Published online Oct 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i29.7170

Peer-review started: June 26, 2023

First decision: August 16, 2023

Revised: August 25, 2023

Accepted: September 22, 2023

Article in press: September 22, 2023

Published online: October 16, 2023

Processing time: 107 Days and 0.5 Hours

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a common aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL), accounting for 30%-40% of adult NHLs. This report aims to explore the efficacy and safety of rituximab combined with Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKis) in the treatment of elderly patients with DLBCL.

The clinical data of two elderly patients with DLBCL who received rituximab combined with BTKi in our hospital were retrospectively analyzed, and the literature was reviewed. The patients were treated with chemotherapy using the R-miniCHOP regimen for two courses. Then, they received rituximab in combination with BTKi.

The treatment experience in these cases demonstrates the potential efficacy of rituximab combined with BTKi to treat elderly DLBCL patients, thus providing a new treatment strategy.

Core Tip: The clinical data of two elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) who received rituximab combined with Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor (BTKi) in our hospital were retrospectively analyzed, and the literature was reviewed. The patients were treated with chemotherapy using the R-miniCHOP regimen for 2 courses. Then, they received rituximab in combination with BTKi. The treatment experience in these patients demonstrates the potential efficacy of rituximab combined with BTKi to treat elderly DLBCL patients, thus providing a new treatment strategy.

- Citation: Zhang CJ, Zhao ML. Rituximab combined with Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor to treat elderly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(29): 7170-7178

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i29/7170.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i29.7170

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL), representing 20%-30% of NHLs, and mainly affecting patients with a median age of 66–70 years[1,2]. The incidence and mortality of DLBCL increase with age. It was found that the reason for the poor prognosis of elderly DLBCL patients is that these patients cannot complete standard treatment due to decreased physical function, increased complications, and impaired organ function. Moreover, there are more adverse biological characteristics in elderly DLBCL patients, so the prognosis of elderly DLBCL is often poor[3]. Therefore, the treatment of elderly DLBCL patients requires individualized selection, and safety and effectiveness must be considered to achieve reasonable stratified treatment. We here retrospectively analyze the diagnosis and treatment of two elderly DLBCL patients treated with rituximab combined with Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi), which provided a reference for the treatment of elderly DLBCL patients.

Case 1: The patient complained of right backside and leg pain.

Case 2: The patient complained of epigastric pain.

Case 1: On April 10, 2021, an 86-year-old male patient visited our hospital due to right backside and leg pain for 2 wk. Right iliac bone puncture pathology showed DLBCL [non-germinal center B cell (GCB)]. Immunohistochemistry showed the following: CD20+, PAX5+, CD10-, Bcl-6+, MUM1+, C-myc+ (approximately 40%), Ki-67+ (80%), CD3-, CD5-, CD30-, AE1/AE3-, and SALL4-. Molecular in situ hybridization was EBER-negative.

Case 2: On May 21, 2021, an 87-year-old female patient attended our hospital due to epigastric pain for 1 wk. On May 23, 2021, the gastroscopy showed a giant ulcer in the stomach. Pathology revealed DLBCL (GCB). Immunohistochemistry showed the following: CD20+, PAX5+, CD3-, CD5-, Ki-67+ (90%), CD10+ (5%), BcL-2+ (30%), Bcl-6+ (80%), C-Myc+ (70%), MUM1-, CyclinD1-, CD21-, CD23-, AE1/AE3-, CK19-, and EBER-.

Both patients had no family history and no specific social history.

No personal or family history was available.

Case 1: Physical examination showed that the neck, armpit and groin were enlarged, with no palpable organomegaly or cutaneous lesions.

Case 2: Physical examination showed no palpable lymph nodes, organomegaly, or cutaneous lesions.

The peripheral blood and biochemical parameters (liver and renal function and serum lactate dehydrogenase level) were all within normal limits. Bone marrow smear and biopsy did not show evidence of lymphoma cell involvement.

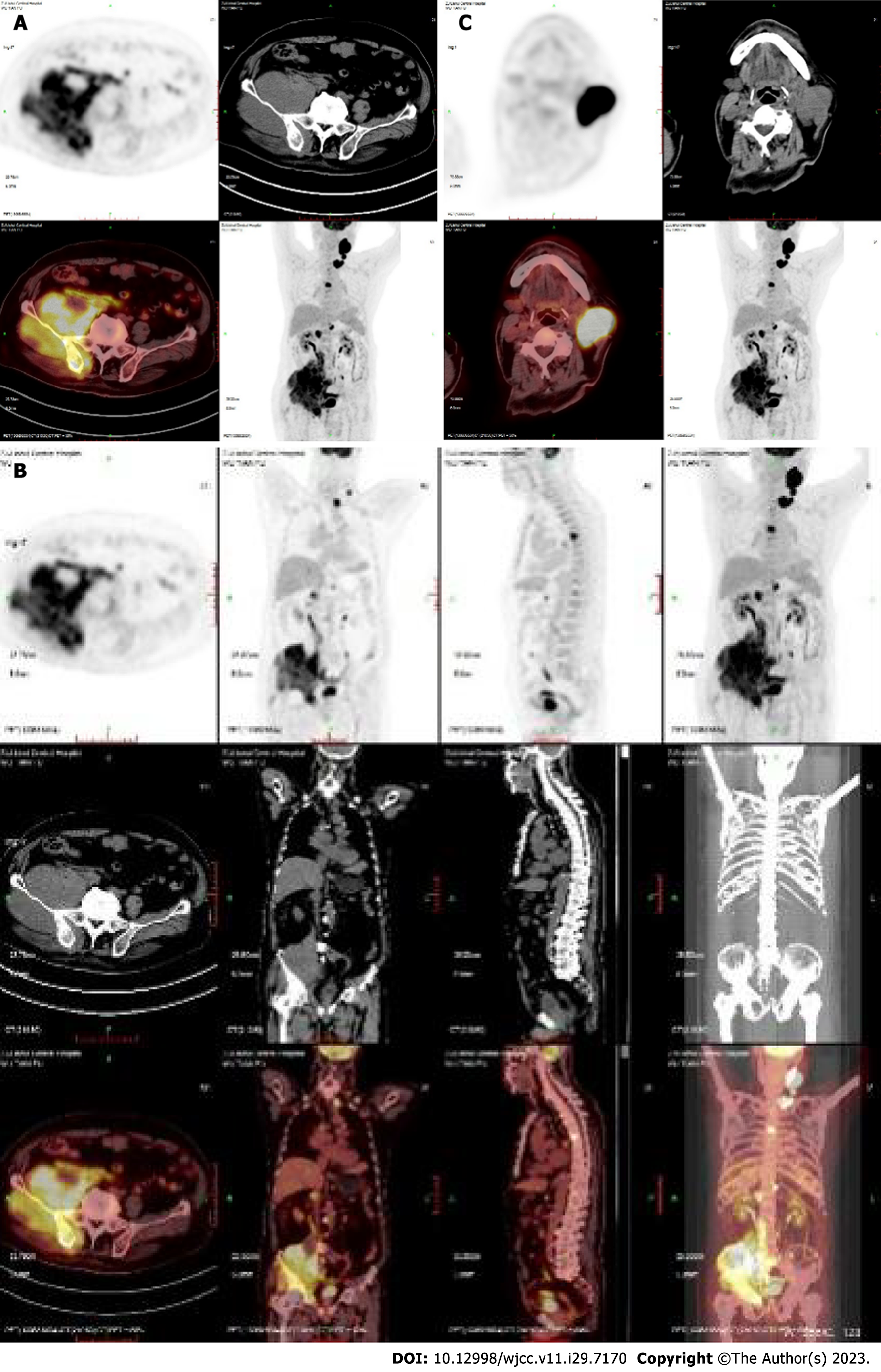

Case 1: On April 12, 2021, positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) showed multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the left neck and left supraclavicular region, significantly increased 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose metabolism and a high standard uptake value (SUV) with a Deauville score of 22.3. The bone density of the right ilium increased unevenly, with an irregular soft tissue mass involving the right side of the sacrum and the right acetabulum, with unclear borders (approximately 12.8 cm × 11.3 cm) and an uptake value (SUV) with a Deauville score of 11.9. Enlarged lymph nodes were noted in the right parailiac, retroperitoneal, and perimesenteric vessels, and the uptake value (SUV) had a Deauville score of 10.0 (Figure 1).

Case 2: On May 22, 2021, PET-CT showed extensive irregular thickening of the stomach wall from the cardia, and the stomach body was accompanied by multiple ulcers, with an uptake value (SUV) and a Deauville score of 23.2 (Figure 2).

Based on the above findings, the clinical diagnosis in both cases was DLBCL, stage IVB.

Case 1: After diagnosis, the patient was treated with chemotherapy using the R-miniCHOP regimen for two cycles (rituximab 0.6 g d0, ifosfamide 1 g d1-2, liposomal doxorubicin 20 mg d1, vindesine 4 mg d1, dexamethasone 5 mg d1-5). Efficacy evaluation was assessed as partial remission (PR). The patient developed severe pulmonary infection after chemotherapy. Then, an R-R regimen was administered for 6 cycles (rituximab 0.6 g d0, ibrutinib 160 mg bid po).

Case 2: On May 28, 2021, the patient was treated with rituximab and dexamethasone (rituximab 0.4 g d0, dexamethasone 5 mg d1-5). On June 23, 2021, the R-miniCHOP regimen was administered for two cycles (rituximab 0.4 g d0, cyclophosphamide 300 mg d1, liposomal doxorubicin 15 mg d1, vindesine 4 mg d1, dexamethasone 5 mg d1-5). The patient could not continue the chemotherapy because of side effects. An R-R regimen was then administered for three cycles (rituximab 0.4 g d0, ibrutinib 160 mg bid po).

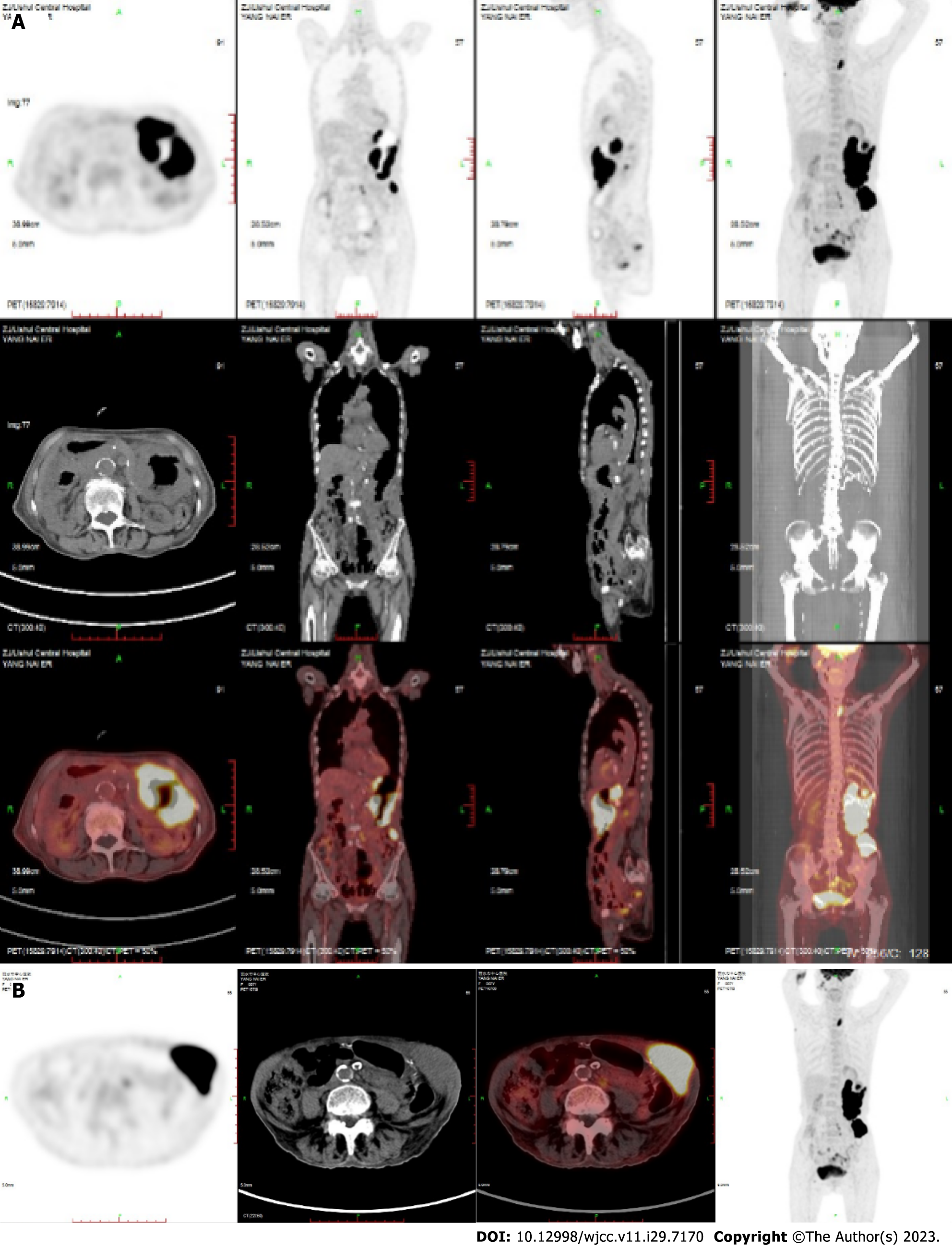

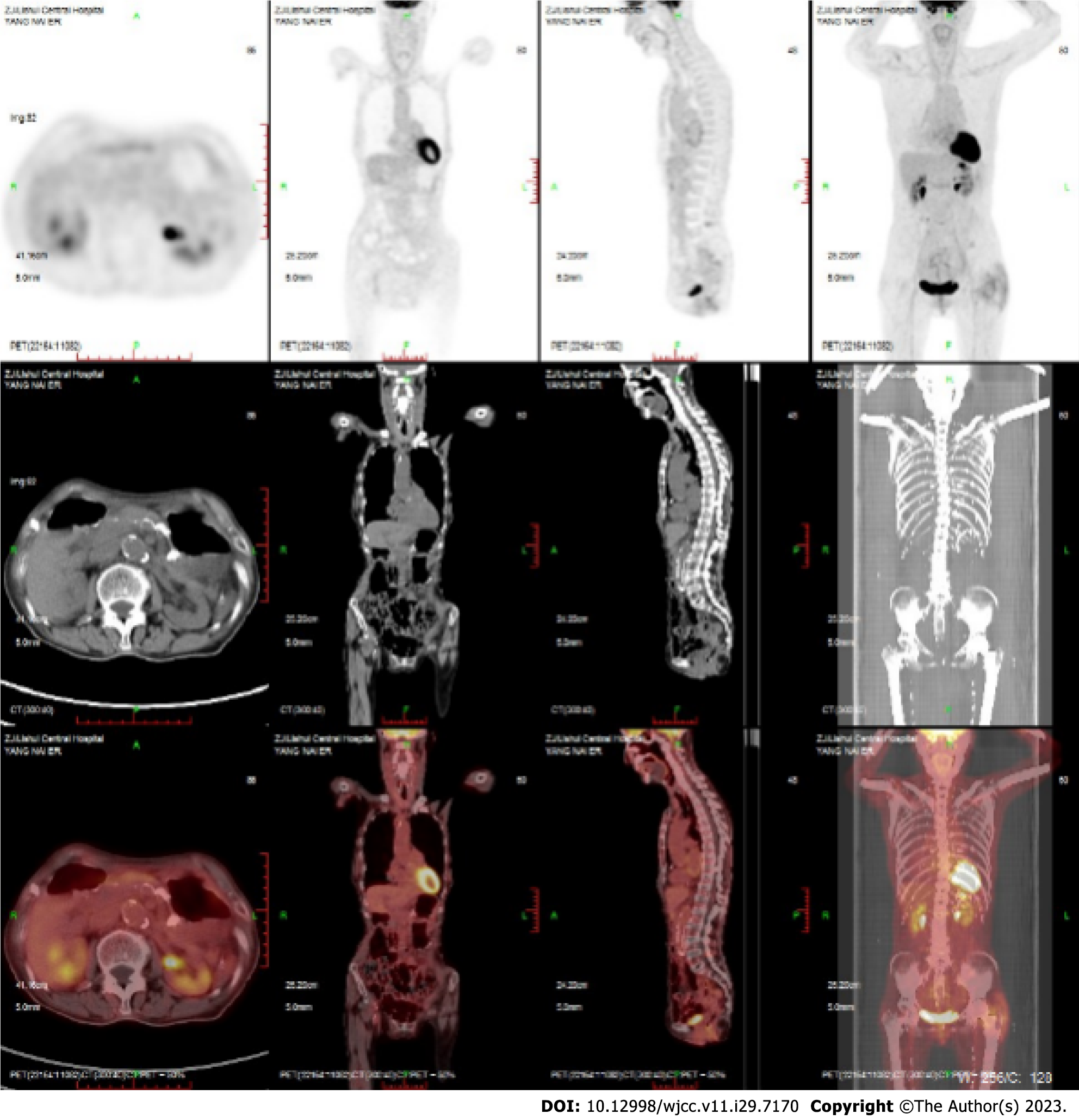

Case 1: After treatment, PET-CT showed complete remission of lymphoma (Figure 3). Maintenance therapy with zeputinib was continued.

Case 2: PETCT showed complete remission of lymphoma (Figure 4). Maintenance therapy with zeputinib was continued.

DLBCL is the most common subtype of NHL, representing 20%-30% of NHLs, with a median age of onset of 66–70 years[1,2]. The incidence and mortality of DLBCL increase with age. The prognosis of elderly DLBCL is poor as the patients are unable to complete standard treatment due to decreased physical function, more complications, and impaired organ function. Moreover, there are more adverse biological characteristics of elderly DLBCL patients, so the prognosis of elderly DLBCL is often poor[3]. Therefore, the treatment of elderly DLBCL patients needs to be individualized, and safety and effectiveness must be considered to achieve reasonable stratified treatment. We retrospectively analyzed the diagnosis and treatment of elderly DLBCL patients treated with rituximab combined with BTKi. Our experience provides a reference for the treatment of elderly DLBCL patients.

DLBCL is an extremely aggressive B-cell lymphoma. It has obvious heterogeneity and drug resistance and has a variable prognosis[4]. DLBCL patients aged over 80 years are defined as ultra-aged DLBCL patients, and there are few reports on them. Ultra-aged DLBCL patients cannot tolerate standard-dose chemotherapy due to various complications and organ dysfunction. The biological characteristics of ultra-aged DLBCL patients also underlie the poor prognosis of the disease, which is characterized by poor response to chemotherapy and easy relapse. The expression of complex karyotypes, poor prognosis genes, and multidrug resistance genes also prevent elderly DLBCL patients from achieving satisfactory results[5]. The treatment strategy of ultra-aged DLBCL patients is still controversial. Ultra-aged patients have less chance of having an autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and traditional treatment has poor efficacy for elderly patients. Therefore, relapse-free survival and overall survival (OS) remain low in these patients.

The current standard first-line treatment for DLBCL is the R-CHOP regimen, which can significantly improve OS and progression-free survival (PFS). With this regimen, 30%-40% of patients progress to refractory relapsing DLBCL, leading to a poor prognosis[6]. One study showed that after R-miniCHOP treatment, the overall response rate (ORR) of elderly patients was 63%, with a complete remission rate of 56% and a PR rate of 7%. The main cause of death of patients was tumor progression, and most adverse events occurred in patients within two treatment cycles[7]. Hounsome et al[8] found that among DLBCL patients aged ≥ 80 years, there was no significant difference in the 3-year OS rate between R-miniCHOP and R-CHOP, both of which resulted in an approximate rate of 54%. Our two elderly patients (aged ≥ 85 years) started to receive the R-miniCHOP regimen. However, it was not effective, and severe myelosuppression and lung infection after chemotherapy require adjustment of the treatment regimen.

With the study of biological characteristics and targeted drugs for DLBCL, a variety of new drugs have appeared continuously. BTKi is a new targeted drug that can inhibit the upstream signaling pathway of the B-cell receptor (BCR), thereby inhibiting NF-κB kinase and leading to DLBCL cell death[9]. BTK is a signaling molecule downstream of the BCR[10,11]. It is a key effector molecule that is involved in all aspects of B-cell development and many signaling pathways of B cells, including chemokine receptors and Toll-like receptors[12]. BTK is essential for the survival of various B-cell malignancies, such as DLBCL, mantle cell lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, which makes BTK inhibitors valuable drugs to treat B-cell malignancies[13-15]. BTKi has shown positive efficacy in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma, but there are few reports on the treatment of invasive lymphoma. A clinical trial reported that 80 relapsed/refractory DLBCL patients treated with BTKi had a median age of 60 years, an ORR of 5%, and median overall survival and PFS of 6.41 and 1.64 mo, respectively, and patients with non-GCB had higher rates of partial response and complete response in the GCB subtype than in the GCB subtype[16].

The most common adverse effect of BTKi is cardiotoxic manifestations, with atrial fibrillation (AF) being the most common type[17]. Wiczer et al[18] found that AF is usually controllable with continuous BTKi and that the risk factors for supraventricular arrhythmia after BTKi treatment include advanced age, male sex, a history of supraventricular arrhythmia, hypertension and preexisting heart disease. Wang et al[19] found that half of the patients who received BTKi had bleeding events. The most common bleeding manifestations are subcutaneous or mucosal, including nasal bleeding, skin ecchymosis, hematuria, etc., and the incidence of fatal bleeding is less than 1%. Other adverse reactions also include infection, diarrhea, and hematological toxicity[20,21]. Compared with traditional chemotherapy, BTKi is safer. In the process of treatment, we should closely monitor the population with these high-risk factors and actively treat symptoms, and the adverse reactions[22]. In this paper, two superelderly patients treated with rituximab combined with BTKi achieved good outcomes, and no serious adverse reactions occurred.

For ultra-aged patients, BTKi combined with rituximab is safe and reliable. They cannot tolerate chemotherapy, so new treatment ideas are needed. Our center will continue to treat older patients with DLBCL and explore the feasibility of BTKi plus rituximab in an attempt to find new treatment strategies for this population.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shahriari M, Iran S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: Ma JY P-Editor: Lin C

| 1. | Gang AO, Pedersen MØ, Knudsen H, Lauritzen AF, Pedersen M, Nielsen SL, Brown P, Høgdall E, Klausen TW, Nørgaard P. Cell of origin predicts outcome to treatment with etoposide-containing chemotherapy in young patients with high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:2039-2046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Smith A, Howell D, Patmore R, Jack A, Roman E. Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub-type: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1684-1692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 403] [Cited by in RCA: 485] [Article Influence: 34.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Crump M, Neelapu SS, Farooq U, Van Den Neste E, Kuruvilla J, Westin J, Link BK, Hay A, Cerhan JR, Zhu L, Boussetta S, Feng L, Maurer MJ, Navale L, Wiezorek J, Go WY, Gisselbrecht C. Outcomes in refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the international SCHOLAR-1 study. Blood. 2017;130:1800-1808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 724] [Cited by in RCA: 1188] [Article Influence: 148.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Thieblemont C, Bernard S, Meignan M, Molina T. Optimizing initial therapy in DLBCL. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2018;31:199-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pasqualucci L, Dalla-Favera R. Genetics of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2018;131:2307-2319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, Lepeu G, Plantier I, Castaigne S, Lefort S, Marit G, Macro M, Sebban C, Belhadj K, Bordessoule D, Fermé C, Tilly H. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood. 2010;116:2040-2045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 884] [Cited by in RCA: 1143] [Article Influence: 76.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yamasaki S, Matsushima T, Minami M, Kadowaki M, Takase K, Iwasaki H. Clinical impact of comprehensive geriatric assessment in patients aged 80 years and older with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma receiving rituximab-mini-CHOP: a single-institute retrospective study. Eur Geriatr Med. 2022;13:195-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hounsome L, Eyre TA, Ireland R, Hodson A, Walewska R, Ardeshna K, Chaganti S, McKay P, Davies A, Fox CP, Kalakonda N, Fields PA. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in patients older than 65 years: analysis of 3 year Real World data of practice patterns and outcomes in England. Br J Cancer. 2022;126:134-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tanaka S, Baba Y. B Cell Receptor Signaling. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1254:23-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rip J, de Bruijn MJW, Appelman MK, Pal Singh S, Hendriks RW, Corneth OBJ. Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Drives Btk-Mediated Autoimmune Disease. Front Immunol. 2019;10:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang Y, Zhang LL, Champlin RE, Wang ML. Targeting Bruton's tyrosine kinase with ibrutinib in B-cell malignancies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;97:455-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pal Singh S, Dammeijer F, Hendriks RW. Role of Bruton's tyrosine kinase in B cells and malignancies. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 495] [Article Influence: 70.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gabizon R, London N. A Fast and Clean BTK Inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2020;63:5100-5101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bond DA, Woyach JA. Targeting BTK in CLL: Beyond Ibrutinib. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2019;14:197-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zi F, Yu L, Shi Q, Tang A, Cheng J. Ibrutinib in CLL/SLL: From bench to bedside (Review). Oncol Rep. 2019;42:2213-2227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wilson WH, Young RM, Schmitz R, Yang Y, Pittaluga S, Wright G, Lih CJ, Williams PM, Shaffer AL, Gerecitano J, de Vos S, Goy A, Kenkre VP, Barr PM, Blum KA, Shustov A, Advani R, Fowler NH, Vose JM, Elstrom RL, Habermann TM, Barrientos JC, McGreivy J, Fardis M, Chang BY, Clow F, Munneke B, Moussa D, Beaupre DM, Staudt LM. Targeting B cell receptor signaling with ibrutinib in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Nat Med. 2015;21:922-926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 713] [Cited by in RCA: 915] [Article Influence: 91.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Salem JE, Manouchehri A, Moey M, Lebrun-Vignes B, Bastarache L, Pariente A, Gobert A, Spano JP, Balko JM, Bonaca MP, Roden DM, Johnson DB, Moslehi JJ. Cardiovascular toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: an observational, retrospective, pharmacovigilance study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1579-1589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 534] [Cited by in RCA: 854] [Article Influence: 122.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wiczer TE, Levine LB, Brumbaugh J, Coggins J, Zhao Q, Ruppert AS, Rogers K, McCoy A, Mousa L, Guha A, Heerema NA, Maddocks K, Christian B, Andritsos LA, Jaglowski S, Devine S, Baiocchi R, Woyach J, Jones J, Grever M, Blum KA, Byrd JC, Awan FT. Cumulative incidence, risk factors, and management of atrial fibrillation in patients receiving ibrutinib. Blood Adv. 2017;1:1739-1748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang ML, Blum KA, Martin P, Goy A, Auer R, Kahl BS, Jurczak W, Advani RH, Romaguera JE, Williams ME, Barrientos JC, Chmielowska E, Radford J, Stilgenbauer S, Dreyling M, Jedrzejczak WW, Johnson P, Spurgeon SE, Zhang L, Baher L, Cheng M, Lee D, Beaupre DM, Rule S. Long-term follow-up of MCL patients treated with single-agent ibrutinib: updated safety and efficacy results. Blood. 2015;126:739-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Los-Arcos I, Aguilar-Company J, Ruiz-Camps I. Risk of infection associated with new therapies for lymphoproliferative syndromes. Med Clin (Barc). 2020;154:101-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, Robak T, Owen C, Ghia P, Bairey O, Hillmen P, Bartlett NL, Li J, Simpson D, Grosicki S, Devereux S, McCarthy H, Coutre S, Quach H, Gaidano G, Maslyak Z, Stevens DA, Janssens A, Offner F, Mayer J, O'Dwyer M, Hellmann A, Schuh A, Siddiqi T, Polliack A, Tam CS, Suri D, Cheng M, Clow F, Styles L, James DF, Kipps TJ; RESONATE-2 Investigators. Ibrutinib as Initial Therapy for Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2425-2437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1157] [Cited by in RCA: 1228] [Article Influence: 122.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kavoosi M, O'Reilly TE, Kavoosi M, Chai P, Engel C, Korz W, Gallen CC, Lester RM. Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Concentration-QTc Analysis of Tetrodotoxin: A Randomized, Dose Escalation Study in Healthy Adults. Toxins (Basel). 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |