Published online Dec 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i34.8153

Peer-review started: July 12, 2023

First decision: August 24, 2023

Revised: October 18, 2023

Accepted: November 27, 2023

Article in press: November 27, 2023

Published online: December 6, 2023

Processing time: 147 Days and 5.3 Hours

Hepatic artery obstruction is a critical consideration in graft outcomes after living donor liver transplantation. We report a case of diffuse arterial vasospasm that developed immediately after anastomosis and was managed with an intra-arterial infusion of lipo-prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).

A 57-year-old male with hepatitis B virus-related liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma underwent ABO-incompatible living donor liver transplant. The grafted hepatic artery was first anastomosed to the recipient’s right hepatic artery stump. However, the arterial pulse immediately weakened. Although a new anastomosis was performed using the right gastroepiploic artery, the patient’s arterial pulse rate remained poor. We attempted angiographic intervention immediately after the operation; it showed diffuse arterial vasospasms like ‘beads on a string’. We attempted continuous infusion of lipo-PGE1 overnight via an intra-arterial catheter. The next day, arterial flow improved without any spasms or strictures. The patient had no additional arterial complications or related sequelae at the time of writing, 1-year post-liver transplantation.

Angiographic evaluation is helpful in cases of repetitive arterial obstruction, and intra-arterial infusion of lipo-PGE1 may be effective in treating diffuse arterial spasms.

Core Tip: Diffuse arterial spasms are difficult to correct surgically, and there are no clear standard management protocols. This short report shows that angiography is helpful for evaluating the hepatic artery after liver transplantation and that intra-arterial infusion of lipo-prostaglandin E1 might be an effective non-surgical treatment option for diffuse arterial spasms.

- Citation: Kim M, Lee HW, Yoon CJ, Lee B, Jo Y, Cho JY, Yoon YS, Lee JS, Han HS. Intra-arterial lipo-prostaglandin E1 infusion for arterial spasm in liver transplantation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(34): 8153-8157

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i34/8153.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i34.8153

Liver transplantation (LT) is a favorable treatment option for advanced liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and other life-threatening diseases. However, LT can be complicated depending on the recipient’s condition, immunological issues, and technical difficulties. Problems with LT include primary non-function, rejection, and biliary or vascular complications. Hepatic artery complications, such as thrombosis or stenosis, are among the most critical complications of LT[1,2]. They are more frequent in living donor LTs (LDLT) and can lead to anastomotic rupture, sepsis, diffuse intrahepatic biliary stricture, and graft failure[3-5]. Thus, arterial flow is usually evaluated using a duplex Doppler ultrasound scan before the operation is completed and again during the early postoperative period. Although hepatic artery complications are usually managed with thrombectomy and re-anastomosis, they can often be controlled with radiological intervention and medical management. Recently, we encountered a case of LT with diffuse arterial spasm that was not surgically corrected but was successfully managed with intra-arterial lipo-prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).

A 57-year-old male patient presented with hepatitis B virus-related liver disease and multiple HCCs.

Eventually, the patient underwent ABO-incompatible LDLT from his 29-year-old daughter despite having good liver function (Child-Pugh score, 5; Model for end-stage liver disease score, 8).

Although he underwent radiofrequency ablation for HCC, followed by four rounds of transarterial chemoembolization for two years, subsequent imaging studies still showed multiple dysplastic nodules or possible HCCs.

He presented with hepatitis B virus-related liver disease and multiple HCCs.

The patient’s blood type was B+, whereas the donor’s was AB+. The patient was treated with rituximab and plasmaphe

The right liver graft was retrieved laparoscopically, and the hepatic vein branch from segment 5 was reconstructed using a polytetrafluoroethylene artificial graft. No events occurred during the donor or bench surgeries. The graft weight was 654 g, and the graft-to-recipient weight ratio was 0.99. Anastomoses of the hepatic and portal veins were performed, and reperfusion was uneventful. The first and second warm ischemia times were 12 and 55 min, respectively, whereas the cold ischemia time was 58 min.

The graft hepatic artery was first anastomosed end-to-end to the recipient’s right hepatic artery stump using interrupted 8-0 nylon. The first pulse of the hepatic artery was good after the anastomosis. However, the arterial pulse was much weaker when rechecked after the bile duct anastomosis. We were unable to detect arterial flow in the graft using intraoperative Doppler imaging; thus, we removed the anastomosis and attempted re-anastomosis. No definitive arterial thrombosis was observed. After heparin injection into both arteries, re-anastomosis was performed in the same manner; however, the arterial pulse weakened. We decided to change the artery on the recipient’s side because of the poor quality of the recipient’s hepatic artery from the previous chemoembolization. We carefully dissected the right gastroepiploic artery (RGEA) from the lower body of the gastric greater curvature and created a new anastomosis in the same manner. However, the pulse rate of the hepatic artery was poor. We decided to perform an angiographic intervention immediately after the operation.

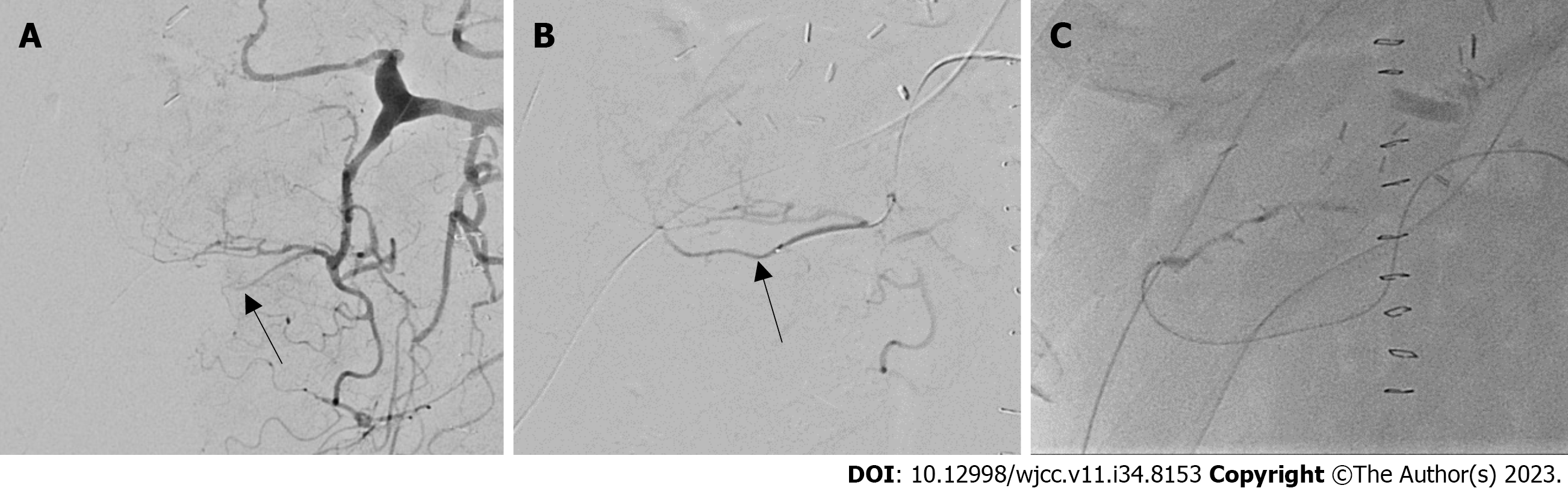

The RGEA was not well-delineated on the first angiography (Figure 1). Thrombolysis was induced by injecting heparin and a tissue plasminogen activator into the gastroduodenal artery just once. After thrombolysis, the RGEA and hepatic artery anastomosis sites were delineated.

Although there was no mechanical stricture at the anastomosis site, multiple irregular constrictions were found in the RGEA and graft hepatic artery, which looked like ‘beads on a string’ (Figure 2).

We attempted infusion of lipo-PGE1 via an arterial catheter for diffuse arterial spasm. We observed improvement in the spasm 10-20 min later. Thus, we decided to maintain the intra-arterial infusion of lipo-PGE1 overnight at 6 µg/h, in addition to an intravenous infusion of 20 µg/h, based on the routine protocol. Since there was no study of complications after such a liver transplant, there was no exact criterion for doses, so I started with a 1/3 dose of the Systemic Dose and then used a method of gradually increasing the spasm when F/U Angiography done on the following day revealed excellent arterial flow without spasms or strictures (Figure 3). Diffuse arterial spasms completely disappeared. We stopped the continuous infusion of intra-arterial PGE1 and removed the arterial catheter on the second postoperative day (POD).

Vascular flow was repeatedly evaluated using Doppler ultrasound every day until the third POD with dynamic computed tomography (CT) on the sixth POD. The arterial flow was good in all examinations, and no additional intervention was required. Intravenous lipo-PGE1 was administered until sixth postoperative POD. The patient was discharged on the thirteenth POD. A recent CT scan performed 10 mo post-LT also showed good arterial flow. Eventually, the patient had no additional arterial complications or related sequelae at the time of writing, 1-year post-LT.

Many studies have been published on hepatic artery complications after LT. The treatment of choice for these complications is revascularization by surgery or radiological intervention. However, because the anastomosis is very narrow and the arterial course may be tortuous in LDLT, an interventional approach may be difficult. If both surgery and intervention fail to correct these complications, the only way forward may be observation with or without medical treatment, and retransplantation may be needed in many situations[6].

Diffuse vasospasm of the hepatic artery is rare in LT, and its standard management remains unclear. Delayed cerebral ischemia due to cerebral vasospasm is known to be one of the most fatal complications after subarachnoid hemorrhage[7]. Treatment options for cerebral vasospasm include intravenous volume expansion, radiological interventions, such as balloon angioplasty, and intra-arterial injection of a vasodilator[7,8]. Diffuse arterial spasms are difficult to treat surgically. Although the spasm may be transient and leave no sequelae, it still needs to be thoroughly evaluated and managed because arterial flow disturbances in the early postoperative period can lead to diffuse intrahepatic cholangiopathy and graft failure.

As a vasodilator, PGE1 acts directly on the vascular smooth muscles and decreases the response to vasoconstriction[9]. PGE1 is commonly used in LT because of its effects on graft protection, including an increase in hepatic blood flow, enhanced recovery of mitochondrial respiration function after reperfusion, and stabilization of membrane microviscosity[10]. According to our LT protocol, we infuse lipo-PGE1 intravenously immediately after reperfusion, and continuous infusion of 20 μg/h is maintained through the sixth POD. In this case, we added lipo-PGE1 at 6 µg/h via an intra-arterial catheter. Diffuse spasms completely blocked arterial flow despite the administration of intravenous lipo-PGE1. Fortunately, intra-arterial infusion led to a quick improvement in the spasm, which resolved the next day.

The cause of the diffuse arterial spasm was not clarified in this case. Such an event is rare, and the present case represents our first experience. Hepatic artery vasospasms can resolve without treatment. Hepatic artery flow, however, is critical to the viability of the bile duct, and its insufficiency can cause fatal outcomes in LT.

Our experience shows that angiography is helpful for evaluating the hepatic artery after LT and that intra-arterial infusion of lipo-PGE1 may be effective in treating diffuse arterial spasms. Therefore, we suggest that early angiographic evaluation can be attempted in suspected post-LT arterial insufficiency cases, and intra-arterial PGE1 can be considered in patients with severe arterial spasms.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Transplantation

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gupta R, India; Li HL, China; Surani S, United States; Teragawa H, Japan S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Oh CK, Pelletier SJ, Sawyer RG, Dacus AR, McCullough CS, Pruett TL, Sanfey HA. Uni- and multi-variate analysis of risk factors for early and late hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;71:767-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Silva MA, Jambulingam PS, Gunson BK, Mayer D, Buckels JA, Mirza DF, Bramhall SR. Hepatic artery thrombosis following orthotopic liver transplantation: a 10-year experience from a single centre in the United Kingdom. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:146-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bekker J, Ploem S, de Jong KP. Early hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation: a systematic review of the incidence, outcome and risk factors. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:746-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Abbasoglu O, Levy MF, Vodapally MS, Goldstein RM, Husberg BS, Gonwa TA, Klintmalm GB. Hepatic artery stenosis after liver transplantation--incidence, presentation, treatment, and long term outcome. Transplantation. 1997;63:250-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Saad WE, Davies MG, Sahler L, Lee DE, Patel NC, Kitanosono T, Sasson T, Waldman DL. Hepatic artery stenosis in liver transplant recipients: primary treatment with percutaneous transluminal angioplasty. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:795-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Piardi T, Lhuaire M, Bruno O, Memeo R, Pessaux P, Kianmanesh R, Sommacale D. Vascular complications following liver transplantation: A literature review of advances in 2015. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:36-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 7. | Romner B, Reinstrup P. Triple H therapy after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. A review. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2001;77:237-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lennihan L, Mayer SA, Fink ME, Beckford A, Paik MC, Zhang H, Wu YC, Klebanoff LM, Raps EC, Solomon RA. Effect of hypervolemic therapy on cerebral blood flow after subarachnoid hemorrhage : a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 2000;31:383-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sinclair S, Levy G. Eicosanoids and the liver. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1990;22:205-213. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Ogawa M, Mori T, Mori Y, Ueda S, Yoshida H, Kato I, Iesato K, Wakashin Y, Wakashin M, Okuda K. Inhibitory effects of prostaglandin E1 on T-cell mediated cytotoxicity against isolated mouse liver cells. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:1024-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |