Published online Mar 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i8.1837

Peer-review started: December 6, 2022

First decision: January 17, 2023

Revised: February 2, 2023

Accepted: February 17, 2023

Article in press: February 17, 2023

Published online: March 16, 2023

Processing time: 91 Days and 0.2 Hours

At present, with the development of technology, the detection of cryptococcal antigen (CRAG) plays an increasingly important role in the diagnosis of cryptococcosis. However, the three major CRAG detection technologies, latex agglu

Core Tip: Cryptococcosis is a pulmonary or disseminated infectious disease caused by Cryptococcus, which mainly causes pneumonia and meningitis, but also skin, bone or internal organs infection. the three major cryptococcal antigen detection technologies, latex agglutination test, lateral flow assay and Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay, have certain limitations. Although these techniques do not often lead to false-positive results, once this result occurs in a particular group of patients (such as human immunodeficiency virus patients), it might lead to severe consequences. Therefore, once the test results are inconsistent with the clinical symptoms, it is necessary to reexamine the samples carefully.

- Citation: Chen WY, Zhong C, Zhou JY, Zhou H. False positive detection of serum cryptococcal antigens due to insufficient sample dilution: A case series. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(8): 1837-1846

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i8/1837.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i8.1837

Cryptococcosis is a pulmonary or disseminated infectious disease caused by Cryptococcus, which mainly causes pneumonia and meningitis, but also skin, bone or internal organs infection. Clinically, combined with clinical manifestations and microscopic examination results, the diagnosis was made, and then confirmed by fungal culture or tissue staining. Infection is caused by inhalation of Cryptococcus in human respiratory tract, and the primary infection focus is mostly lung, which causes Pulmonary cryptococcosis (PC)[1-3]. However, immunocompetent people who are infected with cryptococcosis often have insidious onset, usually without typical clinical symptoms, mostly of which are found in physical examination, and the imaging manifestations are diverse which cause trouble in the diagnosis of PC in normal population[4-6]. At present, the diagnosis of PC mainly includes three methods: Pathogen detection, immunologic test and molecular biological detection. The detection of cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide antigen (CRAG) is considered to be the most valuable and rapid serological diagnosis methods in routine examination of cryptococcosis[7]. There are three major CRAG detection technologies for now, atex agglutination test (LA), lateral flow assay (LFA) and Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay. Generally speaking, CRAG titer > 1:4 indicates cryptococcal infection, and the higher the titer, the greater the diagnostic value. Current researches suggest that CRAG test has higher sensitivity and diagnostic specificity than traditional immunodiagnostic methods and is widely applied in clinic[8-10].

However, recently, our team found 3 false positive detection cases of serum CRAG in immunocompetent patients with pulmonary lesions. One of the patients was diagnosed as PC, but the anti-cryptococcosis treatment was ineffective, and finally the patient was found to be misdiagnosed by tissue culture after lung puncture biopsy. The other two patients were detected by lung puncture and continuous re-examination of CRAG to exclude diagnosis of PC with negative results. In order to summarize the diagnosis and treatment experience of these three cases and enhance the diagnosis and treatment level of PC, the clinical data are shared as follows.

Case 1: A 53-year-old man, half a month ago, the chest computed tomography (CT) suggested a thick-walled cavity shadow in inferior lobe of left lung.

Case 2: A 67-year-old woman developed a cough without obvious inducement, accompanied by chest muffling and shortness of breath. These symptoms lasted for 2 wk.

Case 3: A 67-year-old male patient, was found to have new solid nodules in the middle lobe of the right lung during routine review.

Case 1: The patient, was found to have nodules in inferior lobe of left lung during physical examination one year ago. Half a month ago, the chest CT review of the man suggested a thick-walled cavity shadow in inferior lobe of left lung. The patient came to our hospital for further diagnosis.

Case 2: The patient developed a cough without obvious inducement, presenting paroxysmal coughing without sputum and accompanied by chest muffling and shortness of breath. These symptoms lasted for 2 wk, during which the patient had received antimicrobial therapy with oral administration of Moxifloxacin 0.5 g once a day for 5 d in the outer court, but the symptoms were still not relieved, and even aggravated. On December 19, 2018, the patient checked the lung CT examination and found that there were nodules in inferior lobe of left lung and multiple enlarged lymph nodes in mediastinum. The patient with left lung infection was further diagnosed in our hospital.

Case 3: The patient with liver transplantation two years before and had been treated with oral tacrolimus anti-rejection after liver transplantation. The patient was found to have new solid nodules in the middle lobe of the right lung during routine review and had no chief complaint. The patient came to our hospital for further diagnosis.

Case 1: A history of nodules in inferior lobe of left lung during physical examination one year ago, general health good.

Case 2: A history of asthma.

Case 3: A history of liver transplantation two years before and had been treated with oral tacrolimus anti-rejection after liver transplantation.

Case 1: The patient underwent a preliminary examination with the results of a body temperature of

Case 2: The patient underwent a preliminary examination with the results of a body temperature of

Case 3: The patient underwent a preliminary examination with the results of a body temperature of

Case 1: After admission, the CRAG detection was positive, and no other major were found in other items. The results of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were all negative. After 19 days of treatment, the detection of CRAG was negative.

Case 2: After admission, in routine hematology and biochemical laboratory examinations, tests for CRAG and T-cell detection of tuberculosis infection were positive, and no other major findings were found in other items.

Case 3: After admission, routine hematology and biochemical laboratory tests showed that the detection of CRAG was positive with no other major findings were found in other items. Before the treatment, the local hospital rechecked the test of CRAG and the result was negative. Three months later, the detection of serum CRAG showed a negative result.

Case 1: Half a month ago, the chest CT review of the man suggested a thick-walled cavity shadow in inferior lobe of left lung. After admission, high resolution CT (HRCT) examination of the patient indicated multiple nodules in inferior lobe of left lung, one with a thick-walled cavity and one with nodules, suggesting granulomatous inflammation and the possibility of cryptococcus (Figure 1A). After 19 d of treatment, chest CT reexamination, which revealed the formation of nodules with cavities in the left lower lobe. The lesions were enlarged, and internal cavity was narrowed compared to old CT photos (Figure 1B). The patient had three times of chest CT reexamination later, all of which indicated that the infection lesions in inferior lobe of left lung were shrinking.

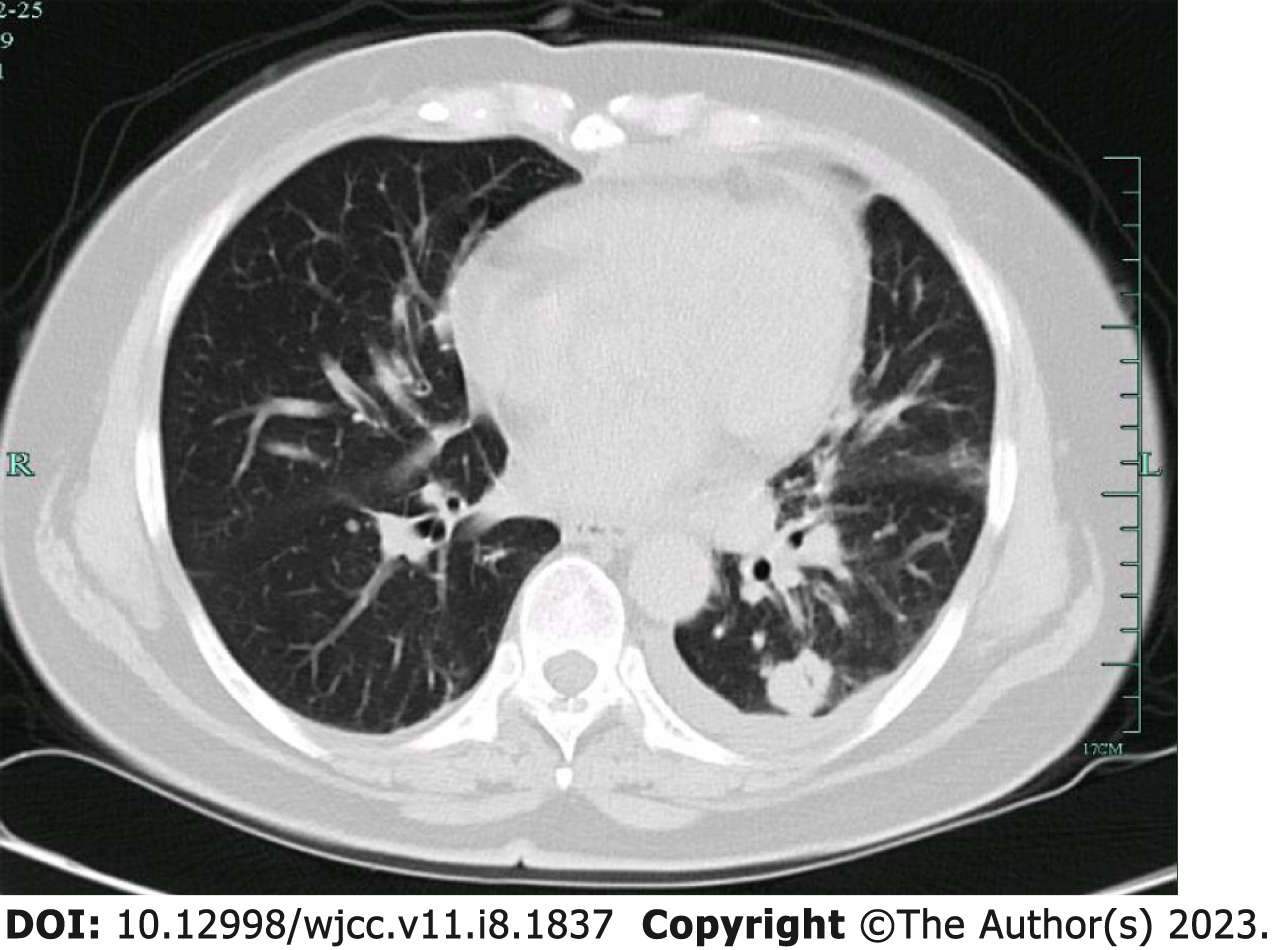

Case 2: On December 19, 2018, the lung CT examination found that there were nodules in inferior lobe of left lung and multiple enlarged lymph nodes in mediastinum. After admission, the chest HRCT of the patient indicated left inferior lobe lung cancer, multiple mediastinal lymph node metastasis, and pleural effusion with a small amount of pericardial effusion (Figure 2). Attachment: cysts in pancreatic body. B-ultrasound examination presented that there were multiple TI-RADS2 types of nodules in right thyroid, multiple lymph nodes enlargement in the IV region of bilateral neck, fatty liver, no obvious abnormality in bilateral adrenal scanning and retroperitoneal scanning. After the treatment, two chest CT reexaminations later, both indicated that the left lower pulmonary lesions were continuously shrinking.

Case 3: After admission, the chest HRCT reexamination of the patient suggested nodules in the right middle lobe and bilateral lower lobe and proliferative lesions were considered (Figure 3A). Three months later, chest CT examination of the patient in local hospital revealed the absorption of lesions in right lung.

Case 1: Half a month ago, no significant abnormality was observed in bronchoscopy. After 19 days of treatment, the patient underwent CT-guided puncture biopsy of the left pulmonary lesions. Tissue culture suggested Aspergillus spp. (Figure 1C).

Case 2: On December 25, 2018, tracheoscopy suggested mucosal swelling of the left upper lobe bronchus. Intraoperative EBUS detected lymph node enlargement in the seventh and eleventh groups, and EBUS-TBA was performed in the seventh group. At the same time, the patient also underwent CT-guided lung puncture and left supraclavicular lymph node puncture biopsy. Pathological prompts of three above examinations were as follows, EBUS-TBNA: adenocarcinoma CK7 (+), TTF-1 (+), NapsinA (+), CK5/6 (-), P63 (-), CgA (-), ALK-Lung (-); left lung puncture: adenocarcinoma CK7 (+), TTF-1 (+), NapsinA (+), CK5/6 (-), ALK-Lung (-), P63 (-), Ki-67 (25%); left supraclavicular lymph node puncture: metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma CK(pan) (+), CK7 (+), TTF-1 (+), NapsinA (+), CDX2 (-), GATA-3 (-), CK20 (+). Further genetic testing suggested a mutation in L858R.

Case 3: No evidence.

Depending on laboratory, radiological and pathological findings, Patient 1 was diagnosed as pulmonary aspergillosis.

According to laboratory, imaging and pathological examination, Patient 2 was diagnosed with lung adenocarcinoma in stage IV (cT2aN3M1c), and basically ruling out the possibility of cryptococcus infection.

Following the radiographic, clinical and laboratory examination, Patient 3 was diagnosed as community-acquired pneumonia.

The treatment regimen was Diflucan at a dosage of 400 mg intravenously once a day, and three d later the patient switched to oral administration and was discharged with medication. After 19 d oral administration of Diflucan (400 mg orally once a day), the lesions were still progressing after oral administration of Diflucan with the negative result of CRAG detection, the diagnosis of PC should be further verified and the treatment program was modified to Voriconazole 200mg orally twice a day, and the patient was discharged with medication.

According to the genetic testing results, we developed an oral Conmana 125mg tid targeted therapy regimen.

Since the patient had been treated with oral tacrolimus anti-rejection after liver transplantation and had the basis of immune injury, the possibility of PC was considered as the preliminary diagnosis combined with the imaging examination and the positive detection of CRAG. The treatment of Diflucan by oral administration was recommended. The patient then returned to the local hospital for treatment, but before the treatment, the local hospital rechecked the test of CRAG and the result was negative. After contacting our hospital, a consensus was reached that anti-cryptococcal therapy should be replaced with antimicrobial therapy.

The three times of chest CT reexamination after the treatment, all of which indicated that the infection lesions in inferior lobe of left lung were shrinking, suggesting that the treatment was effective (Figure 1D).

The two chest CT reexaminations after the treatment, both indicated that the left lower pulmonary lesions were continuously shrinking, suggesting effective treatment and basically ruling out the possibility of cryptococcus infection.

Three months after the treatment, chest CT examination of the patient in local hospital revealed the absorption of lesions in right lung, and the detection of serum CRAG showed a negative result, suggesting that the treatment was effective (Figure 3B).

Since the above three cases all showed false positive detection of serum CRAG in the same period, our team attached great importance to it. We reviewed the examination results of the three patients and checked the possible factors one by one. Finally, we found that the false positive in this batch of specimens was caused by improper handling by technicians. Common methods for detection of CRAG includes LA, LFA and Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). While we used LFA for detection, which is a simple and effective laboratory method for qualitative and semi-quantitative detection of the polysaccharide antigen in serum, plasma, whole blood and CSF by immunochromatography. The principle of LFA is essentially a “sandwich” immunochromatographic strip test, which requires adding the sample and sample dilution to a suitable container (such as a test tube), and the test strip is also placed in the container. During the test, the sample is chromatographed to the gold labelled anti-Cryptococcus antigen capture monoclonal antibody and the gold labelled control antibody located on the detection membrane. If there is a CRAG in the sample, it will bind to the gold labelled anti-cryptococcus antibody. The bound gold labelled antibody (GAB) antigen complex continues to be chromatographed on the membrane by capillarity and reacts with detection strips containing immobilized anticryptococcal monoclonal antibodies. The GAB antigen complex forms a "sandwich" structure at the detection strips and displays a visible detection strip. As long as there is normal chromatography and reagent reaction, the chromatography of any positive or negative samples will cause the gold labelled control antibody to move to the control strip, and the immobilized antibody will combine with the gold labelled control antibody to form a visible control strip. Positive test results will show two bands (test band and control band) and negative test results will show only one band (control strip). If no control strip appears, the test is invalid[8,11,12].

The kit used in our hospital is IMMY's CrAg Lateral Flow Assay (colloidal gold immunochromatography). First, add a drop of sample dilution to the microcentrifuge tube, then add 40 μL of sample. Next the white end of the CRAG test strip was immersed in the sample solution, and the result was read after 10 minutes. Diluting the sample is a critical step and usually about 50 μL of sample dilution is needed. Although this is not emphasized in the product specification, studies have shown that insufficient sample dilution is an important cause of false negative or false positives in test results[13,14]. According to the investigation, these three cases were caused by a newly employed technician who did not add enough sample diluent during the operation, which resulted in false positive in the test.

Although the detection of CRAG has high clinical value in the rapid diagnosis of cryptococcosis, we still cannot ignore the false positive results that may occur in the detection process. For once the above results are misjudged, it is easy to cause misdiagnosis. We searched on Pubmed with terms such as "cryptococcosis", "cryptococcal capsular antigen detection", "latex agglutination test", "colloidal gold immunochromatography", "enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay", and "false positive", and excluding the literature that simply discuss the "false-negative" of the above three techniques and the literature that study other methods for diagnosing cryptococcal. Only the reports on false positive results of CRAG detected by LA, LFA and ELISA were considered, including main clinical features and detection methods. A total of 4 cases were included (Table 1), as well as 8 other related studies. After reviewing the literature, we found that the three commonly used CRAG technologies (LA, LFA, and ELISA) in the market have the possibility of false positive results. Among the 4 included cases and 3 cases we reported, 4 cases adopted LA and 3 cases adopted LFA. A recently reported case of false positive adopted LA was from systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patient in active phase and complicated with Libman-Sacks endocarditis[15]. The patient developed onset of sudden disturbance of consciousness, recovered consciousness after 16 h, and the neurological examination was essentially normal, but the initial CRAG of CSF was positive. Then the patient began to receive anti- cryptococcal therapy. CSF ink staining and culture results were both negative after 3 days, and the CRAG of CSF was negative after reexamination. The first positive result was considered unreliable, so the anti-cryptococcal treatment was suspended. The reason for this false positive result may be caused by the non-specific interference of circulating autoantibodies in active SLE patients, especially when the titer of serum anti-nuclear antibodies was high[15]. In addition, it has been reported that fungal infection caused by Trichosporon asahii or bacterial infection caused by Stomatococcus or Capnocytophaga can lead to false positive results in the detection of CRAG, and these positive results usually show low titer[16-18]. Besides, there are some rare cases of false positives adopted LA, including contamination of samples by substances in the BBL Port-A-cul specimen transport bottle and the inactivation of invertase vials of the test kits[19,20].

| Ref. | Age (yr)/gender | Country | Underlying disease (including Immunosupressive disease or drug use) | Sample source/Detection method/Reagent company | Basis of diagnosis | Possible causes | Outcome |

| Matsumoto et al[24], 2019 | 58/F | United States | SLE with secondary immune thrombocytopenic purpura | CSF/LA/CALAS® Meridian Bioscience Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio | (1) Reexamination of serum LA suggested negative; (2) Both CSF ink staining and culture results were negative; and (3) Head MRI showed abnormal signals in the left superior frontal cortex, consistent with subacute ischemia; Cardiac hypertrophy suggested Libman-Sack endocarditis. The final diagnosis was "thromboembolic cerebrovascular transient ischemia" | Nonspecific interference with the autoantibodies of SLE circulation in patients | Survived |

| Augeret al[25], 2019 | 26/M | United States | None | CSF/LA | Blood and CSF culture identified Df-2 infection | Common antigenic surface components may exist in DF-2 | |

| Volozhantsev et al[26], 2020 | 33/M | United States | Aplastic anemia; after bone marrow transplantation | Serum/LA/ IM Inc, American Microscan | The autopsy confirmed Trichosporon asahiti infection | Similar structures of polysaccharides may exist in Trichosporon asahiti | Died |

| Zhu et al[27], 2018 | 29/F | United States | Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | CSF/LA/CALAS, Meridian Diagnostics, Cincinnati, Ohio, and CRYPTO-LA, International Biological Laboratories, Cranbury, New Jersey | CSF culture indicated Stomatococcus infection | Stomatococcus infection may cross-react with LA | Died |

| This case 1 | 53/M | China | None | Serum/LFA/ IMMY Immuno-Mycologics, Norman, Oklahoma, United States | (1) Anticryptococcal treatment failed; and (2) Lung puncture tissue culture suggested aspergillus | Insufficient sample dilution | Survived |

| Case 2 | 67/F | China | Bronchial asthma | Serum/LFA/ IMMY Immuno-Mycologics, Norman, Oklahoma, United States | Lung biopsy and left supraclavicular lymph node biopsy indicated lung adenocarcinoma | Insufficient sample dilution | Survived |

| Case 3 | 67/M | China | Post-orthotopic liver transplantation | Serum/LFA/ IMMY Immuno-Mycologics, Norman, Oklahoma, United States | (1) The local hospital reexamination of CRAG was negative; and (2) Anti-bacterial therapy was effective | Insufficient sample dilution | Survived |

LFA is considered to have better operability and stability than LA and the Chinese consensus believes that LFA method has a low probability of false positive, and has replaced the traditional screening method for cryptococcal infection, due to its simple operation, fast detection speed (< 15min), simple technology, less experimental instruments, and no need for refrigerated reagents[14-17]. Some studies have found that when the antigen titer in the sample is too high or the sample is not diluted enough, a post-zone phenomenon, also known as Prozone phenomenon (It is also called HOOK effect in the kit instruction), may occur which will interfere with the antigen-antibody reaction necessary for the display of positive test, resulting in false negative results[21-23]. But, accoeding to the investigation, it is puzzling that the three cases we reported had false positive results due to insufficient dilution of samples. This phenomenon is extremely rare, and only a few literatures have mentioned it, but its mechanism has never been discussed in depth. We proposed a relatively reasonable explanation. LFA detection of CRAG is achieved by capturing cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide components in serum or CSF samples with antibodies against cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide. This polysaccharide component is not unique to Cryptococcus, many microorganisms in nature secrete capsular polysaccharides (such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus group B, Streptococcus suis, etc.)[24-26]. Although LFA can detect CRAG of four major cryptococcus serotypes (type A and D are cryptococcus neoformans, type B and C are Cryptococcus Gattinii), capsular polysaccharides produced by other microorganisms are likely to be associated with CRAG in a cross-structure. False positive results may occur when the sample is not sufficiently diluted and there is a similar structure of CARG in the patient. As mentioned above, this may be the cause of false-positive capsular antigen results after certain fungal or bacterial infections.

In addition, through literature review, we found that with the progress and promotion of LFA and LA in recent years, ELISA was rarely used to detect CRAG in clinical diagnosis of cryptococcosis, but there were still reports on the comparison of three detection technologies[27-32]. Through these reports and some related works, we summarize the limitations of the three techniques in detecting CRAG (Table 2).

| Detection method | LA | LFA | ELISA |

| Sample | Cerebrospinal fluid/Serum | Cerebrospinal fluid/Serum/Plasma /Whole blood | Cerebrospinal fluid/Serum |

| Possible causes of false positive | Serum of rheumatoid factor, agarose dehydration, hydroxyethyl starch, and containing Fe3+/dL > 200 mg was present, Circular slides are not properly washed, the inactivation of Streptomyces protease in the kit and some nonspecific reactions in patients with HIV infection occur | LFA has antigenic cross-reaction with aspergillus which may lead to false positive results1; Sample dilution is insufficient2 | Samples are Infected with other microbial infections, such as Trichosporon1; Reagents and samples to be tested are contaminated2 |

At present, with the development of technology, the detection of CRAG plays an increasingly important role in the diagnosis of cryptococcosis. However, the three major CRAG detection technologies have certain limitations. Although these techniques do not often lead to false positive results, once this result occurs in a special group of patients (such as human immunodeficiency virus patients), it might lead to serious consequences. Therefore, once the test results are inconsistent with the clinical symptoms, it is necessary to carefully reexamine the samples. Especially for LFA and LA, the samples can be fully diluted or segmented dilution to avoid false positive results. It is certainly that in the diagnosis, fluid and tissue culture should also be improved, combined with imaging, ink staining and other methods to further improve the accuracy of the diagnosis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hasan S, India; Papazafiropoulou A, Greece; Yoshimatsu K, Japan S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | García J, Pemán J. [Microbiological diagnosis of invasive mycosis]. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2018;35:179-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hevey MA, George IA, Raval K, Powderly WG, Spec A. Presentation and Mortality of Cryptococcal Infection Varies by Predisposing Illness: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Am J Med. 2019;132:977-983.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bruner KT, Franco-Paredes C, Henao-Martínez AF, Steele GM, Chastain DB. Cryptococcus gattii Complex Infections in HIV-Infected Patients, Southeastern United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1998-2002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhou Y, Lin PC, Ye JR, Su SS, Dong L, Wu Q, Xu HY, Xie YP, Li YP. The performance of serum cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide antigen test, histopathology and culture of the lung tissue for diagnosis of pulmonary cryptococcosis in patients without HIV infection. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:2483-2490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Eshwara VK, Garg R, Chandrashekhar GS, Shaw T, Mukhopadhyay C. Fatal Cryptococcus gattii meningitis with negative cryptococcal antigen test in a HIV-non-infected patient. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2018;36:439-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ni LF, Wang H, Li H, Zhang ZG, Liu XM. [Clinical analysis of pulmonary cryptococcosis in non-human immunodeficiency virus infection patients]. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2018;50:855-860. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Setianingrum F, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Denning DW. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: A review of pathobiology and clinical aspects. Med Mycol. 2019;57:133-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kozel TR, Bauman SK. CrAg lateral flow assay for cryptococcosis. Expert Opin Med Diagn. 2012;6:245-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cáceres DH, Zuluaga A, Tabares ÁM, Chiller T, González Á, Gómez BL. Evaluation of a Cryptococcal antigen Lateral Flow Assay in serum and cerebrospinal fluid for rapid diagnosis of cryptococcosis in Colombia. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2017;59:e76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jitmuang A, Panackal AA, Williamson PR, Bennett JE, Dekker JP, Zelazny AM. Performance of the Cryptococcal Antigen Lateral Flow Assay in Non-HIV-Related Cryptococcosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:460-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Alves Soares E, Lazera MDS, Wanke B, Faria Ferreira M, Carvalhaes de Oliveira RV, Oliveira AG, Coutinho ZF. Mortality by cryptococcosis in Brazil from 2000 to 2012: A descriptive epidemiological study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Marr KA, Sun Y, Spec A, Lu N, Panackal A, Bennett J, Pappas P, Ostrander D, Datta K, Zhang SX, Williamson PR; Cryptococcus Infection Network Cohort Study Working Group. A Multicenter, Longitudinal Cohort Study of Cryptococcosis in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-negative People in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70:252-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Santos-Gandelman J, Rodrigues ML, Machado Silva A. Future perspectives for cryptococcosis treatment. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2018;28:625-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Liu ZY, Wang GQ, Zhu LP, Lyu XJ, Zhang QQ, Yu YS, Zhou ZH, Liu YB, Cai WP, Li RY, Zhang WH, Zhang FJ, Wu H, Xu YC, Lu HZ, Li TS; Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association. [Expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of cryptococcal meningitis]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2018;57:317-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Isseh IN, Bourgi K, Nakhle A, Ali M, Zervos MJ. False-positive cerebrospinal fluid cryptococcus antigen in Libman-Sacks endocarditis. Infection. 2016;44:803-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Westerink MA, Amsterdam D, Petell RJ, Stram MN, Apicella MA. Septicemia due to DF-2. Cause of a false-positive cryptococcal latex agglutination result. Am J Med. 1987;83:155-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | McManus EJ, Jones JM. Detection of a Trichosporon beigelii antigen cross-reactive with Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide in serum from a patient with disseminated Trichosporon infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:681-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chanock SJ, Toltzis P, Wilson C. Cross-reactivity between Stomatococcus mucilaginosus and latex agglutination for cryptococcal antigen. Lancet. 1993;342:1119-1120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wilson DA, Sholtis M, Parshall S, Hall GS, Procop GW. False-positive cryptococcal antigen test associated with use of BBL Port-a-Cul transport vials. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:702-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Stoeckli TC, Burman WJ. Inactivated pronase as the cause of false-positive results of serum cryptococcal antigen tests. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:836-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yadava SK, Fazili T. Postzone phenomenon resulting in a false-negative cerebral spinal fluid cryptococcal antigen lateral flow assay. AIDS. 2019;33:1099-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lee GH, Arthur I, Leung M. False-Negative Serum Cryptococcal Lateral Flow Assay Result Due to the Prozone Phenomenon. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kojima N, Chimombo M, Kahn DG. False-negative cryptococcal antigen test due to the postzone phenomenon. AIDS. 2018;32:1201-1202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Matsumoto Y, Miyake K, Ozawa K, Baba Y, Kusube T. Bicarbonate and unsaturated fatty acids enhance capsular polysaccharide synthesis gene expression in oral streptococci, Streptococcus anginosus. J Biosci Bioeng. 2019;128:511-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Auger JP, Payen S, Roy D, Dumesnil A, Segura M, Gottschalk M. Interactions of Streptococcus suis serotype 9 with host cells and role of the capsular polysaccharide: Comparison with serotypes 2 and 14. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0223864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Volozhantsev NV, Shpirt AM, Kislichkina AA, Shashkov AS, Verevkin VV, Fursova NK, Knirel YA. Structure and gene cluster of the capsular polysaccharide of multidrug resistant carbapenemase OXA-48-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strain KPB536 of the genetic line ST147. Res Microbiol. 2020;171:74-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhu T, Luo WT, Chen GH, Tu YS, Tang S, Deng HJ, Xu W, Zhang W, Qi D, Wang DX, Li CY, Li H, Wu YQ, Li SJ. Extent of Lung Involvement and Serum Cryptococcal Antigen Test in Non-Human Immunodeficiency Virus Adult Patients with Pulmonary Cryptococcosis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2018;131:2210-2215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kumari S, Verma RK, Singh DP, Yadav R. Comparison of Antigen Detection and Nested PCR in CSF Samples of HIV Positive and Negative Patients with Suspected Cryptococcal Meningitis in a Tertiary Care Hospital. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:DC12-DC15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tintelnot K, Hagen F, Han CO, Seibold M, Rickerts V, Boekhout T. Pitfalls in Serological Diagnosis of Cryptococcus gattii Infections. Med Mycol. 2015;53:874-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Huang HR, Fan LC, Rajbanshi B, Xu JF. Evaluation of a new cryptococcal antigen lateral flow immunoassay in serum, cerebrospinal fluid and urine for the diagnosis of cryptococcosis: a meta-analysis and systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hansen J, Slechta ES, Gates-Hollingsworth MA, Neary B, Barker AP, Bauman S, Kozel TR, Hanson KE. Large-scale evaluation of the immuno-mycologics lateral flow and enzyme-linked immunoassays for detection of cryptococcal antigen in serum and cerebrospinal fluid. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013;20:52-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Binnicker MJ, Jespersen DJ, Bestrom JE, Rollins LO. Comparison of four assays for the detection of cryptococcal antigen. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19:1988-1990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |