Published online Dec 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i36.8498

Peer-review started: October 12, 2023

First decision: November 28, 2023

Revised: November 29, 2023

Accepted: December 5, 2023

Article in press: December 5, 2023

Published online: December 26, 2023

Processing time: 71 Days and 7.1 Hours

The effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) on the mortality of patients with sepsis is not well characterized.

To elucidate the association between prior ACEI or ARB exposure and mortality in sepsis.

The PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases were searched for all studies of premorbid ACEI or ARB use and sepsis mortality until November 30 2019. Two reviewers independently assessed, selected, and ab

A total of six studies comprising 281238 patients with sepsis, including 49799 cases with premorbid ACEI or ARB exposure were eligible for analysis. Pre

The results of this systematic review suggest that ACEI or ARB exposure prior to sepsis may be associated with reduced mortality. Further high-quality cohort studies and molecular mechanism experiments are required to confirm our results.

Core Tip: To explore the potential relationship between the effect of premorbid angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) on mortality in sepsis. We extracted data from 6 studies. The results of this systematic review suggest that ACEI or ARB exposure prior to sepsis may be associated with reduced mortality. This may have some guiding significance for the treatment of coronavirus disease 2019.

- Citation: Yang DC, Xu J, Jian L, Yu Y. Impact of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers on the mortality in sepsis: A meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(36): 8498-8506

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i36/8498.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i36.8498

Sepsis is a syndrome that involves physiological, pathological, and biochemical abnormalities resulting from a host response to an infection, and represents a major public health concern[1]. Sepsis is a "worldwide medical problem" that endangers human health and is associated with three main characteristics: (1) High incidence; (2) high mortality; and (3) high treatment cost. More than 19 million people suffer from sepsis every year worldwide, with a fatality rate greater than 25%[2].

As sepsis progresses after an infection, an imbalance of the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory response develops[3]. The guidelines associated with development of the sepsis pathophysiology suggest: Early fluid resuscitation, antibiotic treatment, control of infection sources, use of vasoactive agents, corticosteroids, blood products, immunoglobulins, blood purification as treatment options[2]. Although the guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of sepsis have been revised several times, the monitoring index does not fully reflect the overall situation and dynamic changes of the patients, treatment is associated with a lag period, and the mortality rate remains high[4]. Therefore, it is important to accurately identify potential patients who are at a high risk of sepsis and to take specific intervention measures to reduce the mortality of such patients. Such supplement to the previous treatment programs and may improve the prognosis of sepsis patients.

Several studies have suggested that the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) may represent a therapeutic option for patients with sepsis[5,6]. Moreover, ACEIs and ARBs have been shown to exert anti-inflammatory effects to attenuate the chronic inflammation[7]. However, the benefit of using ACE inhibitors or ARBs remains controversial[5,8]. Moreover, there are no published systematic reviews on the effects of premorbid ACEI or ARB exposure on sepsis mortality. Thus, this study sought to investigate sepsis mortality in patients with prior ACEI and ARB exposure.

This study followed the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines[9]. A literature search of relevant published studies that analyzed the association between the sepsis, mortality, and ACEIs or ABBs was conducted on 27 March 2020. We used the PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), EMBASE (http://www.embase.com/), Web of Science (http://wokinfo.com/), and Cochrane Library (http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/) databases to identify articles using the following terms: “hypotensor”; “antihypertensive”; “ACEIs”; “captopril”; “enalapril”; “sirapley”; “benazepril”; “petitopril”; “ramipril”; “ARBs”; “losartan”; “irbesartan”; “valsartan”; “telmisartan”; “sepsis”; “toxic shock”; “sepsis shock”; and “mortality”. In addition, the reference lists in each of the studies were reviewed to identify additional studies. The language of the studies was limited to English, and we did not search for unpublished literature.

A study was included in the analysis if: (1) It was a case-control or cohort study was conducted; (2) it was an original human clinical trial (independence among studies) that evaluated the association between premorbid ACEI or ARB exposure and sepsis mortality; and (3) it provided sufficient data [e.g., to calculate the relative risk (RR), odds ratio (OR), or hazard ratio (HR)]; and (4) the (Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, NOS) score value was ≥ 5. We excluded studies that contained overlapping data.

The data extracted from the selected articles included: the first author’s name; year of publication; study population; total number of cases; RRs or ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs); Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS); and adjustments made in the studies (Table 1). Some publications separate reported ORs for ACEI-related sepsis mortality and ARB-related sepsis mortality. In these cases, the ORs were separately extracted.

| Ref. | Population and country | No. of cases | Study type | Adjustment OR (95%CI) | Adjustment | NOS |

| Mortensen EM et al[15], 2007 | 3018; United States | 547 | Cohort | ARBs: 0.42 (0.24-0.76) | Age, history of myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, chronic lung disease, dementia, and moderate liver disease | 6 |

| Dial et al[16], 2014 | 21615; United Kingdom | 1965 | Cohort | ACEIs: 1.93 (1.56-2.40) | Age, gender, BMI, ever smoking, blood pressure, alcohol abuse, comorbidity, medication | 7 |

| ARBs: 0.91(0.61-1.37) | ||||||

| Wiewel et al[17], 2017 | 6994; Netherlands | 1483 | Cohort | ACEIs/ARBs: 1.27 (0.88-1.84) | Age, gender, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation IV score, race, weight, comorbidity and medication | 7 |

| Kim et al[18], 2019 | 4549; South Korea | 673 | Cohort | ACEIs/ARBs: 1.32 (1.11-1.56) | Age, gender, comorbidity (heart failure, ischemic heart disease, asthma, chronic renal disease, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, and solid tumor) | 7 |

| Lai et al[19], 2019 | 21502; China | 11918 | Cohort | ACEIs/ARBs: 1.31 (1.22-1.40) | Age, gender, comorbidities, medication | 7 |

| Hsieh et al[20], 2020 | 223560; China | 33213 | Cohort | ACEIs: 0.93 (0.88-0.98) | Age, gender, insurance premium, urbanization level and comorbidity | 6 |

| ARBs: 0.85 (0.81-0.90) |

The strength of the association between premorbid ACEI or ARB exposure and susceptibility to sepsis mortality was reported using ORs and 95%CIs. ACEIs or ARBs were defined as captopril, enalapril, benazepril, fosinopril, ramipril, losartan, valsartan, and candesartan. When the data was adjusted and crude ORs were provided, the most adjusted ORs were extracted. If the article provided an HR, it was converted to an OR using the appropriate formula[10]. We used an I2 test and Q-statistic to detect any possible heterogeneity between the studies, as a quantitative measure of any inconsistencies among the studies[11]. In addition, we clarified the percentage of the total variation across the studies that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance using the I2-statistic. Pooled ORs and 95%CIs were calculated using a random-effects model[12].

All statistical analyses for the meta-analysis were performed using STATA version 12.0 (United States, College Station, TX 77845). Statistical significance was established at a threshold of P ≤ 0.05. All reported P values were obtained from two-sided statistical tests. Egger’s and Begger’s regression models were used to evaluate the potential publication bias[11].

The process used to select the studies for analysis is outlined in Figure 1. A total of 48 potentially relevant records were reviewed, of which six articles, which included 49799 cases that met the inclusion criteria were included in the meta-analysis[5,8,13-16] (Table 1). A total of 42 studies were subsequently excluded because they used a combined inter

Three studies were conducted in Asia and three studies were conducted in other regions (Europe and America). Two studies presented the mortality separately for ACEIs and ARBs. The NOS was 7 and 6 in four and two studies, re

| Group | No. of studies | OR (95%CI) | Pheterogeneity | I2 (%) |

| Geographic area | ||||

| Non-Asia | 4 | 0.91 (0.74-1.09) | 0 | 94.6 |

| Asia | 4 | 0.94 (0.91-0.98) | 0 | 96.7 |

| Object | ||||

| ACEIs | 2 | 0.94 (0.89-0.99) | < 0.01 | 95.3 |

| ARBs | 3 | 0.84 (0.79-0.88) | 0.006 | 80.7 |

| ACEIs/ARBs | 3 | 1.31 (1.23-1.39) | 0.983 | 0 |

| NOS | ||||

| 6 | 3 | 0.88 (0.85-0.91) | 0 | 88.6 |

| 7 | 5 | 1.31 (1.24-1.39) | 0.013 | 68.4 |

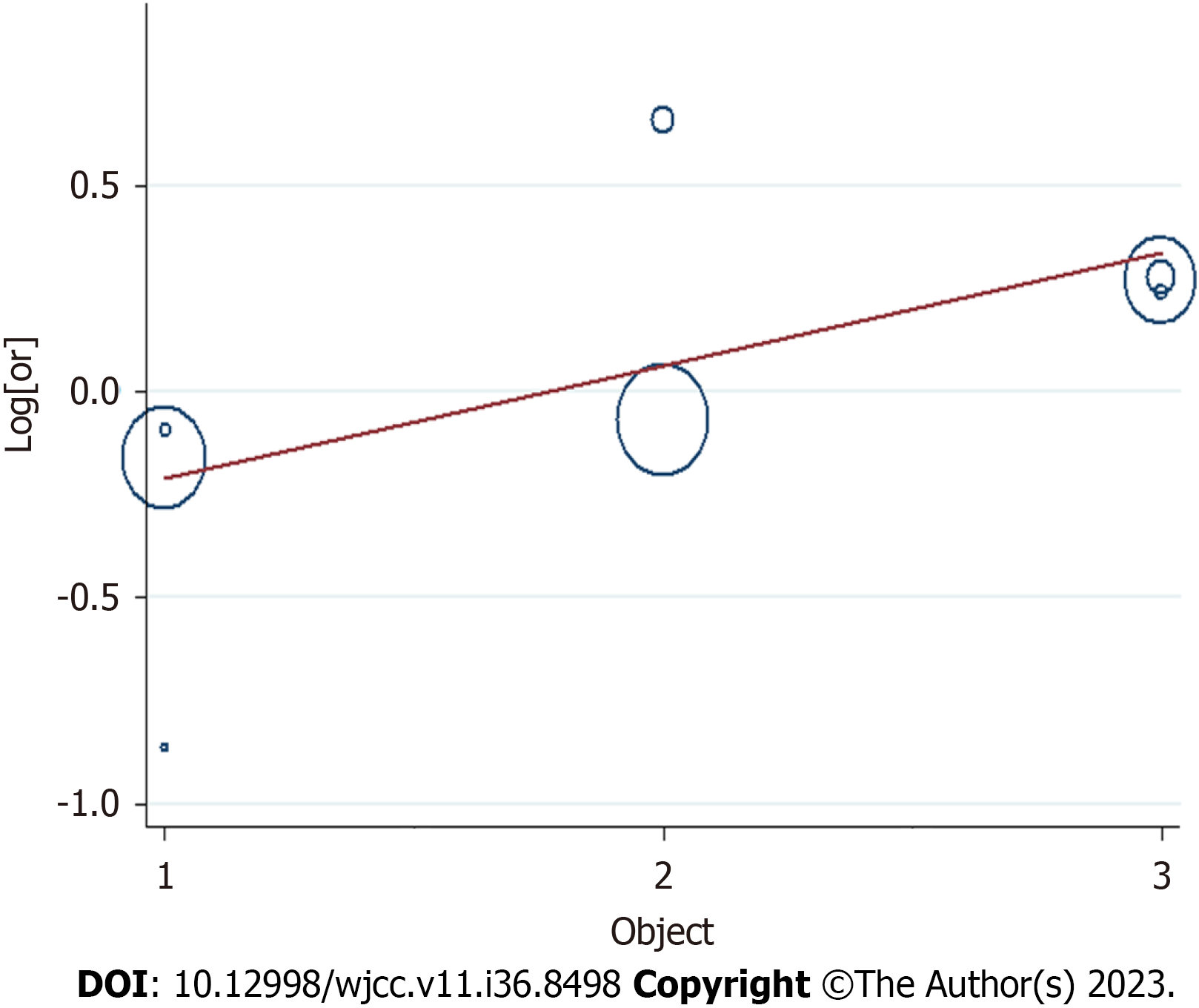

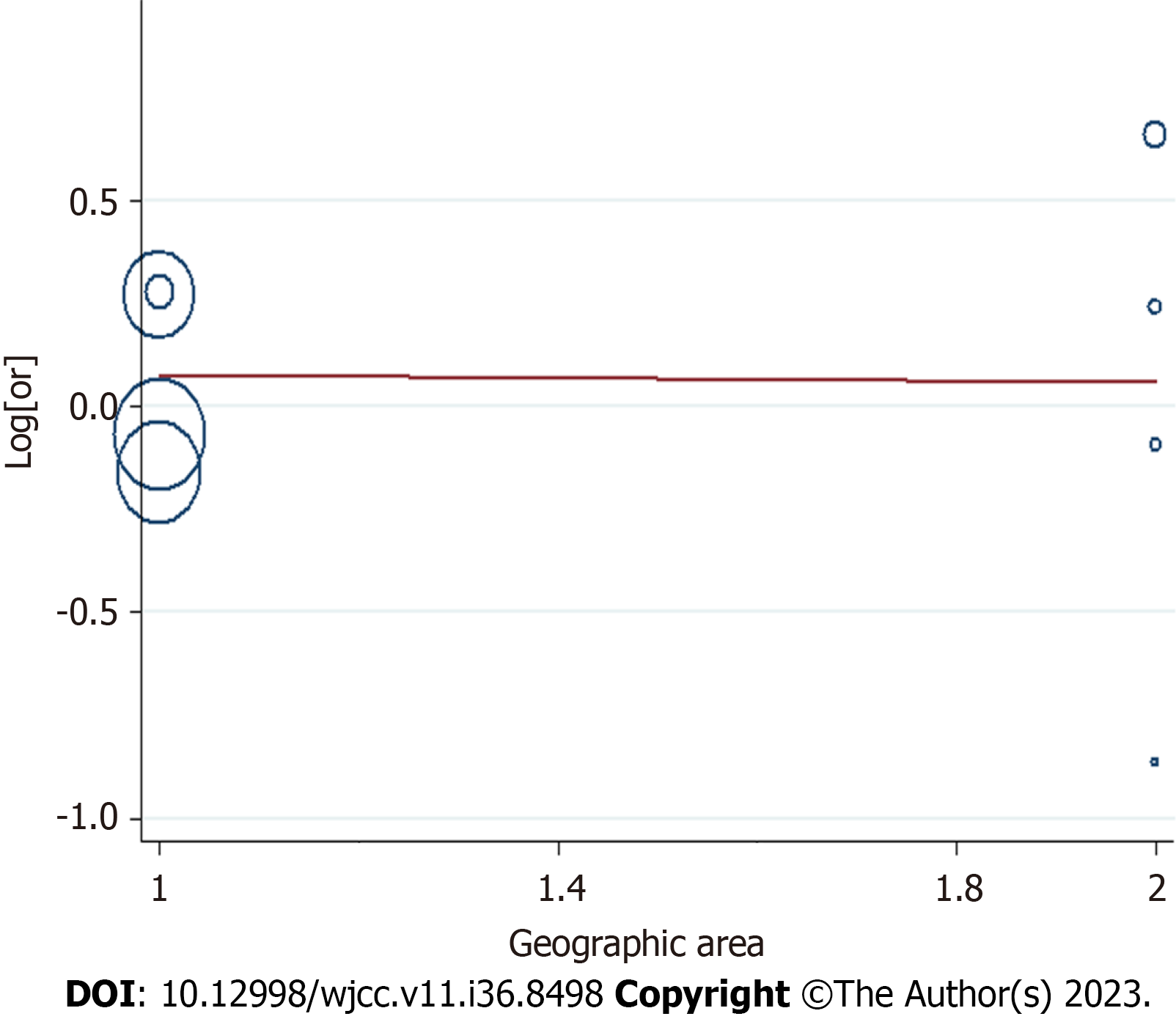

Due to differences in the geographic area (Asian or non-Asian countries), NOS (7 or 6), and prior exposure (ACEIs, ARBs, and ACEIs/ARBs) between the studies, we conducted further subgroup analyses to determine the effect of these factors in our analyses (Table 2). We obtained a statistically protective effect in Asian population (OR: 0.94; 95%CI: 0.91–0.98), ACEIs (OR: 0.94, 95%CI: 0.89–0.99), ARBs (OR: 0.84, 95%CI: 0.79 – 0.88), NOS of 6 (OR: 0.88; 95%CI: 0.85–0.91), in a non-Asian population (OR: 0.91; 95%CI: 0.74–1.09), NOS of 7 (OR: 1.31; 95%CI: 1.24–1.39), and ACEIs/ARBs (OR: 1.31; 95%CI: 1.23–1.39).

Based on Egger’s and Begger’s regression models, there was no evidence of publication bias (Figures 5) regarding prior ACEI or ARB exposure and mortality in sepsis. The Egger’s funnel plot and Begger linear regression test revealed a P value > 0.05.

This is the first systematic review examining the role of premorbid ACEI or ARB exposure on mortality outcomes in patients with sepsis. Patients receiving ACEIs or ARBs prior to developing sepsis were associated with a 6% reduction in 30-day mortality compared with those who did not receive any ACEIs or ARBs. We further conducted subgroup analyses to determine the effect of the geographic area (Asian or non-Asian countries), NOS (7 or 6), and prior exposure (ACEIs, ARBs, and ACEIs/ARBs) in our analyses (Table 2). We obtained a statistically protective effect in the Asian population (OR: 0.94; 95%CI: 0.91–0.98), ACEIs (OR: 0.94; 95%CI: 0.89–0.99), ARBs (OR: 0.84; 95%CI: 0.79–0.88), and a NOS of 6 (OR: 0.88; 95%CI: 0.85–0.91). The results of a meta-regulation test (Figures 3 and 4) revealed that the geographical area and treatment were associated with 60.62% reduction in heterogeneity across the studies.

One cause of the differences in the outcomes between population may be lifestyle and environmental factors associated with Asian and non-Asian populations[17-19]. Compared with European and American populations, Asian populations have a relatively healthy diet and a lower prevalence of chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes and coronary heart disease)[20-22], which have a substantial impact on the prognosis of sepsis.

ACE inhibitors and ARBs reduce blood pressure by vasodilation, decreasing angiotensin II formation, and kallikrein degradation to reduce sodium and water retention[23]. These effects can also decrease the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) since angiotensin II plays a critical role in the maintenance of GFR, especially during hypovolemia or hypotension[24,25]. In the guidelines for sepsis treatment, the maintenance of a certain tissue perfusion pressure is necessary; however, the use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs appear to be contrary to the recommended treatment guidelines for sepsis. Moreover, ACE inhibitors and ARBs have not been recommended as a therapeutic drug in previous septic diagnosis and treatment guidelines. In addition to the effect of lowering blood pressure, both ACE inhibitors and ARBs also have anti-inflammatory effects, which can reduce plasma cytokine and nitric oxide concentrations[26]. In septic animal models, although ACE inhibitors have been demonstrated to reduce organ damage through the NF-kB signaling pathway[27], conflicting data exist regarding to whether an angiotensin II blockade improves survival in animal models[28,29]. Moreover, a clinical study of patients hospitalized with sepsis reported that the prior use of ARBs was associated with improved survival[8].

Our findings have potential clinical implications. Clinical medical providers should be able to identify who is at a high-risk of sepsis as early as possible and guide the course of treatment following the initial screening. Combined with our meta-analysis, the use of ACEIs or ARBs can improve the prognosis of sepsis patients, and the comparison of the effect of ACEIs and ARBs on the prognosis of sepsis is presently not supported by any data. Therefore, if patients treated with ACEIs cannot tolerate their adverse reactions, they can continue to use ARBs. It is recommended that ACEIs or ARBs be abandoned only if the adverse effects are severely intolerable[30].

This study analyzed data from six observational studies and included a larger population and range of trials compared to that previous studies, with the largest number of cases analyzed to date. We conformed to the specifications through

There are a few limitations regarding this study that should be noted. First, when selecting appropriate literature, only studies written in English were included; however, a large portion of the articles that were included in our study were performed in Asia, where the official language is not English. Second, it was challenging to predict the effect of misclassification of cohort studies for the results. In addition, the systematic confounding or the risk of bias cannot easily be ruled out in observation studies. Since there was heterogeneity across the studies, we performed a regression analysis to explain the source of such heterogeneity. The observed differences may be due to the differences in the geographical area of the studies. Specifically, differences in the study geographical area and prior treatment (ACEIs, ARBs, and ACEIs/ARBs) may have contributed to the heterogeneity observed in our results (Figure 4). Besides, the practice of ACEI and ARB in the clinic are related to disease conditions like hypertension, which might also influence the prognosis of sepsis. Besides, other factors like age may also bring bias. In this analysis, the comparison between the dose and course of treatment of ACEIs or ARBs and the prognosis of sepsis were not included due to the lack of data provided in the original studies.

In summary, the findings of this systematic review suggests that exposure to ACEIs or ARBs prior to an episode of sepsis could have a role in reducing sepsis mortality; however, additional evidence is required to clarify whether premorbid ACEIs or ARBs can reduce sepsis mortality, as well as the associated mechanism. Therefore, further high-quality cohort studies and molecular mechanism experiments are required to confirm our results.

Sepsis is a syndrome that involves physiological, pathological, and biochemical abnormalities resulting from a host response to an infection, and represents a major public health concern.

Therefore, it is important to accurately identify potential patients who are at a high risk of sepsis and to take specific intervention measures to reduce the mortality of such patients. Several studies have suggested that the use of angio

The effect of ACEI or ARB on the mortality of patients with sepsis is not well characterized.

To elucidate the association between prior ACEI or ARB exposure and mortality in sepsis.

This study followed the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines. A literature search of relevant published studies that analyzed the association between the sepsis, mortality, and ACEIs or ABBs was conducted on 27 March 2020. We used the PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), EMBASE (http://www.embase.com/), Web of Science (http://wokinfo.com/), and Cochrane Library (http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/) databases to identify articles using the following terms: “hypotensor”; “antihypertensive”; “ACEIs”; “captopril”; “enalapril”; “sirapley”; “benazepril”; “petitopril”; “ramipril”; “ARBs”; “losartan”; “irbesartan”; “valsartan”; “telmisartan”; “sepsis”; “toxic shock”; “sepsis shock”; and “mortality”. In addition, the reference lists in each of the studies were reviewed to identify additional studies. The language of the studies was limited to English, and we did not search for unpublished literature.

A total of 48 potentially relevant records were reviewed, of which six articles, which included 49799 cases that met the inclusion criteria were included in the meta-analysis. A total of 42 studies were subsequently excluded because they used a combined intervention, were duplicated reports, or were of relatively low quality. All of the six selected articles were cohort studies.

The findings of this systematic review suggests that exposure to ACEIs or ARBs prior to an episode of sepsis could have a role in reducing sepsis mortality.

However, additional evidence is required to clarify whether premorbid ACEIs or ARBs can reduce sepsis mortality, as well as the associated mechanism. Therefore, further high-quality cohort studies and molecular mechanism experiments are required to confirm our results.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, general and internal

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ghimire R, Nepal S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu ZH

| 1. | Liang L, Moore B, Soni A. National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2017. 2020 Jul 14. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006 Feb-. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15803] [Cited by in RCA: 17142] [Article Influence: 1904.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | van der Poll T, van de Veerdonk FL, Scicluna BP, Netea MG. The immunopathology of sepsis and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:407-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 746] [Cited by in RCA: 1208] [Article Influence: 151.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304:1787-1794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1920] [Cited by in RCA: 1781] [Article Influence: 118.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dial S, Nessim SJ, Kezouh A, Benisty J, Suissa S. Antihypertensive agents acting on the renin-angiotensin system and the risk of sepsis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78:1151-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mortensen EM, Nakashima B, Cornell J, Copeland LA, Pugh MJ, Anzueto A, Good C, Restrepo MI, Downs JR, Frei CR, Fine MJ. Population-based study of statins, angiotensin II receptor blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on pneumonia-related outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1466-1473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Podowski M, Calvi C, Metzger S, Misono K, Poonyagariyagorn H, Lopez-Mercado A, Ku T, Lauer T, McGrath-Morrow S, Berger A, Cheadle C, Tuder R, Dietz HC, Mitzner W, Wise R, Neptune E. Angiotensin receptor blockade attenuates cigarette smoke-induced lung injury and rescues lung architecture in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:229-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mortensen EM, Restrepo MI, Copeland LA, Pugh JA, Anzueto A, Cornell JE, Pugh MJ. Impact of previous statin and angiotensin II receptor blocker use on mortality in patients hospitalized with sepsis. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:1619-1626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008-2012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14425] [Cited by in RCA: 16776] [Article Influence: 671.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4738] [Cited by in RCA: 4949] [Article Influence: 274.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10586] [Cited by in RCA: 12172] [Article Influence: 405.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45:139-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1231] [Cited by in RCA: 1917] [Article Influence: 191.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hsieh MS, How CK, Hsieh VC, Chen PC. Preadmission Antihypertensive Drug Use and Sepsis Outcome: Impact of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACEIs) and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs). Shock. 2020;53:407-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lai CC, Wang YH, Wang CY, Wang HC, Yu CJ, Chen L; on the behalf of Taiwan Clinical Trial Consortium for Respiratory Diseases (TCORE). Risk of Sepsis and Mortality Among Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Treated With Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors or Angiotensin Receptor Blockers. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:e14-e20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim J, Kim YA, Hwangbo B, Kim MJ, Cho H, Hwangbo Y, Lee ES. Effect of Antihypertensive Medications on Sepsis-Related Outcomes: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:e386-e393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wiewel MA, van Vught LA, Scicluna BP, Hoogendijk AJ, Frencken JF, Zwinderman AH, Horn J, Cremer OL, Bonten MJ, Schultz MJ, van der Poll T; Molecular Diagnosis and Risk Stratification of Sepsis (MARS) Consortium. Prior Use of Calcium Channel Blockers Is Associated With Decreased Mortality in Critically Ill Patients With Sepsis: A Prospective Observational Study. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:454-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Turana Y, Tengkawan J, Soenarta AA. Asian management of hypertension: Current status, home blood pressure, and specific concerns in Indonesia. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2020;22:483-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Poon LHJ, Yu CP, Peng L, Ewig CL, Zhang H, Li CK, Cheung YT. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes in Asian survivors of childhood cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13:374-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang Y, Allen KJ, Suaini NHA, Peters RL, Ponsonby AL, Koplin JJ. Asian children living in Australia have a different profile of allergy and anaphylaxis than Australian-born children: A State-wide survey. Clin Exp Allergy. 2018;48:1317-1324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vang ZM, Sigouin J, Flenon A, Gagnon A. Are immigrants healthier than native-born Canadians? A systematic review of the healthy immigrant effect in Canada. Ethn Health. 2017;22:209-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Snijder MB, Galenkamp H, Prins M, Derks EM, Peters RJG, Zwinderman AH, Stronks K. Cohort profile: the Healthy Life in an Urban Setting (HELIUS) study in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Crowe R, Stanley R, Probst Y, McMahon A. Culture and healthy lifestyles: a qualitative exploration of the role of food and physical activity in three urban Australian Indigenous communities. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2017;41:411-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Williams GH. Converting-enzyme inhibitors in the treatment of hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1517-1525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Brown T, Gonzalez J, Monteleone C. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema: A review of the literature. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19:1377-1382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chen JY, Kang N, Juarez DT, Yermilov I, Braithwaite RS, Hodges KA, Legorreta A, Chung RS. Heart failure patients receiving ACEIs/ARBs were less likely to be hospitalized or to use emergency care in the following year. J Healthc Qual. 2011;33:29-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gullestad L, Aukrust P, Ueland T, Espevik T, Yee G, Vagelos R, Frøland SS, Fowler M. Effect of high- versus low-dose angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition on cytokine levels in chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:2061-2067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hagiwara S, Iwasaka H, Hidaka S, Hasegawa A, Koga H, Noguchi T. Antagonist of the type-1 ANG II receptor prevents against LPS-induced septic shock in rats. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1471-1478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wan L, Langenberg C, Bellomo R, May CN. Angiotensin II in experimental hyperdynamic sepsis. Crit Care. 2009;13:R190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Laesser M, Oi Y, Ewert S, Fändriks L, Aneman A. The angiotensin II receptor blocker candesartan improves survival and mesenteric perfusion in an acute porcine endotoxin model. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48:198-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ishigami T, Uchino K, Umemura S. ARBs or ACEIs, that is the question. Hypertens Res. 2006;29:837-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |