Published online Oct 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i28.6889

Peer-review started: June 19, 2023

First decision: August 16, 2023

Revised: August 30, 2023

Accepted: September 6, 2023

Article in press: September 6, 2023

Published online: October 6, 2023

Processing time: 98 Days and 5.5 Hours

Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (PC-ALCL) differs from systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (sALCL) in cell biological behavior, clinical features, treatment, and outcome. PC-ALCL has been reported to rarely transition into sALCL, but the underlying mechanism is not clear. Here we report such a case with certain characteristics that shed light on this.

Herein, we report a 43-year-old male with symptoms of a skin nodule and histologically confirmed PC-ALCL with high expression of Ki-67. After three months of observation, two skin nodules re-appeared with muscle layer involvement and was histologically confirmed as sALCL. Seventeen months after receiving six cycles of CHOP regimen, the patient had pain in the chest and back, cough, shortness of breath, and night sweats. This was confirmed as relapse of sALCL by immunohistochemistry and several organs, such as the lung were involved as shown by positron emission tomography/computed tomography. After four cycles of DICE plus chidamide regimens followed by auto-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT), complete remission (CR) duration was achieved for twelve months while the patient was on maintenance with chidamide (20 mg) pills.

This case had significantly high expression of Ki-67 when diagnosed as PC-ALCL initially and then transitioned into sALCL, which is rare. Auto-ASCT combined with demethylation drugs effectively maintained CR and prolonged progression free survival.

Core Tip: Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (PC-ALCL) is a primary cutaneous lymphoma and differs from systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (sALCL), which is a peripheral T cell lymphoma. There is no direct connection between them. This is the first report of the medical management, including auto-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT) of a 43-year-old male patient who transitioned from the cutaneous to the systemic form of ALCL in Asia, and the second to be reported in world (the first being a Bulgarian treated with Brentuximab vedontin). We found high expression of Ki-67 in this case, for the first time, which may have played a role in the transition. This is also the first instance of application of auto-ASCT followed by maintenance with oral chidamide. In the future, an increasing number of patients will probably receive this therapy, and therein lies the significance of this case report.

- Citation: Mu HX, Tang XQ. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma with over-expressed Ki-67 transitioning into systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(28): 6889-6894

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i28/6889.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i28.6889

Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (PC-ALCL) accounts for about 8% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas[1]. In the 2022 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms, PC-ALCL is categorized under primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoid proliferations and lymphomas[2]. PC-ALCL exhibits an indolent clinical course with a highly favorable outcome; 5-year survival ranges between 85% and 100%, although cutaneous relapses are common[3,4]. The median age at diagnosis is six decades for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) negative PC-ALCL. Clinical features typically include solitary, grouped skin lesions and uncommonly localized nodules or tumors. Extracutaneous disease occurs in about 10% of cases, usually involving regional lymph nodes[3].

Peripheral T cell lymphoma (PTCL), an aggressive disease that belongs to a heterogeneous group of mature T-cell lymphomas, develops rapidly and has a poor prognosis. ALK-negative ALCL, as one kind of PTCL, has been acknowledged as a heterogeneous entity. Only one case of transition from PC-ALCL to systemic ALCL (sALCL) has been reported so far in the literature[5]. However, little is known about the underlying mechanism. Here, we report a 43-year-old male patient diagnosed as PC-ALCL who then transitioned into ALK-negative sALCL. We analyzed molecular markers, including Ki-67 and DUSP22 rearrangement to provide additional information.

Awareness of skin nodules for 4 years; thoracalgia and shortness of breath for 2 years.

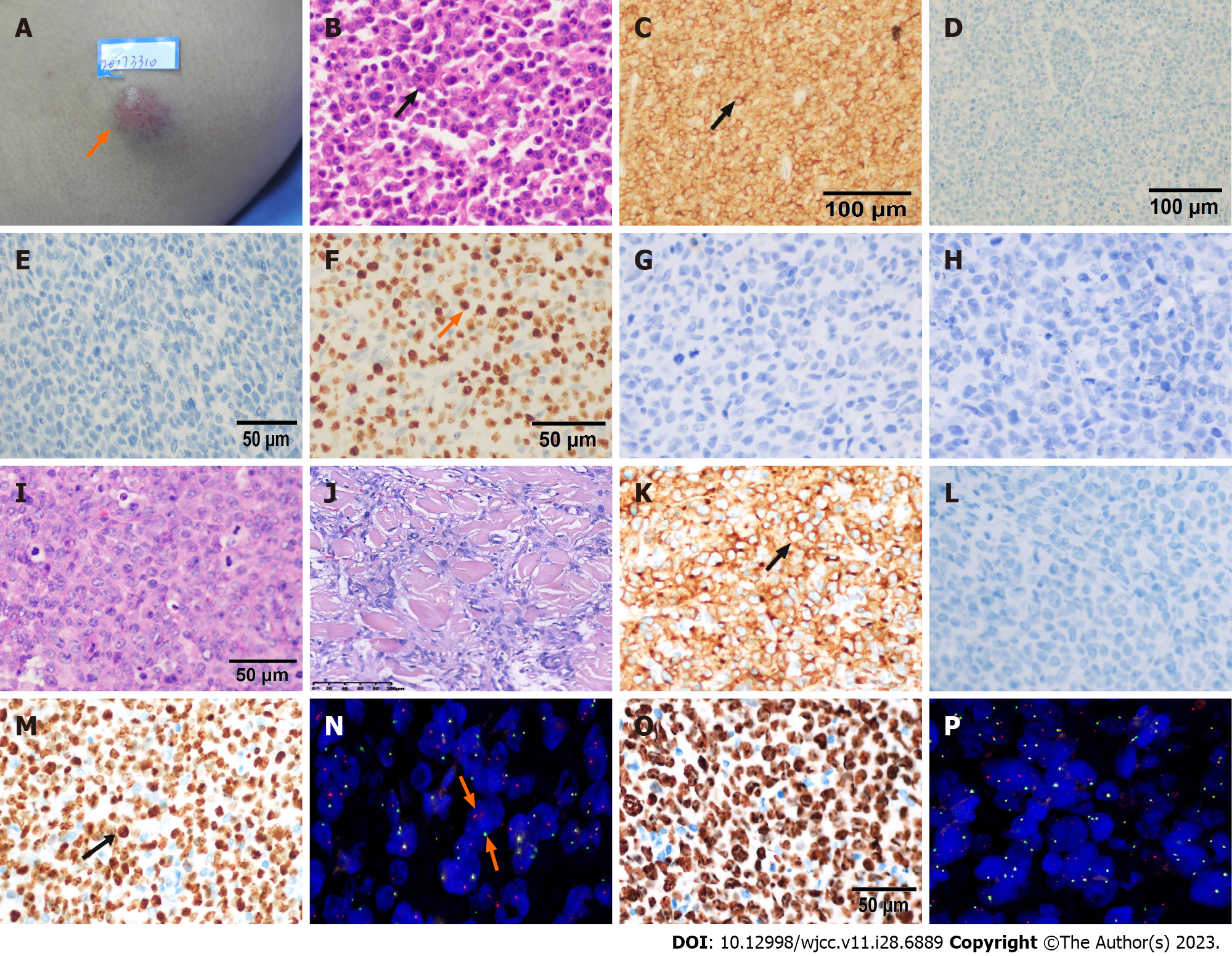

A 43-year-old male presented with a left sided 2 cm × 2 cm, hard arm swelling without itching or pain (Figure 1A). There were no other skin lesions or lymphadenopathy or significant organomegaly. The local lesion was excised. On histopathology, a diagnosis of ALK-negative PC-ALCL was made (Figure 1B–H). This patient then underwent observation for recurrence.

Three months later, two subcutaneous hard nodules recurred at the same spot on the left arm. They were 1 cm × 2 cm and 0.5 cm × 1 cm in dimensions. The skin lesions were confirmed as relapsed lymphoma with muscle layer infiltration on histopathology (Figure 1I–M). We diagnosed this new disease entity as systemic ALK-negative ALCL since the muscle was involved, although bone marrow biopsy and aspirate and whole-body CT scan were normal. The patient underwent treatment with six cycles of multiagent chemotherapy, CHOP (cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2, theprubicin 30 mg/m2, vindesine 3 mg/m2, prednisone 100 mg). He refused treatment with brentuximab and auto-ASCT, and instead chose follow-up.

Two years later, this patient suffered from chest pain, shortness of breath, cough, and night sweats.

The patient reported no other medical history, such as hypertension and diabetes.

The patient denied any personal and family history of illness.

The patient’s height was 189 cm and his weight was 103 kg. He was clear-headed and energetic, and had no swelling of superficial lymph nodes. He had a 1 cm × 1 cm subcutaneous nodule on his back with clear border. He had tenderness in the mid-sternum and bilateral anterior chest wall, clear breath sounds in both lungs, uniform cardiac rhythm, and no obvious murmurs in the apical area. The abdomen was flat and soft, without tenderness and rebound pain, and the liver and spleen were not palpable below the costal margin. Murphy’s sign was negative. There was no percussion pain in bilateral kidney area and no tenderness in bilateral ureter running area. There was no edema in both lower limbs. Neurological tests were negative.

The patient had an increased lactic dehydrogenase of 255 U/L (upper limit: 250 U/L). Blood tests, hepatic function tests, and other biochemical tests were within normal limits.

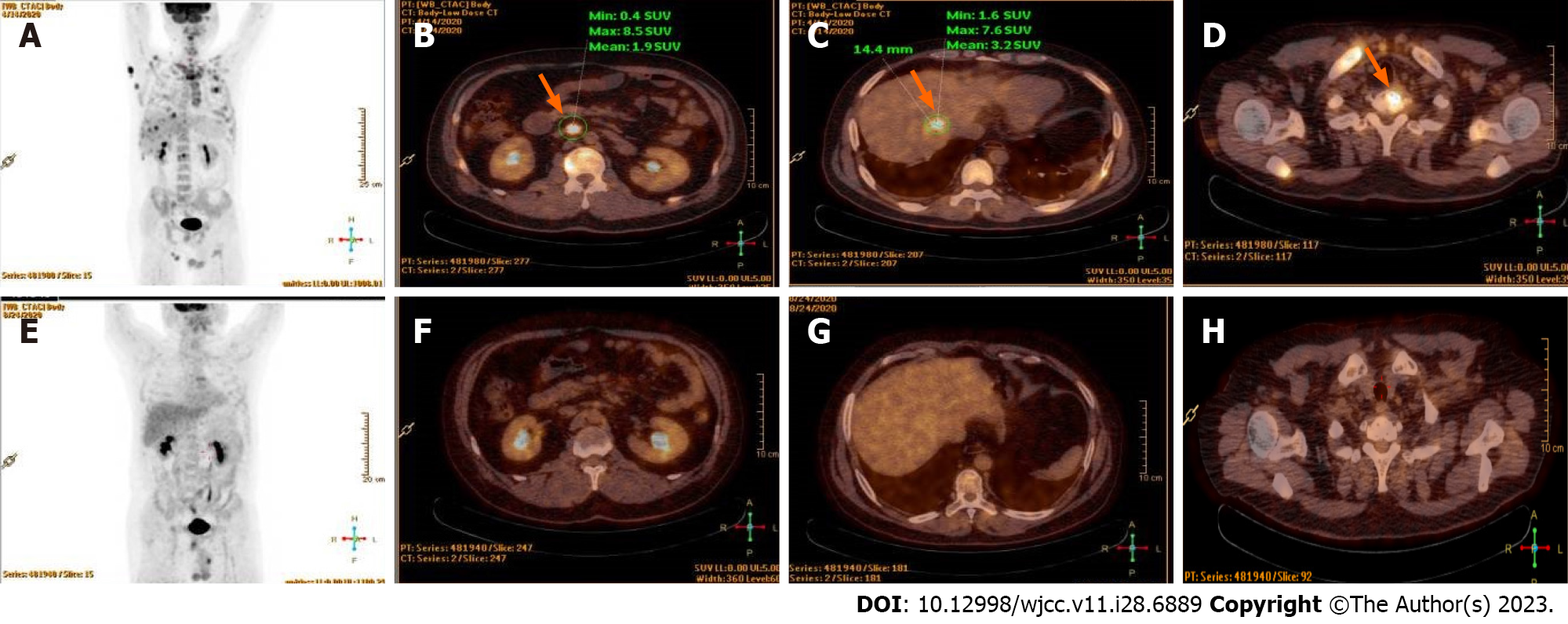

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan revealed the subcutaneous nodule on the back as tumor invasion since there was higher 18F-flurodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) uptake activity, and also involvement of liver, bone, right lung, and widespread lymph nodes (Figure 2A–D).

Systemic ALK-negative ALCL, Stage IV group B.

DICE chemotherapeutic regimen (ifosfamide 1000 mg/m2, cisplatin 25 mg/m2, etoposide 60 mg/m2, dexamethasone 9 mg/m2) combined with chidamide (30 mg, 2 d a week for 2 wk) instead of brentuximab was administered, due to the patient’s economic conditions. Complete response was achieved after four cycles of this regimen (Figure 2E–H). Then, he underwent ASCT. Cyclophosphamide 2 g/m2 and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor 8 µg/kg/d were given to promote hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) mobilization from the bone marrow to the peripheral blood. HSCs were collected in a dose of mononuclear cells 9.46 × 108/kg, CD34+ 1.86 × 106/kg. Then BEAM preparative regimen (carmustine 300 mg/m2, cytarabine 150 mg/m2, etoposide 100 mg/m2, melphalan 140 mg/m2) was administered. Neutrophil engraftment occurred on Day +11 and platelet engraftment occurred on Day +14. As maintenance therapy, chidamide (20 mg, two days a week) was administered, without occurrence of adverse events.

The patient has been in complete remission for 12 mo until the last follow up in November 2021. This is similar to the progression-free survival of 12 mo, as reported in the literature[6].

PC-ALCL is sensitive to drugs; however, it has a high relapse rate with some studies reporting a rate of 42%[4]. Patients with early cutaneous relapse have a poorer 5-year specific survival (64%) than those with late or no relapse (96%)[7]. Multiple skin tumors in one limb and extracutaneous disease when this disease has progressed, are individual factors associated with poorer outcomes[8]. This case had both these two poor prognostic factors.

We used immunohistochemistry (IHC) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to further study the molecular mechanism of transition of this cutaneous ALCL to sALCL. We found the proliferation index Ki-67 was significantly high (80%) when the primary cutaneous disease occurred (Figure 1F). Furthermore, Ki67 was subsequently upregulated when this disease progressed into sALCL (95% on first relapse, Figure 1M; 90% on second relapse, Figure 1O). It is abnormal to find this indicator in indolent lymphomas, especially in a disease with a good prognosis, such as primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The Ki-67 index was less than 45% in 82.8% of indolent lymphomas, and we can differentiate indolent lymphomas from aggressive ones with the cut-off value of 45%[9]. Ki-67 is also an independent adverse prognostic factor in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas[10].

For this case, we found that interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) break was obvious and was consistently associated with the disease process on FISH (80% on first relapse, Figure 1N; 70% on second relapse, Figure 1P), which represented the DUSP22-IRF4 rearrangement. Recurrent rearrangement of the DUSP22-IRF4 locus on chromosome 6p25.3 is related to a favorable prognosis in systemic ALK-negative ALCL, with a 5-year OS rate of 80%–90%, similar to that of ALK-positive ALCL[11,12]. This is much better than that of the other two subtypes of ALK-negative ALCL; 42% for triple negative (ALK, DUSP22, and TP63 rearrangements), 17% for TP63-rearranged[13]. DUSP22 rearrangement results in decreased expression of dual-specificity phosphatase-22, decreased STAT3 activation, and decreased activity of immune and autoimmune-mediated mechanisms regulated by T-cells[14]. DUSP22-IRF4 translocation was identified in 20%–57% of the cases of PC-ALCL[15]. A panel of cases of PC-ALCL with DUSP22–IRF4 Locus translocations had features with a distinctive biphasic histopathological pattern, with small cerebriform lymphocytes in the epidermis, and larger transformed lymphocytes in the dermis[16]. However, we know little about the independent influence of DUSP22–IRF4 rearrangement on prognosis in PC-ALCL.

This case was initially diagnosed as primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma through histopathological features and IHC parameters, including CD30, ALK, CD3, CD4, CD8, GRB, TIA-1, EMA, CD20, PAX5, CD10, and BCL6. The patient progressed to sALCL, which has rarely been reported. Three clinical features in this patient, including cutaneous relapse, multiple skin tumors in one limb, and extracutaneous disease are poor prognosis factors, according to the literature. High Ki-67 expression in this case is a potential poor prognosis marker, indicating need for more aggressive therapy when present in PC-ALCL. There is a need for more retrospective case control studies for further evaluation.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Hematology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Alkhatib AJ, Jordan; Goebel WS, United States; Shahriari M, Iran S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Willemze R, Cerroni L, Kempf W, Berti E, Facchetti F, Swerdlow SH, Jaffe ES. The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2019;133:1703-1714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 512] [Cited by in RCA: 837] [Article Influence: 139.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, Attygalle AD, Araujo IBO, Berti E, Bhagat G, Borges AM, Boyer D, Calaminici M, Chadburn A, Chan JKC, Cheuk W, Chng WJ, Choi JK, Chuang SS, Coupland SE, Czader M, Dave SS, de Jong D, Du MQ, Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Ferry J, Geyer J, Gratzinger D, Guitart J, Gujral S, Harris M, Harrison CJ, Hartmann S, Hochhaus A, Jansen PM, Karube K, Kempf W, Khoury J, Kimura H, Klapper W, Kovach AE, Kumar S, Lazar AJ, Lazzi S, Leoncini L, Leung N, Leventaki V, Li XQ, Lim MS, Liu WP, Louissaint A Jr, Marcogliese A, Medeiros LJ, Michal M, Miranda RN, Mitteldorf C, Montes-Moreno S, Morice W, Nardi V, Naresh KN, Natkunam Y, Ng SB, Oschlies I, Ott G, Parrens M, Pulitzer M, Rajkumar SV, Rawstron AC, Rech K, Rosenwald A, Said J, Sarkozy C, Sayed S, Saygin C, Schuh A, Sewell W, Siebert R, Sohani AR, Tooze R, Traverse-Glehen A, Vega F, Vergier B, Wechalekar AD, Wood B, Xerri L, Xiao W. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36:1720-1748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 1888] [Article Influence: 629.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bekkenk MW, Geelen FA, van Voorst Vader PC, Heule F, Geerts ML, van Vloten WA, Meijer CJ, Willemze R. Primary and secondary cutaneous CD30(+) lymphoproliferative disorders: a report from the Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Group on the long-term follow-up data of 219 patients and guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 2000;95:3653-3661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 535] [Cited by in RCA: 465] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu HL, Hoppe RT, Kohler S, Harvell JD, Reddy S, Kim YH. CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders: the Stanford experience in lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1049-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Popova TN, Radinov A, Stavrov K, Temelkova I, Terziev I, Lozev I, Lukanova D, Mangarov H, Wollina U, Tchernev G. Primary Cutaneous CD30+/ALK- ALCL with Transition into sALCL: Favourable Response after Systemic Administration with Brentuximab Vedotin! Unique Presentation in a Bulgarian Patient! Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6:1275-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fu C, Yang C, Li Q, Wang L, Zou L. Glans metastatic extra-nodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal-type with HDAC inhibitor as maintenance therapy: a rare case report with literature review. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9:3602-3608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fernández-de-Misa R, Hernández-Machín B, Combalía A, García Muret MP, Servitje O, Muniesa C, Gallardo F, Pujol RM, Martí RM, Ortiz-Brugués A, Maroñas-Jiménez L, Ortiz-Romero PL, Blanch Rius L, Izu R, Román C, Cañueto J, Blanes M, Morillo M, Bastida J, Peñate Y, Pérez Gala S, Espinosa Lara P, Pérez Gil A, Estrach T. Prognostic factors in patients with primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a multicentric, retrospective analysis of the Spanish Group of Cutaneous Lymphoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:762-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Benner MF, Willemze R. Applicability and prognostic value of the new TNM classification system in 135 patients with primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1399-1404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Broyde A, Boycov O, Strenov Y, Okon E, Shpilberg O, Bairey O. Role and prognostic significance of the Ki-67 index in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:338-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mitani S, Tango T, Sonobe Y, Baba N, Nagatani T, Nomoto S, Mori S. Expression of three cell proliferation-associated antigens, DNA polymerase alpha, Ki-67 antigen and transferrin receptor in nodal and cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Int J Hematol. 1991;54:385-393. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Pedersen MB, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Bendix K, Ketterling RP, Bedroske PP, Luoma IM, Sattler CA, Boddicker RL, Bennani NN, Nørgaard P, Møller MB, Steiniche T, d'Amore F, Feldman AL. DUSP22 and TP63 rearrangements predict outcome of ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a Danish cohort study. Blood. 2017;130:554-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Savage KJ, Slack GW. DUSP22-rearranged ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma is a pathogenetically distinct disease but can have variable clinical outcome. Haematologica. 2023;108:1463-1467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Parrilla Castellar ER, Jaffe ES, Said JW, Swerdlow SH, Ketterling RP, Knudson RA, Sidhu JS, Hsi ED, Karikehalli S, Jiang L, Vasmatzis G, Gibson SE, Ondrejka S, Nicolae A, Grogg KL, Allmer C, Ristow KM, Wilson WH, Macon WR, Law ME, Cerhan JR, Habermann TM, Ansell SM, Dogan A, Maurer MJ, Feldman AL. ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma is a genetically heterogeneous disease with widely disparate clinical outcomes. Blood. 2014;124:1473-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Pina-Oviedo S. Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma-A Review of Clinical, Morphological, Immunohistochemical, and Molecular Features. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wada DA, Law ME, Hsi ED, Dicaudo DJ, Ma L, Lim MS, Souza Ad, Comfere NI, Weenig RH, Macon WR, Erickson LA, Ozsan N, Ansell SM, Dogan A, Feldman AL. Specificity of IRF4 translocations for primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a multicenter study of 204 skin biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:596-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Onaindia A, Montes-Moreno S, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Batlle A, González de Villambrosía S, Rodríguez AM, Alegre V, Bermúdez GM, González-Vela C, Piris MA. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphomas with 6p25.3 rearrangement exhibit particular histological features. Histopathology. 2015;66:846-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |