Published online Feb 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i4.962

Peer-review started: November 22, 2022

First decision: December 19, 2022

Revised: December 27, 2022

Accepted: January 9, 2023

Article in press: January 9, 2023

Published online: February 6, 2023

Processing time: 75 Days and 17.9 Hours

In patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, re-examination with standard upper endoscopes by experienced physicians will identify culprit lesions in a substantial proportion of patients. A common practice is to insert an adult-sized forward-viewing endoscope into the second part of the duodenum. When the endoscope tip enters after the papilla, which is a marker for the descending part of the duodenum, it is difficult to endoscopically judge how far the duodenum has been traversed beyond the second part.

We experienced three cases of proximal jejunal masses that were diagnosed by standard upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and confirmed with surgery. The patients visited the hospital with a history of melena; during the initial upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy, the bleeding site was not confirmed. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding was suspected; thus, according to guidelines, upper endoscopy was performed again. A hemorrhagic mass was discovered in the small intestine. The lesion of the first patient was thought to be located in the duodenum when considering the general insertion depth of a typical upper gastrointestinal endoscope; however, during surgery, it was confirmed that it was in the jejunum. After the first case, lesions in the second and third patients were detected at the jejunum by inserting the standard upper endoscope as deep as possible.

The deep insertion of standard endoscopes is useful for the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding.

Core Tip: In obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, guidelines recommend a second-look endoscopy. If there are negative results, enteroscopy is necessary. However, enteroscope is less commonly used than other endoscopes, and diagnosis may be delayed. We report cases of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the jejunum diagnosed with standard upper endoscopy and confirmed by surgery. In many cases, we do not know how deep the endoscope was inserted; however, we found the tip of the upper endoscope reached the jejunum and confirmed it through surgery. We recommend inserting an upper gastrointestinal endoscope deeply when performing second-look endoscopy for obscure upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Citation: Lee J, Kim S, Kim D, Lee S, Ryu K. Three cases of jejunal tumors detected by standard upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: A case series. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(4): 962-971

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i4/962.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i4.962

In clinical practice, many bleeding points can be initially identified by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy. The small intestine is frequently difficult to approach because of its anatomical structure and location, leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment. Although many types of enteroscopes have been developed, they have difficulty in diagnosing and treating patients with active bleeding, especially regarding cost limitations. Considering the maintenance costs and frequency of use, many centers do not have enteroscopes. However, in clinical settings, since a several cases of small bowel bleeding occur at the proximal jejunum, those cases can be diagnosed and treated by colonoscopy or push enteroscopy[1]. Herein, we report three cases of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding from gastrointestinal stromal tumors in jejunum diagnosed by standard upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Case 1: A 55-year-old man presented with a 3 d history of melena.

Case 2: A 74-year-old woman presented with a 3 d history of melena.

Case 3: A 77-year-old woman presented with a 2 d history of melena.

Case 1: The patient visited a regional hospital because of black stools and underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, colonoscopy, and abdominal computed tomography. However, the exact bleeding point was not identified; thus, he was referred to our clinic for further evaluation.

Case 2: The patient visited our emergency center because of black stools. She also presented epigastric pain and general weakness.

Case 3: The patient was referred to our hospital after visiting a regional hospital for black stools. She also presented general weakness.

Case 1: None.

Case 2: The patient was diagnosed with cerebrovascular accident accompanied by hypertension 17 years ago.

Case 3: The patient had been treated for cerebrovascular accidents 6 and 10 years ago.

Case 1: None.

Case 2: The patient was on antihypertensive drug therapy including aspirin and had gait disturbance because of weakness in the right upper and lower extremities.

Case 3: The patient was on antihypertensive drug therapy including aspirin. She was under rehabilitation for gait disturbance and mostly remained in the lying position.

Case 1: Vital signs were normal. The bowel sounds increased.

Case 2: Vital signs were normal. No abdominal tenderness, rebound tenderness, and palpable mass were noted.

Case 3: Vital signs were normal. The bowel sounds increased.

Case 1: Hemoglobin concentration dropped to 9.6 g/dL. Other results were within normal limits.

Case 2: Hemoglobin concentration dropped to 4.4 g/dL. Biochemical tests revealed blood urea nitrogen, 22.0 mg/dL; serum creatinine, 0.73 mg/dL; total bilirubin, 1.5 mg/dL, and other results were within normal limits.

Case 3: Hemoglobin concentration decreased to 6.0 g/dL, and other laboratory results were relatively in the normal range.

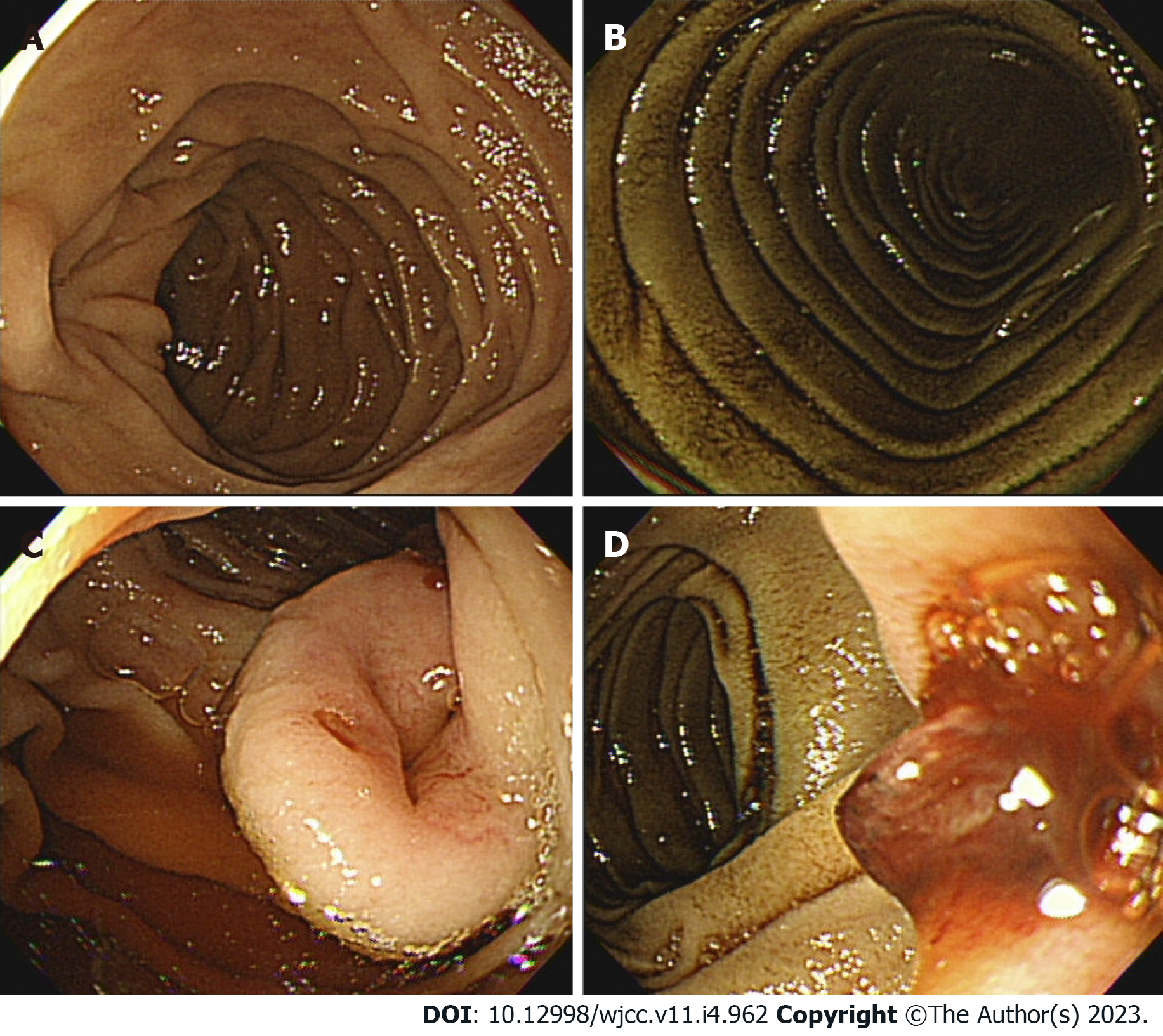

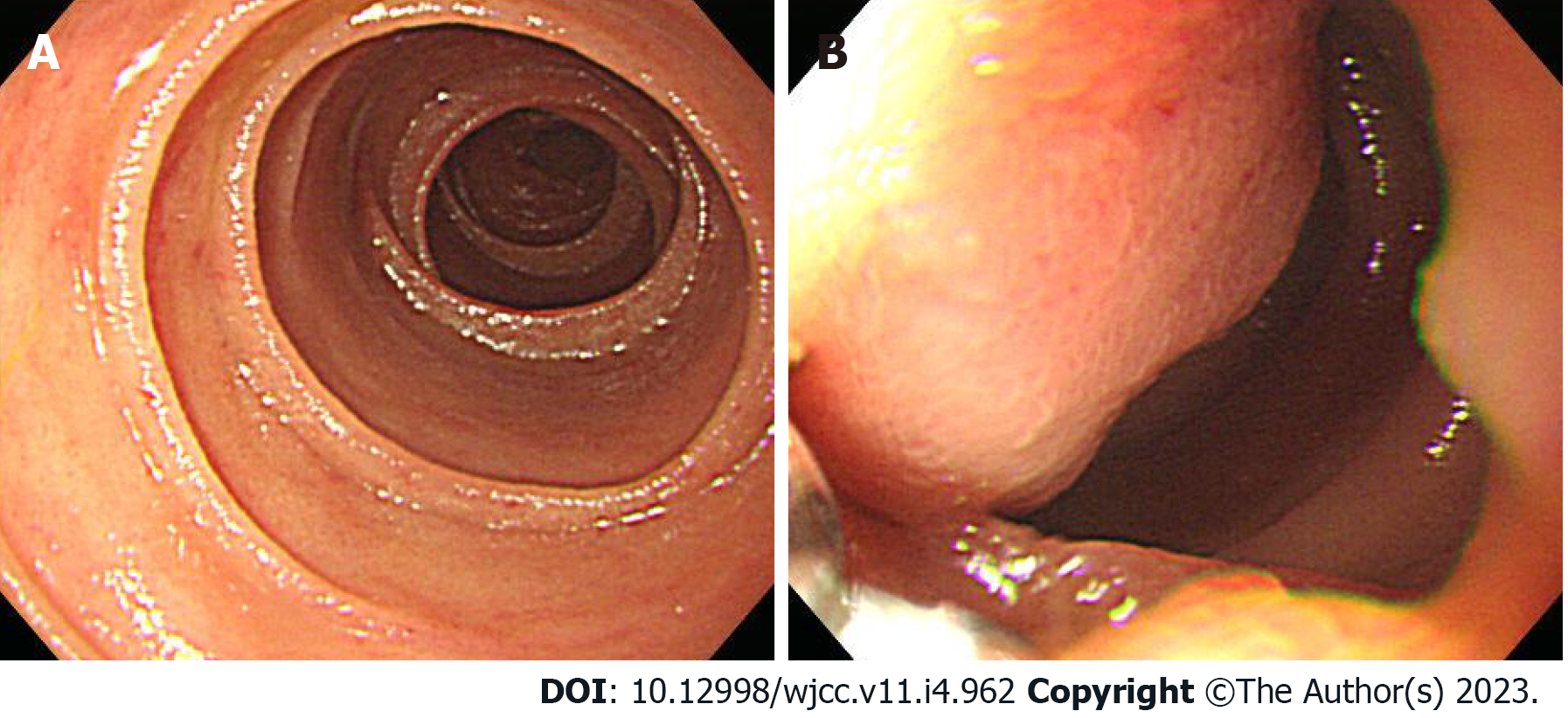

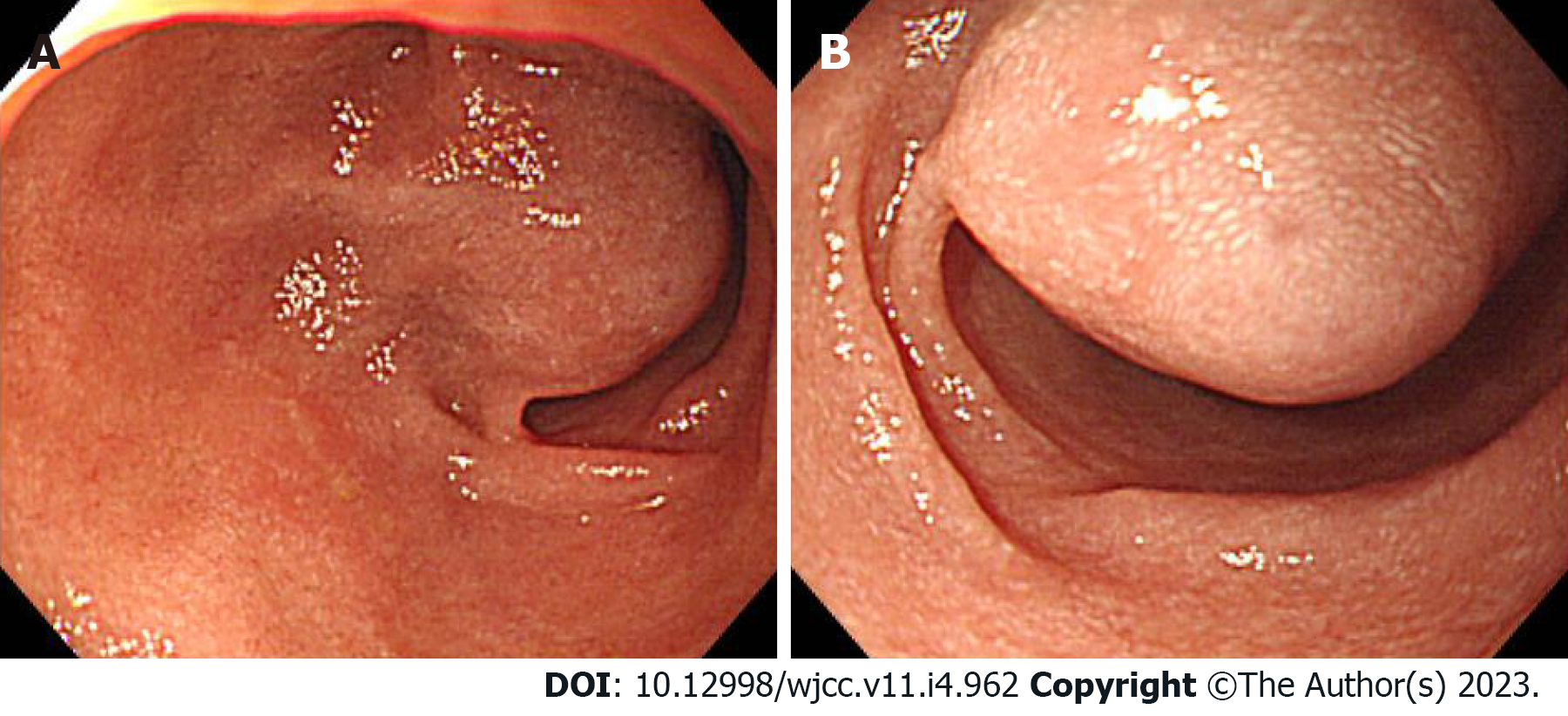

Case 1: The bleeding point was evaluated again by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy before the assessment of the small intestine. We used a video Gastroscope GIF-Q260 (working distance, 103 cm; Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Endoscopy was performed without sedation. After the stomach and the descending(second) part of the duodenum were thoroughly examined, the endoscope was maximally inserted using the axis-maintaining and bowel-shortening method as in the colonoscopy. While inserting the endoscope tip deeper from the third part of the duodenum, the color of the mucosal surface suddenly changed to dark. At that time, a 2.5 cm protruding mass of black mucosa was identified on the transitional area (Figure 1). The surface of the mass was smooth, the center was depressed, and its distal part had exposed blood vessels. Active bleeding was not noted at that time. Secondary reading of abdominal computed tomography from an outside hospital was made by a radiologist who was a subspecialist of gastrointestinal system in our hospital. According to the radiology report, intraluminal mass was noted at the proximal jejunum (Figure 2).

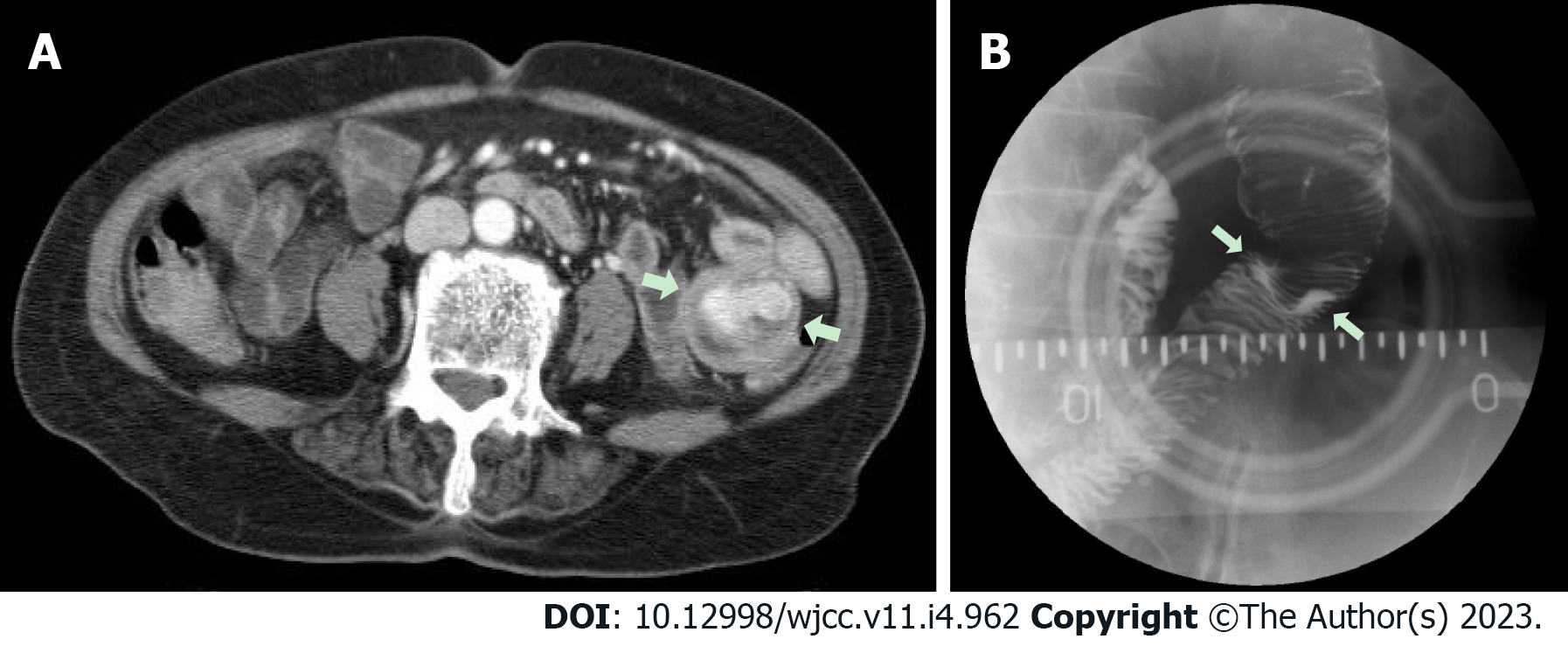

Case 2: Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed to find the bleeding points, but neither active bleeding nor a suspicious lesion was identified. On the following day, colonoscopy was performed, which revealed large amounts of black stools without suspicious bleeding points. Since black blood clots were observed in the terminal portion of the ileum, the patient was scheduled for enteroscopy. Before enteroscopy, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed again without sedation. The stomach and descending part of the duodenum were thoroughly examined with the same endoscope that was used in case 1, but no suspicious bleeding points were identified. The endoscope tip was maximally inserted deeper than the descending part of the duodenum using the axis-maintaining and bowel-shortening method with abdominal compression. During the insertion, the arrangement of the mucosal fold was altered, and a 1.5 cm protruding mass was seen at what appeared to be the jejunum (Figure 3). Abdominal computed tomography detected a 2.0 cm enhanced mass at what appeared to be the proximal jejunum (Figure 4).

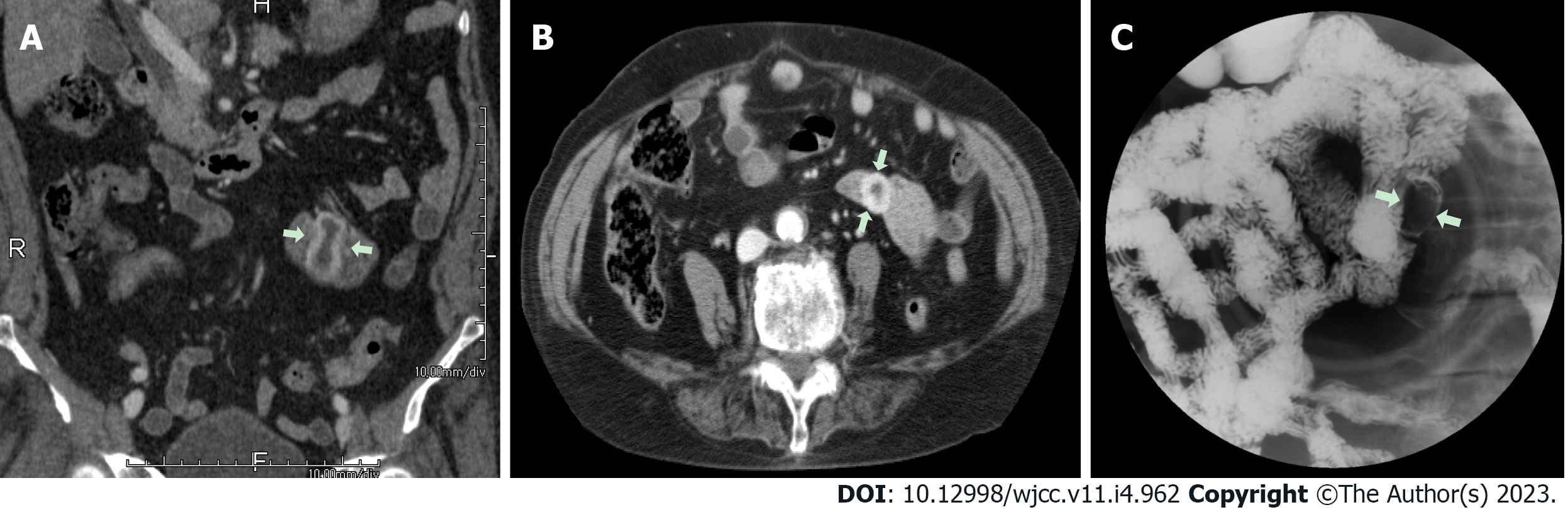

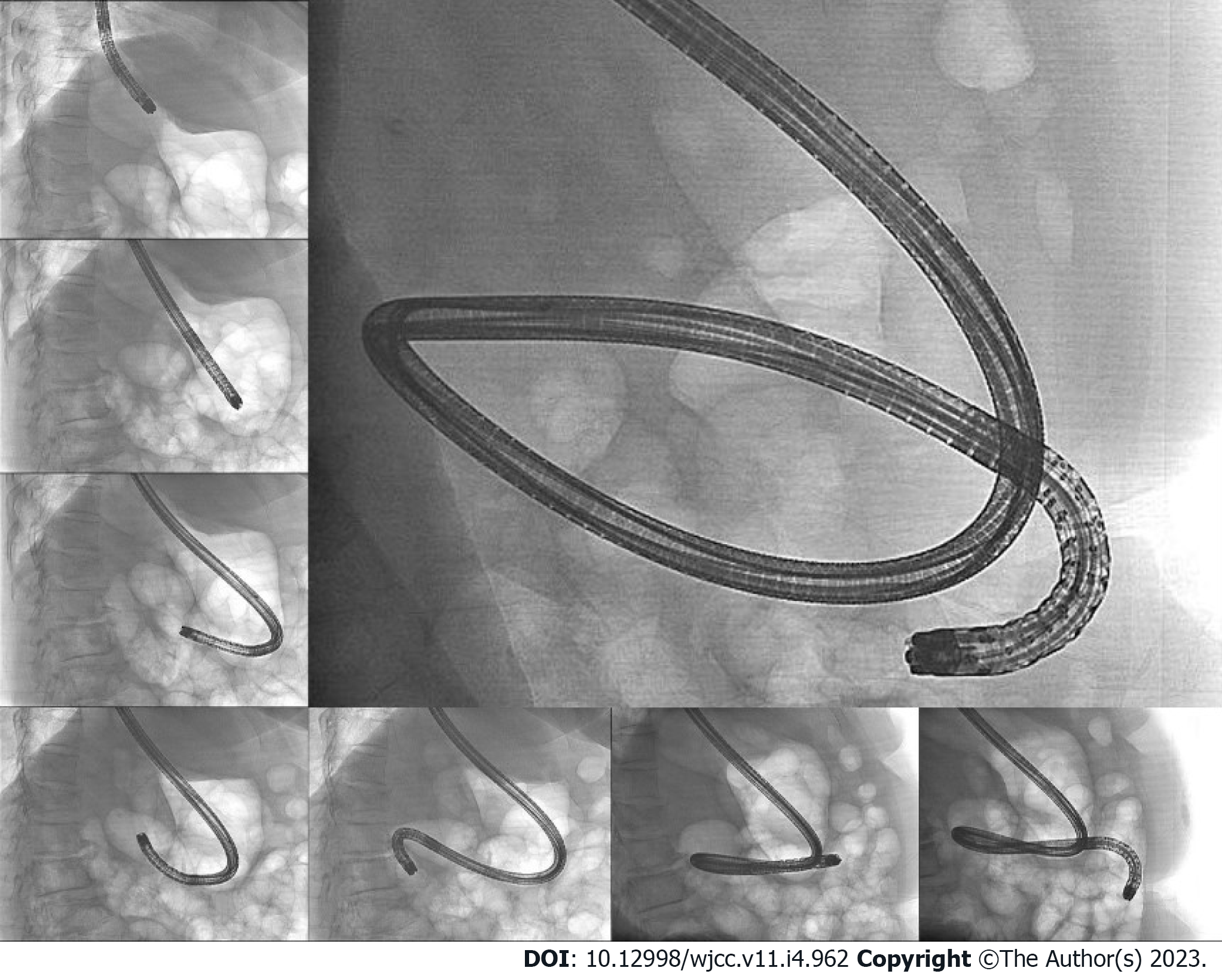

Case 3: We performed upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy, but could not find any bleeding points. Abdominal computed tomography revealed a 3.8 cm dumbbell-shaped enhancing mass in the proximal jejunum (Figure 5). To check for active bleeding and perform biopsy, endoscopic examination was decided, and previously described (as in cases 1 and 2) standard upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed without sedation. The endoscope was inserted by the technique used in the previous cases. The mass covered with normal mucosa of approximately 3 cm in size was noted at the structure suspected as the proximal jejunum, nearly filling the lumen (Figure 6). Simultaneously with endoscopy, fluoroscopy was performed to confirm the location of the tip of the scope (Figure 7). A small bowel series was conducted to determine the exact location. On small bowel series, a 2.0 cm ellipsoid filling defect lesion was observed in the proximal jejunal loops at a distance of approximately 20 cm from the Treitz ligament (Figure 5).

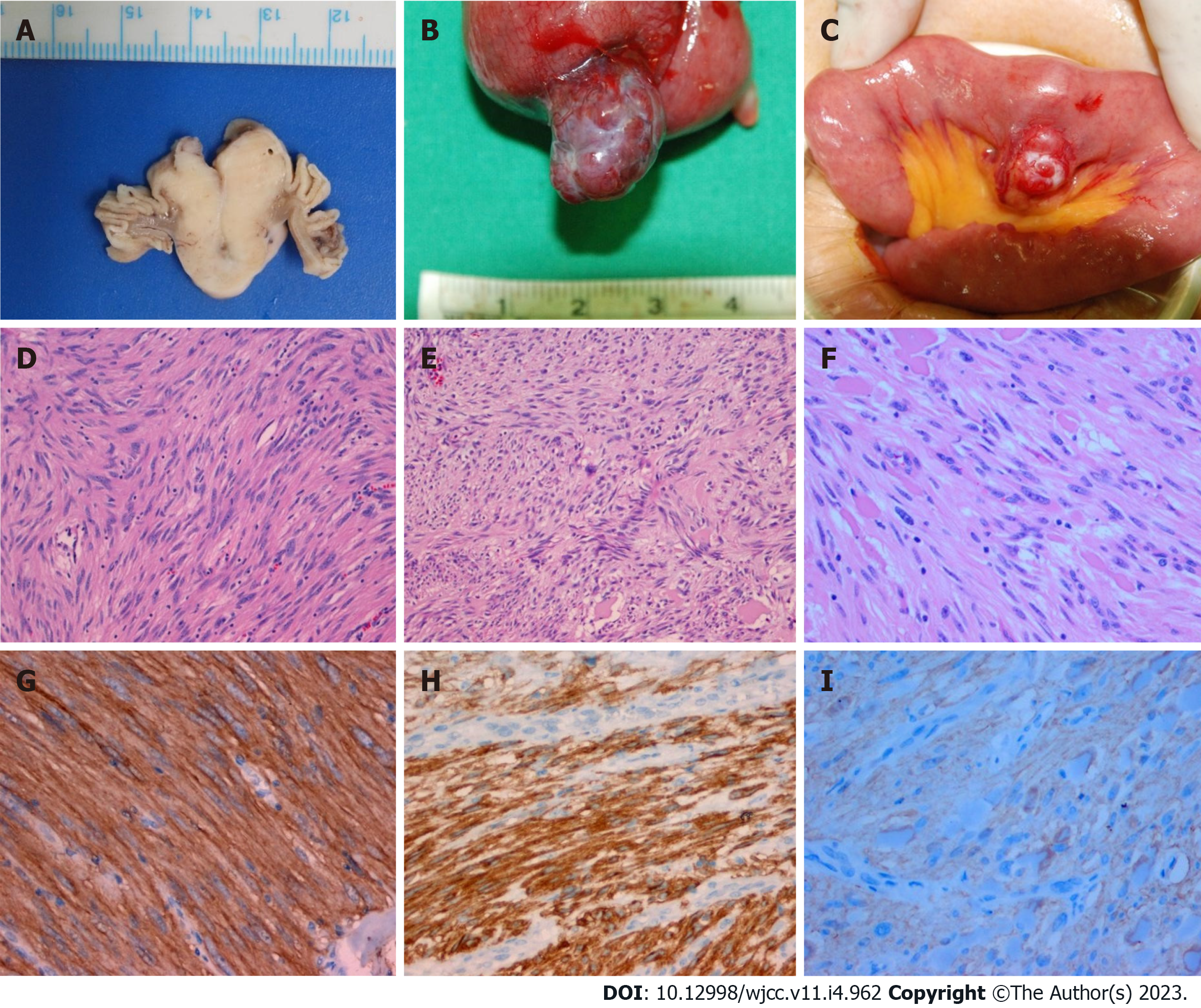

Case 1: The tumor measured 2.7 cm × 2 cm, and the mitotic count was low (< 1/50 high-power fields).

Case 2: The tumor measured 3.9 cm × 2.2 cm, and the mitotic count was low (< 1/50 high-power fields).

Case 3: The tumor measured 2.5 cm × 1.6 cm, and the mitotic count was low (< 1/50 high-power fields).

Immunohistochemical studies of all cases showed positive staining for CD 117 (c-kit) in the tumor cells (Figure 8). These findings supported a diagnosis of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) having a low risk.

Case 1: According to the imaging study, the mass was thought to be a submucosal tumor located in the duodenum or jejunum because it is thought that forward-viewing standard upper gastrointestinal endoscopes commonly cannot reach over the distal part of the duodenum. Thus, the tumor location was not accurate, and the patient was scheduled for elective operation, with various possibilities of tumor location. For instance, if the location is retroperitoneal, pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple’s operation) should be performed, which needs substantial time and skilled surgeons. While waiting for the surgery date, hematochezia suddenly developed, and emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed because of changes in the vital signs while preparing for surgery. The mass was found in the jejunum, 20 cm distal to the Treitz ligament, and segmental resection with end-to-end anastomosis was performed.

Case 2: Laparoscopic segmental small bowel resection was performed, and a protruding tumor in the proximal jejunum was identified.

Case 3: The patient underwent laparoscopic segmental small bowel resection.

This part is not available.

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding is a case in which bleeding points cannot be identified by initial upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy[2]. Causes of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding include bleeding tumors, such as malignant tumors or large adenomas, inflammatory diseases, vascular diseases, parasitic infestations, pancreaticobiliary tract diseases, and diverticula. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding occurs mostly in the small intestine; thus, methods for the diagnosis of small intestinal diseases have been extensively studied so far[2].

Numerous small bowel tests are available, and each has its advantages and disadvantages. Video capsule endoscopy has been widely used in clinical practice and has played a crucial role in the evaluation of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. However, this endoscopy does not allow for tissue biopsy or endoscopic treatment, and some lesions could be missed because it passed through the duodenum and proximal jejunum too rapidly[3]. Thus, enteroscopy is superior to video capsule endoscopy. Enteroscopy includes push enteroscopy that can examine up to 70-150 cm distal to the Treitz ligament and deep enteroscopy. Currently, several techniques of deep enteroscopy that can examine almost the entire small intestine have been developed, such as double-balloon enteroscopy, single-balloon enteroscopy, and spiral enteroscopy[4]. However, these enteroscopic procedures have some disadvantages because they are expensive, and in some cases, enteroscopic treatment is not feasible. Hemostasis through angiography is necessary when patients’ vital signs are unstable or massive active bleeding is suspected, but if there are no overt bleeding, the diagnostic yield is low[5]. Bleeding lesions are most frequently detected immediately after bleeding onset[6]. Bleeding lesions were found within the reach of standard endoscopy in 5%-25% of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, while bleeding points were not discovered on the first endoscopy[7-9]. Thus, many guidelines, especially the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline[10] and the American College of Gastroenterology clinical guideline, recommend repeating gastrointestinal endoscopy in patients whose cause is not initially determined[11]. In cases where the aforementioned endoscopic procedures were performed again under the suspicion of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, experienced endoscopists can detect the culprit lesion[12]. Fry et al[13] detected potential and definitive bleeding lesions by re-examination within the reach of conventional upper and lower endoscopes in 47.6% and 24.3% of the patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, respectively.

GISTs are rare forms of mesenchymal tumors in the gastrointestinal tract and are commonly discovered in the stomach (50%-60%) and small intestine (30%-35%) and less frequently in the colorectal area (5%) and esophagus (< 1%)[14]. In various studies of small bowel GISTs, tumors were often located in the jejunum[15-17]. Symptoms of GISTs are non-specific and vary in size and location. Small tumors (<2 cm) are mostly asymptomatic, and the most common symptom in symptomatic cases is gastrointestinal bleeding in 50% of the patients, followed by abdominal pain (20%-50%) and gastrointestinal obstruction (10%-30%)[18]. They account for 27% of the causes of small bowel bleeding[19]. According to Sass et al[20], gastrointestinal bleeding occurs in 87% of stromal tumors of the duodenum, 64% of stromal tumors of the small bowel except the duodenum, and 45% of stromal tumors of the stomach and colon including the rectum.

Byeon et al[21]. reported that double-balloon enteroscopy detected bleeding lesions in the jejunum in 18 of 30 patients with suspected gastrointestinal bleeding. They stated that the incidence of angiodysplasia was not significantly different between the jejunum and ileum (the small bowel distal to the jejunum) and that most of the erosive or ulcerative lesions and stromal tumors were found in the jejunum. In another study, in nine cases of Dieulafoy’s lesion-induced small bowel bleeding, most of the lesions were located in the proximal jejunum[22]. Another study showed that stromal tumors were found more frequently in the jejunum than in the ileum (n = 264 vs n = 161) [23]. Therefore, meticulous examination of the jejunum is extremely important in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding.

Conventional forward-viewing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, which is also called esophagogastroduodenoscopy, has been widely used to observe the small intestine up to the descending part of the duodenum. Brady et al[24] investigated the maximum reach of a flexible GIF-K2 upper endoscope (working distance, 113 cm; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and a TX-8 upper endoscope (working distance, 110 cm; ACMI, Southborough, MA, United States) using X-rays. They stated that the endoscopes reached the second part of the duodenum in 96% of the endoscopic procedures, the third part in 51%, and the small intestine distal to the fourth part in 38%. Moreover, although none of the endoscopists recognized that the endoscope tip had reached the jejunum, X-ray imaging revealed that the endoscope tip had, in fact, reached the jejunum in 6 of 55 (10.9%) patients. This result implies that conventional upper gastrointestinal endoscopy has potential in finding lesions located in the proximal part of the jejunum.

We re-examined three patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy using the axis-maintaining and bowel-shortening method as in colonoscopy and detected the bleeding lesions in the proximal part of the jejunum. In case 1, a bleeding lesion was identified by endoscopy, and computed tomography found it in the proximal part of the jejunum. However, considering that the maximum reach of upper gastrointestinal endoscopes is the duodenum, the patient was scheduled for elective operation including Whipple’s operation. If partial resection or end-to-end anastomosis of the jejunum had been more quickly performed instead of a relatively invasive retroperitoneal surgery after confirmation of the tumor location in the jejunum, additional interventions, including massive blood transfusion, would not have been required, and the patient’s clinical outcome would have become better. Based on this experience, in cases 2 and 3, tumors were detected in the jejunum by second-look upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and surgery was performed after confirming their location. In case 3, we could intuitively check the location of endoscope tip in real time by performing fluoroscopy simultaneously with endoscopy. Many endoscopists wonder how far the endoscope tip extends during an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and our experience provide information.

Standard upper gastrointestinal endoscopy may not be needed in cases where enteroscopic procedures, such as push enteroscopy, are available immediately. In some reports, lesions of the small intestine have been diagnosed through an oral approach using a colonoscope or pediatric colonoscope[25,26]. However, pediatric colonoscopes are often not available in hospitals that do not perform endoscopy frequently for pediatric patients, and an oral approach using a conventional colonoscope can cause discomfort to patients. In a previous report, there were no adverse effects when the upper gastrointestinal endoscope was inserted deep into the duodenum to the fourth part compared with insertion to the second part, and in our case, there were no adverse effects related to deep insertion[27]. Meticulous re-examination by standard upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is usually recommended in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. In some cases, efforts to maximally insert an endoscope during re-examination by standard upper gastrointestinal endoscopy may be safe and effective for the detection of lesions in the proximal part of the jejunum. As advantages, this standard endoscopy could enable collection of biopsy specimens and perform immediate treatment of bleeding lesions; thus, it should be conducted before small bowel examinations.

Inserting a standard upper endoscope into the deeper part of the duodenum than the second part can help diagnose some cases of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ergenç M, Turkey; Gao C, China; Iwamuro M, Japan S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Foutch PG, Sawyer R, Sanowski RA. Push-enteroscopy for diagnosis of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:337-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Raju GS, Gerson L, Das A, Lewis B; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute medical position statement on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1694-1696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Arakawa D, Ohmiya N, Nakamura M, Honda W, Shirai O, Itoh A, Hirooka Y, Niwa Y, Maeda O, Ando T, Goto H. Outcome after enteroscopy for patients with obscure GI bleeding: diagnostic comparison between double-balloon endoscopy and videocapsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:866-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jeon SR, Kim JO. Deep enteroscopy: which technique will survive? Clin Endosc. 2013;46:480-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Murphy B, Winter DC, Kavanagh DO. Small Bowel Gastrointestinal Bleeding Diagnosis and Management-A Narrative Review. Front Surg. 2019;6:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bresci G, Parisi G, Bertoni M, Tumino E, Capria A. The role of video capsule endoscopy for evaluating obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: usefulness of early use. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:256-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zaman A, Sheppard B, Katon RM. Total peroral intraoperative enteroscopy for obscure GI bleeding using a dedicated push enteroscope: diagnostic yield and patient outcome. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:506-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Descamps C, Schmit A, Van Gossum A. "Missed" upper gastrointestinal tract lesions may explain "occult" bleeding. Endoscopy. 1999;31:452-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kitiyakara T, Selby W. Non-small-bowel lesions detected by capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:234-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Gurudu SR, Bruining DH, Acosta RD, Eloubeidi MA, Faulx AL, Khashab MA, Kothari S, Lightdale JR, Muthusamy VR, Yang J, DeWitt JM. The role of endoscopy in the management of suspected small-bowel bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:22-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gerson LB, Fidler JL, Cave DR, Leighton JA. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Small Bowel Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1265-87; quiz 1288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 448] [Article Influence: 44.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Chak A, Cooper GS, Canto MI, Pollack BJ, Sivak MV Jr. Enteroscopy for the initial evaluation of iron deficiency. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:144-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fry LC, Bellutti M, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P, Mönkemüller K. Incidence of bleeding lesions within reach of conventional upper and lower endoscopes in patients undergoing double-balloon enteroscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:342-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimäki J, Nishida T, Steigen SE, Brabec P, Plank L, Nilsson B, Cirilli C, Braconi C, Bordoni A, Magnusson MK, Linke Z, Sufliarsky J, Federico M, Jonasson JG, Dei Tos AP, Rutkowski P. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:265-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 576] [Cited by in RCA: 672] [Article Influence: 48.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhou L, Liao Y, Wu J, Yang J, Zhang H, Wang X, Sun S. Small bowel gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a retrospective study of 32 cases at a single center and review of the literature. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:1467-1481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nakatani M, Fujiwara Y, Nagami Y, Sugimori S, Kameda N, Machida H, Okazaki H, Yamagami H, Tanigawa T, Watanabe K, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Noda E, Maeda K, Ohsawa M, Wakasa K, Hirakawa K, Arakawa T. The usefulness of double-balloon enteroscopy in gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the small bowel with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Intern Med. 2012;51:2675-2682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vij M, Agrawal V, Kumar A, Pandey R. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 121 cases. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2010;29:231-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Marcella C, Shi RH, Sarwar S. Clinical Overview of GIST and Its Latest Management by Endoscopic Resection in Upper GI: A Literature Review. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2018;2018:6864256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lahoti S, Fukami N. The small bowel as a source of gastrointestinal blood loss. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 1999;1:424-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sass DA, Chopra KB, Finkelstein SD, Schauer PR. Jejunal gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a cause of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:214-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Byeon JS, Chung JW, Choi KD, Choi KS, Kim B, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Kim JH. Clinical features predicting the detection of abnormalities by double balloon endoscopy in patients with suspected small bowel bleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1051-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dulic-Lakovic E, Dulic M, Hubner D, Fuchssteiner H, Pachofszky T, Stadler B, Maieron A, Schwaighofer H, Püspök A, Haas T, Gahbauer G, Datz C, Ordubadi P, Holzäpfel A, Gschwantler M; Austrian Dieulafoy-bleeding Study Group. Bleeding Dieulafoy lesions of the small bowel: a systematic study on the epidemiology and efficacy of enteroscopic treatment. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:573-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 23. | Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1466-1478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 827] [Cited by in RCA: 918] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Brady CE 3rd, Stewart DL, DiPalma JA, Clement DJ, Coleman TW, Rugh KS. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy--how far does the endoscope go? Gastrointest Endosc. 1985;31:367-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jung HS, Shim KN, Baik SJ, Ryu KH, Song HJ, Cho YK. A case of bleeding from proximal jejunal GIST diagnosed by colonoscopy through the oral approach. Korean Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2007;219-222. |

| 26. | Parker HW, Agayoff JD. Enteroscopy and small bowel biopsy utilizing a peroral colonoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:139-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |