Published online Oct 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i29.7193

Peer-review started: July 6, 2023

First decision: July 18, 2023

Revised: July 28, 2023

Accepted: September 18, 2023

Article in press: September 18, 2023

Published online: October 16, 2023

Processing time: 99 Days and 13.2 Hours

Laparoscopic choledocholithotomy for a large impacted common bile duct (CBD) stone is a challenging procedure because of the technical difficulty and the possibility of postoperative complications, even in this era of minimally invasive surgery. Herein, we present a case of large impacted CBD stones.

A 71-year-old man showed a distal CBD stone (45 mm × 20 mm) and a middle CBD stone (20 mm × 15 mm) on computed tomography. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography failed due to the large size of the impacted stone and the presence of a large duodenal diverticulum. Laparoscopic choledocholithotomy was decided, and we used a near-infrared indocyanine green fluorescence scope to detect and expose the supraduodenal CBD more accurately. Then, the location, size, and shape of the stones were detected using a laparoscopic intraoperative ultrasound. The CBD was opened with a 2-cm-sized vertical incision. After irrigating several times, two CBD stones were removed with the Endo BabcockTM. T-tube insertion was done for postoperative cholangiography and delayed the removal of remnant sludge. The patient had no postoperative complications.

Laparoscopic choledocholithotomy by transcholedochal approach and transductal T-tube insertion is a safe and feasible option for large-sized impacted CBD stones.

Core Tip: Laparoscopic choledocholithotomy for a large impacted common bile duct (CBD) stone is a challenging procedure, even in this era of minimally invasive surgery. A 71-year-old man showed a distal CBD stone (45 mm) and a middle CBD stone (20 mm). Laparoscopic choledocholithotomy was performed with a near-infrared indocyanine green fluorescence scope and laparoscopic intraoperative ultrasound. Two CBD stones were successfully removed with the Endo BabcockTM, and T-tube insertion was done. This case shows that laparoscopic choledocholithotomy by the transcholedochal approach and transductal T-tube insertion is a safe and feasible option for large-sized impacted CBD stones.

- Citation: Yoo D. Laparoscopic choledocholithotomy and transductal T-tube insertion with indocyanine green fluorescence imaging and laparoscopic ultrasound: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(29): 7193-7199

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i29/7193.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i29.7193

Treatment options for choledocholithiasis include endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), with or without endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), and operative choledocholithotomy. ERCP has been considered the first-line treatment for choledocholithiasis because it has shown a high success rate (90%-100%) for common bile duct (CBD) stones[1,2]. However, the success rate of stone removal in patients with large stones is lower (68%-87.6%). The post-procedure complication rate, including pancreatitis, cholangitis, and bleeding, was reported to be 5%-10%, and the mortality rate was 0.2%-0.5%[2,3]. Also, the physiological function of the sphincter of Oddi can be destroyed by EST, and functional recovery is impossible after this procedure[4-7]. PTC is usually reserved for patients in whom ERCP cannot be performed safely, such as patients with impossible ampullary cannulation.

Traditionally, choledocholithiasis that could not be treated by ERCP or PTC has been managed by open choledocholithotomy, even after laparoscopic surgery was adopted in the hepatobiliary surgery field, because of the technical challenges involved[4,8,9]. However, advances in laparoscopic skills and technology have allowed surgeons to perform laparoscopic choledocholithotomy in patients with choledocholithiasis[8]. Several recent studies have also shown laparoscopic choledocholithotomy to be safe and feasible for these patients[4-7].

Many surgeons were reluctant to try laparoscopic choledochotomy in the early period of laparoscopic surgery because of the anticipated difficulties in patients with large CBD stones who could not be treated by laparoscopic transcystic CBD exploration[8,9]. Even in this era of minimally invasive surgery, laparoscopic choledochotomy for large impacted CBD stones is still a very challenging procedure because of the technical difficulty and possibility of postoperative complications, such as bile duct injury, which can result in diversion surgery (e.g., choledochojejunostomy).

In this case, we performed laparoscopic choledocholithotomy with transductal choledochotomy and T-tube insertion for large impacted CBD stones using indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence imaging and intraoperative ultrasound. As this report was based on the retrospective analysis of de-identified patient data and did not involve any interventions or interactions, it was exempt from institutional review board review.

A 71-year-old man visited our outpatient clinic due to right upper quadrant pain and jaundice.

The patient had right upper quadrant pain.

The patient’s medical history included paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus.

The patient had no previous history of tuberculosis, hepatitis, or allergies. He also had no history of abdominal surgery.

His abdomen was soft and flat, and mild tenderness was observed on the right upper quadrant.

The patient was admitted to our center for further examinations. The total serum bilirubin concentration was 5.5 mg/dL, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentrations were 60 and 81 U/L, respectively. The gamma-GTP concentration was 619 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase was 351 U/L. The C-reactive protein concentration was 6.56 mg/dL. Complete blood count and electrolyte values were within normal limits. The carbohydrate antigen 19-9 level was 251.5 U/mL.

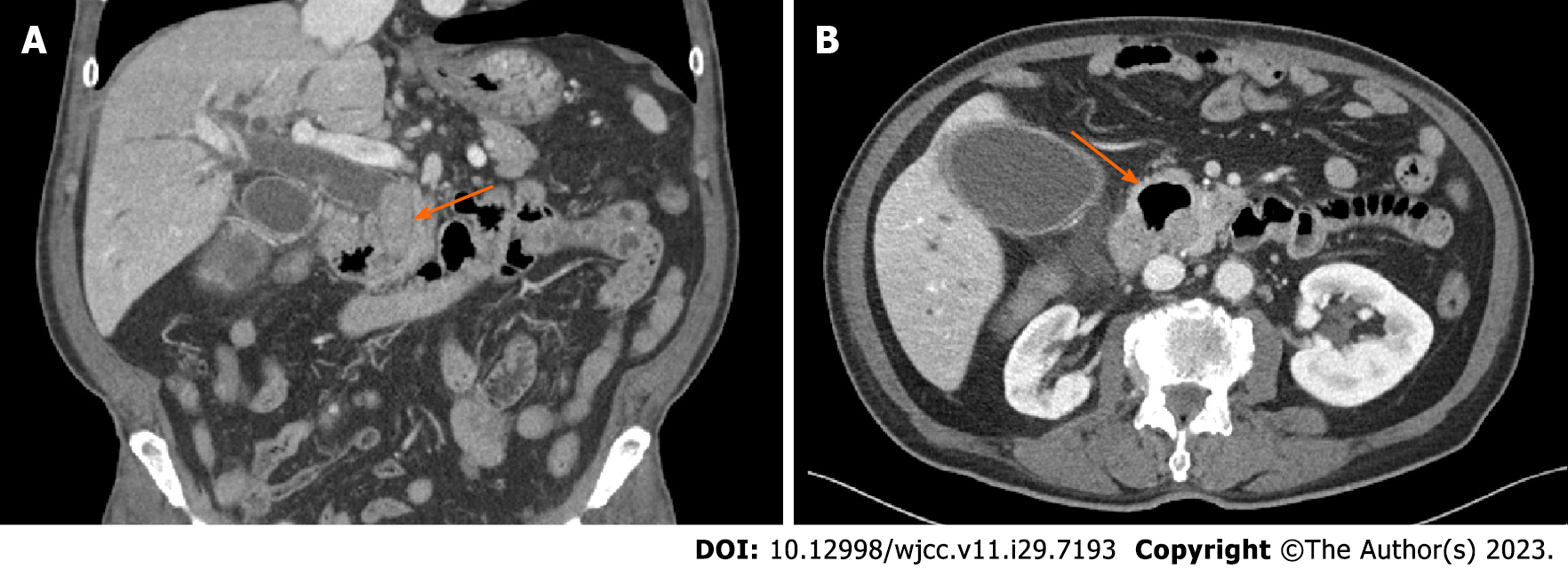

The patient underwent abdominal computed tomography (CT), in which one large stone (45 mm × 20 mm) impacting the distal CBD and another stone (20 mm × 15 mm) in the middle CBD were found (Figure 1A). The diameter of the CBD was 24 mm. Gallbladder (GB) stones with tensile distension of the GB and diffuse wall thickening were also noted on the CT scan.

Initially, we planned to perform ERCP first, followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The gastroenterologist tried ERCP to treat the stones but failed due to their large sizes and the presence of a large duodenal diverticulum (Figure 1B). The success rate of ERCP is low, and the complication rate is high when the papilla is located close to a periampullary diverticulum[10,11]. However, the gastroenterologist successfully inserted a plastic stent into the CBD. The total serum bilirubin level decreased to 1.7 mg/dL, and the AST and ALT levels were 26 and 44 U/L, respectively. The patient was transferred to the hepatobiliary pancreatic surgery department. We planned laparoscopic choledocholithotomy with cholecystectomy and transductal T-tube insertion.

Large-sized impacted CBD stones.

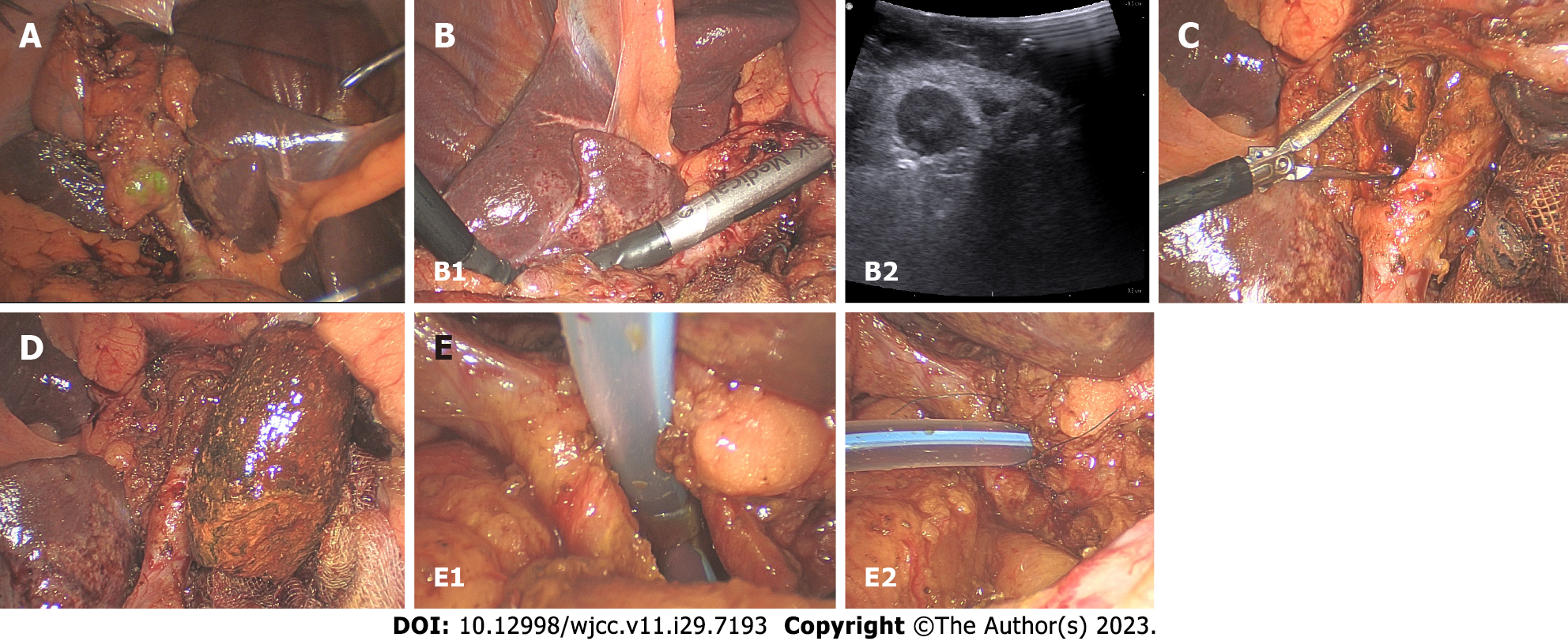

Five trocars were inserted during surgery, including one multilumen port (Glove portTM, Nelis Medical; Bucheon-si, South Korea) in the right upper quadrant (Figure 2). A near-infrared ICG fluorescence scope (10 mm, 30° scope; Stryker, MI, United States) was used to detect and expose the supraduodenal CBD more accurately. The near-infrared ICG fluorescence scope effectively showed the exact anatomy of the biliary tree and dilatation of the CBD in light green color during the surgery. After ligation of the cystic artery, we sutured the GB to the anterior abdominal wall with a barbed suture (StratafixTM; Johnson and Johnson Company, New Brunswick, NJ, United States) for traction and straightening of the CBD (Figure 3A). Then the location, size, and shape of the stones were detected using laparoscopic intraoperative ultrasound (Figure 3B). Surgical gauze was located at the right entrance of the foramen of Winslow to prevent the stones from slipping into the lesser sac. Next, the CBD was opened with a 2-cm-sized vertical incision. After irrigating several times, two CBD stones were removed with the Endo BabcockTM (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, United States) (Figure 3C and D). A choledochoscope was used to explore whether stones remained in the CBD. A T-tube was inserted and removed through the right upper quadrant trocar site. CBD closure around the T-tube insertion site was performed with nonabsorbable monofilament 5-0 interrupted sutures (Figure 3E). The near-infrared ICG fluorescence scope confirmed that there was no bile leakage from the suture site. Possible injury to the other site of the bile duct was checked, and no injury was found.

The patient had no postoperative complications. On the third postoperative day, the total serum bilirubin level was decreased to 1.1 mg/dL, and the AST and ALT levels were 13 and 12 U/L, respectively. After 2 mo, cholangiography was done through the T-tube, and remnant sludge and small stones were found and removed through a choledochoscope by a gastroenterologist.

No standard treatment exists for large CBD stones. Many authors defined a stone larger than 15-28 mm in diameter as a large CBD stone and reported low removal success rates with ERCP (68%-87.6%)[2,3]. Although open CBD exploration has been traditionally performed for large CBD stones, laparoscopic choledocholithotomy has become increasingly popular with the perfection of laparoscopic skills and the development of laparoscopic instruments[12,13].

At present, laparoscopic choledocholithotomy can be divided into two approaches: transcystic and transcholedochal[14]. The transcystic approach was preferred in many studies because it is less invasive and technically easy to perform[14,15]. However, this approach has limitations because it cannot be performed in patients with variations in the cystic duct, friable cystic duct, very large-sized CBD stones, and impacted distal CBD stones[8,14,16-19]. The size of the stone is an especially important risk factor in the failure of the transcystic approach, and the failure rate of the approach increases when the size of the stone is larger than the cystic duct diameter or over 5 mm[8,19]. The transcholedochal approach is done by laparoscopic choledochotomy and requires advanced skills in laparoscopic surgery. However, it can be performed regardless of the location of the CBD stone and is possible even for sizable stones.

Since Deaver et al first used and reported on the modified T-tube drain in 1904, transductal T-tube drain insertion after choledocholithotomy (open or laparoscopy) has been commonly used worldwide[4,20]. The transductal T-tube enables efficient postoperative decompression of the CBD and can decrease the possibility of bile leakage caused by high intraductal pressure[8]. Postoperative cholangiography can be done through the transductal T-tube, and the percutaneous removal of residual stones with a choledochoscope is also possible if tract maturation is completed after 4-8 wk post-surgery[8,17,21]. However, laparoscopic transductal T-tube insertion needs high skillfulness in laparoscopic manipulation and suturing. Postoperative complications, such as bile leakage or tube dislodgement, can occur in the case of incomplete fixation suturing around the T-tube insertion site.

ICG fluorescence guidance during laparoscopic surgery has been used in laparoscopic cholecystectomy[22-24]. ICG is a water-soluble molecule and binds to protein after intravenous administration[23]. It is exclusively metabolized by the liver and excreted primarily through the biliary system[23]. Because ICG fluorescence provides improved visualization of the biliary system, it also has many advantages in laparoscopic choledocholithotomy[22,24]. Since the location of the choledochotomy is very important for laparoscopic choledocholithotomy, ICG fluorescence guidance enables easier exposure of the supraduodenal CBD and helps to identify the choledochotomy site more accurately[22]. ICG fluorescence can also be used to confirm the secure closure of the choledochotomy site to prevent postoperative bile leakage[22]. Although adverse reactions to ICG can occur, the adverse reaction rate is 0.2% to 0.34%, and the allergic reaction rate is approximately 0.05%[25-27]. Also, the cost of a 10 mL vial of ICG is approximately $80, so the cost is not burdensome compared to its efficacy[28].

Laparoscopic intraoperative ultrasound has been used in laparoscopic biliary surgery in a variety of fields since its introduction[29-31]. Several studies have reported that laparoscopic intraoperative ultrasound can be used as an alternative to magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography or intraoperative cholangiography[29,30]. With the aid of laparoscopic ultrasound, surgeons can detect the CBD stone’s exact location, size, shape, and number. It helps to decide the accurate level of choledochotomy and the CBD incision size. While ICG fluorescence can show the exact anatomy of the biliary tree in superficial depth, deep structures can be detected by laparoscopic ultrasound. The detection of bile leakage is one of the unique features of ICG fluorescence guidance, whereas laparoscopic ultrasound provides a way to check the flow in vascular structures using the Doppler mode.

In our case, the patient had two CBD stones, including a very large-sized stone (45 mm). The larger stone was impacted in the distal CBD. He also had a large duodenal diverticulum near the ampulla of Vater, so endoscopic removal of the stone was almost impossible. Therefore, a laparoscopic transcholedochal approach was decided preoperatively. During surgery, the level and size of the choledochotomy were decided with the aid of ICG fluorescence guidance and laparoscopic intraoperative ultrasound. Although the large stone was not broken during surgery, some fragments were found in the distal CBD intraoperatively. Therefore, transductal T-tube insertion was performed. Choledochoscopic removal of remnant stones was performed after 8 weeks, and no postoperative complications occurred.

Laparoscopic choledocholithotomy by the transcholedochal approach and transductal T-tube insertion with ICG fluorescence imaging and laparoscopic ultrasound are safe and feasible options for patients with very large-sized and impacted CBD stones.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sun HL, China; Vyshka G, Albania S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Rieger R, Wayand W. Yield of prospective, noninvasive evaluation of the common bile duct combined with selective ERCP/sphincterotomy in 1390 consecutive laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:6-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Stefanidis G, Christodoulou C, Manolakopoulos S, Chuttani R. Endoscopic extraction of large common bile duct stones: A review article. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:167-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ, Lande JD, Pheley AM. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1689] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Hori T. Comprehensive and innovative techniques for laparoscopic choledocholithotomy: A surgical guide to successfully accomplish this advanced manipulation. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:1531-1549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Gu AD, Li XN, Guo KX, Ma ZT. Comparative evaluation of two laparoscopic procedures for treating common bile duct stones. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011;59:159-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Otani T, Yokoyama N, Sato D, Kobayashi K, Iwaya A, Kuwabara S, Yamazaki T, Matsuzawa N, Saito H, Katayanagi N. Safety and efficacy of a novel continuous incision technique for laparoscopic transcystic choledocholithotomy. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2017;10:282-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhou Y, Zha WZ, Wu XD, Fan RG, Zhang B, Xu YH, Qin CL, Jia J. Three modalities on management of choledocholithiasis: A prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2017;44:269-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhan X, Wang Y, Zhu J, Lin X. Laparoscopic Choledocholithotomy With a Novel Articulating Forceps. Surg Innov. 2016;23:124-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kitano S, Bandoh T, Yoshida T, Shuto K. Transcystic C-tube Drainage Following Laparoscopic Common Bile Duct Exploration. Surg Technol Int. 1994;3:181-186. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Altonbary AY, Bahgat MH. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in periampullary diverticulum: The challenge of cannulation. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8:282-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vaira D, Dowsett JF, Hatfield AR, Cairns SR, Polydorou AA, Cotton PB, Salmon PR, Russell RC. Is duodenal diverticulum a risk factor for sphincterotomy? Gut. 1989;30:939-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Grubnik VV, Tkachenko AI, Ilyashenko VV, Vorotyntseva KO. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration versus open surgery: comparative prospective randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2165-2171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ghazal AH, Sorour MA, El-Riwini M, El-Bahrawy H. Single-step treatment of gall bladder and bile duct stones: a combined endoscopic-laparoscopic technique. Int J Surg. 2009;7:338-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hongjun H, Yong J, Baoqiang W. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: choledochotomy versus transcystic approach? Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015;25:218-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhu T, Lin H, Sun J, Liu C, Zhang R. Primary duct closure versus T-tube drainage after laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: a meta-analysis. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2021;22:985-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lyass S, Phillips EH. Laparoscopic transcystic duct common bile duct exploration. Surg Endosc. 2006;20 Suppl 2:S441-S445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tinoco R, Tinoco A, El-Kadre L, Peres L, Sueth D. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. Ann Surg. 2008;247:674-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chiarugi M, Galatioto C, Decanini L, Puglisi A, Lippolis P, Bagnato C, Panicucci S, Pelosini M, Iacconi P, Seccia M. Laparoscopic transcystic exploration for single-stage management of common duct stones and acute cholecystitis. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:124-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Strömberg C, Nilsson M, Leijonmarck CE. Stone clearance and risk factors for failure in laparoscopic transcystic exploration of the common bile duct. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1194-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Apalakis A. An experimental evaluation of the types of material used for bile duct drainage tubes. Br J Surg. 1976;63:440-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tokumura H, Umezawa A, Cao H, Sakamoto N, Imaoka Y, Ouchi A, Yamamoto K. Laparoscopic management of common bile duct stones: transcystic approach and choledochotomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:206-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gadiyaram S, Thota RK. Near-infrared fluorescence guided laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the spectrum of complicated gallstone disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e31170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ambe PC, Plambeck J, Fernandez-Jesberg V, Zarras K. The role of indocyanine green fluoroscopy for intraoperative bile duct visualization during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an observational cohort study in 70 patients. Patient Saf Surg. 2019;13:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Serban D, Badiu DC, Davitoiu D, Tanasescu C, Tudosie MS, Sabau AD, Dascalu AM, Tudor C, Balasescu SA, Socea B, Costea DO, Zgura A, Costea AC, Tribus LC, Smarandache CG. Systematic review of the role of indocyanine green near-infrared fluorescence in safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23:187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hope-Ross M, Yannuzzi LA, Gragoudas ES, Guyer DR, Slakter JS, Sorenson JA, Krupsky S, Orlock DA, Puliafito CA. Adverse reactions due to indocyanine green. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:529-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 442] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kim M, Lee S, Park JC, Jang DM, Ha SI, Kim JU, Ahn JS, Park W. Anaphylactic Shock After Indocyanine Green Video Angiography During Cerebrovascular Surgery. World Neurosurg. 2020;133:74-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Obana A, Miki T, Hayashi K, Takeda M, Kawamura A, Mutoh T, Harino S, Fukushima I, Komatsu H, Takaku Y. Survey of complications of indocyanine green angiography in Japan. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;118:749-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Manny TB, Krane LS, Hemal AK. Indocyanine green cannot predict malignancy in partial nephrectomy: histopathologic correlation with fluorescence pattern in 100 patients. J Endourol. 2013;27:918-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Dili A, Bertrand C. Laparoscopic ultrasonography as an alternative to intraoperative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:5438-5450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Luo Y, Yang T, Yu Q, Zhang Y. Laparoscopic Ultrasonography Versus Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography in Laparoscopic Surgery for Symptomatic Cholelithiasis and Suspected Common Bile Duct Stones. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:1143-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Atstupens K, Mukans M, Plaudis H, Pupelis G. The Role of Laparoscopic Ultrasonography in the Evaluation of Suspected Choledocholithiasis. A Single-Center Experience. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |