Published online Oct 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i28.6812

Peer-review started: May 26, 2023

First decision: August 24, 2023

Revised: September 1, 2023

Accepted: September 11, 2023

Article in press: September 11, 2023

Published online: October 6, 2023

Processing time: 122 Days and 5.7 Hours

Skin cancer is a common malignant tumor in dermatology. A large area must be excised to ensure a negative incisal margin on huge frontotemporal skin cancer, and it is difficult to treat the wound. In the past, treatment with skin grafting and pressure dressing was easy to cause complications such as wound infections, subcutaneous effusion, skin necrosis, and contracture. Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has been applied to treat huge frontotemporal skin cancer.

Herein, we report the case of a 92-year-old woman with huge frontotemporal skin cancer. The patient presented to the surgery department complaining of ruptured bleeding and pain in a right frontal mass. The tumor was pathologically diagnosed as highly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. The patient underwent skin cancer surgery and skin grafting, after which NPWT was used. She did not experience a relapse during the three-year follow-up period.

NPWT is of great clinical value in the postoperative treatment of skin cancer. It is not only inexpensive but also can effectively reduce the risk of surgical effusion, infection, and flap necrosis.

Core Tip: The most common types of skin cancer include cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), cutaneous basal cell carcinoma, and cutaneous malignant melanoma. The main treatment options are surgery and radiotherapy. We report a 92-year-old woman with skin cancer who had a 4 cm × 5 cm mass on the right forehead. A pathological examination of the right frontal mass confirmed the diagnosis of highly differentiated SCC. After surgical treatment, Negative pressure wound therapy was adjunct. We found that this technology helps to reduce the risk of surgical effusion, infection, and flap necrosis. No recurrence was observed during the three-year follow-up. The patient is still alive.

- Citation: Huang GS, Xu KC. Application of negative pressure wound therapy after skin grafting in the treatment of skin cancer: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(28): 6812-6816

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i28/6812.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i28.6812

Skin cancer is a prevalent malignant condition worldwide. Fair skin and long-term exposure to ultraviolet B rays are the most important risk factors[1]. Therefore, early preventative measures mainly involve avoiding sun exposure and tanning beds[1]. Reducing the recurrence rate and improving skin-graft survival in the treatment of skin cancer are challenging[1]. The current treatments for skin cancer include surgery, radiation, cryotherapy, Mohs chemotherapy, electrotherapy, and some topical ointments and dressings as additional options[2]. Although surgical modalities remain the mainstay treatment, new research and fresh innovation are still needed to reduce morbidity and mortality[3].

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has been widely utilized in skin grafting and surgical wound healing[4]. However, reports on its clinical application following skin cancer surgery are limited. In contrast to previous reports on the cost-utility value[5] and the effect of NPWT in reducing lymphatic leakage[6] in skin cancer, we found that this technology helps to reduce the risk of surgical effusion, infection, and flap necrosis.

A 92-year-old woman presented to the surgery department complaining of ruptured bleeding and pain in a right frontal mass for two weeks.

Symptoms started two weeks before presentation with ruptured bleeding and pain in a right frontal mass.

The patient had hypertension for more than seven years and had taken amlodipine besylate tablets for a long time. The patient's self-reported blood pressure control was satisfactory. The patient had a right frontal mass one year ago, which was about the size of a grain of rice, with no obvious cause. Because it did not adversely affect her, she did not pay attention to it, and the lump gradually increased in size. The tumor increased significantly in the recent five months to about 4 cm × 5 cm in size.

The patient denied any family history of skin cancer.

On physical examination, the vital signs were as follows: Body temperature, 37.1℃; blood pressure, 148/54 mmHg; heart rate, 63 beats per min; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths per min. A ruptured mass, with a diameter of 4 cm, was found on the right forehead. There was no discharge of pus or significant bleeding.

Routine blood levels were normal (red blood cell count, 3.49 × 1012 PCS/L; hemoglobin, 106 g/L; mean platelet volume, 10.7 fL; and platelet volume distribution width, 12.1%). Serum hormone levels were also normal (total triiodothyronine, 0.76 ng/mL; thyrotropin, 7.35 μIU/L). Urinalysis findings were normal (hematuria, +; leukocyte esterase, ++; white blood cell count, +).

Computed tomography examination of the lungs revealed calcified nodules in the lower lobe of the left lung and a calcified aortic wall. B-ultrasound examination revealed multiple calcifications of the liver, gallstones, and cysts in both kidneys.

The mass appeared to be deep and subcutaneous fat layer. During surgery, the base of the mass and the surrounding skin were completely excised along a circumference of 2 cm. A pathological examination of the right frontal mass confirmed the diagnosis of highly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Rapid pathologic examination showed that the operative margin was negative.

Combined with the patient's medical history and pathological examination, the final diagnosis was skin cancer.

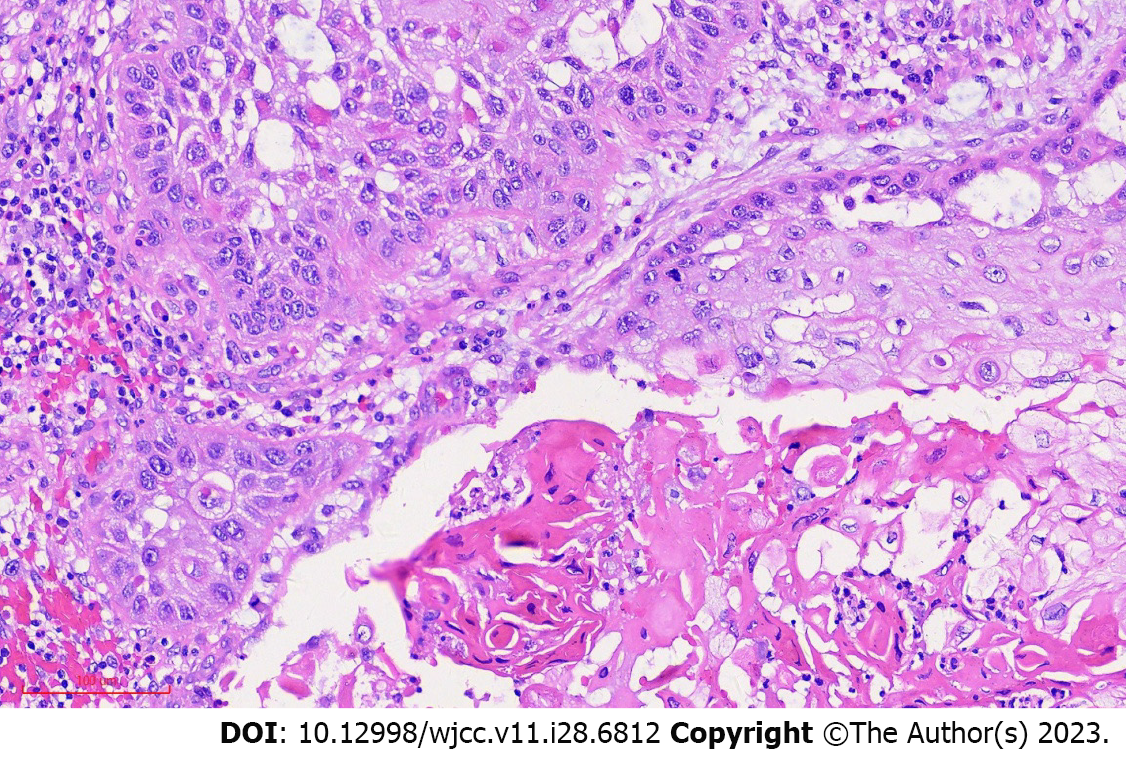

We successfully implemented NPWT following skin grafting to treat a 92-year-old woman with skin cancer. The patient presented with a cauliflower-shaped mass measuring 4.0 cm × 5.0 cm on the right frontotemporal region. The mass had been present for two years and ulcerated for one month (Figure 1A). The biopsy results showed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC, Figure 2). The patient had a seven-year history of hypertension and was being treated with Captopril. After completing the relevant examinations, the patient underwent radical skin cancer surgery with skin grafting under local anesthesia, followed by NPWT.

The treatment process steps were as follows (Figure 1): (1) The tumor size and the longest and shortest meridians were measured (Figures 1A and B); (2) The donor region for a skin graft of the same size was identified in the relaxed skin area of the abdomen; (3) The tumor was completely excised with a 2 cm margin from the cut edge. The use of an electric knife was avoided to prevent thermal damage to the incisional margin. This approach was employed to reduce the risk of graft necrosis and scar formation; (4) Intraoperative pathology was quickly performed to assess the incisional margins. Meanwhile, the skin graft was excised from the donor site. The subcutaneous fat of the graft was removed into physiological saline, and multiple small holes were made on the graft using a sharp knife. This technique allowed for beneficial negative pressure suction, thereby preventing subcutaneous fluid accumulation and ensuring tight adherence of the skin graft to the wound surface, promoting graft survival (Figure 1C). (5) The graft was sutured intermittently onto the wound (Figure 1C); and (6) External sealed negative pressure was applied at 15 KPa. Negative pressure was discontinued after seven days, and a regular bandage was applied (Figure 1D). The postoperative pathological report of the mass showed highly differentiated SCC with a negative margin. No recurrence was observed during the three-year follow-up (Figure 1E).

The patient was free of recurrence and still alive three years after surgery.

Skin cancer includes basal cell carcinoma and SCC[1]. SCC comprises approximately 16% of skin cancer cases. It predominantly manifests near the ears, on the vermilion border of the lips, and in scars. SCC is prone to metastasizing and may require extensive surgical intervention[7]. Treatment of large SCC tumors with infiltrative growth is challenging. Due to the large size of the tumor and the limited laxity of the forehead and facial skin, adherence to surgical standards necessitates the removal of a 2 cm margin around the tumor. Consequently, a notable amount of skin is lost in the surgical area, necessitating skin grafting from the abdomen. Graft survival after transplantation is a primary concern for doctors. NPWT is an efficient drainage technique that has emerged in recent years to fully drain and promote wound healing[8]. It can reduce the risk of infection, improve local microcirculation, increase the oxygen content of the wound tissue, promote the growth of granulation tissue, and significantly expedite healing[9,10]. Negative pressure drainage facilitates the timely removal of exudate and necrotic tissue from the drainage area, thereby suppressing aggregation and any infection in the wound, stimulating the rapid and optimal growth of granulation tissue, and accelerating wound healing. This technique also facilitates blood transport to the wound, exerting pressure to create a close fit between the graft and the wound without any gap, thereby ensuring a normal blood supply. Continuous negative pressure suction facilitates the continuous transfer of bodily fluids from the wound to the drainage tube, thereby providing effective and continuous auxiliary power for the wound surface. Additionally, it effectively prevents the formation of dead spaces.

The patient in this case underwent skin grafting with the assurance of a negative surgical margin and benefitted from the above advantages, thereby achieving a favorable outcome. Conventional skin grafting typically involves the use of pressure bandages. However, the pressure provided by these bandages is uneven, and the skin graft cannot fully adhere to the wound tissue. Insufficient pressure on the edges of the graft can result in loose areas between the graft and wound and, in turn, impaired angiogenesis, ischemic necrosis of the graft, subcutaneous fluid accumulation, and wound infection. Considering these issues, it was decided to use NPWT for this patient. She did not experience relapse during the three-year follow-up period, confirming the beneficial effect of NPWT in this case.

We thank Dr. Huang Gaoshi for his assistance in the three-year follow-up and the pathology department of the hospital for the histopathological analysis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Jinhua Science and Technology Bureau, No. 2020–4-177.

Specialty type: Dermatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Moshref RH, Saudi Arabia S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Linares MA, Zakaria A, Nizran P. Skin Cancer. Prim Care. 2015;42:645-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Goto H, Kiyohara Y, Shindo M, Yamamoto O. Symptoms of and Palliative Treatment for Unresectable Skin Cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Simões MCF, Sousa JJS, Pais AACC. Skin cancer and new treatment perspectives: a review. Cancer Lett. 2015;357:8-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Webster J, Scuffham P, Sherriff KL, Stankiewicz M, Chaboyer WP. Negative pressure wound therapy for skin grafts and surgical wounds healing by primary intention. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;CD009261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ker H, Al-Murrani A, Rolfe G, Martin R. WOUND Study: A Cost-Utility Analysis of Negative Pressure Wound Therapy After Split-Skin Grafting for Lower Limb Skin Cancer. J Surg Res. 2019;235:308-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Poirier A, Albuisson E, Bihain F, Granel-Brocard F, Perez M. Does Preventive Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT) reduce local complications following Lymph Node Dissection (LND) in the management of metastatic skin tumors? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2022;75:4403-4409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gordon R. Skin cancer: an overview of epidemiology and risk factors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2013;29:160-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huang C, Leavitt T, Bayer LR, Orgill DP. Effect of negative pressure wound therapy on wound healing. Curr Probl Surg. 2014;51:301-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Faust E, Opoku-Agyeman JL, Behnam AB. Use of Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy With Instillation and Dwell Time: An Overview. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147:16S-26S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Song YP, Wang L, Yuan BF, Shen HW, Du L, Cai JY, Chen HL. Negative-pressure wound therapy for III/IV pressure injuries: A meta-analysis. Wound Repair Regen. 2021;29:20-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |