Published online Nov 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i32.7806

Peer-review started: August 10, 2023

First decision: August 30, 2023

Revised: October 18, 2023

Accepted: November 9, 2023

Article in press: November 9, 2023

Published online: November 16, 2023

Processing time: 97 Days and 19.6 Hours

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) are common complications that affect the recovery and well-being of elderly patients undergoing gastrointestinal laparoscopic surgery.

To investigate the effect of butorphanol on PONV in this patient population.

A total of 110 elderly patients (≥ 65 years old) who underwent gastrointestinal laparoscopic surgery were randomly assigned to receive butorphanol (40 μg/kg) or sufentanil (0.3 μg/kg) during anesthesia induction in a 1:1 ratio. The measured outcomes included the incidence of PONV at 48 h after surgery, intraoperative dose of propofol and remifentanil, Bruggrmann Comfort Scale score in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU), number of compressions for postoperative patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCIA), and time to first flatulence after surgery.

The results revealed a noteworthy reduction in the occurrence of PONV at 24 h after surgery in the butorphanol group, when compared to the sufentanil group (T1: 23.64% vs 5.45%, T2: 43.64% vs 20.00%, P < 0.05). However, no significant variations were observed between the two groups, in terms of the clinical characteristics, such as the PONV or motion sickness history, intraoperative and postoperative 48-h total infusion volume and hemodynamic parameters, intraoperative dose of propofol and remifentanil, number of postoperative PCIA compressions, time until the first occurrence of postoperative flatulence, and incidence of PONV at 48 h post-surgery (all, P > 0.05). Furthermore, patients in the butorphanol group were more comfortable, when compared to patients in the sufentanil group in the PACU.

The present study revealed that butorphanol can be an efficacious substitute for sufentanil during anesthesia induction to diminish PONV within 24 h following gastrointestinal laparoscopic surgery in the elderly, simultaneously improving patient comfort in the PACU.

Core Tip: In this study, butorphanol was used for anesthesia induction, and it was found that the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting was significantly lower at 24 h after surgery in the butorphanol group, when compared to the sufentanil group. In addition, the Bruggrmann Comfort Scale scores in the postanesthesia care unit were significantly better in the butorphanol group, when compared to the sufentanil group.

- Citation: Xie F, Sun DF, Yang L, Sun ZL. Effect of anesthesia induction with butorphanol on postoperative nausea and vomiting: A randomized controlled trial. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(32): 7806-7813

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i32/7806.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i32.7806

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is the second most common postoperative adverse reaction after pain, which has an estimated incidence of 30% in the general surgical population, and an incidence that can reach as high as 80% in high-risk patients[1]. Aspiration pneumonia caused by PONV is a severe risk, particularly in elderly patients with poor pharyngeal reflex recovery after general anesthesia. In addition, PONV may cause electrolyte imbalance, poor incision healing, insufficient blood volume, and delayed discharge from the hospital.

The concept of enhanced rehabilitation after surgery emphasizes the role of minimizing adverse reactions after surgery, in order to improve the quality and pace of recovery[2]. The high-risk types of surgery with PONV include laparoscopic, bariatric, and gynecological surgery. The mechanism of PONV induced by the laparoscopic surgery remains unclear. Recent clinical studies have suggested that this may be correlated to the decrease in pain threshold of patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery, the stimulation of residual postoperative carbon dioxide in the abdominal cavity, and the pulling state of the peritoneum, which can result in increased demand for postoperative analgesia, such as opioids, leading to an increased likelihood of PONV[3]. For patients undergoing gastrointestinal laparoscopic surgery, nausea and vomiting are more likely to occur after surgery. Therefore, the balance between analgesia and PONV remains as a major challenge for anesthesiologists.

Traditional opioids produce an analgesic effect by exciting the μ (μ1 and μ2) receptors. However, the excitation of μ2 receptors can enhance the sensitivity to vestibule stimulation, affect the chemoreceptor triggering area, and delay gastric emptying, thereby triggering PONV[4]. In contrast, butorphanol, which is a synthetic opioid receptor agonist-antagonist with 5-8 times the analgesic potency of morphine, exhibits low activity to δ receptors, while stimulating the κ and μ1 receptors, and antagonizing μ2 receptors[5]. Through its antagonistic effect on μ2 receptors, butorphanol significantly reduces the incidence of PONV caused by traditional opioids. Furthermore, clinical studies have revealed that butorphanol has a good analgesic effect on patients with chronic visceral pain through the activation of κ receptors[6,7]. At present, few studies have compared butorphanol and sufentanil in the incidence of PONV during general anesthesia. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the effect of butorphanol on PONV in elderly patients who underwent gastrointestinal laparoscopic surgery.

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University (PJ-KS-KY-2020-161 [X]), and registered in the China Clinical Trial Center (ChiCTR2100045860). Patients ≥ 65 years old, who underwent gastrointestinal laparoscopic surgery from February 2020 to February 2021, were enrolled for the present study. Using the computer statistics software, these patients were randomly allocated into two groups in a 1:1 ratio: Sufentanil and butorphanol groups.

Based on preliminary experiments and previous studies[8], the sample size was calculated according to the incidence of PONV. The preliminary experiment results indicated that the incidence of PONV was approximately 35% in the sufentanil group, and 13% in the butorphanol group. In order to ensure adequate statistical power with 85% power at 5% level of significance, at least 49 patients were required for each group. Accounting for the potential 10% dropout rate, a total of 110 patients were included for the present study.

Inclusion criteria: Patients ≥ 65 years old, who underwent gastrointestinal laparoscopic surgery, and provided a written informed consent. Exclusion criteria: Hypersensitivity to butorphanol and sufentanil, serious respiratory complications, severe obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome or obesity [body mass index (BMI) ≥ 28 kg/m2], opioid dependence, significant abnormalities in liver or kidney function, and severe visual or auditory impairment.

The following basic clinical information were recorded at one day prior to surgery: Age, gender, height, weight, BMI, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, smoking status, and history of PONV and motion sickness. These patients were required to fast for six hours, and have water deprivation for two hours before the surgery, with no preoperative drugs administered. Upon entering the operation room, the electrocardiogram, heart rate, oxygen saturation (SpO2), non-invasive blood pressure, bispectral index, and oral and sublingual temperature were monitored. In addition, invasive arterial blood pressure was monitored via radial artery catheterization and internal jugular vein catheterization, in order to detect any hemodynamic changes, and facilitate the administration of fluids and medications, when necessary.

Anesthesia induction was administered to patients in the sufentanil group at a dose of 0.3 μg/kg of sufentanil, while patients in the butorphanol group were given 40 μg/kg of butorphanol, based on the analgesic titer ratio. During the anesthesia induction, the intravenous administration of 1-2 mg/kg of propofol and 0.3 mg/kg of benzensulfonate atracurium was performed, while remifentanil was pumped at a rate of 5-10 μg/kg/h. Then, tracheal intubation was performed under visual laryngoscopy after the muscle relaxant took effect. The anesthesia maintenance during the operation consisted of the intravenous infusion of 4-6 mg/kg/h of propofol, 5-10 μg/kg/h of remifentanil, and 0.10-0.15 mg/kg/h of benzenesulfonate atracurium. When the surgery was completed, the infusion of benzenesulfonate atracurium, propofol and remifentanil were stopped, while 0.1 mg/kg of butorphanol was given for patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCIA). Then, these patients were transferred to the postanesthesia care unit (PACU), and vital signs monitoring was continued for 48 h. The study assistants were responsible for the preparation and administration of the studied medications. The other assistants were responsible for the monitoring and recording of the results during data collection. All assistants were blinded to the study.

The primary outcome of the study was the incidence of PONV, which was evaluated using the PONV grading scale in the PACU (T1), and at 24 h (T2) and 48 h (T3) after surgery (Table 1). The other observed parameters were, as follows: Intra

| PONV grade | Patient response |

| 0 | Without PONV |

| I | Nausea without vomiting |

| II | Nausea with vomiting (< 3 times/d) |

| III | Vomiting ≥ 3 times/d |

For normally distributed measurement data, mean ± SD was used for the statistical description, and independent sample t-test was performed to determine the statistical difference. For non-normally distributed measurement data, median (M) and interquartile range were used for the statistical description, and the Mann-Whitney U-test was performed to determine the statistical difference. χ2 test was used to analyze the difference between groups for the enumeration data. Frequency (rate) was used to describe the ordinal data, and this was analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. SPSS 26.0 was used for the statistical analysis. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

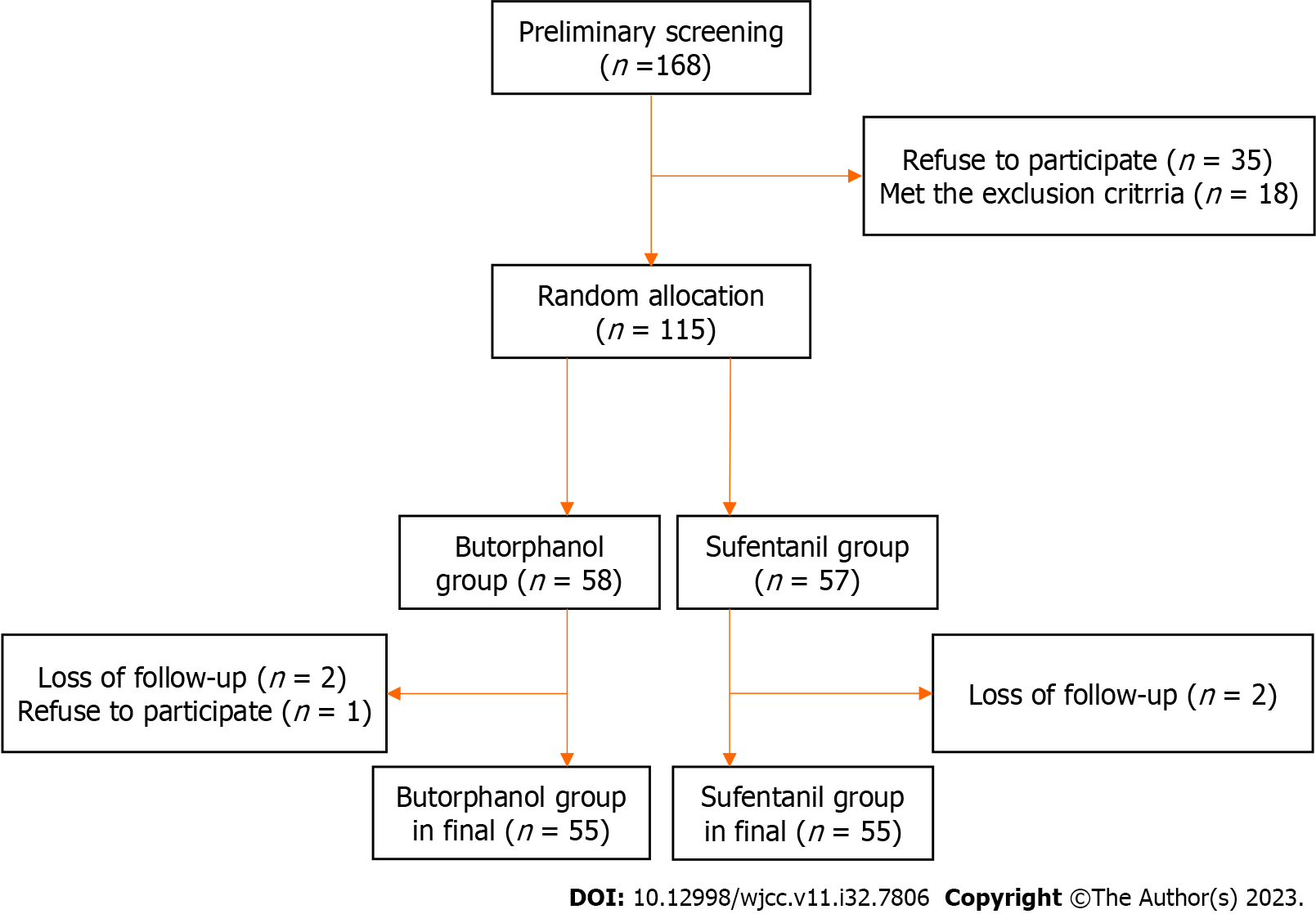

A total of 168 elderly patients, who underwent gastrointestinal laparoscopic surgery from February 2020 to February 2021, were screened in the present study. Among these patients, 35 patients did not agree to participate, and 18 patients were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. During the trial, five patients were excluded due to the following reasons: Rejection and loss to follow-up. Finally, a total of 110 patients (66 male and 44 female patients) were included for the present study (Figure 1).

No significant differences were observed between the two groups, in terms of age, BMI, gender, ASA grade, smoking history, PONV or motion sickness history, intraoperative and postoperative 48-h total infusion volume (Table 2), and hemodynamic parameters (Table 3) (P > 0.05).

| Sufentanil group (n = 55) | Butorphanol group (n = 55) | P value | |

| Age | 71.0 ± 5.7 | 69.6 ± 5.7 | 0.199 |

| Gender (male/female) | 32/23 | 34/21 | 0.698 |

| ASA (I/II/III) | 0/33/22 | 0/30/25 | 0.847 |

| Weight (kg) | 63.6 ± 10.3 | 68.6 ± 11.3 | 0.058 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.1 ± 1.8 | 20.81 ± 1.7 | 0.403 |

| Smoking (yes/no) | 25/30 | 26/29 | 0.703 |

| PONV or motion sickness history (yes/no) | 14/41 | 20/35 | 0.218 |

| Operation time (h) | 3.41 ± 1.30 | 3.25 ± 1.07 | 0.484 |

| Intraoperative infusion volume (mL) | 1290.9 ± 404.7 | 1243.6 ± 316.8 | 0.497 |

| Postoperative 24-h infusion volume (mL) | 2380.9 ± 137.6 | 2342.7 ± 133.8 | 0.143 |

| Postoperative 48-h infusion volume (mL) | 2152.7 ± 128.9 | 2125.5 ± 117.4 | 0.249 |

| HR (BPM) | SBP (mmHg) | DBP (mmHg) | |||||||

| Sufentanil | Butorphanol | P value | Sufentanil | Butorphanol | P value | Sufentanil | Butorphanol | P value | |

| Pre-operation | 69.2 ± 9.0 | 67.9 ± 7.1 | 0.400 | 145.2 ± 15.2 | 146.1 ± 12.0 | 0.748 | 67.8 ± 6.2 | 67.51 ± 5.1 | 0.828 |

| One minute before induction | 70.2 ± 9.5 | 68.8 ± 6.5 | 0.348 | 149.5 ± 17.9 | 149.3 ± 12.4 | 0.966 | 71.2 ± 8.8 | 68.4 ± 5.4 | 0.056 |

| One minute after tracheal intubation | 69.8 ± 9.2 | 68.8 ± 6.1 | 0.480 | 144.3 ± 18.4 | 147.8 ± 10.5 | 0.233 | 69.5 ± 8.7 | 67.6 ± 4.3 | 0.156 |

| Intraoperative maintenance | 67.3 ± 8.1 | 68.5 ± 6.3 | 0.388 | 145.2 ± 13.9 | 149.1 ± 9.8 | 0.098 | 68.3 ± 7.6 | 68.1 ± 4.5 | 0.867 |

As shown in Table 4, there was a significant difference in the occurrence of PONV at T1 (P = 0.005) and T2 (P = 0.001), while there was no statistical difference at T3 (P = 0.169), between the sufentanil and butorphanol groups (Table 4).

There was no significant difference in the total dose of intraoperative propofol (P = 0.893) and remifentanil (P = 0.438) between the sufentanil and butorphanol groups (Table 5).

| Sufentanil group (n = 55) | Butorphanol group (n = 55) | Z | P value | |

| Propofol (mg) | 1027.2 ± 461.6 | 1016.4 ± 379.4 | - | 0.893 |

| Remifentanil (mg) | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | - | 0.438 |

| Agitation score (0/1/2/3) | 42/8/5/0 | 47/6/2/0 | -0.774 | 0.439 |

| BCS score (0/1/2/3/4) | 6/5/30/14/0 | 1/4/24/25/1 | -2.195 | 0.028a |

| Effective compressions of PCIA | 1.00 (2.00-1.00) | 1.00 (2.00-1.00) | - | 0.881 |

The BCS scores were significantly better in the butorphanol group, when compared to the sufentanil group (P = 0.028), although there was no significant difference in agitation scores in the PACU between the two groups (P = 0.439) (Table 5).

There were no statistically significant differences observed between the two groups, in terms of the number of PCIA effective compressions at postoperative 48 h (P = 0.881), and at the time to first postoperative flatulence (P = 0.822) (Table 5).

The present study compared the effects of sufentanil and butorphanol on the incidence of PONV in elderly patients who underwent gastrointestinal laparoscopic surgery. The results revealed that the incidence of PONV was lower in the PACU, and at 24 h after surgery in the butorphanol group, when compared to the sufentanil group, although there was no statistical difference observed at 48 h after surgery between the two groups.

The complex mechanism of PONV involves the following risk factors: Female gender, smoking, history of PONV or motion sickness, and opioids[12,13]. Several studies have revealed that traditional opioids that are commonly used for pain management, such as μ agonists, have been associated with nausea and vomiting, while providing analgesic efficacy[14,15]. Traditional opioids produce an analgesic effect by exciting the μ (μ1 and μ2) receptors. However, the excitation of μ2 receptors can enhance the sensitivity to vestibule stimulation, affect the chemoreceptor triggering area, and delay gastric emptying, thereby triggering PONV[4].

Butorphanol, which is a synthetic opioid receptor agonist-antagonist with 5-8 times the analgesic potency of morphine, exhibits low activity to δ receptors, while stimulating the κ and μ1 receptors, and antagonizing μ2 receptors[5]. Sufentanil has a long clearance half-life in elderly patients, and its effect on opioid receptors can persist for several hours after surgery, increasing the incidence and duration of PONV. Since sufentanil undergoes metabolism and clearance over time, its effect on opioid receptors decreases, which may explain the different effects of sufentanil and butorphanol on PONV at different time points.

Recent studies have revealed that butorphanol can effectively inhibit the hemodynamic fluctuations caused by tracheal intubation during anesthesia induction, which is consistent with the results of the hemodynamic parameter analysis in a previous study[16]. In the present study, there was no significant difference in hemodynamic fluctuations before and after endotracheal intubation between the sufentanil and butorphanol groups, and both drugs effectively inhibited the circulation fluctuations caused by the endotracheal intubation. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in intraoperative remifentanil dose, PACU agitation score, or the number of effective compressions for postoperative PCIA between the sufentanil and butorphanol groups. Thus, it was considered that the induction of anesthesia with butorphanol can produce similar and relatively complete analgesic effects as sufentanil. More importantly, butorphanol can activate the κ receptors, and exert sedative effects. Although there was no statistical difference in intraoperative propofol dose between the two groups in the present study, the BCS scores were higher in the butorphanol group, indicating that the postoperative comfort level of patients induced by butorphanol was higher.

Previous studies have reported that intravenous butrophanol can promote the recovery of postoperative gastro

The limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. Merely the occurrence of nausea and vomiting within 48 h after surgery were observed, and the PDNV was not followed up. Furthermore, the present study merely included elderly patients ≥ 65 years old, who underwent gastrointestinal laparoscopic surgery. Thus, patients in other age groups, especially young women, needs to be investigated. Moreover, the specific operation methods of gastrointestinal surgery were not statistically analyzed in the present study. In addition, other high-risk surgeries, such as pelvic surgery, thyroid surgery, strabismus repair, and middle ear surgery, were not included in the present study[18,19]. Therefore, the conclusions need to be supported by further evidence and more information.

In summary, the administration of butorphanol has shown potential in significantly reducing the occurrence of PONV within 24 h after gastrointestinal surgery in elderly patients, and improving the comfort of patients in the PACU. Therefore, the present study contributes valuable evidence that support strategies targeted at mitigating PONV during the perioperative period.

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) are common complications after surgery, seriously affects the prognosis of elderly patients for laparoscopic gastrointestinal surgery.

This prospective, double-blind randomized controlled trial aimed to investigate the effect of butorphanol on PONV in this patient population.

Elderly patients (≥ 65 years old) who underwent gastrointestinal laparoscopic surgery.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive butorphanol (40 μg/kg) or sufentanil (0.3 μg/kg) during anesthesia induction in a 1:1 ratio. The measured outcomes included the incidence of PONV at 48 h after surgery, intraoperative dose of propofol and remifentanil, Bruggrmann Comfort Scale (BCS) score in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU), number of compressions for postoperative patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCIA), and time to first flatulence after surgery.

The results revealed a noteworthy reduction in the occurrence of PONV at 24 h after surgery in the butorphanol group, when compared to the sufentanil group. However, no significant variations were observed between the two groups, in terms of the clinical characteristics, such as the PONV or motion sickness history, intraoperative and postoperative 48-h total infusion volume and hemodynamic parameters, intraoperative dose of propofol and remifentanil, number of postoperative PCIA compressions, time until the first occurrence of postoperative flatulence, and incidence of PONV at 48 h post-surgery. Furthermore, patients in the butorphanol group were more comfortable, when compared to patients in the sufentanil group in the PACU.

The administration of butorphanol has shown potential in significantly reducing the occurrence of PONV within 24 h after gastrointestinal surgery in elderly patients, and improving the comfort of patients in the PACU.

Anesthesia induction with butorphanol may reduce the incidence of PONV, especially for some patients with a high risk of PONV (young women, no-smoking, PONV or motion sickness history, high-risk surgeries, such as pelvic surgery, thyroid surgery, strabismus repair, and middle ear surgery).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Higa K, Japan S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Gan TJ, Belani KG, Bergese S, Chung F, Diemunsch P, Habib AS, Jin Z, Kovac AL, Meyer TA, Urman RD, Apfel CC, Ayad S, Beagley L, Candiotti K, Englesakis M, Hedrick TL, Kranke P, Lee S, Lipman D, Minkowitz HS, Morton J, Philip BK. Fourth Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:411-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 593] [Article Influence: 118.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Seyfried S, Herrle F, Schröter M, Hardt J, Betzler A, Rahbari NN, Reißfelder C. [Initial experiences with the implementation of the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) protocol]. Chirurg. 2021;92:428-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stoops S, Kovac A. New insights into the pathophysiology and risk factors for PONV. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2020;34:667-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sande TA, Laird BJA, Fallon MT. The Management of Opioid-Induced Nausea and Vomiting in Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review. J Palliat Med. 2019;22:90-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Laffey DA, Kay NH. Premedication with butorphanol. A comparison with morphine. Br J Anaesth. 1984;56:363-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Deflers H, Gandar F, Bolen G, Detilleux J, Sandersen C, Marlier D. Effects of a Single Opioid Dose on Gastrointestinal Motility in Rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus): Comparisons among Morphine, Butorphanol, and Tramadol. Vet Sci. 2022;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tang W, Luo L, Hu B, Zheng M. Butorphanol alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and apoptosis of cardiomyocytes via activation of the κ-opioid receptor. Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:1248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kranke P, Meybohm P, Diemunsch P, Eberhart LHJ. Risk-adapted strategy or universal multimodal approach for PONV prophylaxis? Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2020;34:721-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhao Y, Qin F, Liu Y, Dai Y, Cen X. The Safety of Propofol Versus Sevoflurane for General Anesthesia in Children: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Surg. 2022;9:924647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zong S, Du J, Chen Y, Tao H. Application effect of dexmedetomidine combined with flurbiprofen axetil and flurbiprofen axetil monotherapy in radical operation of lung cancer and evaluation of the immune function. J BUON. 2021;26:1432-1439. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Ren C, Xu H, Xu G, Liu L, Liu G, Zhang Z, Cao JL. Effect of intraoperative infusion of dexmedetomidine on postoperative recovery in patients undergoing endovascular interventional therapies: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Brain Behav. 2019;9:e01317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huynh P, Villaluz J, Bhandal H, Alem N, Dayal R. Long-Term Opioid Therapy: The Burden of Adverse Effects. Pain Med. 2021;22:2128-2130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Azzam AAH, McDonald J, Lambert DG. Hot topics in opioid pharmacology: mixed and biased opioids. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:e136-e145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mercadante S. Opioid Analgesics Adverse Effects: The Other Side of the Coin. Curr Pharm Des. 2019;25:3197-3202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mercadante S, Arcuri E, Santoni A. Opioid-Induced Tolerance and Hyperalgesia. CNS Drugs. 2019;33:943-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kaur J, Srilata M, Padmaja D, Gopinath R, Bajwa SJ, Kenneth DJ, Kumar PS, Nitish C, Reddy WS. Dose sparing of induction dose of propofol by fentanyl and butorphanol: A comparison based on entropy analysis. Saudi J Anaesth. 2013;7:128-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lyu SG, Lu XH, Yang TJ, Sun YL, Li XT, Miao CH. [Effects of patient-controlled intravenous analgesia with butorphanol versus sufentanil on early postoperative rehabilitation following radical laparoscopic nephrectomy]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2020;100:2947-2951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Aydin A, Kaçmaz M, Boyaci A. Comparison of ondansetron, tropisetron, and palonosetron for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after middle ear surgery. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2019;91:17-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Künzli BM, Walensi M, Wilimsky J, Bucher C, Bührer T, Kull C, Zuse A, Maurer CA. Impact of drains on nausea and vomiting after thyroid and parathyroid surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2019;404:693-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |