Published online Oct 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i29.6995

Peer-review started: July 8, 2023

First decision: August 30, 2023

Revised: September 11, 2023

Accepted: September 23, 2023

Article in press: September 25, 2023

Published online: October 16, 2023

Processing time: 96 Days and 21.4 Hours

Sessile serrated lesions (SSLs) are often missed on colonoscopy, and studies have shown this to be an essential cause of interstitial colorectal cancer. The SSLs with dysplasia (SSL-D+), in particular, have a faster rate of carcinogenesis than conventional tubular adenomas. Therefore, there is a clinical need for some endoscopic features with independent diagnostic value for SSL-D+s to assist endoscopists in making immediate diagnoses, thus improving the quality of endoscopic examina

To compare the characteristics of SSLs, including those with and without dyspla

From January 2017 to February 2023, cases of colorectal SSLs confirmed by colo

A total of 228 patients with 253 lesions were collected as a result. There were 225 cases of colorectal SSL-D-s and 28 cases of SSL-D+s. Compared to the colorectal SSL-D-, the SSL-D+ was more common in the right colon (P = 0.027) with complex patterns of depression, nodule, and elevation based on cloud-like surfaces (P = 0.003), reddish (P < 0.001), microvascular varicose (P < 0.001), and mixed type (Pit II, II-O, IIIL, IV) of crypt opening based on Pit II-O (P < 0.001). Multifactorial logistic regression analysis indicated that lesions had a reddish color [odds ratio (OR) = 18.705, 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.684-94.974], microvascular varicose (OR = 6.768, 95%CI: 1.717-26.677), and mixed pattern of crypt opening (OR = 20.704, 95%CI: 2.955-145.086) as the independent predictors for SSL-D+s.

The endoscopic feature that has independent diagnostic value for SSL-D+ is a reddish color, microvascular varicose, and mixed pattern of crypt openings.

Core Tip: The colonoscopic features of colorectal sessile serrated lesions (SSLs) make them easy to be overlooked in screening, which is an essential reason for the emergence of interstage colorectal cancer. With the advancement of endoscopic techniques and refinement of the serrated carcinoma pathway, the SSL is gradually being recognized by endoscopists, especially for SSL with dysplasia (SSL-D+), which requires extra attention. In this study, we analyzed the endoscopic features of SSLs with and without dysplasia, and found characteristics that could independently diagnose SSL-D+ by multifactorial analysis, which is informative for immediate diagnosis by endoscopists.

- Citation: Wang RG, Ren YT, Jiang X, Wei L, Zhang XF, Liu H, Jiang B. Usefulness of analyzing endoscopic features in identifying the colorectal serrated sessile lesions with and without dysplasia. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(29): 6995-7003

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i29/6995.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i29.6995

At the end of the 20th century, a group of lesions with characteristics similar to those of hyperplastic polyposis identified by Torlakovic and Snover[1], which showed a broad-based growth pattern endoscopically but lacked heterogeneous hyperplasia and were dubbed “sessile serrated adenoma (SSA)”. According to the 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System, the SSA/polyp (SSA/P) is a subtype of the serrated polyp. However, the 5th edition of the WHO Classification of Gastrointestinal Tumors 2019 renamed SSA/Ps to sessile serrated lesions (SSLs) due to the progression of the serrated pathway of colorectal carcinoma[2]. SSLs have poorly defined bor

The unique endoscopic features of colorectal SSLs make it a significant risk factor for the development of interstitial colorectal cancer. Notably, with the continuous advancement and development of endoscopy techniques, equipment, and accessories, potent tools exist for the precise observation and prompt diagnosis of colorectal SSLs. Based on the pathologic diagnostic criteria, SSLs were categorized as SSLs with and without dysplasia (SSL-D+ and SSL-D-). In addition, there have been reports of SSL-D+s transforming into submucosal invasive carcinomas within a short period[5-7], that is to say, once a diagnosis of SSL-D+ has been made, the progression to serrated adenocarcinoma can be rapid.

From January 2017 to February 2023, colorectal SSLs confirmed by histopathology during colonoscopy at the Gastro

The endoscopic systems were colonoscopy series EC-590WM/EC-790ZP (Fuji Film, Japanese) and CF-H290I/CF-HQ290I (Olympus, Japanese), which utilized white light, blue laser imaging (BLI) and narrow band imaging (NBI) to observe and store images of lesions. In addition, an endoscopic procedure was performed using ERBE 200D high-frequency electro

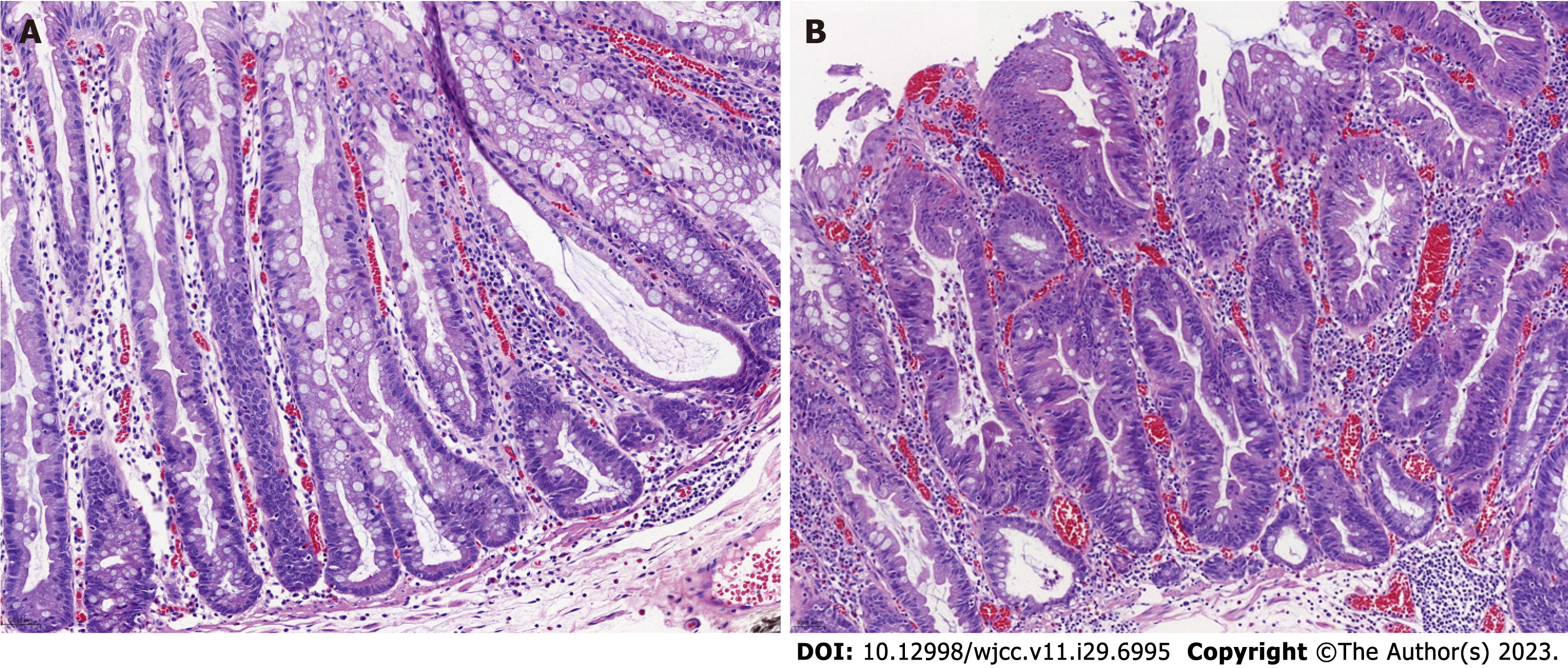

Suspected SSLs were analyzed by colonoscopy in white light and BLI/NBI mode with the following characteristics: Site (left/right colon), size (</≥ 10 mm), surface mucus cap (no/yes, Figure 1A), surface morphology (cloud-like/mixed-like: Depressed, nodular, elevated), lesion color (pale/reddish) (Figures 1B and C), crypt black spots (no/yes, Figure 1D), and microvascular varicose (no/yes, Figure 1E), crypt opening morphology (Pit II-O type/mixed type base on Pit II-O, Figure 1F). Three seasoned endoscopists (with more than ten years of gastrointestinal endoscopy operation) examined all endoscopic figures. The decision was accepted if there was unanimity among the three endoscopists; otherwise, a vote was held.

After colorectal SSLs were resected, the lesion surface was rinsed of mucus and impurities to expose the lesion mor

Data management and statistical analysis were performed using SPSS 20. Case counts were expressed as cases (in %). The χ2 test and Fisher’s precision probability test were used to compare univariate data. Variables with P < 0.1 were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. P < 0.05 indicates a statistically significant difference.

This study collected 228 patients with histopathologically confirmed SSL, of which 119 (52.19%) were male, and 109 (47.81%) were female. The mean age of the SSL-D- group was 57.25 ± 12.02 years, while the SSL-D+ group was 60.00 ± 11.27 years. In the enrolled cases, a total of 253 lesions were identified (two lesions in 18 patients, three lesions in two patients, and four lesions in one patient), with 225 (88.93%) cases being colorectal SSL-D-s and 28 (11.07%) cases being colorectal SSL-D+s. Three patients were detected with one SSL-D- and one SSL-D+. Regarding gender and age, there were no statistically significant differences between the SSL-D- and SSL-D+ groups (P > 0.05).

Endoscopic features of colorectal SSL-D-s: 146 cases located in the right colon, 186 with diameter ≥ 10 mm, 48 with complex morphology (e.g., depressions, nodules, and elevations based on cloud-like), 119 covered with mucus cap, 9 with a reddish color, 130 with black dots visible on the surface of lesions in BLI/NBI pattern and 15 with visible submucosal microvascular varicose under BLI/NBI pattern. As for crypt opening, the pattern mixed type (II, II-O, IIIL, IV) based on Pit II-O type had 2 cases.

Endoscopic features of colorectal SSL-D+s: 24 cases located in the right colon, 27 with diameter ≥ 10 mm, 13 with complex morphology (e.g., depressions, nodules, and elevations based on cloud-like), 19 covered with mucus cap, 18 with a reddish color, 16 with black dots visible on the surface of lesions in BLI/NBI pattern, and 15 with visible submucosal microvascular varicose under BLI/NBI pattern. As for crypt opening, the pattern mixed type (II, II-O, IIIL, IV) based on Pit II-O type had 15 cases.

Compared to the SSL-D-, the SSL-D+ occurred more frequently in the right colon, and its surface displayed a complex morphology of depressions, nodules, and elevations on a cloud-like surface with a reddish hue. The crypt opening was predominantly of mixed type (II, II-O, IIIL, IV), and the lesion mucosa displayed microvascular varicose. The above endoscopic features of colorectal SSL-D+s were statistically distinct from those of SSL-D-s (P < 0.05). In contrast, the differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05) for the lesion diameter exceeding 10 mm, with or without a mucosal cap, and the presence or absence of black spots in the BLI/NBI pattern. The general and endoscopic features data as shown in Table 1.

| Factors | SSL-D- group (n = 217) | SSL-D+ group (n = 22) | χ2 | P value |

| Gender | 0.001 | 0.981 | ||

| Male | 120 | 15 | ||

| Female | 105 | 13 | ||

| Age | 57.25 ± 12.02 | 60.00 ± 11.27 | 1.1482 | 0.252 |

| Location | 4.899 | 0.027 | ||

| Left colon | 79 | 4 | ||

| Right colon | 146 | 24 | ||

| Size | 0.0941 | |||

| < 10 mm | 39 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 10 mm | 186 | 27 | ||

| Surface shape | 8.571 | 0.003 | ||

| Cloud-like | 177 | 15 | ||

| Mixed-like | 48 | 13 | ||

| Mucus cap | 2.250 | 0.134 | ||

| No | 106 | 9 | ||

| Yes | 119 | 19 | ||

| Color | 99.6.3 | < 0.0011 | ||

| Pale | 217 | 10 | ||

| Reddish | 8 | 18 | ||

| Black spots | 0.004 | 0.949 | ||

| No | 95 | 12 | ||

| Yes | 130 | 16 | ||

| Microvascular varicose | 57.791 | < 0.0011 | ||

| No | 212 | 13 | ||

| Yes | 13 | 15 | ||

| Crypt opening | < 0.0011 | |||

| Type II-O | 223 | 13 | ||

| Mixed type | 2 | 15 |

The right colon, mixed surface morphology, reddish color, mixed crypt opening pattern, and intramucosal microvascular varicose are potential factors for the independent diagnosis of SSL-D+s, according to the univariate analysis. Multifactorial logistic regression analysis of the above factors revealed that the location features of the right colon (P = 0.172) and complex pattern of surface shape (e.g., depressions, nodules, and elevations on a cloud-like basis, P = 0.817) were not independent diagnostic factors for SSL-D+s. Meanwhile, lesion of reddish color [odds ratio (OR) = 18.705, 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.684-94.974], the finding of microvascular varicose within the mucosa (OR = 6.768, 95%CI: 1.717-26.677), and crypt opening showing the mixed type (II, II-O, IIIL, IV) based on Pit II-O (OR = 20.704, 95%CI: 2.955-145.086) were independent diagnostic factors for SSL-D+s (Table 2).

| Factors | Wals | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Location (left/right colon) | 1.865 | 0.172 | 3.390 | 0.588-19.546 |

| Size (< 10 mm/≥ 10 mm) | 0.028 | 0.867 | 1.206 | 0.135-10.782 |

| Surface shape (cloud-like/mixed-like) | 0.053 | 0.817 | 1.204 | 0.250-5.803 |

| Color (pale/reddish) | 12.482 | < 0.001 | 18.705 | 3.684-94.974 |

| Varicose microvascular (No/Yes) | 7.467 | 0.006 | 6.768 | 1.717-26.677 |

| Crypt opening (II-O/mixed) | 9.306 | 0.002 | 20.704 | 2.955-145.086 |

In this study, a univariate analysis was used to find endoscopic features of potential value in the diagnosis of colorectal SSL-D+s, upon which a multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to obtain endoscopic features of inde

In a population-based case-control study conducted in Denmark, the risk of colorectal cancer was significantly higher in cases of colorectal SSLs than in cases of conventional adenomas[9]. Studies suggest that it takes 7-15 years for colorectal SSL-D-s to progress to SSL-D+s, and after 5-7 years of follow-up, 3.03%-12.5% of SSL patients develop colorectal cancer[10]. SSL-D+s proliferation progresses to colorectal cancer much earlier, with cases reported previously indicating that SSL-D+s progress to invasive submucosal carcinoma within 1-2 years[11-13]. This finding suggests that ignoring SSLs is likely to increase the risk of colorectal cancer in the intermediate stages. Therefore, early identification and treatment of SSLs (especially SSL-D+s) is crucial. Meanwhile, among colorectal SSLs, SSL-D+s are uncommon, and only 28 cases of SSL-D+s are identified in this study, representing 11.07% (28/253), similar to the structure of previous studies[14].

The size of colorectal SSLs > 10 mm positively correlates with SSL-D+s’ emergence, but in a study that included 48 cases of SSL-D+s, over one-third of cases had a diameter ≤ 10 mm[15,16]. Consistent with the present study’s findings, the size of colorectal SSLs is not an independent diagnostic factor for SSL-D+s. Mucus cap has been confirmed as the primary distinction between colorectal SSLs and hyperplastic polyps (HPs); however, it has no diagnostic value for distinguishing the SSL-D- and SSL-D+, which is consistent with the results of this study[16,17]. With image enhancement endoscopy (e.g., BLI/NBI), the crypt openings of colorectal SSLs frequently exhibit small brownish-black dots with an enlarged crypt. Considered a critical histological distinction between SSLs and HPs, but this phenomenon has no diagnostic value for SSL-D-s and SSL-D+s[17,18].

In this study, the location of the lesion in the right colon was confirmed as a potential diagnostic factor for the SSL-D+ (P = 0.027), similar to previous studies[19,20]. However, in a multifactorial regression analysis screening for independent diagnostic factors of SSL-D+s, the location was not found to be an independent factor (P = 0.172). This is likely because previous studies have focused on the sensitivity and specificity of the single factor of right hemicolectomy in predicting SSL-D+s without excluding the possibility that other endoscopic features interfere with its independent diagnostic value[4,15,21,22].

In addition, endoscopic examination of the colorectal SSL-D+ reveals the following predominant morphology: (Semi)pedunculated, double elevations, central depressions, and reddishness[16,22]. In the univariate analysis of this study, SSL-D+s endoscopically demonstrated predominantly complex morphology of depressions, nodules, and eleva

In this study, the colorectal SSL-D+ is more likely to exhibit a reddish color under conventional white light endoscopy, and this is an independent diagnostic factor for SSL-D+ according to multifactorial regression analysis (OR = 18.705, 95%CI: 3.684-94.974), similar to previous findings[15,16]. It is not difficult to understand that when SSLs with dysplasia or cancer are diagnosed, there is a corresponding increase in the demand for blood supply.

It has been established that intramucosal microvascular varicose differs from the superficial mucosal glands’ surrounding microvasculature. Therefore, at sites of colorectal SSL-D+s, there may be dilated and irregular capillaries, and in serrated adenocarcinomas with submucosal infiltration, their surface microvascularity or structure disappears[19,21,23]. In other words, this endoscopic feature is important for suggesting an immediate diagnosis. As this study found, the rate of microvascular varicose is higher in the SSL-D+ group than in the SSL-D- group and the differences are statistically significant (P = 0.006).

The use of magnified endoscopy to observe SSLs revealed that the appearance of type III, IV, and V crypt open mor

The following deficiencies persist in this study. First, there is a retrospective, single-center clinical study, and there may be some bias in the endoscopists’ subjective evaluations. Second, all the cases included in this study were precancerous, which may lead to bias in the study results. The reason is that if cases of SSL-D-s, SSL-D+s, and SSL cancerous lesions are included, it would be realized to analyze the consecutive complete endoscopic features of such lesions in different stages, and that design might be more convincing. Third, the cases enrolled in the study were discovered by different endo

Observation allows endoscopic features of colorectal SSLs to be effectively identified. SSL-D+s should be strongly sus

Missing diagnosis of sessile serrated lesions (SSLs), especially SSLs with dysplasia (SSL-D+s), is an important cause of interstitial colorectal cancer, and in this study, we hoped to find endoscopic features that have independent diagnostic value for SSL-D+s.

Previous studies on the endoscopic features of SSLs have focused on their differentiation from hyperplastic polyps and tubular adenomas, and comparisons of the endoscopic features of SSLs without dysplasia (SSL-D-s) and SSL-D+s have remained at the level of prediction of the sensitivity and specificity of individual endoscopic features. There have been several reports in the literature that SSL-D+s have a risk of faster progression to adenocarcinoma compared to SSL-D-s and conventional tubular adenomas. Therefore, it is important to look for endoscopic features that have independent pre

This study looks for endoscopic features that have independent diagnostic value for colorectal SSL-D+s. These features may help endoscopists to make immediate diagnoses during colonoscopy.

In this study, endoscopic features potentially predictive of SSLs were first analyzed by univariate analysis, and then multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to obtain endoscopic features with independent diagnostic value for predicting SSL-D+s and the diagnostic validity of these endoscopic features.

In univariate analysis, location, size, surface shape, color, microvascular varices, and crypt opening pattern of colorectal SSLs had value in predicting SSL-D+s. In multifactorial regression analysis, color, microvascular varices and crypt open

Reddish color, microvascular varicose, and mixed pattern of crypt openings are independent diagnostic features for colorectal SSL-D+s.

This finding is expected to improve the immediate diagnostic accuracy of endoscopists in SSL-D+s in order to inform them to use appropriate endoscopic treatment modalities.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kawabata H, Japan S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Torlakovic E, Snover DC. Serrated adenomatous polyposis in humans. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:748-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F, Cree IA; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2554] [Cited by in RCA: 2441] [Article Influence: 488.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Chang LC, Tu CH, Lin BR, Shun CT, Hsu WF, Liang JT, Wang HP, Wu MS, Chiu HM. Adjunctive use of chromoendoscopy may improve the diagnostic performance of narrow-band imaging for small sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:466-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tanaka Y, Yamano HO, Yamamoto E, Matushita HO, Aoki H, Yoshikawa K, Takagi R, Harada E, Nakaoka M, Yoshida Y, Eizuka M, Sugai T, Suzuki H, Nakase H. Endoscopic and molecular characterization of colorectal sessile serrated adenoma/polyps with cytologic dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:1131-1138.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Oono Y, Fu K, Nakamura H, Iriguchi Y, Yamamura A, Tomino Y, Oda J, Mizutani M, Takayanagi S, Kishi D, Shinohara T, Yamada K, Matumoto J, Imamura K. Progression of a sessile serrated adenoma to an early invasive cancer within 8 months. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:906-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | East JE, Vieth M, Rex DK. Serrated lesions in colorectal cancer screening: detection, resection, pathology and surveillance. Gut. 2015;64:991-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bateman AC. The spectrum of serrated colorectal lesions-new entities and unanswered questions. Histopathology. 2021;78:780-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li J, Teng XD, Lai MD. [Colorectal non-invasive epithelial lesions: an update on the pathology of colorectal serrated lesions and polyps]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49:1339-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Erichsen R, Baron JA, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Snover DC, Torlakovic EE, Pedersen L, Frøslev T, Vyberg M, Hamilton SR, Sørensen HT. Increased Risk of Colorectal Cancer Development Among Patients With Serrated Polyps. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:895-902.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | IJspeert JE, Vermeulen L, Meijer GA, Dekker E. Serrated neoplasia-role in colorectal carcinogenesis and clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:401-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Amemori S, Yamano HO, Tanaka Y, Yoshikawa K, Matsushita HO, Takagi R, Harada E, Yoshida Y, Tsuda K, Kato B, Tamura E, Eizuka M, Sugai T, Adachi Y, Yamamoto E, Suzuki H, Nakase H. Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp showed rapid malignant transformation in the final 13 months. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:979-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Omori K, Yoshida K, Tamiya S, Daa T, Kan M. Endoscopic Observation of the Growth Process of a Right-Side Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyp with Cytological Dysplasia to an Invasive Submucosal Adenocarcinoma. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2016;2016:6576351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kinoshita S, Nishizawa T, Uraoka T. Progression to invasive cancer from sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lash RH, Genta RM, Schuler CM. Sessile serrated adenomas: prevalence of dysplasia and carcinoma in 2139 patients. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:681-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Murakami T, Sakamoto N, Ritsuno H, Shibuya T, Osada T, Mitomi H, Yao T, Watanabe S. Distinct endoscopic characteristics of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with and without dysplasia/carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:590-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Murakami T, Sakamoto N, Nagahara A. Endoscopic diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with and without dysplasia/carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3250-3259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 17. | Hazewinkel Y, López-Cerón M, East JE, Rastogi A, Pellisé M, Nakajima T, van Eeden S, Tytgat KM, Fockens P, Dekker E. Endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas: validation by international experts using high-resolution white-light endoscopy and narrow-band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:916-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yamashina T, Takeuchi Y, Uedo N, Aoi K, Matsuura N, Nagai K, Matsui F, Ito T, Fujii M, Yamamoto S, Hanaoka N, Higashino K, Ishihara R, Tomita Y, Iishi H. Diagnostic features of sessile serrated adenoma/polyps on magnifying narrow band imaging: a prospective study of diagnostic accuracy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:117-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Murakami T, Sakamoto N, Fukushima H, Shibuya T, Yao T, Nagahara A. Usefulness of the Japan narrow-band imaging expert team classification system for the diagnosis of sessile serrated lesion with dysplasia/carcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:4528-4538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Murakami T, Sakamoto N, Nagahara A. Clinicopathological features, diagnosis, and treatment of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia/carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:1685-1695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang Y, Ren YB, Yang XS, Huang YH, Zhang L, Li X, Bai P, Wang L, Fan X, Ding YM, Li HL, Lin XC. [Comparison of endoscopic features between colorectal sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with or without cytologic dysplasia and hyperplastic polyp]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2019;99:2214-2220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sano W, Fujimori T, Ichikawa K, Sunakawa H, Utsumi T, Iwatate M, Hasuike N, Hattori S, Kosaka H, Sano Y. Clinical and endoscopic evaluations of sessile serrated adenoma/polyps with cytological dysplasia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:1454-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Saito S, Tajiri H, Ikegami M. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum: Endoscopic features including image enhanced endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:860-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |