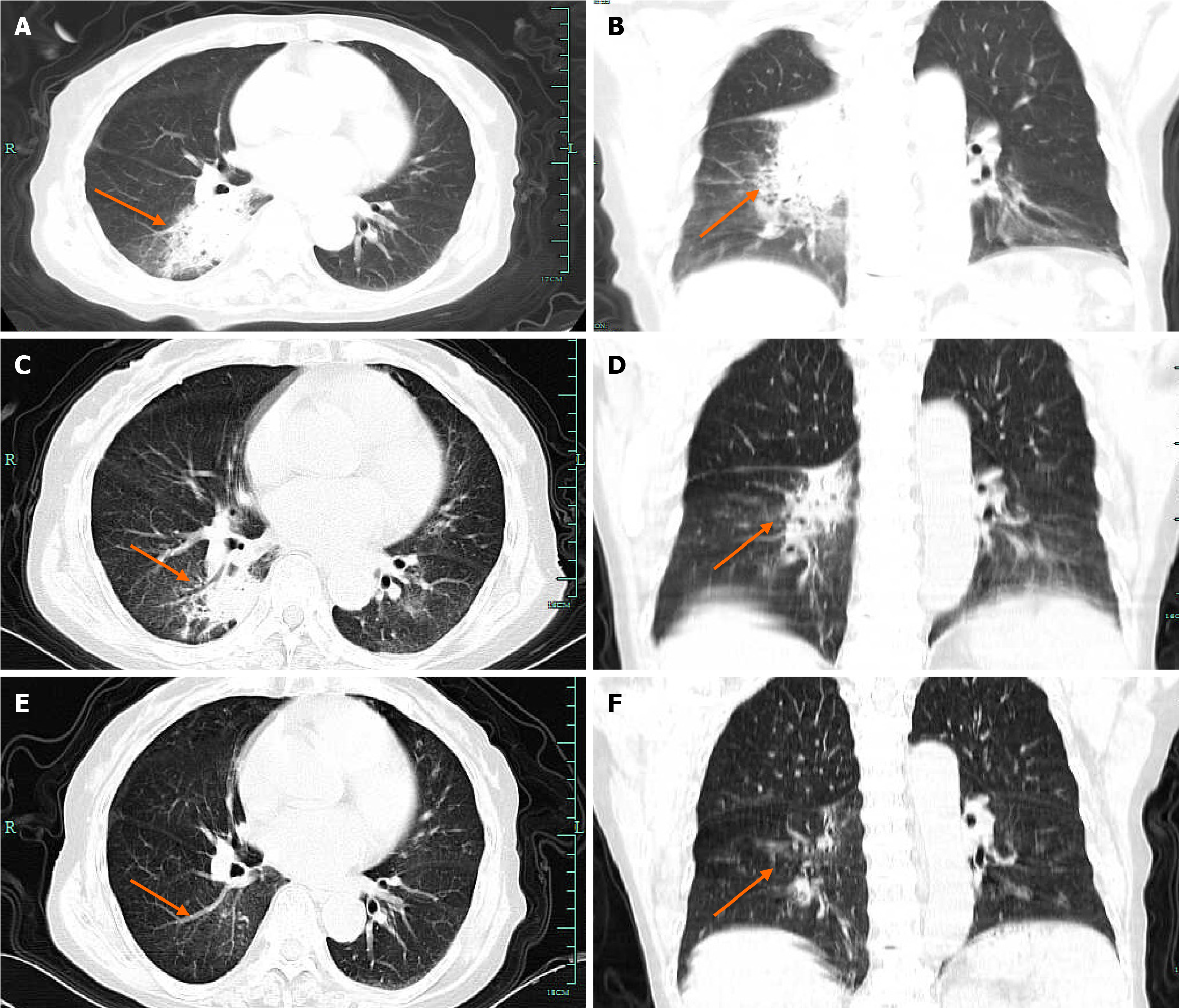

Computed tomography (CT) revealed an infection in the right lower lobe (Figure 1A and B).

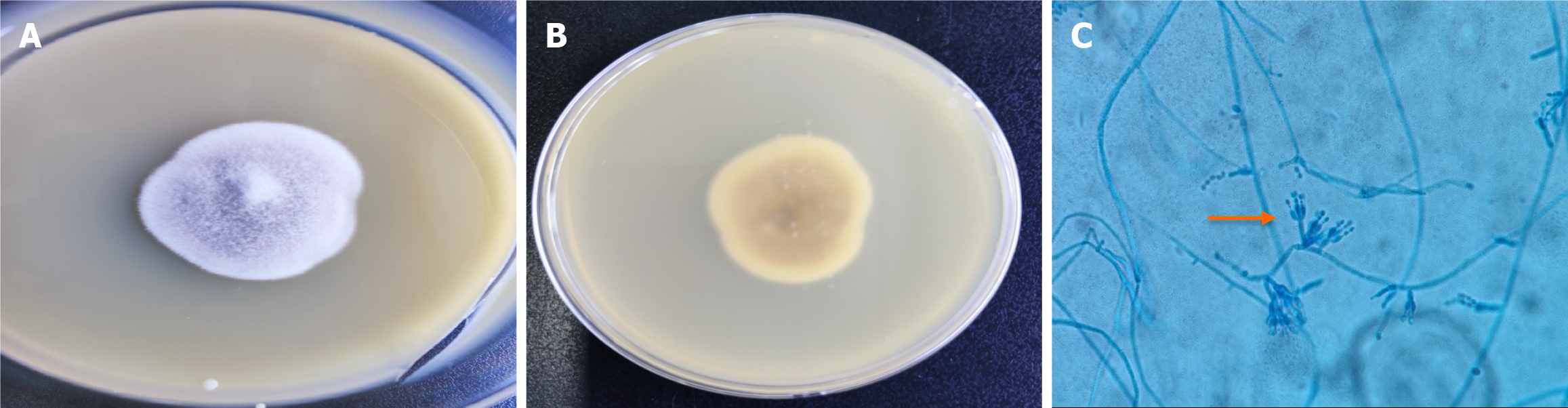

After admission to the hospital, the patient was given oxygen, and because her etiology was unknown, we administered empiric cefoperazone-sulbactam for anti-infection. Three d post-treatment, the patient remained feverish and chest tightness remained unresolved. Bronchoscopy was performed to identify the causative agent. On day 7, the colonies were approximately 3.0 cm in diameter, and the purplish colony were concentric (Figure 2A and B). Microscopic examination of the microbiota was performed, and clear, colorless, branching hyphae were observed, and the spores were infarct (Figure 2C). P. lilacinum was identified by the Vitek® MS Full Automated Rapid Microbiota Spectrometry System with a confidence interval of 99.9%. In vitro drug susceptibility for P. lilacinum was as follows: Amphotericin B = 8 μg/mL, fluconazole = 16 μg/mL, voriconazole = 1 μg/mL, and isavuconazolezole = 1 μg/mL. A sample of 1.5-3 mL of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from the patient was submitted for metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) analysis, which showed 100% homology with ATCC10114 (AY213665.1) from the GenBank database, and was classified as P. lilacinum.

The patient was diagnosed with P. lilacinum pulmonary infection and chronic lymphocytic leukemia based on medical history, physical examination, laboratory tests, imaging, BALF culture, and mNGS.

Based on pathogenic studies and in vitro drug sensitivity, we used voriconazole 200 mg tablets every 12 h for antifungal therapy. After 3 d, the patient presented with hallucinations and involuntary tremors of the hands and feet, which were considered adverse events associated with voriconazole. The patient stopped using voriconazole and was given isavuconazole tablets (200 mg every 8 h for the first 48 h, 200 mg once daily after 48 h) followed by antifungal therapy. The hallucinations and tremors of the hands and feet disappeared after 12 h of voriconazole. After 72 h of administration, her body temperature returned to normal, and cough and chest tightness improved after 1 wk.

The patient was discharged from the hospital on day 14, continuing to take isavuconazole for 3 wk, during which time she experienced no significant adverse effects. At one week after discharge, re-examination using chest CT revealed reduced lung lesions (Figure 1C and D). At 6 wk after discharge, chest CT was performed again, and the pulmonary lesions were essentially absorbed (Figure 1E and F).

P. lilacinum is a fungus found in a wide range of habitats. In 1974, Samson classified it as a penicillium-like genus based on the characteristic cone-shaped distortion of the top of the flask[6]. Cultural identification of P. lilacinum is based on its pale-violet colony color and characteristic flask morphology, and genetic sequencing of the strain may provide a more accurate identification method for clinicians[7]. P. lilacinum is rarely found in humans and is generally not considered a pathogenic mold. However, sporadic cases have been reported worldwide since 1977, when it was first described as a skin infection. It predominantly presents as a skin infection, posing the highest threat for immunocompromised patients. Sprute et al[8] analyzed 101 cases of invasive P. lilacinum infection, found that the youngest patient was 31, and the oldest was 64; male accounted for 61.1%; 31 cases (30.7%) with hematologic and neoplastic disease, 27 (26.7%) with steroid therapy, 26 (25.7%) with solid organ transplantation, and 19 (18.8%) with diabetes mellitus, with the skin being the most common site of infection (36.6%); fever, cough, and dyspnoea were the most common clinical symptoms of pulmonary infection; overall mortality was 21.8%[8].

In the present case, an older woman with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, long-standing ibrutinib, poor immune function, and fever and cough was admitted to a hematologic department and initially considered to be infected with bacteria. She was injected with cefoperazone-sulbactam as an anti-infection therapy, with no good effect.

Identifying P. lilacinum is challenging, and its histomorphology is very similar to that of Aspergillus and other hyalurocephalus pathogens[9]. There are no characteristic imaging findings. In chest CT, nodular infiltrates and cavitary lesions were common findings[8]. In our case, there was a probability of progression from pulmonary consolidation to cavitary lesions without any treatment. To further identify the causative organisms, we cultured BALF on the medium for 7 d, observed the growth of a violet-colored colony on the dishes, and observed the microscopically characteristic infarct morphology of the bottle. Microbiome profiling and BALF mNGS further identified P. lilacinum, which provided laboratory evidence for diagnosing the pathogen.

There are only a few clinical cases of P. lilacinum, so no standard antifungal regimens exist[10]. Aguilar et al[11] showed early on that amphotericin B, miconazole, itraconazole, fluconazole, and flucytosine are less active against penicillium[11]. González performed in vitro drug susceptibility assays on 22 strains of Aspergillus pallidus, revealing that isavuconazole had a minimum inhibitory concentration of 0.2 to 2 μg/mL, amphotericin B 4 to 16 μg/mL, itraconazole 1 to 16 μg/mL, fluxonazole 16 to 64 μg/mL, voriconazole 0.5 to 4 μg/mL, posaconazole 0.5 to 2 μg/mL, and ravuconazole 0.25 to 2 μg/mL[12]. By analyzing clinical isolates of infected cases, Sprute et al[8] showed high resistance to amphotericin B and excellent in vitro activity against second-generation triazole[8]. In this case, we also performed in vitro drug susceptibility assays on isolates showing poor antifungal activity of amphotericin B and fluconazole, and excellent antifungal activity of voriconazole and isavuconazole, which is consistent with the previous literature. Our patient was administered voriconazole tablets, but on day 3 she developed hallucinations and involuntary tremors of the hands and feet, so the treatment was stopped. Isavuconazole is a second-generation triazole antifungal approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 2015 for treating invasive aspergillosis and mold diseases. It inhibits cytochrome woolly steroid 14 alpha-demethylation enzyme (CYP51), disrupts the structure and function of the fungal cell membrane by blocking the synthesis of ergosterol on the fungal cell membrane, has a higher affinity for fungal side chain CYP51 protein in its structural molecules, has a broad antifungal spectrum, and includes fungi resistant to other triazole antifungals[13]. In their study, Maertens et al[14] conducted an international multicenter, randomized, double-blind, phase III Secure clinical trial involving patients with a clinical diagnosis of invasive mold disease who were initially treated with isavuconazole and voriconazole, finding similar overall response rates (P > 0.05), with adverse drug reaction rates of 42% and 60%, respectively (P < 0.001), and lower visual, psychiatric, and liver toxicity associated with isavuconazole than with voriconazole[14]. In the vital study, Thompson et al[15] found that 38 patients with rare fungal diseases (including cryptococcosis, 9 cases of paracoccosis, 9 cases of coccidiosis, 7 cases of histoplasmosis, and 3 cases of blastomycosis) were treated with isavuconazole, with an overall response rate of 63.2% and stable disease progression in 21.1%, suggesting that isavuconazole is also an effective drug for rare invasive fungal diseases[15]. Moreover, compared with posaconazole, isavuconazole has a cost-effective option for treating invasive mold diseases in high-risk hematological patients[16]. We could identify only one case of a cutaneous infection caused by P. lilacinum used to treat a patient who was successfully cured by PubMed[17]. Huang et al[18] conducted a pharmacokinetic study of intravenous isavuconazole in healthy subjects, finding that lung tissue/plasma concentration was 1.438[18]. Caballero-Bermejo et al[19] found that isa

After 12 h of voriconazole discontinuation, the patient's hallucinations and autonomic tremor disappeared, further confirming voriconazole-associated adverse effects. After 1 wk of treatment with isavuconazole, the clinical symptoms of cough and fever improved, and the patient was discharged from the hospital on day 14, continuing to take isavuconazole for 3 wk, during which time she experienced no significant adverse effects. At 6 wk after discharge, chest CT was performed again, and the pulmonary lesions were essentially absorbed.

Pulmonary infection caused by P. lilacinum is exceedingly rare, with uncharacteristic clinical symptoms, signs, and imaging findings. Pathogenic detection is complex, and conventional antifungal agents often have inherent resistance. In our patient infected with P. lilacinum, isavuconazole was found to have good safety and efficacy, but due to the small number of patients, more studies are needed to determine the optimal treatment strategy.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Akhoundi N, United States; Shariati MBH, Iran S-Editor: Liu H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Takayasu S, Akagi M, Shimizu Y. Cutaneous mycosis caused by Paecilomyces lilacinus. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1687-1690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Salazar-González MA, Violante-Cumpa JR, Alfaro-Rivera CG, Villanueva-Lozano H, Treviño-Rangel RJ, González GM. Purpureocillium lilacinum as unusual cause of pulmonary infection in immunocompromised hosts. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2020;14:415-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McGeachie DL, Boyce AE, Miller RM. Recurrent cutaneous hyalohyphomycosis secondary to Purpureocillium lilacinum in an immunocompetent individual. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62:e411-e413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lu KL, Wang YH, Ting SW, Sun PL. Cutaneous infection caused by Purpureocillium lilacinum: Case reports and literature review of infections by Purpureocillium and Paecilomyces in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2023;50:1088-1092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Albert R, Lemaignen A, Desoubeaux G, Bailly E, Bernard L, Lacasse M. Chronic subcutaneous infection of Purpureocillium lilacinum in an immunocompromised patient: Case report and review of the literature. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2022;38:5-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Samson R. Paecilomyces and some allied hyphomycetes. Stud Mycol. 1974;6:58-62. |

| 7. | Wang Y, Bao F, Lu X, Liu H, Zhang F. Case Report: Cutaneous Mycosis Caused by Purpureocillium lilacinum. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023;108:693-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sprute R, Salmanton-García J, Sal E, Malaj X, Ráčil Z, Ruiz de Alegría Puig C, Falces-Romero I, Barać A, Desoubeaux G, Kindo AJ, Morris AJ, Pelletier R, Steinmann J, Thompson GR, Cornely OA, Seidel D, Stemler J; FungiScope® ECMM/ISHAM Working Group. Invasive infections with Purpureocillium lilacinum: clinical characteristics and outcome of 101 cases from FungiScope® and the literature. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;76:1593-1603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Khan Z, Ahmad S, Al-Ghimlas F, Al-Mutairi S, Joseph L, Chandy R, Sutton DA, Guarro J. Purpureocillium lilacinum as a cause of cavitary pulmonary disease: a new clinical presentation and observations on atypical morphologic characteristics of the isolate. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1800-1804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Corrêa-Moreira D, de Lima Neto RG, da Costa GL, de Moraes Borba C, Oliveira MME. Purpureocillium lilacinum an emergent pathogen: antifungal susceptibility of environmental and clinical strains. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2022;75:45-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Aguilar C, Pujol I, Sala J, Guarro J. Antifungal susceptibilities of Paecilomyces species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1601-1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | González GM. In vitro activities of isavuconazole against opportunistic filamentous and dimorphic fungi. Med Mycol. 2009;47:71-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee SO. Diagnosis and Treatment of Invasive Mold Diseases. Infect Chemother. 2023;55:10-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Maertens JA, Raad II, Marr KA, Patterson TF, Kontoyiannis DP, Cornely OA, Bow EJ, Rahav G, Neofytos D, Aoun M, Baddley JW, Giladi M, Heinz WJ, Herbrecht R, Hope W, Karthaus M, Lee DG, Lortholary O, Morrison VA, Oren I, Selleslag D, Shoham S, Thompson GR 3rd, Lee M, Maher RM, Schmitt-Hoffmann AH, Zeiher B, Ullmann AJ. Isavuconazole versus voriconazole for primary treatment of invasive mould disease caused by Aspergillus and other filamentous fungi (SECURE): a phase 3, randomised-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;387:760-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 555] [Cited by in RCA: 670] [Article Influence: 74.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Thompson GR 3rd, Rendon A, Ribeiro Dos Santos R, Queiroz-Telles F, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Azie N, Maher R, Lee M, Kovanda L, Engelhardt M, Vazquez JA, Cornely OA, Perfect JR. Isavuconazole Treatment of Cryptococcosis and Dimorphic Mycoses. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:356-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Han G, Xu Q, Lv Q, Li X, Shi X. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of isavuconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole for the treatment of invasive mold diseases in hematological patients: initial therapy prior to pathogen differential diagnosis in China. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1292162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Accetta J, Powell E, Boh E, Bull L, Kadi A, Luk A. Isavuconazonium for the treatment of Purpureocillium lilacinum infection in a patient with pyoderma gangrenosum. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2020;29:18-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Huang H, Xie H, Chaphekar N, Xu R, Venkataramanan R, Wu X. A physiologically based pharmacokinetic analysis to predict the pharmacokinetics of intravenous isavuconazole in patients with or without hepatic impairment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2023;65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Caballero-Bermejo AF, Darnaude-Ximénez I, Aguilar-Pérez M, Gomez-Lopez A, Sancho-López A, López García-Gallo C, Díaz Nuevo G, Diago-Sempere E, Ruiz-Antorán B, Avendaño-Solá C, Ussetti-Gil P; PBISA01‐Study Group. Bronchopulmonary penetration of isavuconazole in lung transplant recipients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2023;67:e0061323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |