Published online Feb 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i4.852

Peer-review started: August 12, 2022

First decision: October 21, 2022

Revised: November 28, 2022

Accepted: January 9, 2023

Article in press: January 9, 2023

Published online: February 6, 2023

Processing time: 177 Days and 23.2 Hours

Abdominal Clostridium perfringens (C. perfringens) gas gangrene is a rare infection that has been described in the literature as most frequently occurring in posto

A 54-year-old male suffered multiple intestinal tears and necrosis after sustaining an injury caused by falling from a high height. These injuries and the subsequent necrosis resulted in intra-abdominal C. perfringens infection. In the first operation, we removed the necrotic intestinal segment, kept the abdomen open and covered the intestine with a Bogota bag. A vacuum sealing drainage system was used to cover the outer layer of the Bogota bag, and the drainage was flushed under negative pressure. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for sup

When the intestines rupture leading to contamination of the abdominal cavity by intestinal contents, C. perfringens bacteria normally present in the intestinal tract may proliferate in large numbers and lead to intra-abdominal infection. Prompt surgical intervention, adequate drainage, appropriate antibiotic therapy, and intensive supportive care comprise the most effective treatment strategy. If the abdominal cavity is heavily contaminated, an open abdominal approach may be a beneficial treatment.

Core Tip: Intra-abdominal gas gangrene caused by closed abdominal injury is extremely rare. When using laparotomy and vacuum sealed drainage combined with intensive care and antibiotic treatment, patients passed the perioperative period smoothly. The diagnosis and treatment of this case is of guiding clinical significance.

- Citation: Li HY, Wang ZX, Wang JC, Zhang XD. Clostridium perfringens gas gangrene caused by closed abdominal injury: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(4): 852-858

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i4/852.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i4.852

Gas gangrene is a serious infection caused by Clostridium spp., which can be divided into Clostridium perfringens (C. perfringens), Clostridium sordelli, Clostridium novyi, and Clostridium putrificum. It occurs more frequently in skin and soft tissue infections. The first case of gas gangrene in a solid organ was reported by Fraenkel in 1881.

Generally, gas gangrene can be classified into three types: Posttraumatic, postoperative, and spontaneous[1]. Both in the past and at present, trauma caused by war and natural disasters has been the main cause of gas gangrene[2-4]. Postoperative gas gangrene has been reported in hilar cholangiocarcinoma, duodenal papillary carcinoma, bladder cancer, cholecystectomy, and even after implant removal[1,5-8]. Spontaneous gas gangrene is commonly seen in immunosuppressed patients, including those with diabetes, tumors, chemotherapy, and ulcerative colitis[9-14]. Gas gangrene has also been observed after colonoscopy, and in the setting of intrapartum drug abuse. Uterine gangrene caused by endometrial cancer, gas gangrene after intramuscular injection[15-19], and even spontaneous abdominal gas gangrene[20] have also been reported. However, intra-abdominal gas gangrene infection after closed abdominal trauma is extremely rare[21].

Cline and Turnbull summarized the symptoms of superficial gas gangrene[3,22], and its diagnosis is relatively simple. The symptoms of uterine gas gangrene have also been summarized[5,7,8]. Because abdominal gas gangrene is difficult to diagnose due to the lack of specific symptoms, it is rarely diagnosed preoperatively and thus carries a high mortality risk. For patients diagnosed with abdominal gas gangrene, very few can be treated conservatively, and timely surgical intervention is usually necessary to reduce the risk of death[3,22-24].

In the past, an open abdominal approach (open abdomen) has been used to treat severe abdominal infection and abdominal compartment syndrome, and vacuum sealing drainage (VSD) was generally only used to treat trunk and extremity infections. Here, we present a case of intra-abdominal gas gangrene following intestinal laceration caused by closed abdominal injury. In this case, we used open abdomen and VSD together as a comprehensive treatment for severe intra-abdominal gas gangrene infection.

A 54-year-old male presented to the emergency department with complaints of “lower back pain, abdominal pain, and extreme abdominal distension for 24 h after falling from height”.

Twenty-four hours before presenting to the emergency department, the patient fell from a height of approximately 3 meters causing lower back pain, and was treated in another hospital. An X-ray showed 12 thoracic vertebral compression fractures. After hospitalization, the patient experienced unbearable severe abdominal distension and abdominal pain and was transferred to our hospital for escalation of care.

The patient had no relevant surgical or medical history.

The patient had no relevant family medical history.

Temperature 36 °C, blood pressure 85/60 mmHg, respiration rate 30 breaths per minute, heart rate 145 beats per minute, blurred consciousness, flat abdomen, abdominal rigidity, obvious abdominal tenderness with rebound, absent liver dullness, and absent bowel sounds.

A complete blood analysis was performed with the following pertinent results: White blood cell count 4800/mm3; neutrophils 75.3%; hemoglobin 143 g/L; C-reactive protein 130 mg/L; Po2 54.5 mmHg; and Pco2 26 mmHg.

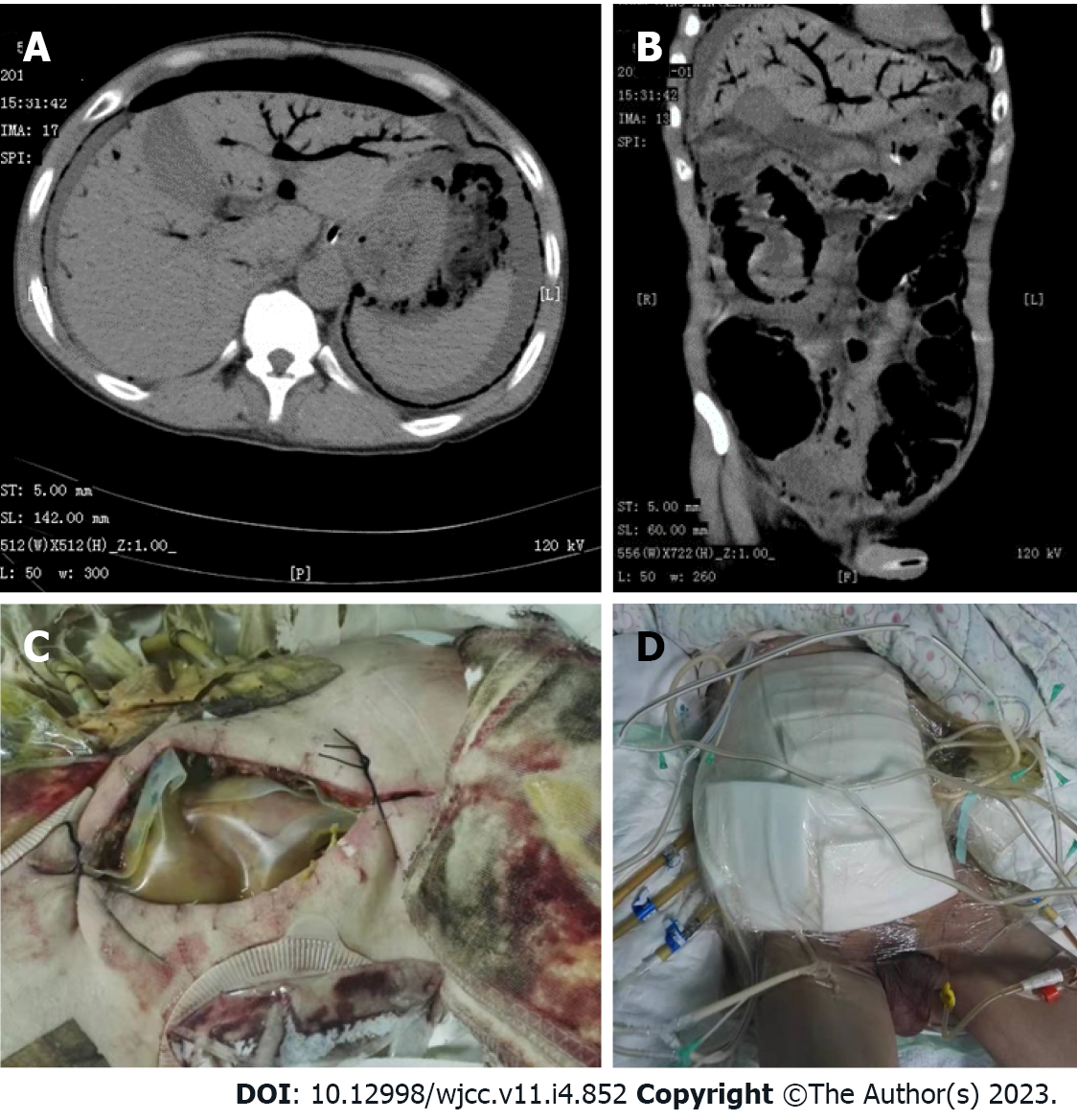

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed pneumoperitoneum, ascites, and portal venous gas (Figure 1A and B).

A large number of Gram-positive bacilli were found in the abdominal pus smear, and the results of bacterial identification by gas chromatography and culture of the pus were consistent with C. perfringens infection. The patient was diagnosed with closed abdominal injury complicated by intestinal necrosis and gas gangrene.

After aggressive fluid resuscitation, emergency laparotomy was performed. A large amount of foul-smelling gas was released during laparotomy, and there were 1.5 L of purulent liquid in the abdominal cavity. The jejunum was transected 100 cm away from the ligament of Treitz, and a length of approximately 40 cm from the upper end was necrotic. The remaining intestine demonstrated multiple contusions. The left colon showed necrosis and a large amount of gas could be seen in the intestinal wall. Crepitus and snowball crepitation were also obvious between the greater omentum layers. The necrotic small intestine and left colon were removed, and transverse colostomy and upper jejunostomy were performed. The abdomen was kept open, the intestine was covered with a Bogota bag, and a gap was left in the middle to facilitate drainage. A VSD device was used to cover the outer layer of the Bogota bag and flush the drainage under negative pressure (Figure 1C and D). After the operation, the patient was transferred to the ICU negative pressure ward, strictly isolated in a single room, and intubated and started on mechanical ventilation. The patient was given 8 million U penicillin, 3 times/d, as well as sulperazon as antibiotic treatment. Colonies of C. perfringens were found to be sensitive to penicillin G, ampicillin, rifampicin, levofloxacin, linezolid, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, cefepime, and cefazolin and resistant to teicoplanin, vancomycin, erythromycin, and clindamycin.

On postoperative day (POD) 6, intestinal contents were found in the abdominal drainage tube. Exploratory reoperation revealed ileal necrosis and a perforation 100 cm away from the ileocecal part and multiple lamellar necrosis of the transverse colon. However, the colon was not perforated. Because the intestinal loop was uncultivated, we repaired the seromuscular layer of the transverse colon at the necrotic mucosa. The transverse colon necrosis was repaired and terminal ileostomy was performed. On POD 10, jejunal necrosis and perforations were found 150 cm from the ligament of Treitz. Debridement and drainage were adopted, and the abdomen was kept open. The bacteria cultured for 3 consecutive days were Escherichia coli rather than C. perfringens. Accordingly, the antibiotics were changed, and the patient was released from isolation. On POD 12, the patient was removed from the ventilator, and enteral nutrition was restored. On POD 20, fascial closure was performed. We summarize the timeline of information from this case report in Table 1.

| Date | Time | Major event | Treatment |

| 3/31/2017 | - | Fall from a high height | Admitted to another hospital |

| 4/1/2017 | - | Severe abdominal distension and unbearable abdominal pain | Transferred to our hospital |

| 14:30 | Shock | Anti-shock therapy | |

| 18:00 | Abdominal CT showed pneumoperitoneum, ascites and portal venous gas | Emergency laparotomy | |

| 18:00-23:50 | First operation; crepitus and snow-ball crepitation were obvious between the greater omentum layers | Intraoperative bacterial smear; ICU life support after surgery | |

| 4/2/2017 | 1:00 | Suspected gas gangrene | Antibiotic therapy with penicillin, sulperazon and ornidazole |

| 1:20 | Critical values in coagulation tests were reported | Plasma transfusion | |

| 10:00 | A large number of Gram-positive bacilli found in pus smear | Open abdomen | |

| 4/3/2017 | 7:30 | Critical values in coagulation tests were reported | Plasma transfusion |

| 4/4/2017 | 10:00 | Clostridium perfringens cultured in drainage fluid | Continued antibiotic therapy |

| 4/7/2017 | 9:00 | Intestinal contents were found in abdominal drainage fluid | Second operation |

| 4/11/2017 | 9:00 | Multidrug-resistant bacteria were found in sputum culture | Added imipenem to antibiotic therapy |

| 10:00 | Clostridium perfringens culture negative | - | |

| 12:00 | Intestinal contents found in abdominal drainage fluid | Third operation | |

| 4/12/2017 | 10:00 | Clostridium perfringens culture negative; patient regained consciousness | - |

| 4/13/2017 | 10:00 | Clostridium perfringens culture negative; restored enteral nutrition; SBT experiment implemented | Discontinued penicillin; extubated |

| 4/14/2017 | 10:00 | Enterococcus faecium found in sputum culture | Replaced other antibiotics with vancomycin |

| 4/21/2017 | 15:30 | Fascial closure | - |

| 4/24/2017 | 15:00 | Patient transferred to general ward | Antibiotics downgraded to Cefoxitin |

| 4/27/2017 | 10:00 | Escherichia coli cultured from peritoneal drainage fluid | Antibiotics replaced with sulperazon and amikacin |

| 5/1/2017 | 10:00 | Patient able to move with protective gear | Removed abdominal drainage tube |

| 5/12/2017 | 10:00 | Patient discharged | - |

| 5/30/2017 | - | Patient developed progressive myasthenia | Diagnosed with Guillain-Barre syndrome |

| 6/14/2017 | - | Patient died of respiratory failure | - |

The patient was able to move with protective gear 30 d after the operation and was discharged after recovery. Unfortunately, 3 wk after discharge, the patient developed limb weakness, which worsened progressively, and was hospitalized again. After admission, nutrition improved but the patient had difficulty breathing. He was transferred to the ICU again and restarted on mechanical ventilation to assist breathing. Electromyography demonstrated widespread nerve damage throughout the body. Lumbar puncture revealed normal cerebrospinal fluid pressure. Routine tests of cerebrospinal fluid showed that the number of cells was 7/L, and biochemical tests showed that the protein level was 2734 mg/L The department of neurology was consulted to consider Guillain-Barre syndrome after trauma and severe infection. The patient’s muscle strength did not recover significantly after methylprednisolone pulse therapy. Seven days later, the patient and his family asked to discontinue treatment. On POD 75, he died of respiratory failure.

C. perfringens spores are widely distributed in nature, routinely found on clothing, and known to colonize the biliary, intestinal, and female reproductive tracts[22]. If there is an appropriate growth environment, such as in the settings of closed abdominal trauma or abdominal tissue or organ ischemia and necrosis, C. perfringens bacteria in the intestine will multiply in large numbers and may lead to intra-abdominal gas gangrene infection.

The diagnosis of abdominal organ gas gangrene is based on the symptoms described in uterine gas gangrene; however, in the case of abdominal organ gas gangrene, Gram-positive bacteria would be found in peritoneal fluid rather than vaginal secretions. X-ray is useful for the diagnosis of soft tissue gas gangrene but is limited to the abdomen[4]; CT and magnetic resonance (MR) methods can clearly illustrate the presence of interstitial gas, with MR taking longer[4,11]. Portal venous gas was once an indicator of poor prognosis[5,25]. With the advancement of imaging technologies, mortality has decreased significantly. In any case, the presence of gas in solid organs and walls of hollow organs is abnormal and should be considered red flags[26]. Surgical exploration is the main method for follow-up of gas in organs discovered by imaging. If the gas and liquid in the abdominal cavity are foul-smelling and accompanied by gas accumulation in the tissue space and obvious snowball crepitation, gas gangrene infection should be suspected. Bacterial culture of C. perfringens from paracentesis fluid or pus is the definitive method of diagnosis, but the positive rate is not high[2,4]. In our case described above, C. perfringens was cultured from peritoneal drainage fluid.

For patients who are diagnosed with intra-abdominal gas gangrene, the removal of necrotic tissue and effective drainage are both key to successful treatment. Open abdomen, although controversial for the treatment of severe abdominal infection, is part of the damage control strategy and is considered beneficial[27-29]. Temporary closure of the abdominal cavity and the use of VSD meet the requirements of negative pressure therapy[12,19,30] and can be applied to the open abdomen until the requirements of abdominal fascia closure are met[28,29,31,32]. Negative pressure drainage in the treatment of soft tissue gas gangrene has also been reported[31]. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is also recommended for the treatment of gas gangrene[3,4,22], but was not used in our case. To our knowledge, we are the first to successfully apply the open abdominal approach and Bogota bag with VSD in the treatment of intra-abdominal gas gangrene.

The use of antibiotics is critical, and penicillin is the first choice. Although some experiments have proven that clindamycin is more active than penicillin in experimental gas gangrene[3,22,33,34], other broad-spectrum antibiotics should be used in combination to treat possible concurrent infections, and empirical drugs are also recommended before diagnosis[4,34]. Appropriate antibiotics should not be selected until the drug susceptibility results are obtained. In the case above, the patient was resistant to clindamycin.

Closed abdominal injury may cause intra-abdominal gas gangrene infection. Timely diagnosis, surgery, and appropriate antibiotic therapy are keys to treatment, and intensive care is necessary. If the abdominal cavity is heavily contaminated, open abdomen is a beneficial treatment.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Demetrashvili Z, Georgia; Musa Y, Canada; Palacios Huatuco RM, Argentina S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Bergert H, Illert T, Friedrich K, Ockert D. Fulminant liver failure following infection by Clostridium perfringens. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2004;5:205-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chen E, Deng L, Liu Z, Zhu X, Chen X, Tang H. Management of gas gangrene in Wenchuan earthquake victims. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2011;31:83-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stevens DL, Aldape MJ, Bryant AE. Life-threatening clostridial infections. Anaerobe. 2012;18:254-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Leiblein M, Wagner N, Adam EH, Frank J, Marzi I, Nau C. Clostridial Gas Gangrene - A Rare but Deadly Infection: Case series and Comparison to Other Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections. Orthop Surg. 2020;12:1733-1747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Miyata Y, Kashiwagi H, Koizumi K, Kawachi J, Kudo M, Teshima S, Isogai N, Miyake K, Shimoyama R, Fukai R, Ogino H. Fatal liver gas gangrene after biliary surgery. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;39:5-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Takazawa T, Ohta J, Horiuchi T, Hinohara H, Kunimoto F, Saito S. A case of acute onset postoperative gas gangrene caused by Clostridium perfringens. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Qandeel H, Abudeeb H, Hammad A, Ray C, Sajid M, Mahmud S. Clostridium perfringens sepsis and liver abscess following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Surg Case Rep. 2012;2012:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang S, Liu L. Gas gangrene following implant removal after the union of a tibial plateau fracture: a case report. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gray KM, Padilla PL, Sparks B, Dziewulski P. Distant myonecrosis by atraumatic Clostridium septicum infection in a patient with metastatic breast cancer. IDCases. 2020;20:e00784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Akagawa M, Kobayashi T, Miyakoshi N, Abe E, Abe T, Kikuchi K, Shimada Y. Vertebral osteomyelitis and epidural abscess caused by gas gangrene presenting with complete paraplegia: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dontchos BN, Ricca R, Meehan JJ, Swanson JO. Spontaneous Clostridium perfringens myonecrosis: Case report, radiologic findings, and literature review. Radiol Case Rep. 2013;8:806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ball CG, Ouellet JF, Anderson IB, Kirkpatrick AW. Avoidance of total abdominal wall loss despite torso soft tissue clostridial myonecrosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kiel N, Ho V, Pascoe A. A case of gas gangrene in an immunosuppressed Crohn's patient. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3856-3858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nanjappa S, Shah S, Pabbathi S. Clostridium septicum Gas Gangrene in Colon Cancer: Importance of Early Diagnosis. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2015;2015:694247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fairley LJ, Smith SL, Fairley SK. A case report of iatrogenic gas gangrene post colonoscopy successfully treated with conservative management- is surgery always necessary? BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | De Angelis B, Cerulli P, Lucilla L, Fusco A, Di Pasquali C, Bocchini I, Orlandi F, Agovino A, Cervelli V. Spontaneous clostridial myonecrosis after pregnancy - emergency treatment to the limb salvage and functional recovery: a case report. Int Wound J. 2014;11:93-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kashan D, Muthu N, Chaucer B, Davalos F, Bernstein M, Chendrasekhar A. Uterine Perforation with Intra-Abdominal Clostridium perfringens Gas Gangrene: A Rare and Fatal Infection. J Gynecol Surg. 2016;32:182-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Paquier L, Mihanović J, Counil A, Karlo R, Bačić I, Dželalija B. Extensive clostridial myonecrosis after gluteal intramuscular injection in immunocompromised patient treated with surgical debridement and negative-pressure wound therapy. Trauma Case Rep. 2021;32:100469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wion D, Le Bert M, Brachet P. Messenger RNAs of beta-amyloid precursor protein and prion protein are regulated by nerve growth factor in PC12 cells. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1988;6:387-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhen BL. Abdominal wall gas gangrene caused by closed small intestinal injury: a case report. Qinghai Yixue Zazhi. 1987;6:55. |

| 22. | Cline KA, Turnbull TL. Clostridial myonecrosis. Ann Emerg Med. 1985;14:459-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | MacLennan JD, MacFarlane RG. Toxin and antitoxin studies of gas gangrene in man. Lancet. 1945;246:301-305. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Potts WJ. Battle Casualties in a South Pacific Evacuation Hospital. Ann Surg. 1944;120:886-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Alqahtani S, Coffin CS, Burak K, Chen F, MacGregor J, Beck P. Hepatic portal venous gas: a report of two cases and a review of the epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and approach to management. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:309-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nepal P, Ojili V, Kaur N, Tirumani SH, Nagar A. Gas Where It Shouldn't Be! AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:812-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Robledo FA, Luque-de-León E, Suárez R, Sánchez P, de-la-Fuente M, Vargas A, Mier J. Open versus closed management of the abdomen in the surgical treatment of severe secondary peritonitis: a randomized clinical trial. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2007;8:63-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kirkpatrick AW, Coccolini F, Ansaloni L, Roberts DJ, Tolonen M, McKee JL, Leppaniemi A, Faris P, Doig CJ, Catena F, Fabian T, Jenne CN, Chiara O, Kubes P, Manns B, Kluger Y, Fraga GP, Pereira BM, Diaz JJ, Sugrue M, Moore EE, Ren J, Ball CG, Coimbra R, Balogh ZJ, Abu-Zidan FM, Dixon E, Biffl W, MacLean A, Ball I, Drover J, McBeth PB, Posadas-Calleja JG, Parry NG, Di Saverio S, Ordonez CA, Xiao J, Sartelli M; Closed Or Open after Laparotomy (COOL) after Source Control for Severe Complicated Intra-Abdominal Sepsis Investigators. Closed Or Open after Source Control Laparotomy for Severe Complicated Intra-Abdominal Sepsis (the COOL trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sharafuddin MJ, Kresowik TF. Commentary. Pawaskar M, Satiani B, Balkrishnan R, Starr JE. Economic evaluation of carotid artery stenting versus carotid endarterectomy for the treatment of carotid artery stenosis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:413-419. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2008;20:385-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Coccolini F, Roberts D, Ansaloni L, Ivatury R, Gamberini E, Kluger Y, Moore EE, Coimbra R, Kirkpatrick AW, Pereira BM, Montori G, Ceresoli M, Abu-Zidan FM, Sartelli M, Velmahos G, Fraga GP, Leppaniemi A, Tolonen M, Galante J, Razek T, Maier R, Bala M, Sakakushev B, Khokha V, Malbrain M, Agnoletti V, Peitzman A, Demetrashvili Z, Sugrue M, Di Saverio S, Martzi I, Soreide K, Biffl W, Ferrada P, Parry N, Montravers P, Melotti RM, Salvetti F, Valetti TM, Scalea T, Chiara O, Cimbanassi S, Kashuk JL, Larrea M, Hernandez JAM, Lin HF, Chirica M, Arvieux C, Bing C, Horer T, De Simone B, Masiakos P, Reva V, DeAngelis N, Kike K, Balogh ZJ, Fugazzola P, Tomasoni M, Latifi R, Naidoo N, Weber D, Handolin L, Inaba K, Hecker A, Kuo-Ching Y, Ordoñez CA, Rizoli S, Gomes CA, De Moya M, Wani I, Mefire AC, Boffard K, Napolitano L, Catena F. The open abdomen in trauma and non-trauma patients: WSES guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Liu Z, Zhao D, Wang B. Improved vacuum sealing drainage in the treatment of gas gangrene: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:19626-19628. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Huang Q, Li J, Lau WY. Techniques for Abdominal Wall Closure after Damage Control Laparotomy: From Temporary Abdominal Closure to Early/Delayed Fascial Closure-A Review. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:2073260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Stevens DL, Maier KA, Laine BM, Mitten JE. Comparison of clindamycin, rifampin, tetracycline, metronidazole, and penicillin for efficacy in prevention of experimental gas gangrene due to Clostridium perfringens. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:220-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Aldape MJ, Bayer CR, Rice SN, Bryant AE, Stevens DL. Comparative efficacy of antibiotics in treating experimental Clostridium septicum infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;52:469-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |