Published online Nov 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i32.7852

Peer-review started: July 8, 2023

First decision: August 24, 2023

Revised: September 6, 2023

Accepted: November 2, 2023

Article in press: November 2, 2023

Published online: November 16, 2023

Processing time: 130 Days and 19.5 Hours

Arterial bleeding typically involves the renal artery following partial nephrectomy; in this study, we present a case of bleeding originating from the testicular artery that has not been reported in previous studies.

A 52-year-old man suffered hemorrhage from a perinephric branch of the aberrant left testicular artery after an open nephron-sparing surgery for renal cell carcinoma. Clinical signs of bleeding were manifested by the patient, such as fresh blood drainage from the catheter, decreased hemoglobin levels, and significant vital sign changes. Since computed tomography did not show evidence of active bleeding, transcatheter angiography was conducted to identify the bleeding site. Fluoroscopic spot images confirmed bleeding derived from a perinephric branch of the testicular artery originating from the segmental artery of the left renal artery. Using n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate, successful transcatheter arterial embolization of the affected branch was performed. Immediately after the embolization procedure, the bleeding ceased, and the patient experienced complete recovery devoid of complications.

In patients with postoperative arterial hemorrhage after partial nephrectomy, the testicular artery can be a rare but notable source of bleeding. Accurate bleeding site localization via angiographic evaluation, followed by transcatheter arterial embolization, can be instrumental for safe, prompt, and effective hemostasis.

Core Tip: Arterial hemorrhage, one of the complications associated with post partial nephrectomy, primarily arises from an injury to the distal end of the renal artery located at the kidney’s resection margin. Herein, we present a rare case of hemorrhage following partial nephrectomy that originated from a perinephric branch of the testicular artery, arising from the segmental artery of the renal artery. Despite the absence of active bleeding on computed tomography scan, preemptive angiographic evaluation based on a strong clinical suspicion of hemorrhage was performed. This afforded precise bleeding site identification, followed by successful transcatheter arterial embolization. It is noteworthy that arterial hemorrhage after partial nephrectomy can originate not only from the renal artery but also from the perinephric branches of nonrenal arteries, including the testicular artery.

- Citation: Youm J, Choi MJ, Kim BM, Seo Y. Transcatheter embolization for hemorrhage from aberrant testicular artery after partial nephrectomy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(32): 7852-7857

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i32/7852.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i32.7852

Partial nephrectomy (PN), also known as nephron-sparing surgery, is preferred for surgical removal of renal tumor owing to its ability to preserve renal function[1-3]. However, the abundant renal tissue vascularity poses a potential risk of vascular complications associated with PN compared to radical nephrectomy[2,3]. Hemorrhage resulting from arterial injury following PN primarily occurs at the renal artery, located at the kidney’s resection margin[1,2,4,5]. In the literature, no documented cases have been reported regarding hemorrhage secondary to testicular artery injury following PN. While this may be attributed to the rarity of bleeding as a result of testicular artery injury, it is also plausible that the potential for hemorrhage originating from the testicular artery has been overlooked or underestimated. In arterial bleeding, spontaneous hemostasis is difficult to anticipate, and it can hinder postoperative recovery due to massive blood loss. Thus, prompt intervention, including surgical or endovascular treatment, is crucial. Transcatheter arterial embolization has been established as a safe and efficacious treatment strategy for managing post-PN bleeding[1,2,4,5]. However, to attain immediate and effective embolization, accurate bleeding site localization via angiography is necessary.

In this report, we present a case of active bleeding from a perinephric branch of the aberrant testicular artery following PN, and the diagnosis was established through angiographic evaluation, which was successfully managed using transcatheter embolization.

A 52-year-old male patient was referred to the Department of Interventional Radiology for angiographic evaluation and endovascular management to control postoperative bleeding after open PN.

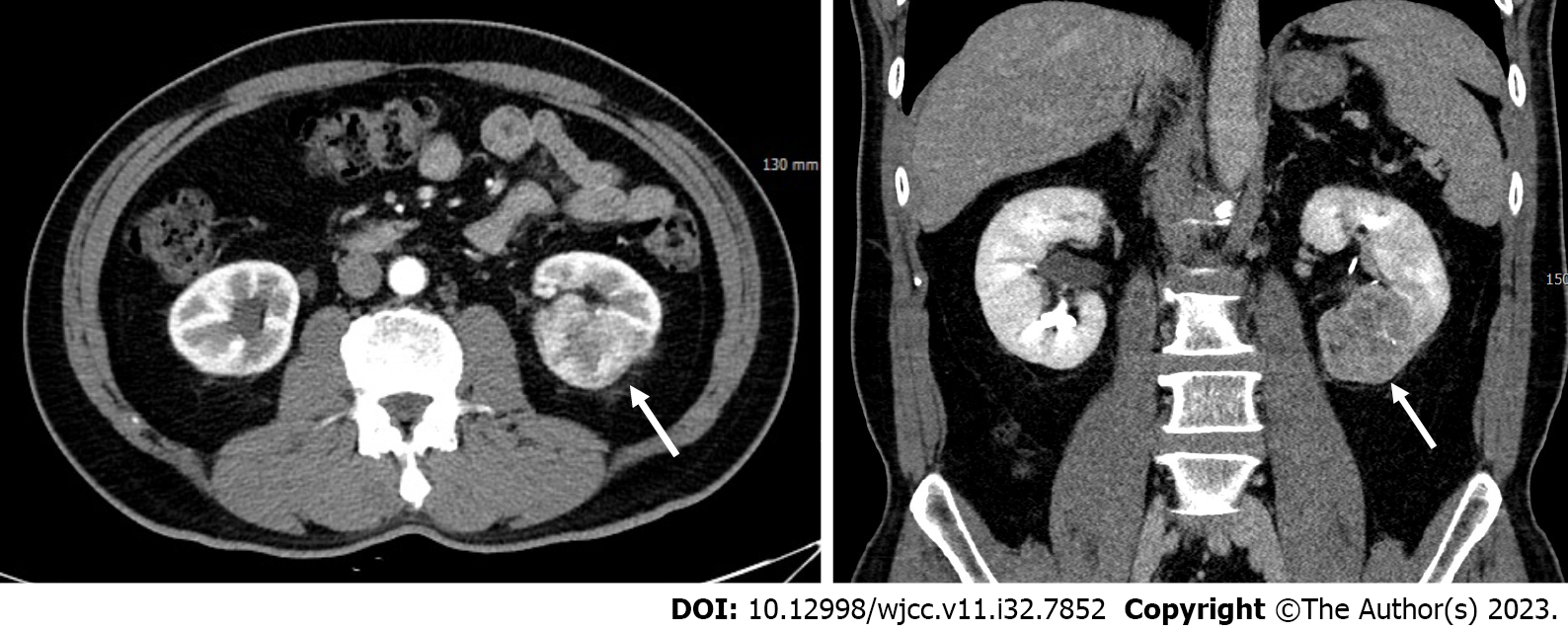

He underwent nephron-sparing surgery as an indication for left renal cell carcinoma (T1b) (Figure 1). Immediately after surgery, a continuous discharge of fresh blood was noted in the Jackson–Pratt drain, with a total drainage volume of 600 mL within 24 h postoperatively.

He had no underlying medical conditions or diseases that may indicate a coagulopathy.

His personal and family history was unremarkable.

His hemodynamic status was relatively stable as follows: Systolic blood pressure of 115 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure of 63 mmHg, and heart rate of 99 beats per minute. However, compared to his preoperative status, a decrease in blood pressure and a significant increase in heart rate were observed (systolic blood pressure of 145 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure of 86 mmHg, and heart rate of 66 beats per minute). He did not manifest with gross hematuria; however, he experienced abdominal and flank pain and tenderness, which are considered typical following renal surgery.

Laboratory examinations revealed a decline in the hemoglobin level from 13.4 g/dL to 11.4 g/dL, even after receiving transfusion of three units of packed red blood cells following surgery. Other laboratory findings were unremarkable.

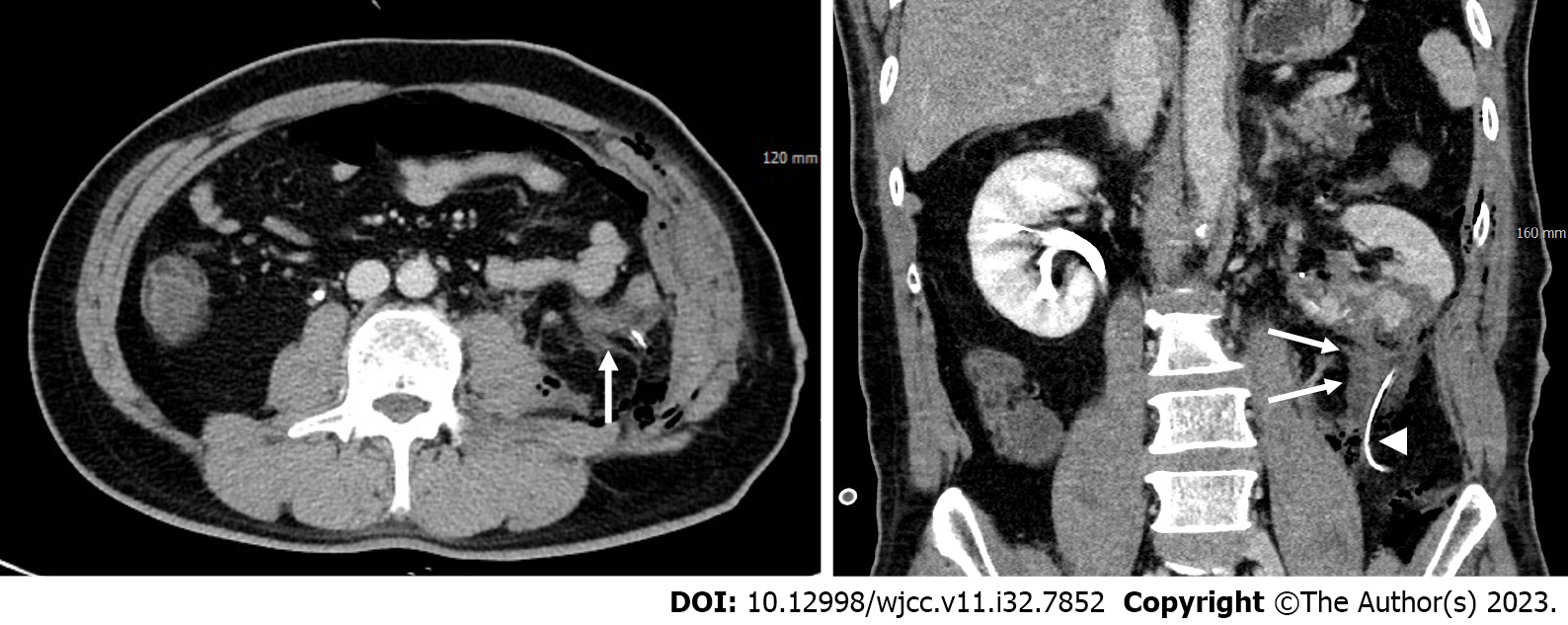

Minimal amount of fluid adjacent to the operative site of the left kidney was demonstrated in the abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT); however, no signs of contrast extravasation or pseudoaneurysm indicative of active bleeding were observed (Figure 2). The patient was referred to the interventional unit for angiographic evaluation and endovascular treatment due to clinical suspicion of active bleeding despite the absence of radiologic evidence.

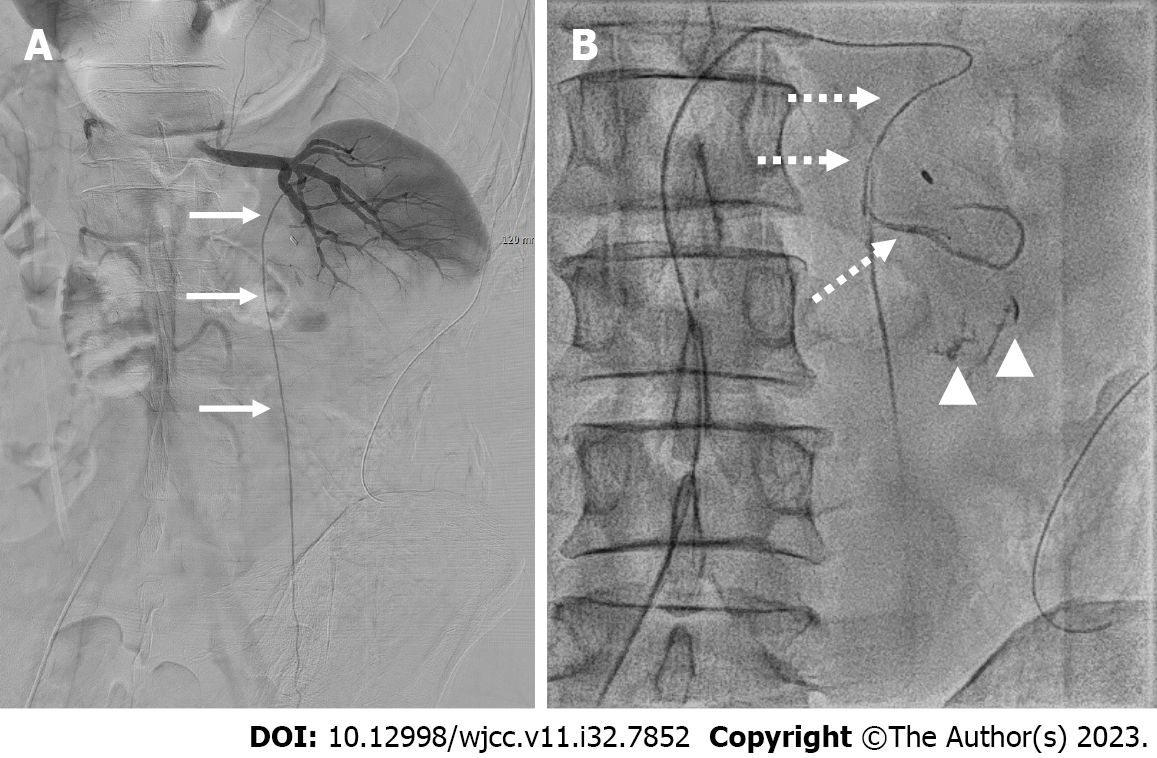

Selective digital subtraction angiography (DSA) was conducted for the left renal artery using a cobra catheter (Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, IN, United States). Angiographic opacification of left renal artery did not show any positive findings indicative of ongoing bleeding (Figure 3A). After catheterization of the left testicular artery (Figure 3A), which originated from the segmental artery of the left renal artery in the renal hilar shadow, contrast medium was injected using a microcatheter (Progreat; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) with a coaxial technique. Subsequently, extravasation of the contrast medium was noted on the fluoroscopic spot images (Figure 3B).

Hemorrhage from a perinephric branch of an aberrant testicular artery originating from the renal artery following open PN.

Transcatheter embolization was conducted for the culprit branch using a mixture of n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA) (Histoacryl, B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) diluted 1:3 in iodized oil (Lipiodol, Guerbet, Paris, France). The NBCA and iodized oil mixture was carefully injected into the bleeding site to achieve hemostasis while avoiding nontarget embolization of the testicular artery and renal artery. Subsequent fluoroscopy demonstrated a cast formation of the embolic material in the bleeding site (Figure 4).

Immediately after transcatheter embolization, bleeding from the Jackson–Pratt drain ceased, with no further decline in the hemoglobin levels. During the 6-mo clinical follow-up, the patient attained full recovery without any complications, such as renal or gonad dysfunction, indicating the absence of nontarget embolization.

For early stage renal cell carcinoma, PN has become the gold standard treatment, specifically T1a and some T1b cases[3]. While hemorrhage following PN is rare, it can potentially be fatal and is typically associated with renal bleeding. Unilateral open PN is performed via several steps, including a flank incision, kidney dissection inside the Gerota’s fascia, clamping of the renal arteries and veins, renal lesion resection, and renorrhaphy[3]. Renal tumor resection conveys a potential bleeding risk due to the abundant vascular tissue in the kidneys[2].

A retrospective study analyzing 1187 patients undergoing PN, approximately 3% of patients required embolization due to bleeding-related complications, all of which were related to renal bleeding[5]. Prior studies on endovascular treatment of post-PN bleeding have primarily highlighted on renal bleeding[1,2,4,5]. However, hemorrhage may also occur from the perinephric space or nearby retroperitoneum[3], particularly during the preresection stage of the PN. In our case, the perinephric fat presented with denser characteristics and a stronger attachment to the renal capsule than usual. This probably led to arterial injury supplying the perinephric fat tissue during kidney dissection from the perinephric fat inside the Gerota’s fascia.

The clinical features of post-PN bleeding include hematuria secondary to renal hemorrhage, flank pain, or renal dysfunction due to bleeding in the perirenal compartment, bleeding from suction drains, or decreased hemoglobin level[1]. In our case, since it was nonrenal bleeding, hematuria was not present. However, continuous drainage of fresh blood through the drainage tube, along with persistent hemoglobin decline despite transfusion, strongly raised clinical suspicion of active bleeding.

Radiologically, active bleeding is demonstrated through contrast medium extravasation, pseudoaneurysm, and arteriovenous fistula. In our case, CT and initial DSA findings did not provide evidence of active bleeding. This could be attributed to continuous drainage of blood through the drainage tube inserted during surgery. Finally, the bleeding site was identified on fluoroscopy by superselectively accessing each suspected vessel via a microcatheter and injecting a contrast agent.

A systemic approach to differential diagnosis is crucial in evaluating post-PN patients with suspected hemorrhage. Distinguishing between different potential sources of bleeding, such as renal artery bleeding, perirenal compartment bleeding, or other vascular abnormalities, is essential. Initial imaging examinations, including contrast-enhanced CT and selective DSA, may not always provide evidence of active bleeding. Therefore, to accurately guide diagnosis and intervention decisions, combining clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, and angiographic evaluation is crucial.

Compared to surgery, transcatheter embolization is less invasive but involves a crucial procedural step that needs to be employed. In contrast to the surgical approach, which allows direct visualization and control of the bleeding site, an endovascular approach requires an initial and essential step of identifying the parent artery of the bleeding vessel to achieve immediate and effective hemostasis.

To date, no cases of post-PN bleeding originating from the testicular artery branches have been reported, indicating that this possibility has been overlooked rather than deemed unlikely. The testicular artery leads to numerous branches that supply blood to the perinephric fat and ureter as it descends toward the pelvis and inguinal ring[6].

Our case report not only underscores the importance of accurate localization and timely intervention but also has significant implications for clinical practice. The possibility of testicular artery-related hemorrhage in post-PN patients should be considered by interventional radiologists and urologists when traditional sources of bleeding have been ruled out. Early recognition of such cases can lead to more targeted angiographic evaluations and timely transcatheter embolization, decreasing the risk of massive blood loss and expediting patient recovery.

The origin of the testicular artery from the renal artery is another noteworthy aspect of our case. The testicular artery usually originates directly from the lateral side of the abdominal aorta at the L2-L3 Level, just below the renal arteries’ ostium[6,7]. Nallikuzhy et al[6] reported the anomalous origin of the testicular artery by conducting a meta-analysis of variations in the testicular vasculature. In their study, a total of 2,396 testicular arteries were analyzed, and they found that 4.55% of cases (56 out of 1229) on the right side and 4.97% of cases (58 out of 1167) on the left side had the testicular artery originating from the renal artery or its associated arteries, such as an accessory renal artery. In this present case, the left testicular artery originated from the middle segmental artery of the left renal artery in the renal hilar portion.

NBCA is a permanent liquid embolic material that undergoes rapid polymerization upon contact with blood[8,9]. One particular advantage of NBCA is that it is not affected by the patient’s coagulation state[9]. In cases where it is challenging to advance the microcatheter adequately due to a tortuous vessel course or small-vessel diameters, embolization can be performed by adjusting the NBCA and iodized oil mixing ratio[9]. However, the use of this embolic material requires proficiency in its application by the operators. In our case, caution was exercised to prevent reflux into the peripheral portion of the renal artery and the testicular artery, ensuring that the embolic material was accurately and appropriately injected into the bleeding site.

This case elucidates that post-PN hemorrhage can be attributed to a perinephric branch originating from the testicular artery. Angiographic exploration plays a crucial role in the accurate identification of the bleeding site, allowing for a safe, prompt, and effective hemostasis through transcatheter arterial embolization.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shuang W, China S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Baumann C, Westphalen K, Fuchs H, Oesterwitz H, Hierholzer J. Interventional management of renal bleeding after partial nephrectomy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:828-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jeon CH, Seong NJ, Yoon CJ, Byun SS, Lee SE. Clinical results of renal artery embolization to control postoperative hemorrhage after partial nephrectomy. Acta Radiol Open. 2016;5:2058460116655833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Anastasiadis E, O'Brien T, Fernando A. Open partial nephrectomy in renal cell cancer - Essential or obsolete? Int J Surg. 2016;36:541-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gieraerts C, Vanhoutte E, Laenen A, Bonne L, De Wever L, Joniau S, Oyen R, Maleux G. Safety and efficacy of embolotherapy for severe hemorrhage after partial nephrectomy. Acta Radiol. 2020;61:1701-1707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shin J, Han K, Kwon JH, Kim GM, Kim D, Han SC, Kim HJ, Won JY, Kim MD, Lee DY. Clinical Results of Transarterial Embolization to Control Postoperative Vascular Complications after Partial Nephrectomy. J Urol. 2019;201:702-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nallikuzhy TJ, Rajasekhar SSSN, Malik S, Tamgire DW, Johnson P, Aravindhan K. Variations of the testicular artery and vein: A meta-analysis with proposed classification. Clin Anat. 2018;31:854-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mostafa T, Labib I, El-Khayat Y, El-Rahman El-Shahat A, Gadallah A. Human testicular arterial supply: gross anatomy, corrosion cast, and radiologic study. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:2226-2230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Madhusudhan KS, Venkatesh HA, Gamanagatti S, Garg P, Srivastava DN. Interventional Radiology in the Management of Visceral Artery Pseudoaneurysms: A Review of Techniques and Embolic Materials. Korean J Radiol. 2016;17:351-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yoo DH, Jae HJ, Kim HC, Chung JW, Park JH. Transcatheter arterial embolization of intramuscular active hemorrhage with N-butyl cyanoacrylate. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35:292-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |