Published online Oct 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i28.6864

Peer-review started: June 26, 2023

First decision: August 4, 2023

Revised: August 10, 2023

Accepted: August 21, 2023

Article in press: August 21, 2023

Published online: October 6, 2023

Processing time: 90 Days and 18.1 Hours

Congenital agenesis of the gallbladder (CAGB) is a rare condition often misdiagnosed as cholecystolithiasis, leading to unnecessary surgeries. Accurate diagnosis and surgical exploration are crucial in patients with suspected CAGB or atypical gallbladder stone symptoms. Preoperative imaging, such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), plays a vital role in confirming the diagnosis. Careful intraoperative dissection is necessary to avoid iatrogenic injuries and misdiagnosis. Multidisciplinary consultations and collaboration, along with the use of various diagnostic methods, can minimize associated risks.

We present the case of a 34-year-old female with suspected gallbladder stones, ultimately diagnosed with CAGB through surgical exploration. The patient underwent laparoscopic examination followed by open exploratory surgery, which confirmed absence of the gallbladder. Subsequent imaging studies supported the diagnosis. The patient received appropriate postoperative care and experienced a successful recovery.

This case highlights the rarity of CAGB and the importance of considering this condition in the differential diagnosis of patients with gallbladder stone symptoms. Accurate diagnosis using preoperative imaging, such as MRCP, is crucial to prevent unnecessary surgeries. Surgeons should exercise caution and conduct meticulous dissection during surgery to avoid iatrogenic injuries and ensure accurate diagnosis. Multidisciplinary collaboration and utilization of various diagnostic methods are essential to minimize the risk of misdiagnosis. Selection of the optimal treatment strategy should prioritize minimizing trauma and maintaining open communication with the patient and their family members.

Core Tip: Congenital agenesis of the gallbladder (CAGB) is a rare condition often misdiagnosed as cholecystolithiasis, leading to unnecessary surgeries. It is crucial for healthcare professionals to consider the possibility of CAGB in patients with suspected gallbladder stones or atypical presentations. Preoperative imaging, such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, plays a vital role in confirming the diagnosis and preventing misdiagnosis. Surgeons should exercise caution during surgery to avoid iatrogenic injuries and ensure accurate diagnosis. Multidisciplinary collaboration and the use of various diagnostic methods are essential to minimize the risk of misdiagnosis and unnecessary surgical interventions. Minimizing trauma and maintaining open communication with the patient and their family members are key factors in the treatment strategy.

- Citation: Sun HJ, Ge F, Si Y, Wang Z, Sun HB. Importance of accurate diagnosis of congenital agenesis of the gallbladder from atypical gallbladder stone presentations: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(28): 6864-6870

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i28/6864.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i28.6864

Congenital agenesis of the gallbladder (CAGB) is an extremely rare congenital anomaly characterized by absence of the gallbladder[1,2]. This condition is often misdiagnosed as cholecystolithiasis due to similar clinical presentations, leading to unnecessary surgical interventions[3,4]. The incidence of CAGB is remarkably low, making it a challenging condition to diagnose accurately[5]. In cases of suspected gallbladder stones, it is crucial for healthcare professionals to consider the possibility of CAGB to avoid unnecessary surgical procedures. Preoperative imaging techniques, such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), play a vital role in confirming the diagnosis and preventing misdiagnosis[6]. Surgical exploration is often necessary to confirm absence of the gallbladder in cases of suspected CAGB. Careful dissection and thorough anatomical evaluation are essential to avoid iatrogenic injuries and to provide an accurate diagnosis[7].

This case report presents a patient with a history of suspected gallbladder stones, who was ultimately diagnosed with CAGB through surgical exploration. The report highlights the significance of accurate diagnosis, appropriate preoperative imaging, and careful surgical evaluation in patients with suspected CAGB. Through this case report, we aim to raise awareness about the rarity of CAGB and emphasize the importance of considering this condition in the differential diagnosis of patients with gallbladder stone symptoms. Additionally, we discuss the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration and the use of various diagnostic methods to minimize the risk of misdiagnosis and unnecessary surgical interventions.

A 34-year-old woman presented with the complaint of having discovered gallbladder stones one month prior to admission.

The woman reported a history of discovering gallbladder stones during a routine medical examination one month before her admission. However, she did not experience any noticeable symptoms such as chills, fever, nausea, vomiting, hematemesis, acid reflux, belching, chest discomfort, or palpitations. Despite the incidental finding of gallbladder stones, she remained asymptomatic throughout this period and did not receive any specific treatment.

The patient's medical history was significant for the absence of hypertension or any other chronic diseases. She denied a history of infectious diseases such as hepatitis, tuberculosis, or malaria. In terms of surgical history, the patient had undergone a previous cesarean section and appendectomy.

No special notes.

The patient appeared to be in overall good general health. The vital signs were stable, with a normal body temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate. Upon inspection, the patient's abdomen was flat and symmetrical, without any visible abnormalities or deformities. The abdominal wall showed no signs of distension, erythema, or discoloration. No visible pulsations or visible peristaltic waves were observed. Palpation of the abdomen revealed a soft and non-tender abdomen without any palpable masses or organomegaly. No guarding, rigidity, or rebound tenderness was noted. The liver and spleen were non-palpable, and there were no palpable masses or lymphadenopathy in the abdominal region. Auscultation of bowel sounds revealed normal bowel motility with regular and audible bowel sounds in all quadrants of the abdomen. No abnormal or bruit-like sounds were detected. During the examination, the patient did not demonstrate any signs of jaundice. There were no palpable gallbladder or renal tenderness. The patient did not exhibit any peripheral edema or signs of fluid retention.

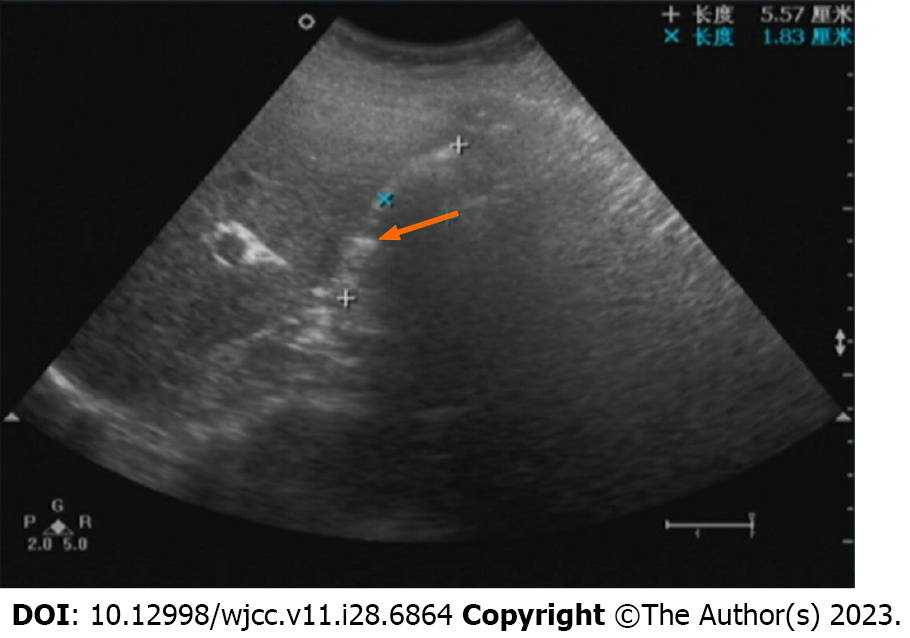

Ultrasonography before surgery: An ultrasound was performed before surgery and showed that the gallbladder was filled with a strong hyperechoic mass of uncertain size. A wider echogenic band was seen behind the mass, while the posterior half and posterior wall of the gallbladder were not visualized. Color Doppler flow imaging (CDFI) showed dot-like blood flow signals in the gallbladder wall. Liver echogenicity was increased (Figure 1). These results indicated gallbladder inflammation and gallstones (filled type).

Ultrasonography after surgery: An ultrasound was performed after surgery and showed that the gallbladder was filled with a strong echogenic mass, the size of which was unclear (Figure 2A). A wider echogenic band was seen behind it, while the posterior half and posterior wall of the gallbladder were not visualized. CDFI showed dot-like blood flow signals in the gallbladder wall. The gallbladder was not visualized (please consider the medical history). There was the possibility of a small amount of fluid accumulation in the gallbladder area (Figure 2B).

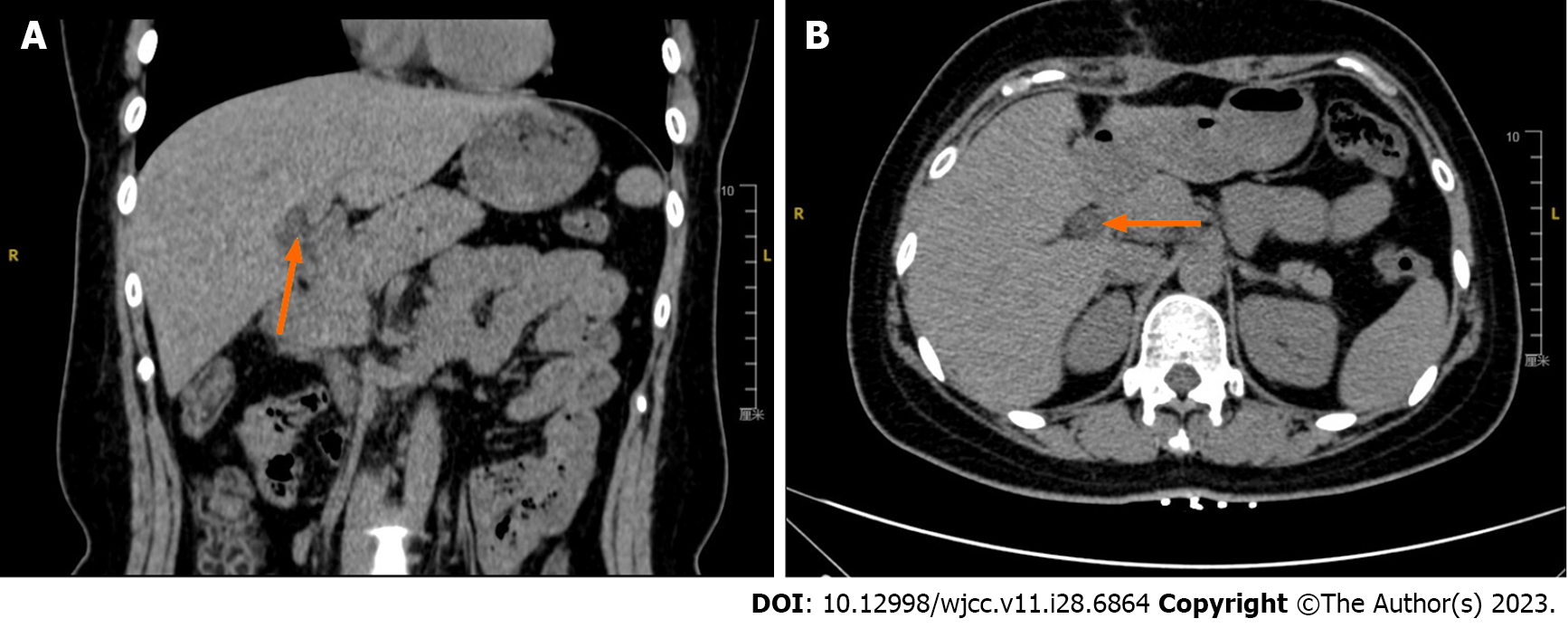

Computed tomography scan: Computed tomography (CT) scan (coronal and transverse planes) was performed after surgery to further assess the patient's condition. The CT scan revealed no clear demonstration of a normal gallbladder structure. Additionally, it showed mild fatty liver and dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts (Figure 3A). However, the normal structure of the gallbladder was not clearly visualized. In the gallbladder fossa region, there was a linear, slightly higher density shadow (Figure 3B).

MRCP: MRCP was also conducted to obtain detailed images of the biliary system. The MRCP imaging revealed an indistinctly visualized gallbladder fossa with no evidence of a gallbladder or cystic duct (Figure 4A). There was dilation of the bile ducts at the porta hepatis (hepatic hilum), and the common bile duct appeared irregular in thickness with suboptimal local contrast enhancement (Figure 4B).

The patient underwent several imaging examinations to aid in the diagnosis and evaluation of her condition.

The final diagnosis in this case was CAGB. The diagnosis was confirmed during surgical exploration, where absence of the gallbladder was observed. The patient's history of suspected gallbladder stones, combined with imaging findings and intraoperative findings, supported the diagnosis of CAGB. This diagnosis highlights the importance of considering congenital anomalies in cases of atypical gallbladder stone presentations and the significance of accurate diagnosis to avoid unnecessary surgical interventions. The confirmation of CAGB provides important insights into the patient's condition, which will guide future management and follow-up care. It is crucial to inform the patient and their family about the diagnosis and its implications to ensure appropriate treatment and support.

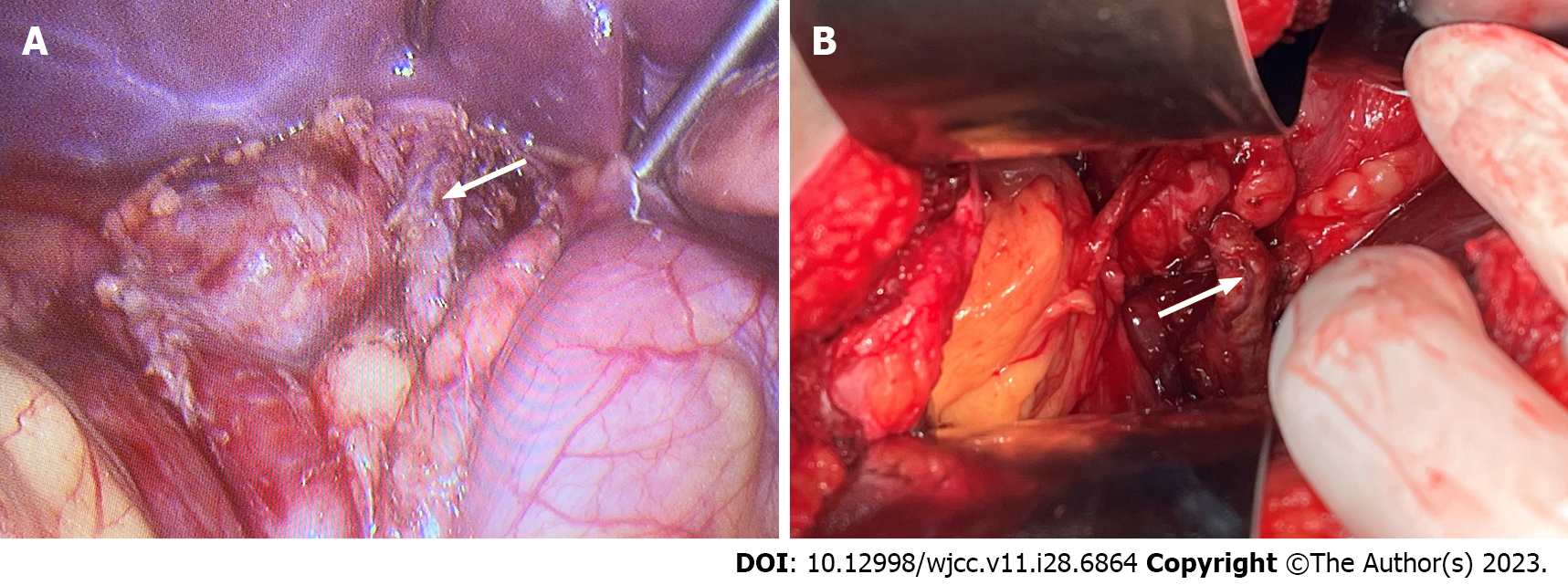

General anesthesia was successfully induced, and the patient was placed into the supine position. Routine skin preparation was performed with iodine solution, and sterile drapes were applied. A 1 cm skin incision was made above the umbilicus, and an Veress needle was inserted into the abdomen for insufflation of carbon dioxide gas to achieve a pressure of 13 mmHg. A 1 cm trocar was then inserted under direct vision, followed by making a 1 cm incision 2 cm below the xiphoid process, and making a 0.5 cm incision 2 cm below the midline of the right clavicle at the costal margin. A 1 cm trocar and a 0.5 cm trocar were inserted through these incisions along with the surgical instruments. Intraoperatively, the stomach and liver were found to be adhered, and the adhesions were carefully dissected. No gallbladder was visualized. The hepatoduodenal ligament was dissected, and the common bile duct was completely freed (Figure 5A). The wall of the common bile duct appeared slightly thickened, with a diameter of approximately 0.8 cm, but the gallbladder was still not identified (Figure 5B). It was decided to proceed with an open exploratory laparotomy. A 12 cm incision was made below the right costal margin, and the abdomen was entered. Further adhesiolysis was performed, and the hepatoduodenal ligament was completely freed. The common bile duct, portal vein, and hepatic artery were dissected and confirmed that no gallbladder was present (Figure 3). Intraoperative consultation with B-mode ultrasound further confirmed absence of the gallbladder (Figure 4). Based on the intraoperative observations, a diagnosis of CAGB was established. The case was discussed with the Director and after communicating with the patient's family, it was decided to proceed with exploratory laparotomy only.

No active bleeding was observed during the exploration. The surgical site was treated with hemostatic powder, and a drain (Benoist and Medo) was placed in Winslow's foramen and subcutaneously. No specimen was sent for pathological examination. The abdominal fascia was closed with interrupted sutures using polydioxanone synthetic absorbable suture, followed by layered closure of the subcutaneous tissue. A subcutaneous drain was inserted, and the skin was closed with skin staples.

Minimal intraoperative bleeding was encountered, and the anesthesia was satisfactory. The patient recovered well and was transferred to the postoperative ward. Surgical incision classification: Grade II/A.

Following the diagnosis of CAGB, the patient received postoperative care aimed at managing inflammation and preserving liver function. The treatment approach focused on general supportive measures, including pain management and ensuring proper wound healing. The patient was closely monitored for any postoperative complications, and regular follow-up visits were scheduled to assess her recovery and overall well-being. The medical team provided appropriate counseling and education regarding lifestyle modifications and dietary considerations. In addition to the specific treatment for CAGB, the patient was advised to maintain a healthy lifestyle, including regular exercise and a balanced diet. Emphasis was placed on the importance of maintaining a healthy weight and avoiding excessive consumption of fatty foods to prevent potential complications related to absence of the gallbladder.

During the follow-up period, the patient's condition remained stable, with no signs of recurrent cholecystitis or related symptoms. The treatment approach focused on providing adequate support and addressing any concerns or questions the patient had regarding her condition. It is important to note that the treatment for CAGB primarily involves managing symptoms and potential complications rather than curing the underlying congenital anomaly. Regular follow-up and ongoing medical care are necessary to ensure the patient's well-being and to address any potential issues that may arise in the future.

CAGB is an extremely rare congenital anomaly characterized by absence of the gallbladder[8,9]. Due to its rarity and atypical presentation, CAGB often poses a diagnostic challenge and can be easily misdiagnosed as cholecystitis or other gallbladder disorders[3,10,11]. This case report highlights the significance of accurate diagnosis, appropriate preoperative imaging, and careful surgical evaluation in patients with suspected CAGB. In this case, the patient presented with incidental findings of gallbladder stones during routine medical examination but remained asymptomatic. The initial misdiagnosis of cholecystitis based on ultrasound findings highlights the importance of considering CAGB as a possible differential diagnosis in patients without typical symptoms of gallbladder disease[1]. Accurate preoperative imaging, such as MRCP, played a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis of CAGB in this case[7]. MRCP is a non-invasive imaging modality that allows for detailed visualization of the biliary tree and can help identify absence of the gallbladder[12]. When examining patients with full gallstone through B-ultrasonography, it is important to be aware of the possibility of gallbladder agenesis. Preoperative MRCP examination can be employed to obtain more accurate diagnostic results, and if deemed necessary, surgical exploration can be conducted to definitively ascertain the presence or absence of the gallbladder. In this case, laparoscopic examination initially failed to identify the gallbladder, and the procedure was converted to open exploratory surgery. Meticulous dissection and anatomical evaluation were essential to avoid iatrogenic injuries and provide an accurate diagnosis[4]. The importance of multidisciplinary collaboration and the use of various diagnostic methods cannot be overstated in cases of suspected CAGB. In this case, the involvement of different specialties, including radiology, surgery, and pathology, contributed to a comprehensive assessment and accurate diagnosis[13]. Multidisciplinary consultations and the exchange of expertise can significantly reduce the risk of misdiagnosis and unnecessary surgical interventions[14]. It is crucial for healthcare professionals to be aware of the rarity of CAGB and its atypical presentation to avoid unnecessary surgical procedures and provide appropriate management for patients[15]. Increasing awareness about CAGB among clinicians and emphasizing the use of preoperative imaging techniques, such as MRCP, can aid in accurate diagnosis and prevent misdiagnosis[16,17]. The ultimate treatment strategy for CAGB focuses on managing symptoms and potential complications rather than curing the underlying anomaly. Minimizing trauma during surgery, providing adequate postoperative care, and maintaining open communication with the patient and their family members are essential components of the treatment approach. Further research and case studies are warranted to enhance our understanding of this rare anomaly and its clinical implications. Sharing such cases through case reports can contribute to medical knowledge, raise awareness among healthcare professionals, and improve patient care by facilitating accurate diagnosis and appropriate management of CAGB.

CAGB is a rare congenital abnormality that can present with atypical symptoms and often poses a diagnostic challenge. This case report emphasizes the importance of accurate diagnosis, appropriate preoperative imaging, and meticulous surgical evaluation in patients with suspected CAGB. The utilization of imaging techniques such as MRCP played a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis of CAGB. Additionally, multidisciplinary collaboration among different specialties, including radiology, surgery, and pathology, contributed to a comprehensive assessment and accurate diagnosis. It is essential for healthcare professionals to be aware of the rarity of CAGB and its atypical presentation to avoid unnecessary surgical procedures and provide appropriate management. The treatment strategy for CAGB focuses on symptom management and minimizing potential complications rather than curing the underlying anomaly. Further research and case studies are needed to enhance our understanding of this rare anomaly and its clinical implications, contributing to improved patient care through accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Pathology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hunasanahalli Giriyappa V, India; Oley MH, Indonesia S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Kim JS, Lee HJ, Koo EJ. Prenatally diagnosed congenital agenesis of the gallbladder: A case report. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2022;84. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bennion RS, Thompson JE Jr, Tompkins RK. Agenesis of the gallbladder without extrahepatic biliary atresia. Arch Surg. 1988;123:1257-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Salazar MC, Brownson KE, Nadzam GS, Duffy A, Roberts KE. Gallbladder Agenesis: A Case Report. Yale J Biol Med. 2018;91:237-241. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Joliat GR, Shubert CR, Farley DR. Isolated congenital agenesis of the gallbladder and cystic duct: report of a case. J Surg Educ. 2013;70:117-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Malde S. Gallbladder agenesis diagnosed intra-operatively: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Miller JC, Harisinghani M, Richter JM, Thrall JH, Lee SI. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. J Am Coll Radiol. 2007;4:133-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kabiri H, Domingo OH, Tzarnas CD. Agenesis of the gallbladder. Curr Surg. 2006;63:104-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rivera A, Williamson D, Almonte G. Preoperative Diagnosis of Gallbladder Agenesis: A Case Report. Cureus. 2022;14:e30753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cho CH, Suh KW, Min JS, Kim CK. Congenital absence of gallbladder. Yonsei Med J. 1992;33:364-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Deo KB, Avudaiappan M, Shenvi S, Kalra N, Nada R, Rana SS, Gupta R. Misdiagnosis of carcinoma gall bladder in endemic regions. BMC Surg. 2022;22:343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Serour F, Klin B, Strauss S, Vinograd I. False-positive ultrasonography in agenesis of the gallbladder: a pitfall in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy approach. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1993;3:144-146. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Maccioni F, Martinelli M, Al Ansari N, Kagarmanova A, De Marco V, Zippi M, Marini M. Magnetic resonance cholangiography: past, present and future: a review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010;14:721-725. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Portale G, Mazzeo A, Cipollari C, Isoardi R, Spolverato Y, Zuin M, Fiscon V. Missing the main actor: Intra-operative diagnosis of agenesis of the gallbladder - When late is not 'too' late. J Minim Access Surg. 2023;19:141-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kaushik SP. Current perspectives in gallbladder carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:848-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Biesterveld BE, Alam HB. Evidence-Based Management of Calculous Biliary Disease for the Acute Care Surgeon. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2021;22:121-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Maurea S, Caleo O, Mollica C, Imbriaco M, Mainenti PP, Palumbo C, Mancini M, Camera L, Salvatore M. Comparative diagnostic evaluation with MR cholangiopancreatography, ultrasonography and CT in patients with pancreatobiliary disease. Radiol Med. 2009;114:390-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sahni VA, Mortele KJ. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography: current use and future applications. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:967-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |