Published online Oct 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i28.6763

Peer-review started: June 20, 2023

First decision: July 7, 2023

Revised: July 13, 2023

Accepted: August 29, 2023

Article in press: August 29, 2023

Published online: October 6, 2023

Processing time: 97 Days and 3.6 Hours

Uterine fibroids, are prevalent benign tumors affecting women of reproductive age. However, surgical treatment is often necessary for symptomatic hysteromyoma cases. This study examines the impact of humanized nursing care on reducing negative emotions and postoperative complications in patients receiving hysteromyoma surgery.

To investigate the impact of humanized nursing care on patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery.

Among patients who underwent hysteromyoma surgery at the Fudan University Affiliated Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, 200 were randomly assigned to either the control group (n = 100) or the humanized nursing care group (n = 100). The control group received traditional nursing care, while the humanized nursing care group received a comprehensive care plan encompassing psychological support, pain management, and tailored rehabilitation programs. In addition, anxiety and depression levels were assessed using the hospital anxiety and depression scale preoperatively and postoperatively. Postoperative complications were evaluated during follow-up assessments and compared between both groups.

The humanized nursing care group demonstrated a significant decrease in anxiety and depression levels compared to the control group (P < 0.05). The rate of postoperative complications, including infection, bleeding, and deep venous thrombosis, was also markedly lower in the humanized nursing care group (P < 0.05).

Humanized nursing care can effectively alleviate negative emotions and reduce the incidence of postoperative complications in patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery. This approach should be considered a crucial component of perioperative care for these patients. Further research may be needed to explore additional benefits and long-term outcomes of implementing humanized nursing care in this population.

Core Tip: Humanized nursing care can effectively alleviate negative emotions and reduce postoperative complications in patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery, as observed in this study. The approach included psychological support, pain management, and tailored rehabilitation programs. Moreover, the study highlights the importance of adopting a patient-centered approach to care that emphasizes effective communication, shared decision-making, and establishing a therapeutic relationship between nurses and patients. The findings suggest that healthcare providers should consider humanized nursing care as an essential component of perioperative care for these patients. Further research is needed to explore the long-term effects of implementing humanized nursing care and its additional benefits in diverse patient populations in various surgical settings.

- Citation: Liu L, Xiao YH, Zhou XH. Effects of humanized nursing care on negative emotions and complications in patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(28): 6763-6773

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i28/6763.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i28.6763

Uterine fibroids, also known as hysteromyomas, are common benign tumors affecting 20%-40% of women of reproductive age[1]. These benign smooth muscle tumors originate from the uterine wall and can vary in size, number, and location. Hysteromyomas can be categorized into three types based on their location: submucosal, intramural, and subserosal[2]. Symptoms associated with uterine fibroids include heavy menstrual bleeding, pelvic pain, frequent urination, constipation, and fertility problems that significantly affect many women's quality of life[3].

Depending on the size, location, and severity of symptoms, surgical intervention may be necessary for patients with symptomatic hysteromyoma. Surgical approaches include myomectomy, hysterectomy, and laparoscopic or robotic-assisted surgery[4]. However, despite advances in surgical techniques, patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery often grapple with significant stress and anxiety due to uncertainties surrounding the procedure, potential complications, fertility preservation, and postoperative recovery[5].

Surgery can be a significant source of stress and anxiety for patients, contributing to poor emotional well-being and increasing the risk of postoperative complications[6]. Additionally, several studies have reported that patients with high preoperative anxiety levels are more likely to experience increased pain, prolonged hospital stays, and a higher incidence of postoperative complications[7]. As a result, negative emotions postoperatively, such as anxiety and depression, can impair immune function and wound healing, which may further increase the risk of complications and delay recovery[8].

Recent years have seen a growing recognition of holistic patient care that encompasses both the physical aspects of a patient's condition and their psychological, emotional, and social needs. Humanized nursing care emphasizes the human aspects of care and seeks to create a supportive and therapeutic environment for patients, and has been increasingly recognized as a valuable approach to improving patient outcomes[9]. Humanized nursing care encompasses various interventions, such as providing psychological support, individualized pain management, and customized rehabilitation programs, which aim to enhance patient satisfaction and promote a better quality of life after surgery[10].

Several studies have documented the beneficial effects of humanized nursing care on patient outcomes across a variety of clinical settings, such as oncology, orthopedics, and cardiovascular surgery[11]. For example, humanized nursing has been shown to reduce anxiety and depression, improve pain control, and enhance patient satisfaction in cancer treatment patients[12]. Similarly, humanized nursing has been associated with improved functional outcomes and reduced complications in patients undergoing joint replacement surgery[13]. However, the effects of humanized nursing on negative emotions and postoperative complications in patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery remain unclear. Given the potential benefits of humanized nursing care in other clinical settings, exploring its effects on the emotional well-being and postoperative outcomes of patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery is necessary. This insight could drive the development of evidence-based, patient-centered care strategies for this patient population[14,15].

This study aims to examine the impact of humanized nursing care on the negative emotions and postoperative complications experienced by patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery. We hypothesize that humanized nursing care will be associated with a significant decrease in negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression [measured by the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)], and a reduced occurrence of postoperative complications compared to traditional nursing care. This study aims to illuminate the role of humanized nursing care in the perioperative management of hysteromyoma surgery, thereby contributing to the creation of optimal care strategies for these patients. Moreover, the study's findings could facilitate the development and implementation of humanized nursing care interventions across diverse surgical settings, aligning with the overarching goal of delivering high-quality, patient-centered care[16,17].

This single-center, prospective, randomized controlled trial was conducted among patients who underwent hysteromyoma surgery at the Fudan University Affiliated Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital. Two hundred patients were randomly assigned to either the control group (n = 100) or the humanized nursing care group (n = 100). The control group received traditional nursing care, while the humanized nursing care group received a comprehensive care plan encompassing psychological support, pain management, and tailored rehabilitation programs. In addition, anxiety and depression levels were assessed using the HADS preoperatively and postoperatively. Postoperative complications were evaluated during follow-up assessments and compared between both groups from January 2021 to December 2022. Patients undergoing elective hysteromyoma surgery were assigned to the control or humanized nursing care groups. Institutional review board approved the study protocol, and all participants signed written informed consent forms before enrollment. The study was conducted per the Declaration of Helsinki and was registered with a clinical trial registry.

Of the patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery, 200 were enrolled for a follow-up analysis in this study. Patients aged between 18 and 60 years, who had a confirmed diagnosis of hysteromyoma through imaging examinations, were awaiting elective surgery, and provided informed consent, were included in this study. Patients with a history of psychiatric disorders or substance abuse, severe concurrent medical conditions (e.g., uncontrolled diabetes or hypertension), prior hysteromyoma surgery, or those that had ineffective communication with the research team were excluded from the study.

Participants were placed in either the control or humanized nursing care groups, using a computer-generated randomization sequence with an allocation ratio of 1:1. Randomization was stratified by age and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification. While the research team and nurses administering interventions were aware of the group allocations, patients, surgeons, and data collection and analysis personnel were blinded to this information.

The control group received conventional nursing care, which included routine perioperative care, such as preoperative education, pain management, and postoperative care. Preoperative education was provided by the nursing staff and focused on the surgical procedure, potential risks and complications, and postoperative care instructions. Pain management consisted of administering analgesics according to a standardized protocol based on the World Health Organization pain ladder. Postoperative care included monitoring vital signs, wound care, early mobilization, and patient education regarding self-care and follow-up appointments.

The humanized nursing care group received a comprehensive care plan incorporating psychological support, individualized pain management, and customized rehabilitation programs. The interventions were designed based on humanized nursing care principles, emphasizing empathy, active listening, and a supportive therapeutic environment. The specific interventions included:

Psychological support: Patients in the humanized nursing care group were provided emotional support by the nursing staff, who were trained in effective communication techniques and principles of psychological counseling. Support sessions were conducted preoperatively and postoperatively, during which patients were encouraged to express their fears, concerns, and expectations. The nursing staff also provided information about the surgical procedure, potential complications, and postoperative recovery in a manner tailored to each patient's needs and preferences.

Individualized pain management: Pain management in the humanized nursing care group was tailored to each patient's needs and preferences. The nursing staff assessed pain levels using a visual analog scale and adjusted analgesic administration accordingly. Beyond pharmacological interventions, patients were offered non-pharmacological pain relief options, including relaxation techniques, guided imagery, and music therapy.

Customized rehabilitation programs: Postoperative rehabilitation programs were designed for each patient based on their needs, functional status, and preferences. The programs included tailored exercises to improve mobility and strength and patient education on self-care, wound care, and coping strategies for managing postoperative symptoms.

The study's primary outcome measured changes in anxiety and depression levels before and after surgery using the HADS. The HADS is a validated, self-report questionnaire comprising 14 items, split evenly between anxiety and depression. Each item is scored on a four-point Likert scale, providing a total score ranging from 0 to 21 for each subscale. Higher scores indicate greater anxiety or depression levels. The HADS is often used in clinical settings to evaluate patients' emotional well-being during surgery.

The secondary outcome was the incidence of postoperative complications, including infection, bleeding, and deep venous thrombosis. Postoperative complications were assessed by the research team based on clinical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging studies, as appropriate. The research team followed a standardized protocol for diagnosing and managing postoperative complications based on established guidelines and best practices.

We collected baseline data from the patient's medical records, encompassing factors such as age, body mass index (BMI), the size and location of the hysteromyoma, and the ASA physical status classification. Preoperative HADS scores were obtained during the preoperative assessment, and postoperative HADS scores were obtained on the 3rd postoperative day. In addition, data on postoperative complications were collected from the patient's medical records and through follow-up assessments conducted by the research team.

We used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 22.0 to analyze the data. Baseline characteristics between the two groups were compared via chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. In addition, independent t-tests and chi-square tests were employed to compare changes in HADS scores and postoperative complication incidence, respectively, between the two groups. A P value less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Additionally, we performed subgroup analyses to scrutinize potential effect modifiers, such as age, BMI, and the size and location of uterine fibroids.

In this study, we initially enrolled 200 patients and randomly assigned them to either a control group (n = 100) or a humanized nursing care group (n = 100). However, by the end of the study, only 193 patients had completed the program: 96 in the control group and 97 in the humanized nursing care group. This was due to the unfortunate loss of seven patients to follow-up; four from the control group and three from the humanized nursing care group withdrew their consent or were lost due to personal reasons (Figure 1).

No significant differences were found in the baseline characteristics between the two groups, including age, BMI, the size and location of hysteromyomas, and the ASA physical status classification (Table 1). On average, the participants were 42.3-years-old [standard deviation (SD) = 7.6] with a mean BMI of 24.7 kg/m2 (SD = 4.1). Most participants had intramural hysteromyomas (62.2%), followed by submucosal (21.8%) and subserosal (16.0%) types.

| Characteristic | Control group, n = 100 | Humanized nursing care group, n = 100 | P value |

| Age in yr | 46.2 ± 6.5 | 45.8 ± 6.7 | 0.76 |

| Body mass index in kg/m² | 24.3 ± 3.2 | 24.1 ± 3.4 | 0.81 |

| Hysteromyoma size in cm | 5.4 ± 1.8 | 5.5 ± 1.9 | 0.87 |

| Hysteromyoma location | 0.95 | ||

| Submucosal | 25 | 24 | |

| Intramural | 55 | 56 | |

| Subserosal | 20 | 20 | |

| ASA physical status | 0.83 | ||

| Class I | 42 | 45 | |

| Class II | 50 | 48 | |

| Class III | 8 | 7 |

Next, we aimed to assess the effect of humanized nursing care on patient anxiety. Compared to the control group, the humanized nursing care group displayed a significant decrease in postoperative HADS anxiety scores [mean difference (MD) = -2.7, 95%CI: -3.6 to -1.8, P < 0.001). Similarly, the humanized nursing care group experienced a significant reduction in postoperative HADS depression scores in comparison to the control group (MD = -2.3, 95%CI: -3.1 to -1.5, P < 0.001) (Table 2). Together, these data show that humanized nursing care significantly lowered postoperative complications and reduced negative emotions.

| Group | HADS anxiety score | HADS depression score |

| Control group, n = 100 | 10.5 ± 2.6 | 9.8 ± 2.3 |

| Humanized nursing care group, n = 100 | 7.8 ± 2.1 | 7.5 ± 2.0 |

Subsequently, we investigated the influence of humanized nursing care on postoperative complications. The humanized nursing care group demonstrated a significantly reduced incidence of postoperative complications compared to the control group (12.4% vs 26.0%, P = 0.006). Specifically, the humanized nursing care group exhibited fewer instances of infection (4.1% vs 12.5%, P = 0.017), bleeding (3.1% vs 8.3%, P = 0.049), and deep venous thrombosis (5.2% vs 13.5%, P = 0.029) (Table 3). No reported serious adverse events were linked to the interventions during the study. Patients in the humanized nursing care group tolerated the interventions well, and no participant discontinued due to adverse events.

| Complication | Control group, n = 100 | Humanized nursing care group, n = 100 | P value |

| Overall complications | 26 | 12.4 | 0.006 |

| Infection | 12.5 | 4.1 | 0.017 |

| Bleeding | 8.3 | 3.1 | 0.049 |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 13.5 | 5.2 | 0.029 |

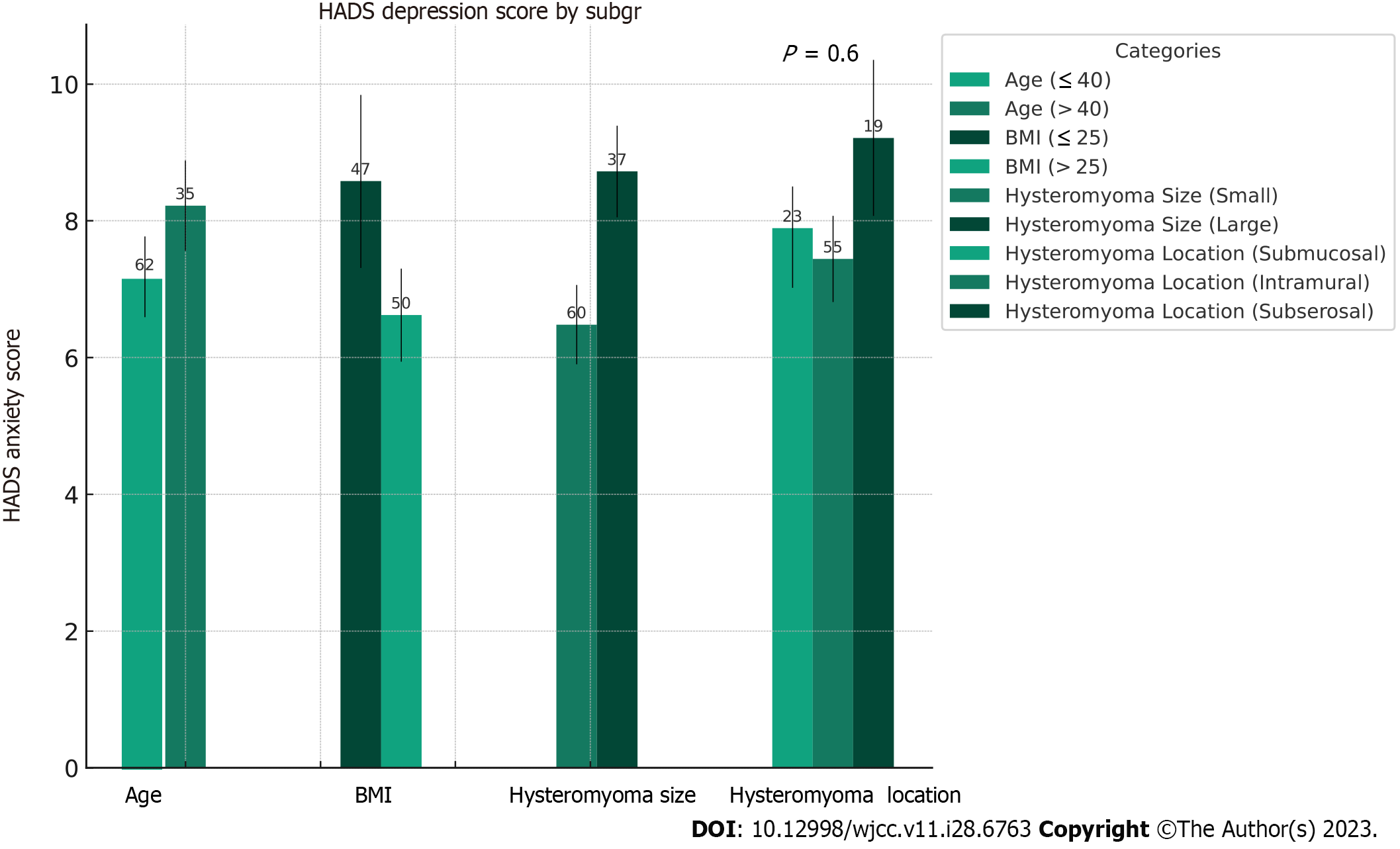

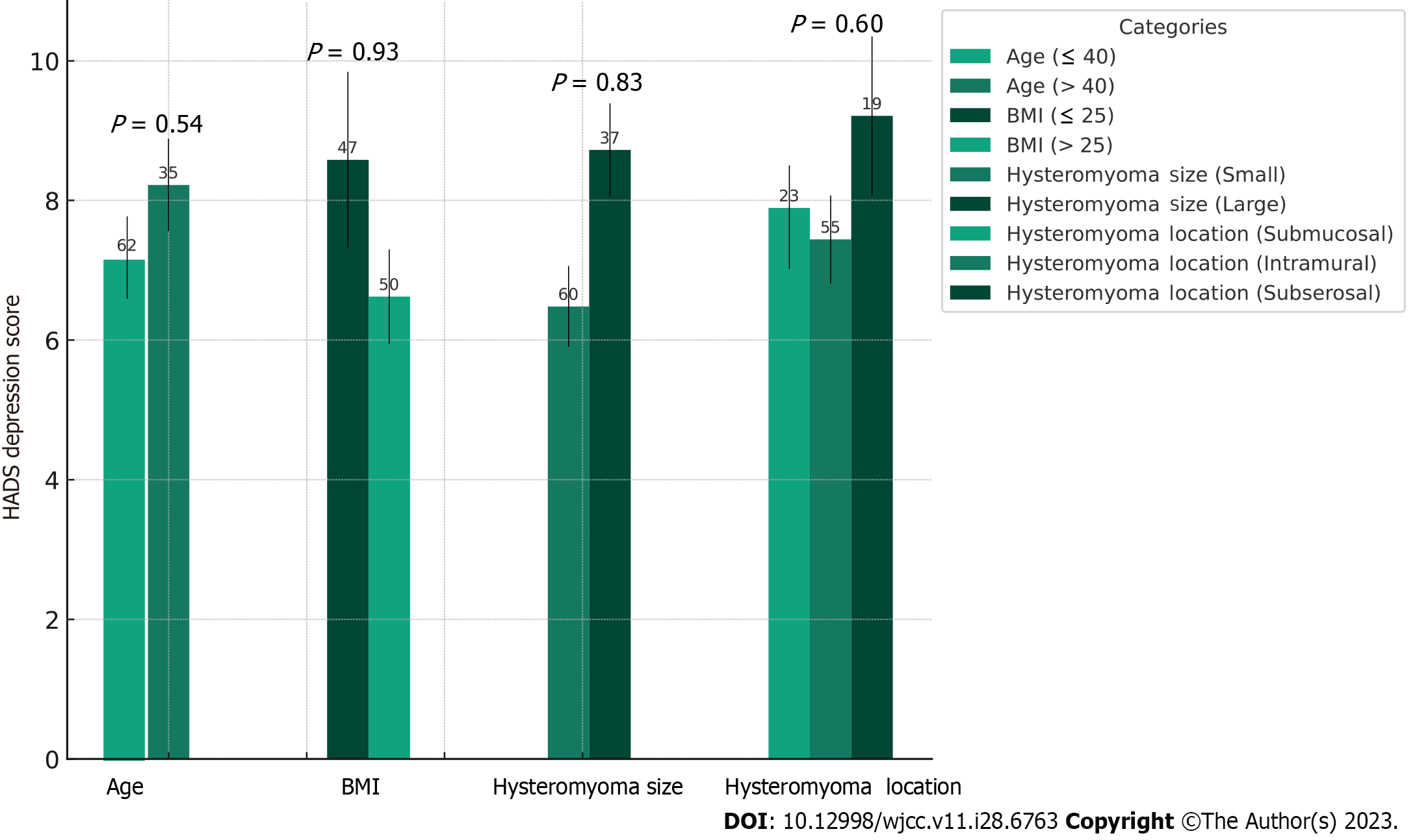

The advantageous impacts of humanized nursing care on reducing negative emotions and the incidence of postoperative complications were uniform across various subgroups, defined by age, BMI, and the size and location of the hysteromyoma (Figures 2 and 3). Furthermore, no substantial interactions were detected between the effects of the treatment and these subgroup variables, implying these factors did not significantly alter the benefits of humanized nursing care.

Our study found that humanized nursing care significantly reduced negative emotions and postoperative complications among patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting the effectiveness of humanized nursing care in improving patient outcomes and enhancing the overall quality of care in surgical settings.

The observed improvement in negative emotions in the group receiving humanized nursing care can be attributed to several factors. First, providing psychological support, including emotional support and tailored information about the surgery and recovery process, may have helped patients better understand their condition and cope with their fears and concerns. This observation aligns with previous research showing that psychological support can reduce anxiety and depression in surgery patients[18,19]. Second, the individualized pain management approach and pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions may have led to more effective pain relief and reduced negative emotions. This is consistent with previous studies demonstrating the benefits of individualized pain management on patient satisfaction and emotional well-being[20]. Third, the use of customized rehabilitation programs, focused on enhancing mobility and self-care skills, may have fostered a sense of control and self-efficacy, further mitigating negative emotions[21].

We observed a reduced risk of postoperative infection in the humanized nursing care group, which could be attributed to the improved emotional well-being of patients and the parallel positive impact on their immune function[22,23]. Furthermore, individualized pain management, a component of the humanized nursing approach, could facilitate early mobilization in patients after surgery, potentially reducing the risk of complications such as deep venous thrombosis and bleeding[24,25]. Furthermore, to decrease the likelihood of these complications, a customized rehabilitation program could help patients comply with postoperative care instructions and self-care practices[26,27].

One of the key components of humanized nursing care is establishing a therapeutic relationship between the nurse and the patient. Based on empathy, trust, and respect, this relationship can provide a supportive environment for patients to express their emotions, concerns, and needs[28,29]. In our study, the nursing staff was trained to engage in active listening, demonstrate empathy, and respond to the patient's emotional cues, which may have contributed to the observed improvements in negative emotions. In addition, the therapeutic relationship may also facilitate patient adherence to the postoperative care plan, as patients may be more likely to follow the advice and recommendations of healthcare providers they trust[30,31].

Another facet of the humanized nursing approach is patient-centered care, where the care plan is tailored to the patient's individual needs, preferences, and values[32,33]. In our study, for instance, the nursing staff conducted comprehensive assessments of each patient's physical, psychological, and social needs, collaborating with the multidisciplinary team to develop individualized care plans. This patient-centered approach may have contributed to the observed improvements in negative emotions and postoperative complications, as it enabled the nursing staff to address each patient's unique needs and concerns and provide more targeted interventions[34,35].

Furthermore, the humanized nursing care approach emphasizes the importance of effective communication and shared decision-making throughout the care process[36]. In our study, the nursing staff communicated with the patients and their families clearly, concisely, and empathetically, ensuring they understood the information provided and were actively involved in the decision-making process. This collaborative approach may have empowered the patients, increasing satisfaction and engagement in their care and contributing to improved emotional well-being and postoperative outcomes[37].

Some limitations of our study should be acknowledged. The single-center design and the relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study focused on the short-term effects of humanized nursing care on negative emotions and postoperative complications, and further research is needed to explore the long-term effects on patient outcomes.

Despite these limitations, our study presents valuable evidence that supports the effectiveness of humanized nursing care in enhancing emotional well-being and improving postoperative outcomes among patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery. In addition, our findings highlight the need for healthcare providers to adopt a more holistic, patient-centered approach to managing patients with hysteromyoma and other surgical conditions. Future research should investigate the long-term effects of humanized nursing care on patient outcomes through longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes and more diverse patient populations in various surgical settings.

Uterine fibroids, prevalent benign tumors in women of reproductive age, often require surgical treatment for symptomatic cases like hysteromyoma. This study aimed to assess the impact of humanized nursing care on negative emotions and postoperative complications in patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery. The humanized nursing care group exhibited significant reductions in anxiety and depression levels and a lower rate of postoperative complications compared to the control group. These findings highlight the effectiveness of humanized nursing care in alleviating negative emotions and reducing postoperative complications, emphasizing its importance in perioperative care for these patients. Further investigation is necessary to explore additional benefits and long-term outcomes associated with the implementation of humanized nursing care in this population.

The motivation for this study stemmed from the need to improve the care and outcomes of patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery. Uterine fibroids are common benign tumors that can significantly impact a woman's quality of life, necessitating surgical intervention for symptomatic cases. Recognizing the importance of comprehensive patient care, this study aimed to investigate the impact of humanized nursing care on reducing negative emotions and postoperative complications in these patients.

The main objectives of this study were to investigate the impact of humanized nursing care on patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery and to evaluate its effects on reducing negative emotions and postoperative complications. Specifically, the researchers aimed to compare the outcomes between the humanized nursing care group and the control group receiving traditional nursing care. The study sought to assess changes in anxiety and depression levels through preoperative and postoperative evaluations using the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS). Additionally, the researchers aimed to evaluate the incidence of postoperative complications, including infection, bleeding, and deep venous thrombosis, during follow-up assessments. By focusing on these objectives, the researchers aimed to determine whether implementing a comprehensive care plan encompassing psychological support, pain management, and tailored rehabilitation programs could effectively alleviate negative emotions and reduce postoperative complications in patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery. The findings would provide valuable insights into the potential benefits of humanized nursing care and contribute to improving perioperative care for this patient population.

This study employed a randomized controlled trial design at the Fudan University Affiliated Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital. Two hundred patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery were randomly assigned to either the control group (n = 100) or the humanized nursing care group (n = 100). The control group received traditional nursing care, while the humanized nursing care group received comprehensive care including psychological support, pain management, and tailored rehabilitation programs. Anxiety and depression levels were assessed using the HADS preoperatively and postoperatively. Postoperative complications were evaluated during follow-up assessments and compared between the two groups. Statistical analysis was conducted to determine significant differences.

The research findings revealed significant positive outcomes associated with the implementation of humanized nursing care in patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery. The humanized nursing care group showed a notable decrease in anxiety and depression levels compared to the control group, indicating the effectiveness of this approach in alleviating negative emotions. Additionally, the humanized nursing care group exhibited a significantly lower rate of postoperative complications, including infection, bleeding, and deep venous thrombosis. These results contribute to the existing research in the field by emphasizing the importance of comprehensive patient care that extends beyond the surgical procedure itself. By integrating psychological support, pain management, and tailored rehabilitation programs, humanized nursing care demonstrated its potential to improve patient outcomes and well-being in the perioperative period. However, some unresolved issues remain. Further research is needed to explore additional benefits and long-term outcomes associated with implementing humanized nursing care in this specific population. Long-term follow-up assessments are necessary to evaluate the sustained effects of this care approach on patients' emotional well-being and postoperative recovery. Additionally, studies examining cost-effectiveness and feasibility of implementing humanized nursing care on a broader scale would provide valuable insights for healthcare institutions and policymakers.

The importance of integrating humanized nursing care as a crucial component of perioperative care for patients with hysteromyoma. By addressing the holistic needs of patients throughout their surgical journey, healthcare providers can enhance emotional well-being and improve overall patient outcomes. However, further research is needed to explore additional benefits and long-term outcomes associated with implementing humanized nursing care in this specific population. Such investigations would provide valuable insights for optimizing perioperative care and improving the overall quality of life for patients undergoing hysteromyoma surgery.

The findings of this study provide valuable perspectives for future research in the field of nursing care for hysteromyoma surgery patients. Firstly, further investigations should explore the mechanisms by which humanized nursing care interventions alleviate negative emotions and reduce postoperative complications. Understanding the specific components and approaches within humanized nursing care that contribute to these positive outcomes can inform the development of targeted interventions. Secondly, long-term follow-up studies are warranted to evaluate the sustained effects of humanized nursing care on patient well-being beyond the immediate postoperative period. Assessing patient outcomes, quality of life, and the potential for recurrence or long-term complications would provide a comprehensive understanding of the impact of humanized nursing care over time.

Over the course of my researching and writing this paper, I would like to express my thanks to all those who have helped me.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Nursing

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Andreasson A, Sweden; Bertuccio RF, United States S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Stewart EA, Cookson CL, Gandolfo RA, Schulze-Rath R. Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: a systematic review. BJOG. 2017;124:1501-1512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 679] [Cited by in RCA: 562] [Article Influence: 70.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Donnez J, Dolmans MM. Uterine fibroid management: from the present to the future. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22:665-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 382] [Cited by in RCA: 409] [Article Influence: 45.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cardozo ER, Clark AD, Banks NK, Henne MB, Stegmann BJ, Segars JH. The estimated annual cost of uterine leiomyomata in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:211.e1-211.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 473] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Peddada SD, Laughlin SK, Miner K, Guyon JP, Haneke K, Vahdat HL, Semelka RC, Kowalik A, Armao D, Davis B, Baird DD. Growth of uterine leiomyomata among premenopausal black and white women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19887-19892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vilos GA, Allaire C, Laberge PY, Leyland N; SPECIAL CONTRIBUTORS. The management of uterine leiomyomas. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37:157-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mitchell M. Patient anxiety and modern elective surgery: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:806-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Caumo W, Schmidt AP, Schneider CN, Bergmann J, Iwamoto CW, Bandeira D, Ferreira MB. Risk factors for preoperative anxiety in adults. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:298-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Page GG, Marucha PT, MacCallum RC, Glaser R. Psychological influences on surgical recovery. Perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Am Psychol. 1998;53:1209-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McCance T, McCormack B, Dewing J. An exploration of person-centredness in practice. Online J Issues Nurs. 2011;16:1. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Papastavrou E, Efstathiou G, Tsangari H, Suhonen R, Leino-Kilpi H, Patiraki E, Karlou C, Balogh Z, Palese A, Tomietto M, Jarosova D, Merkouris A. A cross-cultural study of the concept of caring through behaviours: patients' and nurses' perspectives in six different EU countries. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:1026-1037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Olsson LE, Hansson E, Ekman I, Karlsson J. A cost-effectiveness study of a patient-centred integrated care pathway. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65:1626-1635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, Moore M, Rydall A, Rodin G, Tannock I, Donner A, Lo C. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721-1730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1089] [Cited by in RCA: 1234] [Article Influence: 112.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McDonald S, Hetrick S, Green S. Pre-operative education for hip or knee replacement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;CD003526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Coulter A, Entwistle VA, Eccles A, Ryan S, Shepperd S, Perera R. Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD010523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28548] [Cited by in RCA: 31694] [Article Influence: 754.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:759-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3042] [Cited by in RCA: 3122] [Article Influence: 183.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; Consort Group. [CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials (Chinese version)]. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2010;8:604-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Carr E, Brockbank K, Allen S, Strike P. Patterns and frequency of anxiety in women undergoing gynaecological surgery. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:341-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141:343-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 671] [Cited by in RCA: 825] [Article Influence: 63.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Eccleston C, Fisher E, Craig L, Duggan GB, Rosser BA, Keogh E. Psychological therapies (Internet-delivered) for the management of chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD010152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chiang LC, Chen WC, Dai YT, Ho YL. The effectiveness of telehealth care on caregiver burden, mastery of stress, and family function among family caregivers of heart failure patients: a quasi-experimental study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:1230-1242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:601-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2019] [Cited by in RCA: 1762] [Article Influence: 83.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Marsland AL, Walsh C, Lockwood K, John-Henderson NA. The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating and stimulated inflammatory markers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;64:208-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in RCA: 456] [Article Influence: 57.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Westby MD, Brittain A, Backman CL. Expert consensus on best practices for post-acute rehabilitation after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a Canada and United States Delphi study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66:411-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S. Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery: fast-track experience in 712 patients. Acta Orthop. 2008;79:168-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 427] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Timmers T, Janssen L, van der Weegen W, Das D, Marijnissen WJ, Hannink G, van der Zwaard BC, Plat A, Thomassen B, Swen JW, Kool RB, Lambers Heerspink FO. The Effect of an App for Day-to-Day Postoperative Care Education on Patients With Total Knee Replacement: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7:e15323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Slade SC, Kent P, Patel S, Bucknall T, Buchbinder R. Barriers to Primary Care Clinician Adherence to Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Metasynthesis of Qualitative Studies. Clin J Pain. 2016;32:800-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | McCabe C. Nurse-patient communication: an exploration of patients' experiences. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:41-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, Slonska Z, Brand H; (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3835] [Cited by in RCA: 2774] [Article Influence: 213.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1830] [Cited by in RCA: 1598] [Article Influence: 99.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients' adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42:200-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1384] [Cited by in RCA: 1474] [Article Influence: 70.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Epstein RM, Street RL Jr. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:100-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 923] [Cited by in RCA: 1079] [Article Influence: 77.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:229-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bechtel C, Ness DL. If you build it, will they come? Designing truly patient-centered health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:914-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:780-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2000] [Cited by in RCA: 2218] [Article Influence: 170.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, Jorgenson S, Sadigh G, Sikorskii A, Lewin S, Smith RC, Coffey J, Olomu A. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Street RL Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:295-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1316] [Cited by in RCA: 1439] [Article Influence: 89.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |