Published online Nov 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i32.7888

Peer-review started: August 22, 2023

First decision: September 19, 2023

Revised: September 21, 2023

Accepted: November 8, 2023

Article in press: November 8, 2023

Published online: November 16, 2023

Processing time: 83 Days and 19.8 Hours

Uterine rupture is a fatal medical complication with a high mortality rate. Most cases of uterine rupture occur in late pregnancy or during labor and are mainly related to uterine scarring due to previous surgical procedures. Adenomyosis is a possible risk factor for uterine rupture. However, spontaneous uterine rupture due to severe adenomyosis in a non-gravida-teenaged female has not been reported in the literature to date.

A 16-year-old girl was referred to our hospital for acute abdominal pain and hypovolemic shock with a blood pressure of 90/50 mmHg. Radiologic studies revealed a huge endometrial mass with multiple nodules in the lung, suggesting lung metastasis. The patient underwent an emergency total hysterectomy and wedge resection of the lung nodules. Histologically, the uterus showed diffuse adenomyosis with glandular and stromal dissociation. Lung nodules were endometrioma with massive hemorrhage. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated that the tumor cells were positive for PAX8, ER, and PR expression, leading to a final diagnosis of pulmonary endometriosis and uterine adenomyosis. Following surgery, the patient remains in good condition without recurrence.

This is the first case of spontaneous uterine rupture due to adenomyosis in a non-gravida adolescent.

Core Tip: Uterine adenomyosis is rare in adolescents but can lead to massive menorrhagia. Differential diagnoses, early detection, and therapeutic care must be provided to avoid hysterectomy in adolescents.

- Citation: Kim NI, Lee JS, Nam JH. Uterine rupture due to adenomyosis in an adolescent: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(32): 7888-7894

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i32/7888.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i32.7888

Adenomyosis is a commonly encountered estrogen-dependent disease in women across the lifespan, causing heavy menstrual bleeding, intense pelvic pain, and infertility[1]. Adenomyosis is associated with an increased risk of many obstetrical complications, such as uterine rupture, postpartum hemorrhage and fetal growth restriction[2].

Spontaneous uterine rupture due to adenomyosis in an adolescent and non-gravida female is extremely rare, with no cases reported in the literature. Here, we describe a unique case of uterine rupture due to adenomyosis with coexisting pulmonary endometriosis and review previously reported, similar cases[3-11].

A 16-year-old female visited the emergency department in hypovolemic shock.

The patient was obese (150 cm, 78 kg, body mass index 34.7 kg/m2) and complained of dysmenorrhea that suddenly occurred a month ago.

The patient was suffering from irregular menstrual period, heavy menstrual bleeding and was on ferrous sulfate medication for anemia (hemoglobin levels 9.2 g/dL). She had no history of taking other medications, including oral contraceptives or hormonal agents.

The patient was a virgin. She had no other significant personal or family history or previous surgical history. Menarche began at the age of 12.

Physical examination revealed a distended abdomen with diffuse abdominal tenderness. A palpable mass was not detected.

Laboratory findings showed decreased hemoglobin levels (6 g/dL). LDH (1476 U/L), CA-125 (1063 U/mL), and CA19-9 (1347 U/mL) levels were significantly increased. An hCG blood test was negative.

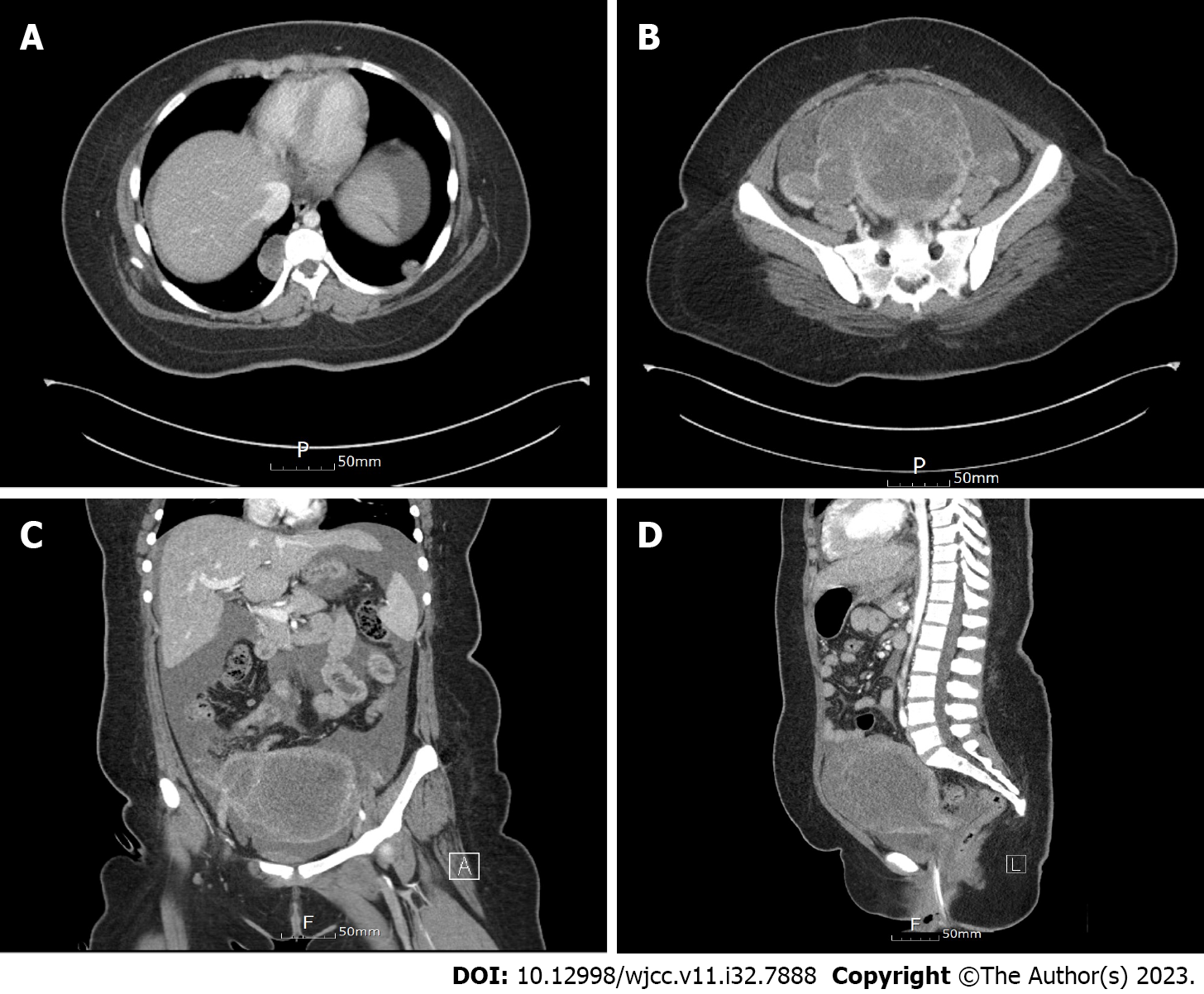

An enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the entire abdominal pelvic cavity revealed a 13 cm × 12.5 cm × 10 cm heterogeneously enhancing mass in the uterine corpus, suggesting a uterine malignancy (sarcomatous change of uterine myoma with lung metastasis), such as rhabdomyosarcoma or leiomyosarcoma (Figure 1). The chest CT also revealed enhancing lesions in the right lower lung (3.5 cm) and left lower lung (1.5 cm), suggesting metastatic lesions.

The preoperative differential diagnosis was uterine malignancy, such as rhabdomyosarcoma or leiomyosarcoma, with lung metastasis. However, there was no histologic evidence of malignancy in the resected surgical specimen. The final diagnosis was diffuse adenomyosis with extensive hemorrhage. Histopathology after a wedge resection confirmed pulmonary endometrioma of both lung nodules.

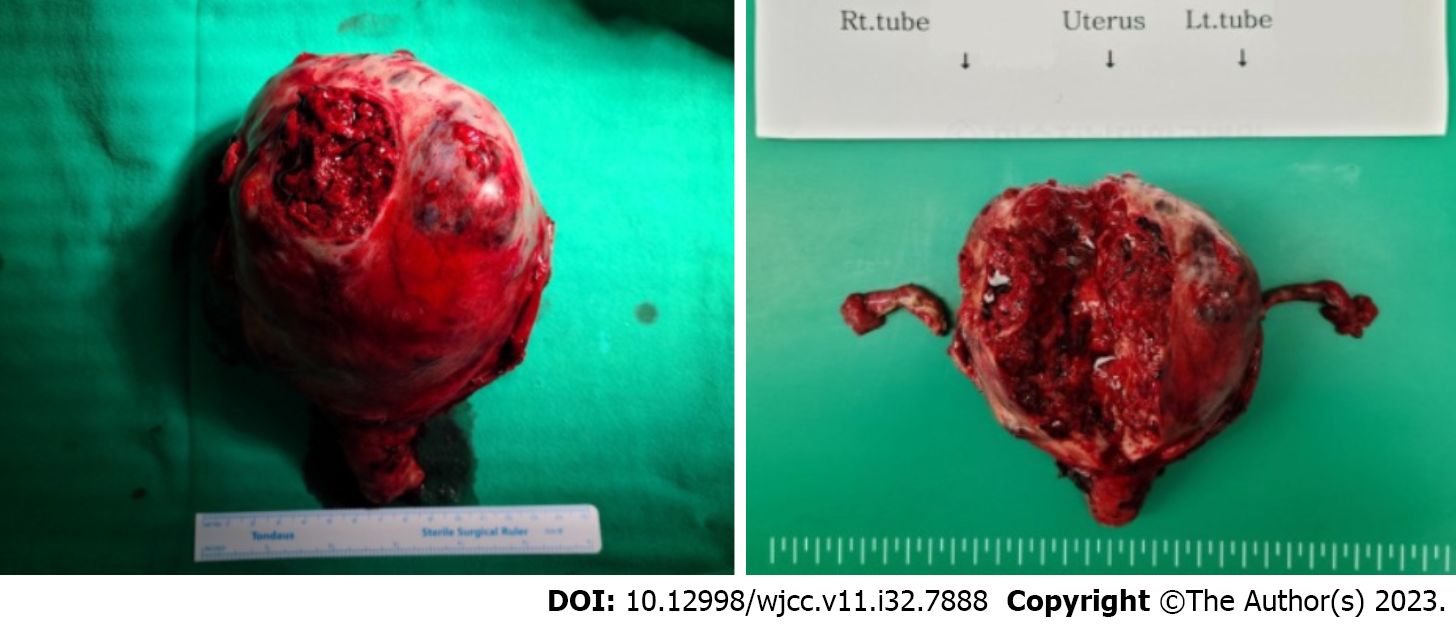

The patient underwent a total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy and wedge resection of the lung nodules. Intraoperative findings revealed a 4 L blood-filled abdominal cavity, a 15 cm sized huge necrotic tumor filling the uterus with blood, and multiple uterine perforations (Figure 2).

Macroscopic examination of the resected surgical specimen demonstrated an enlarged uterus with extensive hemorrhagic necrosis and hematoma. There were no definite mass-like lesions in the uterine corpus. Under low-power microscopy, the uterus showed extensive necrosis from the endometrium to the entire myometrium due to hemorrhage (Figure 3). Pathologic evaluation revealed diffuse adenomyosis with hemorrhagic necrosis and glandular and stromal dissociation.

While there was no evidence of malignancy in the uterine specimen, histology of the two lung nodules showed hemorrhagic cystic lesions lined by the cuboidal epithelium and surrounded by hemosiderin-laden macrophages. The cuboidal epithelium showed no cytologic atypia or mitotic activity. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD10, PAX8, ER, and PR and negative for TTF-1. Ectopic endometrial glands outside the uterine cavity confirmed a final diagnosis of pulmonary endometriosis.

All elevated blood tests normalized after surgery. Following surgery, radiologic studies revealed no specific abnormalities. The patient is currently taking Diengest (Visanne) and is doing well without any side effects or recurrence.

Adenomyosis is a gynecologic disorder, associated with a high risk of obstetric complications and adverse pregnancy outcomes[12]. Uterine rupture is an obstetric emergency with a high incidence of morbidity and mortality. It mostly occurs during the third trimester of pregnancy or delivery, with a prevalence rate of 0.05% in pregnant women[13]. A history of surgery, such as a cesarean section or myomectomy, is the most common risk factor for uterine rupture[14]. Advanced maternal age, multiparity, uterine malformation, excessive uterine pressure, and rare intrauterine manipulation are other important risk factors that may precipitate uterine rupture[15]. Spontaneous uterine rupture of an unscarred primigravid uterus is an extremely rare event[13,16]. Nikolaou et al[8] reported that nine of 12 cases of spontaneous uterine rupture were associated with adenomyosis.

Uterine adenomyosis involves the endometrial tissue growing into the uterine muscle wall of the uterus. This can cause painful menstrual periods, heavy bleeding, and pelvic pressure or discomfort. While adenomyosis mostly occurs in adult life, it can also involve adolescents in a mild to moderate form[17-23]. The exact cause of adenomyosis is unknown, but hormonal imbalances, uterine abnormalities, and certain medical conditions may increase the risk of this condition. Exacoustos et al[17] suggested using ultrasound as a diagnostic tool for adenomyosis could avoid the need for histologic diagnosis and facilitate appropriate management. Adenomyosis treatment may include medication or surgery in severe cases[1,22,24,25].

Obesity is associated with a higher risk of endometriosis and adenomyosis, although the exact relationship is unclear. The increasing incidence of adenomyosis and endometriosis in adolescents may be due to obesity[26]. Adenomyosis and endometriosis may increase the risk of obstetric complications[12]. Obesity can increase the risk of uterine rupture by increasing uterine pressure and may complicate the diagnosis of adenomyosis due to increased estrogen levels. Hormonal imbalances and inflammation may play a role in the development of both of these conditions in obese individuals[27].

However, hormones could cause different reactions to the adenomyotic stroma, especially in pregnant individuals. The adenomyotic stroma has two response patterns to pregnancy-related hormones. One is the superficial foci of adenomyosis, which are located within the endometrium’s basal layer with no to minimal decidualization. In the second pattern, deeper adenomyosis foci could exhibit prominent decidualization[3]. Higher expression of progesterone receptors in the stromal components of adenomyosis is likely related to stromal decidualization, supporting the theory that adenomyosis is a response to progesterone during pregnancy[8]. Furthermore, abundant decidual transformation of stromal cells in adenomyosis results in atrophy and necrosis of muscle cells[7]. Necrosis of the uterine muscles causes atony and muscle cell separation, leading to life-threatening rupture[28].

This could explain the spontaneous uterine rupture due to adenomyosis in pregnant women. About 15 cases of spontaneous uterine rupture due to adenomyosis have been reported to date (Table 1). Azziz[3] reviewed 11 cases of uterine rupture, seven of which were associated with adenomyosis. Uccella et al[29] reviewed the literature and found that 1 in 25 reported cases of prelabor spontaneous uterine rupture involved adenomyosis. Mueller et al[5] reported a primigravida woman who experienced spontaneous uterine rupture at 18 wk of gestation due to heavily decidualized adenomyosis. Nikolaou et al[8] reported a case of rupture of an unscarred uterus caused by multiple foci of adenomyosis with a marked decidual reaction in the adenomyotic stroma. Indraccolo et al[9] also reported a woman with uterine rupture caused by adenomyosis.

| Ref. | No. | Age | Gravida/Para | Endometriosis | Pregnancy | Hysterectomy |

| Azziz[3] (1986) | 1 | 41 | NA/P10 | NA | Yes | NA |

| 1 | NA | NA | NA | Yes | NA | |

| 1 | 25 | NA/P0 | NA | Yes | NA | |

| 1 | 38 | NA/P1 | NA | Yes | NA | |

| 1 | 33 | NA/P0 | NA | Yes | NA | |

| 1 | 25 | NA/P1 | NA | Yes | NA | |

| 1 | 26 | NA/P3 | NA | Yes | NA | |

| Bensaid et al[4] (1996) | 1 | 22 | G1/P1 | NA | Yes | No |

| Mueller et al[5] (1996) | 1 | 30 | G1/P0 | No | Yes | Total hysterectomy |

| Pafumi et al[6] (2001) | 1 | 30 | G3/P2 | No | Yes | Total hysterectomy |

| Villa et al[7] (2008) | 1 | 30 | G1/P1 | Rectovaginal endometriosis | Yes | Total hysterectomy |

| Nikolaou et al[8] (2013) | 1 | 33 | G1/P1 | Ovarian endometriosis | Yes | Subtotal hysterectomy |

| Indraccolo et al[9] (2015) | 1 | 37 | G2/P0 | No | Yes | No |

| Li et al[10] (2021) | 1 | 32 | G1/P0 | No | Yes | No |

| Vimercati et al[11] (2022) | 1 | 27 | G0/P0 | No | Yes | Total hysterectomy |

| Present case | 1 | 16 | G0/P0 | Pulmonary endometriosis | No | Total hysterectomy |

However, all previously reported cases were related to pregnancy, and the current case in a nulligravida juvenile patient is the first reported to date. The spontaneous uterine rupture in this nulligravida adolescent girl may be due to increased uterine pressure and changes in estrogen due to her obesity. We believe that transmural adenomyotic foci with significant hemorrhage and subsequent splaying of the myometrial smooth muscle fibers may have weakened the myometrium, ultimately rupturing the uterus.

Uterine rupture, a rare adenomyosis complication, can be fatal if not treated immediately. It can be difficult to diagnose adenomyosis, as the symptoms are similar to those of other conditions, such as endometriosis[30,31]. A preoperative diagnosis of spontaneous uterine rupture is also challenging, especially in a juvenile patient with nulligravida. Unrecognized adenomyosis is particularly problematic in younger patients[32]. The standard workup for all women who present with severe dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding should include an evaluation for adenomyosis, regardless of their age and health conditions. Regular monitoring is key to managing the risks associated with adenomyosis, especially in obese, nulliparous teenagers. Early detection may lower the risk of associated infertility and adverse obstetric outcomes, including uterine rupture[11].

The present case highlights the importance of considering a spontaneous uterine rupture diagnosis in women with a history of adenomyosis, regardless of their parity. Extensive adenomyosis may contribute to uterine wall weakness and increase the risk of uterine rupture, even in women who are not pregnant. If adenomyosis is detected early, fertility can be preserved with medical treatment and hysterectomy avoided.

Here we present an extraordinary case of spontaneous uterine rupture due to adenomyosis in a nulliparous adolescent. Uterine rupture should be considered for all female patients with adenomyosis, regardless of gestational status and history. It should be distinguished from other neoplastic conditions and early detection may lower the risk of adverse obstetric outcomes, including uterine rupture.

We are grateful to the patient for allowing us to use her medical records in our case report.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Krentel H, Peru; Mohey NM, Egypt S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Stratopoulou CA, Donnez J, Dolmans MM. Conservative Management of Uterine Adenomyosis: Medical vs. Surgical Approach. J Clin Med. 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Komatsu H, Taniguchi F, Harada T. Impact of adenomyosis on perinatal outcomes: a large cohort study (JSOG database). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23:579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Azziz R. Adenomyosis in pregnancy. A review. J Reprod Med. 1986;31:224-227. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Bensaid F, Kettani F, el Fehri S, Chraibi C, Alaoui MT. [Obstetrical complications of adenomyosis. Literature review and two case reports]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 1996;25:416-418. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Mueller MD, Saile G, Brühwiler H. [Spontaneous uterine rupture in the 18th week of pregnancy in a primigravida patient with adenomyosis]. Zentralbl Gynakol. 1996;118:42-44. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Pafumi C, Farina M, Pernicone G, Russo A, Bandiera S, Giardina P, Cianci A. Adenomyosis and uterus rupture during labor. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 2001;64:244-246. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Villa G, Mabrouk M, Guerrini M, Mignemi G, Colleoni GG, Venturoli S, Seracchioli R. Uterine rupture in a primigravida with adenomyosis recently subjected to laparoscopic resection of rectovaginal endometriosis: case report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:360-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nikolaou M, Kourea HP, Antonopoulos K, Geronatsiou K, Adonakis G, Decavalas G. Spontaneous uterine rupture in a primigravid woman in the early third trimester attributed to adenomyosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2013;39:727-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Indraccolo U, Iannicco A, Micucci G. A novel case of an adenomyosis-related uterine rupture in pregnancy. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2015;42:810-811. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Li X, Li C, Sun M, Li H, Cao Y, Wei Z. Spontaneous unscarred uterine rupture in a twin pregnancy complicated by adenomyosis: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e24048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vimercati A, Dellino M, Suma C, Damiani GR, Malvasi A, Cazzato G, Cascardi E, Resta L, Cicinelli E. Spontaneous Uterine Rupture and Adenomyosis, a Rare but Possible Correlation: Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Harada T, Taniguchi F, Harada T. Increased risk of obstetric complications in patients with adenomyosis: A narrative literature review. Reprod Med Biol. 2022;21:e12473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hofmeyr GJ, Say L, Gülmezoglu AM. WHO systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity: the prevalence of uterine rupture. BJOG. 2005;112:1221-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Walsh CA, Baxi LV. Rupture of the primigravid uterus: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62:327-34; quiz 353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vernekar M, Rajib R. Unscarred Uterine Rupture: A Retrospective Analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2016;66:51-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kishi Y, Suginami H, Kuramori R, Yabuta M, Suginami R, Taniguchi F. Four subtypes of adenomyosis assessed by magnetic resonance imaging and their specification. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:114.e1-114.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Exacoustos C, Lazzeri L, Martire FG, Russo C, Martone S, Centini G, Piccione E, Zupi E. Ultrasound Findings of Adenomyosis in Adolescents: Type and Grade of the Disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022;29:291-299.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Itam SP 2nd, Ayensu-Coker L, Sanchez J, Zurawin RK, Dietrich JE. Adenomyosis in the adolescent population: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22:e146-e147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dietrich JE. An update on adenomyosis in the adolescent. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;22:388-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Grover SR. Gynaecology problems in puberty. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;33:101286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Templeman C, Marshall SF, Ursin G, Horn-Ross PL, Clarke CA, Allen M, Deapen D, Ziogas A, Reynolds P, Cress R, Anton-Culver H, West D, Ross RK, Bernstein L. Adenomyosis and endometriosis in the California Teachers Study. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:415-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yu O, Schulze-Rath R, Grafton J, Hansen K, Scholes D, Reed SD. Adenomyosis incidence, prevalence and treatment: United States population-based study 2006-2015. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:94.e1-94.e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zannoni L, Del Forno S, Raimondo D, Arena A, Giaquinto I, Paradisi R, Casadio P, Meriggiola MC, Seracchioli R. Adenomyosis and endometriosis in adolescents and young women with pelvic pain: prevalence and risk factors. Minerva Pediatr. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Benagiano G, Brosens I, Habiba M. Adenomyosis: a life-cycle approach. Reprod Biomed Online. 2015;30:220-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kho KA, Chen JS, Halvorson LM. Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Adenomyosis. JAMA. 2021;326:177-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pantelis A, Machairiotis N, Lapatsanis DP. The Formidable yet Unresolved Interplay between Endometriosis and Obesity. ScientificWorldJournal. 2021;2021:6653677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hanson FK, Kishan R, MacLeay K, de Riese C. Investigating the Association Between Metabolic Syndrome and Adenomyosis [24B]. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:25S. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jovanović B, Petrović A, Petrović B. [Decidual transformation in adenomyosis during pregnancy as an indication for hysterectomy]. Med Pregl. 2009;62:185-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Uccella S, Cromi A, Bogani G, Zaffaroni E, Ghezzi F. Spontaneous prelabor uterine rupture in a primigravida: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:e6-e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Peng CR, Chen CP, Wang KG, Wang LK, Chen YY, Chen CY. Spontaneous rupture and massive hemoperitoneum from uterine leiomyomas and adenomyosis in a nongravid and unscarred uterus. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54:198-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sachedina A, Todd N. Dysmenorrhea, Endometriosis and Chronic Pelvic Pain in Adolescents. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2020;12:7-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Isaacson K, Loring M. Symptoms of Adenomyosis and Overlapping Diseases. Semin Reprod Med. 2020;38:144-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |