Published online Mar 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i9.1963

Peer-review started: November 22, 2022

First decision: February 7, 2023

Revised: February 12, 2023

Accepted: March 3, 2023

Article in press: March 3, 2023

Published online: March 26, 2023

Processing time: 115 Days and 4.5 Hours

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide, with the fourth highest mortality among all cancers. Reportedly, in addition to adenomas, serrated polyps, which account for 15%-30% of CRCs, can also develop into CRCs through the serrated pathway. Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSAs/Ps), a type of serrated polyps, are easily misdiagnosed during endoscopy.

To observe the difference in the Wnt signaling pathway expression in SSAs/Ps patients with different syndrome types.

From January 2021 to December 2021, patients with SSAs/Ps were recruited from the Endoscopy Room of Shanghai Traditional Chinese Medicine-Integrated Hospital, affiliated with Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Thirty cases each of large intestine damp-heat (Da-Chang-Shi-Re, DCSR) syndrome and spleen-stomach weakness (Pi-Wei-Xu-Ruo) syndrome were reported. Baseline comparison of the general data, typical tongue coating, colonoscopy findings, and hematoxylin and eosin findings was performed in each group. The expression of the Wnt pathway-related proteins, namely β-catenin, adenomatous polyposis coli, and mutated in colorectal cancer, were analyzed using immunohistochemistry.

Significant differences were observed with respect to the SSAs/Ps size between the two groups of patients with different syndrome types (P = 0.001). The other aspects did not differ between the two groups. The Wnt signaling pathway was activated in patients with SSAs/Ps belonging to both groups, which was manifested as β-catenin protein translocation into the nucleus. However, SSAs/Ps patients with DCSR syndrome had more nucleation, higher β-catenin expression, and negative regulatory factor (adenomatous polyposis coli and mutated in colorectal cancer) expression (P < 0.0001) than SSA/P patients with Pi-Wei-Xu-Ruo syndrome. In addition, the SSA/P size was linearly correlated with the related protein expression.

Patients with DCSR syndrome had a more obvious Wnt signaling pathway activation and a higher risk of carcinogenesis. A high-quality colonoscopic diagnosis was essential. The thorough assessment of clinical diseases can be improved by combining the diseases of Western medicine with the syndromes of traditional Chinese medicine.

Core Tip: We aimed to observe the difference in the Wnt signaling pathway expression in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp patients with large intestine damp-heat (Da-Chang-Shi-Re) syndrome and spleen-stomach weakness (Pi-Wei-Xu-Ruo) syndrome. We observed that patients with Da-Chang-Shi-Re syndrome had a more obvious Wnt signaling pathway activation and a higher risk of carcinogenesis. A high-quality colonoscopic diagnosis was essential. The thorough assessment of clinical diseases can be improved by combining the diseases of Western medicine with the syndromes of traditional Chinese medicine.

- Citation: Qiao D, Liu XY, Zheng L, Zhang YL, Que RY, Ge BJ, Cao HY, Dai YC. Clinicopathological features and expression of regulatory mechanism of the Wnt signaling pathway in colorectal sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with different syndrome types. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(9): 1963-1973

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i9/1963.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i9.1963

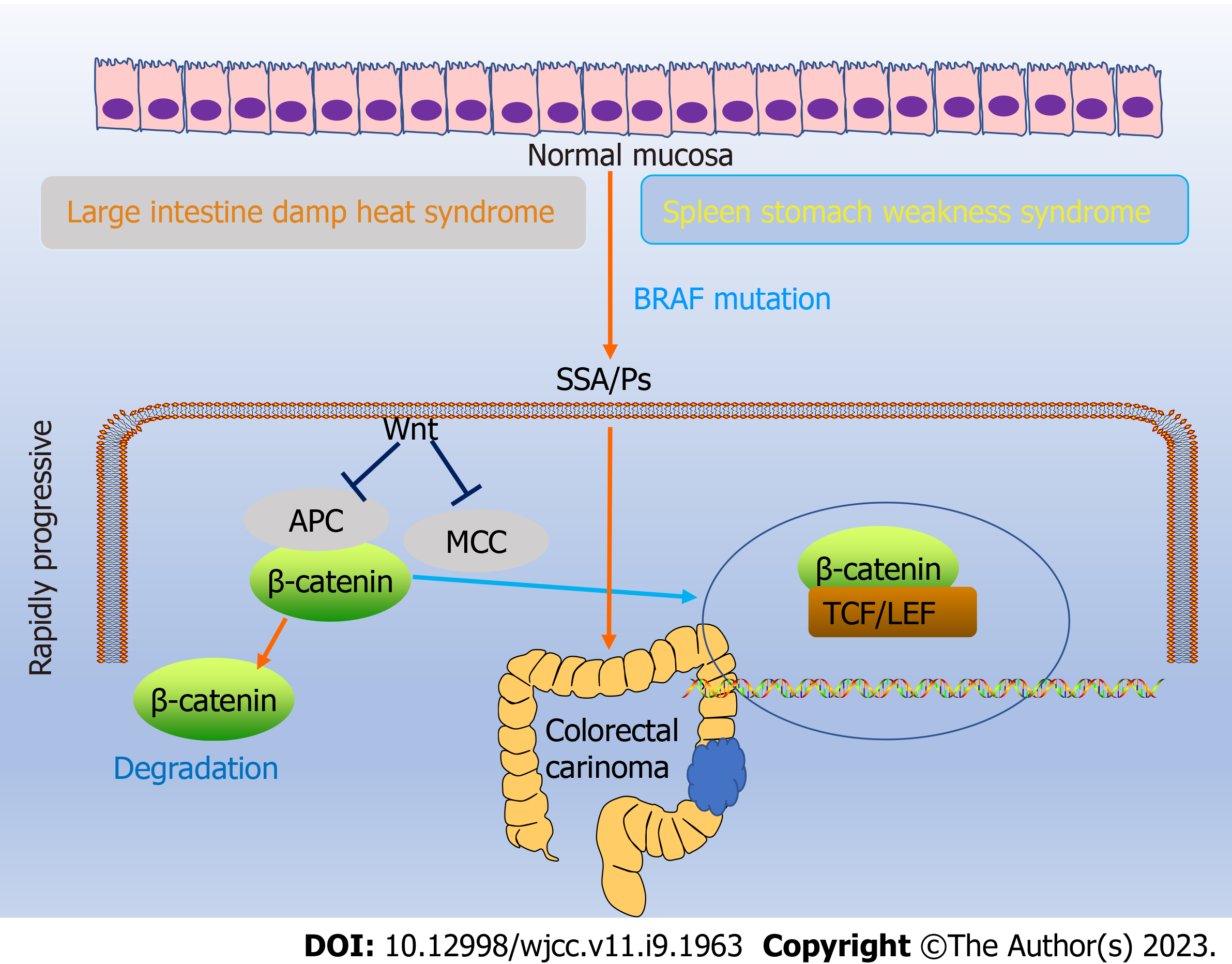

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide, with the fourth highest mortality among all cancers. Every year, CRC causes approximately 900000 cancer-related deaths and accounts for 10% of all cancer diagnoses[1]. Precancerous colorectal lesions include colorectal polys, with the classic adenoma CRC pathway being the commonest carcinogenic pathway. Reportedly, in addition to adenomas, serrated polyps, which account for 15%-30% of CRC, can also develop into CRCs through the serrated pathway[2,3]. Serrated polyps are characterized by serrated crypt structures. According to the World Health Organization classification in 2010, serrated polyps can be divided into three subtypes, which are as follows: Hyperplastic polyps (HPs), sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSAs/Ps), and traditional serrated adenomas[4]. Similar endoscopic manifestations are observed for SSAs/Ps and HPs; hence, they are easily misdiagnosed under endoscopy. Endoscopists must therefore deepen their expertise in SSAs/Ps to improve the rate of diagnosis[5]. As per traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), SSAs/Ps are “enteromas,” referring to single or multiple vegetations in the colorectal mucosa, characterized by abdominal pain or abdominal fullness and discomfort, loose or mucinous stools, or hematochezia and constipation[6]. The large intestine damp-heat (Da-Chang-Shi-Re, DCSR) syndrome and spleen-stomach weakness (Pi-Wei-Xu-Ruo, PWXR) syndrome are commonly observed in patients with “enteromas”[7]. The Wnt signaling pathway plays a crucial role in homeostatic renewal, cell proliferation, and colorectal epithelium differentiation. The sporadic occurrence of an enteroma is brought about by the abnormal activation of the Wnt signaling pathway[8]. Abnormal activation of the classical Wnt signaling pathway with β-catenin as the core in serrated polyps might be an early event of carcinogenesis[9]. TCM is based on syndrome differentiation and treatment. Whether the Wnt signaling pathway through β-catenin, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), and mutated in CRC (MCC) protein expression vary in SSA/Ps patients with different syndrome types warrants research. This study aimed to provide new ideas and a theoretical basis for differentiating “enteromas” using TCM, guide clinical treatment and evaluate prognosis, and enrich the scientific connotation of “treating the same disease with different methods” in TCM by observing the difference in the Wnt pathway expression in SSA/Ps patients with different syndrome types.

This was a single-center, parallel, controlled trial conducted at Shanghai TCM-Integrated Hospital, affiliated with Shanghai University of TCM and registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2000038536). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the trial. The Ethics Committee of Shanghai TCM-Integrated Hospital (2020-091-1) approved the experimental protocol, and the research method was not significantly modified during the study.

Inclusion criteria: The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) A diagnosis consistent with that of SSA/Ps; (2) The TCM syndrome differentiation conforms to “enteroma” DCSR or PWXR; (3) Age ranging from 18 to 70 years; and (4) Voluntary participation in the study, along with signed informed consent. DCSR syndrome was defined as follows: (1) Main symptoms included increased stool frequency, yellow-brown stools with a foul odor, a feeling of incomplete evacuation with a burning sensation around the anus, and red tongue with a yellow coating; and (2) Secondary symptoms included abdominal pain, urgent defecation, thirst and scanty urine, constipation or a feeling of incomplete evacuation, feverish sensations, yellow urine, a clouded heavy head and body, and a soft, rapid, or slippery pulse. PWXR syndrome was defined as follows: (1) Main symptoms included abdominal distension, particularly after consuming greasy food, recurrent loose stools, lassitude, shortness of breath and lazy words, and a pale tongue with a thin, white coating; and (2) Secondary symptoms included gastric or abdominal distension, cold limbs and cold intolerance, lusterless face, poor appetite, loose stools, and a weak and thready pulse. The syndrome was determined if two main symptoms and more than three secondary symptoms were present.

Exclusion criteria: The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients aged < 18 years or > 70 years and pregnant and lactating women; (2) Patients without a pathological diagnosis of SSA/Ps; (3) Patients in whom colonoscopy was contraindicated or those who could not undergo colonoscopy for other reasons; (4) A colonoscopic diagnosis of enteritis, intestinal ulcer, or non-colorectal polyps; (5) Digestive tract tumors; (6) Patients with serious primary diseases, such as cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, liver and kidney diseases, hematological diseases, and psychosis; and (7) Syndrome type established without the presence of superficial symptoms. An attending physician with 5 years of experience diagnosed the TCM syndrome type based on the patient’s symptoms, signs, tongue coating, and pulse. Another attending physician with 5 years of experience then reviewed the diagnosis. If the two TCM doctors had varying opinions on the syndrome differentiation, a deputy director with ≥ 10 years of experience differentiated and classified the syndromes, and the final diagnosis was based on a majority in terms of opinion.

General information: The general information comprised data on sex, age, the SSA/P site (right colon, left colon, or rectum), clinical symptoms (constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, or mild or no symptoms), tongue coating, and pulse condition.

Colonoscopy and histological staining: An attending physician or an associate chief physician with >3 years of experience performed the colonoscopy using an Olympus GIF HQ290 colonoscope with a preoperative Boston bowel preparation scale score of ≥ 7 and a withdrawal time of ≥ 6 min[10]. The specimen was obtained by colonoscopy, following which it was fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin and stained using hematoxylin and eosin. Two pathologists who were blinded to the endoscopic results of the patient established the pathological diagnosis. Multiple adenomas/polyps with the largest diameter were recorded, and the pathological records revealed the highest degree of malignancy.

Immunohistochemical analysis: The β-catenin, APC, and MCC protein expression in the colonic mucosa were detected using immunohistochemistry (the streptavidin-peroxidase-biotin method). We used β-catenin (ab223075; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, United States), APC (ab40778; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, United States), and MCC (PA5-57934; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). Three pictures were randomly taken from each slice under × 200 magnification, and Image Pro Plus 6.0 was used to semi-quantitatively analyze the protein expression area, after which its average optical density was measured (average optical density = integrated optical density/area of the target distribution area).

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 24.0 was used to perform statistical analysis (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). The χ2 test was used for count data, and the mean ± standard deviation was used for measurement data. One-way analysis of variance was used for measurement data between groups, and the least significant difference test was used for comparison between groups. Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test was used for non-normally distributed data. Pearson’s method was used for the correlation analysis. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

From January 2021 to December 2021, patients with SSAs/Ps were recruited from the Endoscopy Room of Shanghai TCM-Integrated Hospital, affiliated with the Shanghai University of TCM. Thirty cases each of DCSR syndrome and PWXR syndrome were recruited. Baseline comparison of general data (Table 1), typical tongue coatings (Figure 1), colonoscopic findings (Figure 2), and the hematoxylin and eosin findings (Figure 3) of each group are presented in the respective tables/figures. Significant differences in the SSA/Ps size were observed between the two groups, while no differences were observed in terms of the other aspects.

| DCSR syndrome, n = 30 | PWXR syndrome, n = 30 | P value | ||

| Sex | 0.791 | |||

| Male | 19 | 18 | ||

| Female | 11 | 12 | ||

| Age in yr | 58.800 ± 9.290 | 58.900 ± 7.097 | 0.578 | |

| Size in cm | 0.800 ± 0.435 | 0.520 ± 0.219 | 0.001 | |

| Location | 0.158 | |||

| Right half of the colon | 9 | 4 | ||

| Left half of the colon | 13 | 20 | ||

| Rectum | 8 | 6 | ||

| Clinical symptoms | 0.435 | |||

| Constipation | 4 | 6 | ||

| Diarrhea | 2 | 6 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 2 | 4 | ||

| Abdominal distension | 4 | 5 | ||

| Mild symptoms or asymptomatic | 18 | 11 | ||

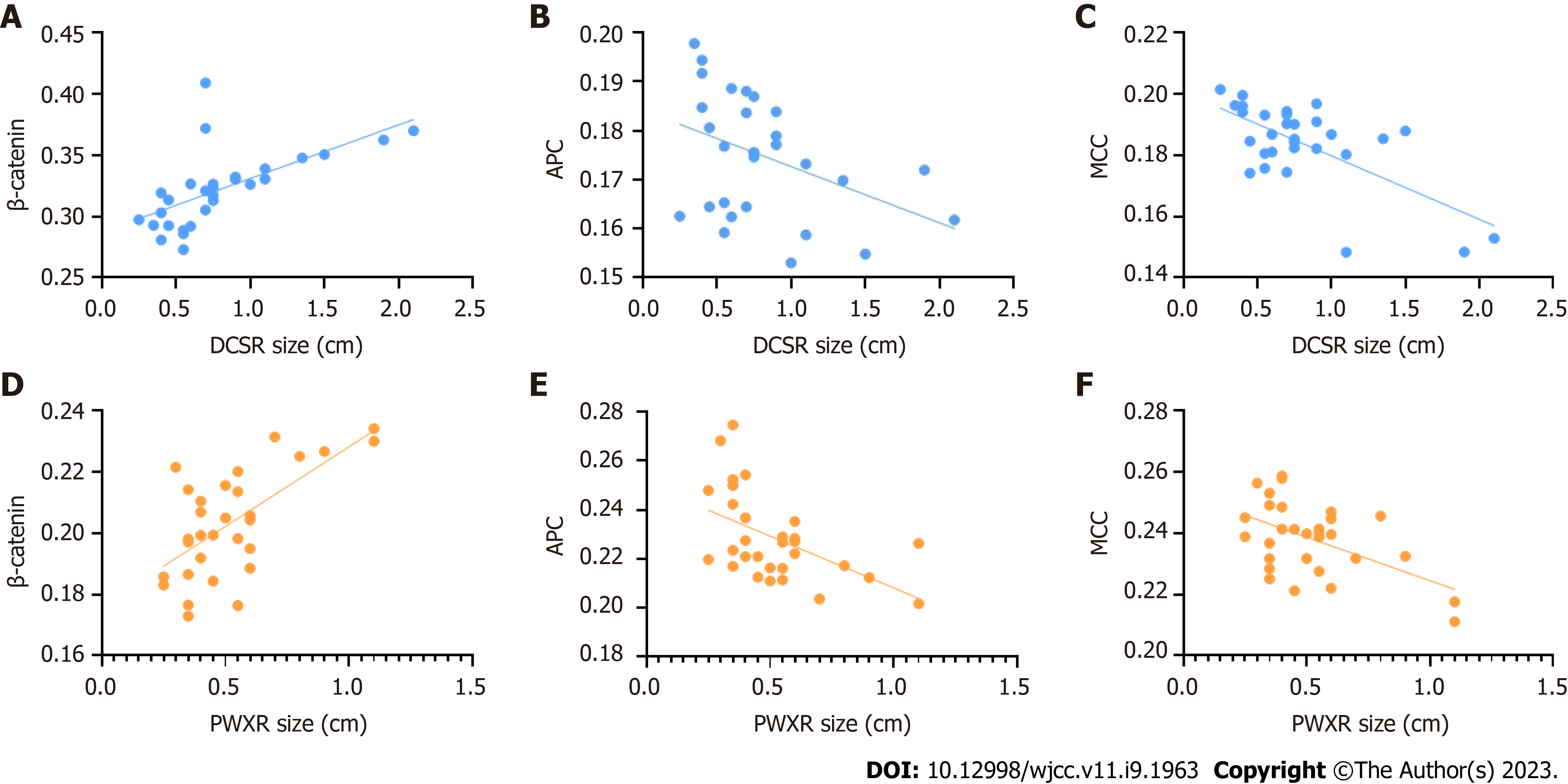

The protein expression of β-catenin, APC, and MCC in each group and the results of the statistical analysis are presented in Figure 4 and Table 2. The cell membrane generally demonstrated positive β-catenin expression, while β-catenin overexpression was observed in the cytoplasm or nucleus, which is referred to as ectopic expression. The positive expression area of β-catenin in patients with DCSR syndrome significantly increased compared with that of the patients with PWXR syndrome, with more nucleation observed in patients with DCSR syndrome. APC and MCC positive cells were observed in the cytoplasm as brown-yellow particles. The positive expression areas of APC and MCC in patients with DCSR syndrome significantly decreased compared with those of the patients with PWXR syndrome. The SSA/Ps size in patients with DCSR and PWXR was positively correlated with the β-catenin expression, with the results being statistically different (P = 0.0002 vs P < 0.0001), while the SSA/Ps size in patients with DCSR and PWXR was negatively correlated with APC and MCC expression (P = 0.0259 vs P = 0.0034 and P < 0.0001 vs P = 0.0029) (Figure 5).

| DCSR syndrome, n = 30 | PWXR syndrome, n = 30 | P value | |

| β-catenin | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | P < 0.0001 |

| APC | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | P < 0.0001 |

| MCC | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | P < 0.0001 |

Colonoscopy is a valuable tool for identifying SSAs/Ps; however, the detection rate using endoscopy remains low (0%-23%). Therefore, it is crucial to increase the understanding of endoscopists in terms of the endoscopic characteristics of SSAs/Ps. SSAs/Ps are flat protuberances without pedicles, with a hidden shape and pale surface, similar to the mucosal color, making it challenging to detect under conventional endoscopy, resulting in a missed diagnosis. The endoscopic features mainly include a mucus cap or a “red cap sign,” ambiguous boundaries, irregular shape, cumulus-like surface structure, glandular duct expansion, black spots in crypts, and glandular duct openings in type II-0 or II-d[11,12]. The main characteristics of SSAs/Ps are an abnormal crypt structure, including crypt expansion, irregular branch recess, the horizontal extension of the recess, and an L-shaped or inverted T-shaped basal recess[3].

Wnt signaling activation is a significant early event in most cases of CRC. Abnormal Wnt signaling pathway activation results in β-catenin translocation from the cytoplasm into the nucleus and activates the transcription of several genes with pro-proliferation effects. Simultaneously, chromosome instability occurs owing to abnormal chromosomal separation during mitosis. Studies have reported abnormal Wnt signaling activation in serrated adenomas[13]. The APC gene is located on chromosome 5q21-22 and is a negative regulator of the Wnt signaling pathway. APC could be associated with β-catenin for promoting β-catenin degradation. β-catenin, as a tumor suppressor gene, is involved in two relatively independent processes. It plays a crucial structural role in intercellular adhesion junctions and is the key component of the APC-β-catenin-T cell transcription factor signaling pathway. β-catenin primarily binds to cadherin on the cell membrane surface and participates in homogenous adhesion in normal mature cells. However, the free β-catenin in the cytoplasm is ubiquitinated by phosphate and can be degraded by the proteasome at a low level. However, the β-catenin level in the cytoplasm increases with impaired degradation, resulting in β-catenin translocation into the nucleus and T cell transcription factor binding to initiate the transcription of downstream target genes, thereby initiating tumor growth[14]. MCC is a susceptibility gene for familial colonic polyps. Studies have reported that MCC might be a significant tumor suppressor gene in the serrate carcinogenesis pathway. MCC can directly interact with β-catenin and inhibit the Wnt signaling pathway through different mechanisms in a manner similar to APC[15].

Unlike HPs, SSAs/Ps are associated with CRC risk and are considered precancerous colorectal lesions. Studies have reported that SSAs/Ps with cell dysplasia or carcinogenesis often carry the v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 mutant gene, and Wnt/β-catenin activation of the catenin pathway promotes SSA/P development compared with atypical hyperplasia or invasive cancer[16,17]. Herein, the endoscopic manifestations and pathological features of SSAs/Ps were combined with TCM macro syndrome differentiation, broadening the depth and scope of TCM observation and thereby helping to understand the disease more comprehensively.

A comparison of the baseline data revealed that the SSA/P size in patients with DCSR syndrome was significantly larger than that in patients with PWXR syndrome. Dampness and heat were diverted into the intestinal tract, forming polyps with turbid qi. Therefore, large adenomas were more common. However, long-term eating disorders affect transportation in the spleen and stomach. The essence of grain was not refined, and the blood and qi were passive. Qi deficiency and blood stasis were observed, and the phlegm was internally bound, resulting in polyps. Therefore, small polyps were more common. In terms of the clinical manifestations, some patients had constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and other symptoms, while some patients had no discomfort, which further highlights the importance of early gastrointestinal cancer screening.

Traditional white light endoscopy is the simplest method for diagnosing SSAs/Ps. Herein, we preliminarily confirmed the lesion location and size by white light endoscopy, following with other diagnostic methods based on the specific conditions of the lesion. Certain narrow-band imaging techniques were also used[18,19]. Moy et al[20] analyzed the endoscopic features of 147 cases of colonic polyposis and concluded that the surfaces covered with mucus caps and vascular thickening were important predictive features of SSAs/Ps. If endoscopy revealed polyps covered with mucus caps and thickened vessels, SSAs/Ps could be suspected, and further measures were taken to confirm the diagnosis.

The Wnt pathway-related protein expression (β-catenin, APC, and MCC) was analyzed by immunohistochemistry considering the malignant potential of SSAs/Ps[21]. The results revealed that Wnt signaling activation in the patients with SSAs/Ps belonging to both groups was manifested as β-catenin protein translocation into the nucleus. However, SSA/Ps patients with DCSR syndrome had more nucleation, higher β-catenin expression, and less expression of negative regulatory factors (APC and MCC). In addition, the SSA/P size was linearly correlated with the related protein expression in patients with DCSR and PWXR. The results suggested that SSA/P patients with DCSR syndrome might be at high risk for carcinogenesis and accelerated malignant transformation (Figure 6).

We chose conventional endoscopic treatment, including cold forceps polypectomy, cold snare polypectomy, endoscopic mucosal resection, and endoscopic submucosal dissection techniques, targeted drugs (probiotics, different Chinese herbal medicines according to the clinical symptoms based on syndrome differentiation), and diet and lifestyle modifications for such patients with SSAs/Ps. We also referred to the Japanese Digestive Association guidelines for managing colorectal polyps and the British Digestive Association guidelines for post-polypectomy surveillance[22,23]. Colonoscopy was planned 1 year after surgery in SSAs/Ps patients with DCSR syndrome with adenomas/polyps measuring > 10 mm in diameter[24].

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and its related factors serve as diagnostic and prognostic CRC indicators. Therefore, targeting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway now serves as a treatment strategy for CRC and is constantly being studied[25]. SSA/P patients with DCSR syndrome had a more obvious Wnt signaling pathway activation and a higher risk of carcinogenesis compared with SSA/P patients with PWXR syndrome. A high-quality colonoscopic diagnosis was essential. The thorough assessment of clinical diseases can be improved by combining the diseases of Western medicine with the syndromes of TCM.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide, with the fourth highest mortality among all cancers. Reportedly, in addition to adenomas, serrated polyps, which account for 15%-30% of CRCs, can also develop into CRCs through the serrated pathway. Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSAs/Ps) are a type of serrated polyps that are easily misdiagnosed under endoscopy.

Traditional Chinese medicine is based on syndrome differentiation and treatment. Whether the Wnt signaling pathway through β-catenin, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), and mutated CRC (MCC) protein expression are different in SSAs/Ps patients with different syndrome types warrants research.

We aimed to observe the difference in the Wnt signaling pathway expression in SSA/P patients with different syndrome types.

Thirty cases each of large intestine damp-heat (Da-Chang-Shi-Re, DCSR) syndrome and spleen-stomach weakness (Pi-Wei-Xu-Ruo) syndrome were reported. Baseline comparison of general data, typical tongue coatings, colonoscopic findings, the hematoxylin and eosin findings, and the β-catenin, APC, and MCC protein expression in the colonic mucosa of each group were analyzed.

Significant differences were observed between the two groups of patients with different syndrome types (P = 0.001) with respect to the SSA/P size. The other aspects did not differ between the groups. The Wnt signaling pathway was activated in patients with SSAs/Ps belonging to both groups, which was manifested as β-catenin protein translocation into the nucleus. However, SSA/P patients with DCSR syndrome had more nucleation, higher β-catenin expression, and decreased negative regulatory factor (APC and MCC) expression (P < 0.0001) than SSA/P patients with Pi-Wei-Xu-Ruo syndrome. In addition, the SSA/P size was linearly correlated with the related protein expression.

Patients with DCSR syndrome had a more obvious Wnt signaling pathway activation and a higher risk of carcinogenesis.

A high-quality colonoscopic diagnosis was essential. The thorough assessment of clinical diseases can be improved by combining the diseases of Western medicine with the syndromes of traditional Chinese medicine.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Belder N, Turkey; Kumar A, India S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM, Wallace MB. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2019;394:1467-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1570] [Cited by in RCA: 3029] [Article Influence: 504.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Murakami T, Sakamoto N, Nagahara A. Clinicopathological features, diagnosis, and treatment of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia/carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:1685-1695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Murakami T, Sakamoto N, Nagahara A. Endoscopic diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with and without dysplasia/carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3250-3259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 4. | Kim ER, Chang DK. How to Detect Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyps. Clin Endosc. 2018;51:313-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lui RN, Sung JJY. Sessile serrated adenoma/polyps: Why we should be working flat out to understand more about these flat lesions? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:1667-1668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tuo LY, Du WZ, Lyu K, Xu W. Analysis of Traditional Chinese Medicine Syndrome Types in 97 Cases of Inflammatory Polyps. World Chinese Medicine. 2019;14:224-227. |

| 8. | Cheng X, Xu X, Chen D, Zhao F, Wang W. Therapeutic potential of targeting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;110:473-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fu X, Li L, Peng Y. Wnt signalling pathway in the serrated neoplastic pathway of the colorectum: possible roles and epigenetic regulatory mechanisms. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:675-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tseng CW, Hsieh YH, Koo M, Leung FW. Comparing right colon adenoma detection rate during water exchange and air insufflation: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Tech Coloproctol. 2022;26:35-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hazewinkel Y, López-Cerón M, East JE, Rastogi A, Pellisé M, Nakajima T, van Eeden S, Tytgat KM, Fockens P, Dekker E. Endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas: validation by international experts using high-resolution white-light endoscopy and narrow-band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:916-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Uraoka T, Higashi R, Horii J, Harada K, Hori K, Okada H, Mizuno M, Tomoda J, Ohara N, Tanaka T, Chiu HM, Yahagi N, Yamamoto K. Prospective evaluation of endoscopic criteria characteristic of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:555-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hashimoto T, Yamashita S, Yoshida H, Taniguchi H, Ushijima T, Yamada T, Saito Y, Ochiai A, Sekine S, Hiraoka N. WNT Pathway Gene Mutations Are Associated With the Presence of Dysplasia in Colorectal Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:1188-1197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xiao J, Lv D, Zhou J, Bei Y, Chen T, Hu M, Zhou Q, Fu S, Huang Q. Therapeutic Inhibition of miR-4260 Suppresses Colorectal Cancer via Targeting MCC and SMAD4. Theranostics. 2017;7:1901-1913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Luo XS, Wang HP, Zhu XJ, Li SG, Long XK, Jiang SY, Zhang QQ. Correlation between positive KRAS mutation and P53 and MCC in colorectal cancer. J Dig Oncol. 2021;13:125-129. |

| 16. | Ashktorab H, Delker D, Kanth P, Goel A, Carethers JM, Brim H. Molecular Characterization of Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyps From a Large African American Cohort. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:572-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Murakami T, Akazawa Y, Yatagai N, Hiromoto T, Sasahara N, Saito T, Sakamoto N, Nagahara A, Yao T. Molecular characterization of sessile serrated adenoma/polyps with dysplasia/carcinoma based on immunohistochemistry, next-generation sequencing, and microsatellite instability testing: a case series study. Diagn Pathol. 2018;13:88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Parikh ND, Chaptini L, Njei B, Laine L. Diagnosis of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with image-enhanced endoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2016;48:731-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Suzuki Y, Ohata K, Matsuhashi N. Delineating sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with acetic acid spray for a more accurate piecemeal cold snare polypectomy. VideoGIE. 2020;5:519-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Moy BT, Forouhar F, Kuo CL, Devers TJ. Endoscopic Features of Mucous Cap Polyps: A Way to Predict Serrated Polyps. Clin Endosc. 2018;51:368-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Neary PM, Schwartzberg DM, Bora Cengiz T, Kalady MF, Church JM. Aspects of the Natural History of Sessile Serrated Adenomas/Polyps: Risk Indicators for Carcinogenesis in the Colorectal Mucosa? Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:1380-1385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tanaka S, Saitoh Y, Matsuda T, Igarashi M, Matsumoto T, Iwao Y, Suzuki Y, Nishida H, Watanabe T, Sugai T, Sugihara K, Tsuruta O, Hirata I, Hiwatashi N, Saito H, Watanabe M, Sugano K, Shimosegawa T; Japanese Society of Gastroenterology. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for management of colorectal polyps. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:252-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rutter MD, East J, Rees CJ, Cripps N, Docherty J, Dolwani S, Kaye PV, Monahan KJ, Novelli MR, Plumb A, Saunders BP, Thomas-Gibson S, Tolan DJM, Whyte S, Bonnington S, Scope A, Wong R, Hibbert B, Marsh J, Moores B, Cross A, Sharp L. British Society of Gastroenterology/Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland/Public Health England post-polypectomy and post-colorectal cancer resection surveillance guidelines. Gut. 2020;69:201-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 52.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shichijo S, Yamaguchi S, Nakamatsu D, Inoue T, Nakahara M, Ogiyama H, Yamada T, Kinoshita K, Ishihara R, Michida T, Nishida T, Tsujii Y, Hayashi Y, Shinzaki S, Fukui K, Ito Y, Kitamura M, Honma K, Morii E, Takehara T; Osaka Gut Forum. Local recurrence after endoscopic resection of sessile serrated lesions: A multicenter prospective study by the Osaka Gut Forum. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:2306-2312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bian Y, Wang G, Zhou J, Yin G, Liu T, Liang L, Yang X, Zhang W, Ni K, Tang D, Yu Y. Astragalus membranaceus (Huangqi) and Rhizoma curcumae (Ezhu) decoction suppresses colorectal cancer via downregulation of Wnt5/β-Catenin signal. Chin Med. 2022;17:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |