Published online Oct 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i29.7043

Peer-review started: June 27, 2023

First decision: August 4, 2023

Revised: September 11, 2023

Accepted: September 22, 2023

Article in press: September 22, 2023

Published online: October 16, 2023

Processing time: 107 Days and 17.8 Hours

The study sought to understand the self-management strategies used by patients during the postponement of their total knee arthroplasty (TKA) procedure, as well as the associations between the length of waiting time, pain, and physical frailty and function. The study focused on individuals aged 50 years and above, as they are known to be more vulnerable to the negative impacts of delayed elective sur

To investigate the effects of COVID-19 pandemic on self-management, pain, and physical function in older adults awaiting TKA in Malaysia.

This cross-sectional study has the data of participants, who matched the criteria and scheduled for TKA for the first time, extracted from the TKA registry in the Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Hospital Canselor Tuanku Mukhriz. Data on pain status, and self-management, physical frailty, and instrumental activities daily living were also collected. Multiple linear regression analysis with a significant level of 0.05 was used to identify the association between waiting time and pain on physical frailty and functional performance.

Out of 180 had deferred TKA, 50% of them aged 50 years old and above, 80% were women with ethnic distribution Malay (66%), Chinese (22%), Indian (10%), and others (2%) respectively. Ninety-two percent of the participants took medication to manage their pain during the waiting time, while 10% used herbs and traditional supplements, and 68% did exercises as part of their osteoarthritis (OA) self-management. Thirty-six participants were found to have physical frailty (strength, assistance with walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and falls questionnaire score > 4) which accounted for 72%. Increased pain was associated with physical frailty with odds ratio, odds ratio (95% confidence interval): 1.46 (1.04-2.05). This association remained significant even after the adjustment accor

While deferring TKA during a pandemic is unavoidable, patient monitoring for OA treatment during the waiting period is important in reducing physical frailty, ensuring the older patients’ independence.

Core Tip: Prevalence of osteoarthritis (OA) increases with age and contributes to pain, physical inactivity, and mental distress, eventually resulting in high disease burden and low quality of life. As the last resort for late knee OA, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) aims to relieve knee pain by replacing knee joints’ articular surfaces. The emergence of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic had interrupted elective surgery and rehabilitation, including TKA for OA patients. The self-management strategies and impacts of delayed TKA may bring interesting insight. This study aimed to determine the associations of TKA waiting time and pain status with physical frailty and function among older patients.

- Citation: Mahdzir ANK, Mat S, Seow SR, Abdul Rani R, Che Hasan MK, Mohamad Yahaya NH. Self-management of osteoarthritis while waiting for total knee arthroplasty during the COVID-19 pandemic among older Malaysians. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(29): 7043-7052

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i29/7043.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i29.7043

Late December 2019, a viral infection, novel coronavirus which is known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was detected with cases emerging from Wuhan, China[1]. According to the World Health Organization, as of 20th October 2021, there had been more than 241 million confirmed cases around the world, with more than 4 million deaths reported. The first reported COVID-19 case in Malaysia was on 25th January 2020 with a history of close contact with an infected person in Singapore[2]. Due to the emergence of the pandemic, elective surgery and rehabilitation were interrupted. Hospitals were converted into COVID hospitals, and procedures and outpatients’ appointments were postponed or cancelled. Individuals with chronic conditions such as osteoarthritis (OA) may have been impacted by these circumstances.

The prevalence of OA increases with age, making it one of the most common joint complaints among older adults. OA is characterized with articular cartilage deterioration and persistent pain, the debilitating symptoms may cause reduce physical function, disability, poor quality of life and depression in long run[3]. As a disease of whole joint, there are multiple structural factors associated with OA. Nevertheless, pain generally becomes more intense and frequent as OA worsens[4]. With a global incidence of 203 cases per 10000 and 654.1 million knee OA cases reported worldwide in 2020, it’s an important issue to address[5]. For those with severe knee OA, who have not responded well to non-operative treatments, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) may be the only option available. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, TKA operations have been postponed and delayed globally, with data from low-middle income countries such as Malaysia not yet well studied[6]. In the United States, 30000 primary and 3000 revision total joint arthroplasty procedures were cancelled weekly and around 92.6% of primary total joint arthroplasty procedures were cancelled in Europe[7].

Our goal is to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected patients in need of TKA by examining the self-management practices they have adopted, as well as how these practices have influenced the relationship between waiting time, pain, physical frailty, and function in individuals over the age of 50 seeking TKA at the Hospital Canselor Tuanku Mukhriz (HCTM), which is a tertiary urban hospital in Kuala Lumpur.

This study used a cross-sectional survey design to examine the effects of surgical deferment on patient health status and self-management during the COVID-19 pandemic, using data from a TKA registry. Data was collected anonymously on patients who were waiting for elective TKA between January 2021 and May 2022, obtained from the Department of Orthopaedic at the HCTM in Malaysia which cater approximately 500000 Malaysian citizens who lived in the areas of Cheras, Ampang, Hulu Langat, Semenyih and Bangi. Patients with upcoming appointments for TKR surgery revision or had done TKR were excluded.

This study collected data on-site at the Department of Orthopaedic at the HCTM. The research had two phases: The first phase involved extracting data from the TKA registry, and the second phase involved conducting a survey on patients’ health status and self-management. Demographic information was also collected. Participants were contacted and provided with a consent form, and the survey questionnaires were distributed according to their preferences (e.g., online or paper-based). Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the UKM ethics committee (reference number: JEP-2022-105).

Number of deferrals and Waiting time pre and post COVID: The number of surgery deferrals and waiting times was obtained from the Department of Orthopaedic at the HCTM during pre- and post-COVID. Participants’ names and contact numbers in post covid were collected.

Demographic data and medical condition: Participants’ demographic data consisted of age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, living arrangement, education level, occupation, and duration of OA. Participants were asked about underlying medical conditions during the waiting time for TKA surgery.

Pain status: Pain intensity was assessed using the visual analog scale (VAS), which is a common tool in clinical settings, and is a Likert-scale that measures the intensity of pain felt by participants during the waiting period. On the VAS scale, 0 represents no pain, 5 represents moderate pain, and 10 represents the worst possible pain. In addition to VAS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) which is a knee-specific instrument developed to assess patients’ perceptions of their knee problems and conditions have also been used[8,9].

Physical frailty and physical function: The strength, assistance in walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and falls (SARC-F) questionnaires were used to identify physical frailty associated with sarcopenia based on the cardinal signs of sarcopenia. The SARC-F questionnaires assesses strength, ability to walk independently, ability to rise from a chair, ability to climb stairs and history of falls, which are known indicators of sarcopenia[10]. To evaluate physical function, the Lawton instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) Scale was used. The IADL Scale is a useful tool for measuring a person’s current level of functioning and identifying any changes over time. The scale measures eight domains of function, including, but not limited to, self-care and household management, communication, mobility, recreation and leisure, and household maintenance and management. The IADL Scale provides a comprehensive view of patients’ physical function and activities of daily living, useful for evaluating the impact of physical frailty or sarcopenia on patients’ quality of life[11].

Self-management: Self-management included the types of medication taken by participants and the exercise prescription, either through physiotherapy sessions (such as house call physiotherapy or online telehealth) or through self-directed exercises found on websites. Additionally, the study also examined the use of traditional medication by participants during the waiting period. Overall, the self-management data was collected to identify how patients were coping with their pain and physical limitations while they waited for their TKA.

Results from the survey questionnaire were analysed using the Statistical Products and Service Solution (SPSS) IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Descriptive analysis (means and percentages) was used to analyse the total number of surgery deferrals and the changes in waiting time of TKA, and to evaluate participants’ current underlying medical condition, development a medical condition, self-management (exercise and medication), and pain intensity felt during the waiting period. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to identify the association between waiting time and pain on physical frailty and functional performance among older patients waiting for TKA. The significance level was set at a P value of < 0.05. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Dr. Sumaiyah Mat from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, who is a holder of Master of Applied statistics.

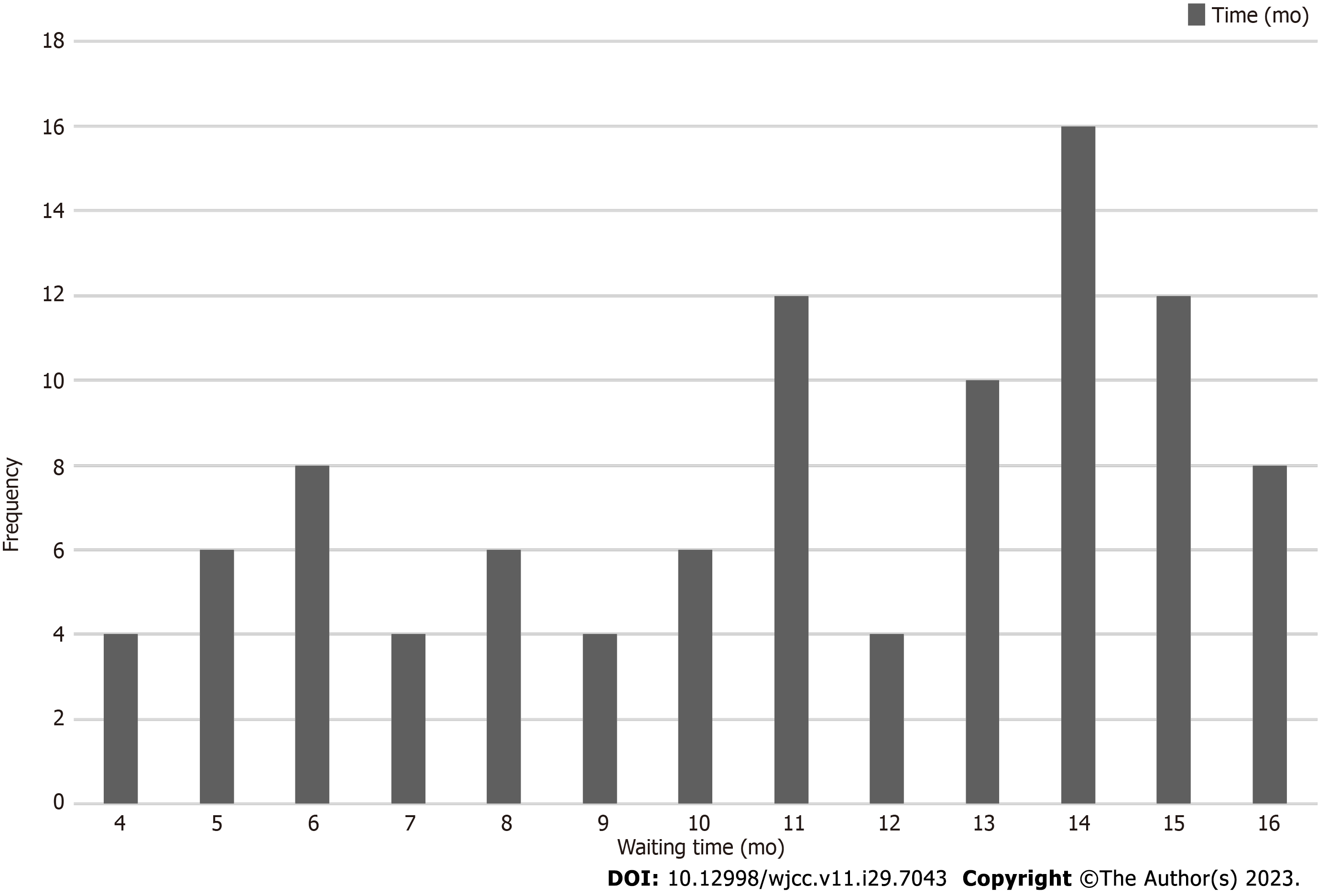

Out of the 180 patients who had deferred TKA, 50% were aged 50 years and older (Figure 1). Of the 50 participants successfully contacted, the mean age was 68.7 (SD 6.97). Half of the participants were waiting for TKA surgery for 12 mo or more. The highest waiting period among participants was 14 mo, with the lowest waiting times being four, seven, nine, and 12 mo (Figure 1).

Most of the included participants were female, with a total of 40 (80%) and belonged to the Malay ethnicity (66%), Chinese (22%), Indian (10%), and others (2%) respectively. Participants were mostly married, with 86% of them living with their spouses. 30 participants had pursued their studies at the tertiary level (30%) while 44% had finished secondary school, 20% at the primary school level, and 6% had not received any formal education. Most participants were retired, with 86% of them, while 8% were still working. The most common medical conditions presented among the participants were hypertension (70%), followed by hypercholesterolemia (44%), and diabetes (40%). The percentage of the duration of OA was the same for durations below one year and within one to three years, with 42%, while participants who had been diagnosed with OA for more than three years were 16% (Table 1).

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 68.7 ± 6.97 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 10 (20) |

| Female | 40 (80) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Malay | 33 (66) |

| Chinese | 11 (22) |

| Indian | 5 (10) |

| Others | 1 (2) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 1 (2) |

| Married | 43 (86) |

| Divorce | 6 (12) |

| Living arrangement | |

| Alone | 2 (4) |

| With husband/wife | 47 (94) |

| Others | 1 (2) |

| Education level | |

| Unschooled | 3 (6) |

| Primary school | 10 (20) |

| Secondary school | 22 (44) |

| College/university | 15 (30) |

| Occupation | |

| Unemployed | 3 (6) |

| Retired | 43 (86) |

| Retired but still working | 2 (4) |

| Working | 2 (4) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes | 20 (40) |

| Hypertension | 35 (70) |

| Heart disease | 6 (12) |

| High cholesterol | 22 (44) |

| Parkinsonism | 1 (2) |

| Stroke | 1 (2) |

| Visual problem | 1 (2) |

| Asthma | 3 (6) |

| Thyroid | 3 (6) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4 (8) |

| Spine problem | 3 (6) |

| Gastritis | 1 (2) |

| Vertigo | 2 (4) |

| Skin problem | 1 (2) |

| Cancer | 1 (2) |

| Duration of OA | |

| Less than 1 yr | 21 (42) |

| Between 1-2 yr | 21 (42) |

| More than 3 yr | 8 (16) |

Data on self-management showed that 92% of the participants took medication and only a handful of them took alternative medicine such as ointment and herbs (10%). More than half of the participants (68%) did exercise on a daily basis. According to pain severity using VAS as a measurement tool, the median (range) for pain intensity was 7 (6.0-8.0). For the subtype of KOOS, the median (range) for KOOS pain was 14 (9.75-19.25), KOOS symptoms 11 (9-12), KOOS function 19.5 (14-30), and KOOS quality of life 9 (8-10.25) respectively. In activity of daily living, shopping appeared to be the most challenging task with 68% unable to perform, followed by food preparation (38%) and laundry (22%) respec

| n (%) | |

| Self-management | |

| Takes medication for osteoarthritis pain control | 46 (92) |

| Takes traditional supplement | 5 (10) |

| Ointment | 4 (8) |

| Herbs (Nigella Sativa sp) | 1 (2) |

| Exercise | 34 (68) |

| Exercise duration | |

| 10 min/d | 1 (2) |

| 15 min/d | 1 (2) |

| 20 min/d | 7 (14) |

| 30 min/d | 25 (40) |

| Osteoarthritis severity | |

| VAS, median (range) | 7 (6.0-8.0) |

| KOOS pain, median (range) | 14 (9.75-19.25) |

| KOOS symptoms, median (range) | 11 (9-12) |

| KOOS function, median (range) | 19.5 (14-30) |

| KOOS quality of life, median (range) | 9 (8-10.25) |

| Physical function, components of LAWTON | |

| Ability use phone | 50 (100) |

| Shopping | 16 (32) |

| Transport | 41 (82) |

| Medication | 46 (92) |

| Handling finances | 42 (84) |

| Food prep | 31 (62) |

| Laundry | 39 (78) |

| Housekeeping | 44 (88) |

| Physical frailty, components of SARC-F | |

| Strength | 15 (30) |

| Assist in walking | 10 (20) |

| Rise from chair | 12 (24) |

| Climb stair | 2 (4) |

| Falls | 40 (80) |

| Physically frail (SARC-F > 4) | 36 (72) |

Our study found that among patients who had their TKA surgery deferred during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a significant association between pain intensity and physical frailty, as measured by the odds ratio of 1.46 (95% con

| Physical function, poor IADL (Lawton < 6) | Physical frailty (SARC-F > 4) | |

| Waiting time | ||

| Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | 0.96 (0.81-1.13) | 1.09 (0.92-1.28) |

| Adjusted model 1 OR (95%CI) | 0.96 (0.81-1.13) | 1.09 (0.92-1.30) |

| Adjusted model 2 OR (95%CI) | 0.98 (0.82-1.17) | 1.07 (0.89-1.28) |

| Adjusted model 3 OR (95%CI) | 0.96 (0.81-1.13) | 1.09 (0.92-1.30) |

| Pain severity | ||

| Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | 1.14 (0.83-1.57) | 1.46 (1.04-2.05)a |

| Adjusted model 1 OR (95%CI) | 1.14 (0.82-1.57) | 1.45 (1.04-2.03)a |

| Adjusted model 2 OR (95%CI) | 1.20 (0.86-1.66) | 1.43 (1.00-2.03)a |

| Adjusted model 3 OR (95%CI) | 1.15 (0.83-1.60) | 1.45 (1.03-2.05)a |

The current study found that, in our setting, the procedure of TKA was delayed due to the pandemic, and our patients undertook self-management to cope with the conditions such as exercise and medication. Despite efforts to manage pain through self-care measures, there was a strong correlation between pain intensity and poor functional status. This suggests that a lack of proper pain management during the waiting period for surgery greatly impacted these patients’ overall function.

Our results align with those of previous studies conducted in developed countries, which have shown that delaying elective surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic can have a detrimental effect on patients’ quality of life, overall health, and independence[12-14]. Specifically, our study observed that the functional status of patients who were waiting for TKA to be rescheduled was poor. This could be due to chronic conditions of OA related symptoms which can greatly affect their daily activities[15]. However, the length of TKR waiting time does not reflect pain intensity, which is in line with previous systematic review[16]. The severity of OA required to be referred to TKR was argued due to underuse of nonoperative treatments beforehand. This might influence the pain intensity reports arose from varied disease pro

Despite the widespread postponing of elective surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic, a limited number of studies suggest that such surgeries may be safely carried out with appropriate precautions in place. For example, a retrospective study found that elective surgeries could be resumed with additional precautions taken[18]. Furthermore, some research has indicated that elective surgeries can proceed as scheduled if the patient tests if the patient priorly tested positive for COVID-19, with a certain period of time having passed, such as seven weeks or more. In the United Kingdom specifically, one study found that the 30-d mortality rate after elective surgery was lower among patients who had surgery at seven weeks or more post-positive COVID-19 test results compared to those who underwent surgery within six weeks of a positive test result, with a 3.5 to 4 times higher risk of death[19]. Another study supports that waiting seven weeks or more after a COVID-19 infection to undergo surgery may be optimal[20]. Despite the spike in COVID-19 cases, older patients with severe OA may still opt to undergo surgery depending on their level of pain[21].

Exercise, by improving neuromuscular control, joint range of motion and strengthening muscle, helps in managing pain, improving functional status and quality of life of people with knee OA, especially elderlies with multitube of com

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, the sample size of this study was relatively small, as we employed a purposive sampling method and the average number of TKA cases at the institution was only 100 per year. While this may not represent the entire population of Malaysia, the study institution caters to almost 500000 residents living in the surrounding areas of Selangor, thus the results can be considered representative of this population. Secondly, due to limited data access and participants’ availability, the amount of data collected was restricted. Addi

This study did not find significant association between waiting time for TKA surgery and poor physical function or frailty, suggesting the postponement was not the main factor that bore negative effect on self-management, pain, and physical function in older patients aged 50 and above. Nevertheless, the significant association between pain and physical frailty highlights the importance of closely monitoring these patients for OA pain management during the waiting period to prevent declines in physical function and frailty, and to maintain their independence. Additionally, this research may aid healthcare providers in creating emergency protocols for future pandemics that may cause further postponements of elective surgeries. Such protocols should prioritize older patients for TKA procedures and emphasize thorough moni

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) served as the last resort for individuals with severe knee osteoarthritis (OA), reducing burdens from pain and symptoms which interfere with activities of daily living. Upon happening of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), health care setting was overloaded with critical medical condition patients, rendering scheduled surgeries postponed. The consequences of delayed TKA remain unknown. As the capital of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur has hospitals that served during COVID-19, hence is suitable to be appointed as the location for sample recruitment.

OA is a high prevalence degenerative joint disease, in Malaysia, patients with late-stage OA are usually appointed for TKA as last resort of treatment. Due to COVID-19, their TKA had to be rescheduled, the impact this adjustment should be aware as movement restriction during the pandemic left the patients with self-management to deal with knee pain and symptoms, their physical function and quality of life may worsen if misguided practice was done. The significance of understanding how length of TKR waiting time affects pain, physical frailty and overall health may provide input for physician to plan future guidelines in TKR.

The research objective of this study is to investigate the effects of COVID-19 pandemic on self-management, pain, and physical function in older adults awaiting TKA in Malaysia. By examining the length of TKR waiting time and the self-management, pain, and physical function of older adults with knee OA, we may provide input for healthcare providers in creating emergency protocols for future pandemics that may cause further postponements of elective surgeries.

Using information from a TKA registry, this study employed a cross-sectional survey approach to assess the impact of surgical postponement on patient health status and self-management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data were anonymously gathered from the Department of Orthopaedic at the Hospital Canselor Tuanku Mukhriz (HCTM) in Malaysia on patients who were in the waiting period for elective TKA between January 2021 and May 2022. The HCTM caters approximately 500000 Malaysian citizens who lived in the areas of Cheras, Ampang, Hulu Langat, Semenyih and Bangi. Patients who had undergone TKR surgery or had an appointment for a revision were not included. Data for this study was gathered on-site. The study was divided into two stages: The first stage included data extraction from the TKA registry, and the second stage comprised performing a survey on patients’ health state and self-management. The survey questionnaires were disseminated after contacting them and obtaining their agreement.

Based on sample size of 50 older adults, the study found a significant association between pain intensity and physical frailty even after adjustment for age and self-management practices, however, not between length of TKR waiting time and poor physical function or frailty. The chronic comorbidities may be one of the factors. Over half of the participants exercise on daily basis, and yet 72% of the participants were found to have physical frailty. This suggests exercise alone is not enough, psychological intervention, patient education, and monitoring, for example, remote telecommunication consultation may aid in the management.

This study did not find significant association between waiting time for TKA surgery and poor physical function or frailty, suggesting the postponement was not the main factor that bore negative effect on self-management, pain, and physical function in emphasized that older patients aged 50 and above were disproportionately impacted by the postponement of TKA procedures due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, the significant association between pain and physical frailty. It highlights the importance of closely monitoring these patients for OA pain management treatment during the waiting period to prevent declines in physical function and frailty, and to maintain their independence.

Future research may focus on creating emergency protocols for future pandemics that may cause further postponements of elective surgeries. The management should include and investigate the synergy effect of psychological intervention, patient education and monitoring with exercise.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Malaysia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Belluzzi E, Italy; Rezus E, Romania S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Meo SA, Al-Khlaiwi T, Usmani AM, Meo AS, Klonoff DC, Hoang TD. Biological and epidemiological trends in the prevalence and mortality due to outbreaks of novel coronavirus COVID-19. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2020;32:2495-2499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Elengoe A. COVID-19 Outbreak in Malaysia. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2020;11:93-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sharma L. Osteoarthritis of the Knee. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:51-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 580] [Article Influence: 145.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | O'Neill TW, Felson DT. Mechanisms of Osteoarthritis (OA) Pain. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2018;16:611-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cui A, Li H, Wang D, Zhong J, Chen Y, Lu H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29-30:100587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 709] [Article Influence: 141.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kienzle A, Biedermann L, Babeyko E, Kirschbaum S, Duda G, Perka C, Gwinner C. Public Interest in Knee Pain and Knee Replacement during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in Western Europe. J Clin Med. 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Barnes CL, Zhang X, Stronach BM, Haas DA. The Initial Impact of COVID-19 on Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2021;36:S56-S61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zulkifli MM, Kadir AA, Elias A, Bea KC, Sadagatullah AN. Psychometric Properties of the Malay Language Version of Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) Questionnaire among Knee Osteoarthritis Patients: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Malays Orthop J. 2017;11:7-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Roos EM, Toksvig-Larsen S. Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) - validation and comparison to the WOMAC in total knee replacement. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 625] [Cited by in RCA: 730] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Malmstrom TK, Morley JE. SARC-F: a simple questionnaire to rapidly diagnose sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:531-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 430] [Cited by in RCA: 688] [Article Influence: 57.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Graf C. The Lawton instrumental activities of daily living scale. Am J Nurs. 2008;108:52-62; quiz 62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 483] [Article Influence: 28.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pietrzak JRT, Maharaj Z, Erasmus M, Sikhauli N, Cakic JN, Mokete L. Pain and function deteriorate in patients awaiting total joint arthroplasty that has been postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. World J Orthop. 2021;12:152-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sommer JL, Jacobsohn E, El-Gabalawy R. Impacts of elective surgical cancellations and postponements in Canada. Can J Anaesth. 2021;68:315-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kort NP, Zagra L, Barrena EG, Tandogan RN, Thaler M, Berstock JR, Karachalios T. Resuming hip and knee arthroplasty after COVID-19: ethical implications for wellbeing, safety and the economy. Hip Int. 2020;30:492-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Brown TS, Bedard NA, Rojas EO, Anthony CA, Schwarzkopf R, Stambough JB, Nandi S, Prieto H, Parvizi J, Bini SA, Higuera CA, Piuzzi NS, Blankstein M, Wellman SS, Dietz MJ, Jennings JM, Dasa V; AAHKS Research Committee. The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Patients in the United States: A Multicenter Update to the Previous Survey. Arthroplast Today. 2021;7:268-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Patten RK, Tacey A, Bourke M, Smith C, Pascoe M, Vogrin S, Parker A, McKenna MJ, Tran P, De Gori M, Said CM, Apostolopoulos V, Lane R, Woessner MN, Levinger I. The impact of waiting time for orthopaedic consultation on pain levels in individuals with osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022;30:1561-1574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lebedeva Y, Churchill L, Marsh J, MacDonald SJ, Giffin JR, Bryant D. Wait times, resource use and health-related quality of life across the continuum of care for patients referred for total knee replacement surgery. Can J Surg. 2021;64:E253-E264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Meena OP, Kalra P, Shukla A, Naik AK, Iyengar KP, Jain VK. Is performing joint arthroplasty surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic safe?: A retrospective, cohort analysis from a tertiary centre in NCR, Delhi, India. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2021;21:101512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Prvu Bettger J, Thoumi A, Marquevich V, De Groote W, Rizzo Battistella L, Imamura M, Delgado Ramos V, Wang N, Dreinhoefer KE, Mangar A, Ghandi DBC, Ng YS, Lee KH, Tan Wei Ming J, Pua YH, Inzitari M, Mmbaga BT, Shayo MJ, Brown DA, Carvalho M, Oh-Park M, Stein J. COVID-19: maintaining essential rehabilitation services across the care continuum. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | COVIDSurg Collaborative; GlobalSurg Collaborative. Timing of surgery following SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2021;76:748-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 403] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 91.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gómez-Barrena E, Rubio-Saez I, Padilla-Eguiluz NG, Hernandez-Esteban P. Both younger and elderly patients in pain are willing to undergo knee replacement despite the COVID-19 pandemic: a study on surgical waiting lists. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2022;30:2723-2730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Goh SL, Persson MSM, Stocks J, Hou Y, Lin J, Hall MC, Doherty M, Zhang W. Efficacy and potential determinants of exercise therapy in knee and hip osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2019;62:356-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen H, Zheng X, Huang H, Liu C, Wan Q, Shang S. The effects of a home-based exercise intervention on elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Karasavvidis T, Hirschmann MT, Kort NP, Terzidis I, Totlis T. Home-based management of knee osteoarthritis during COVID-19 pandemic: literature review and evidence-based recommendations. J Exp Orthop. 2020;7:52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jain VK, Iyengar KP, Upadhyaya GK, Vaishya R. Nonoperative Strategies to Manage Pain in Osteoarthritis during COVID-19 Pandemic. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2020;14. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Anthony CA, Rojas E, Glass N, Keffala V, Noiseux N, Elkins J, Brown TS, Bedard NA. A Psycholgical Intervention Delivered by Automated Mobile Phone Messaging Stabilized Hip and Knee Function During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Arthroplasty. 2022;37:431-437.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |