Published online Sep 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i27.6531

Peer-review started: June 1, 2023

First decision: August 2, 2023

Revised: August 10, 2023

Accepted: August 23, 2023

Article in press: August 23, 2023

Published online: September 26, 2023

Processing time: 111 Days and 1.9 Hours

Veno-arterial extra corporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) support is commonly complicated with left ventricle (LV) distension in patients with cardiogenic shock. We resolved this problem by transeptally converting VA-ECMO to left atrium veno-arterial (LAVA)-ECMO that functioned as a temporary paracorporeal left ventricular assist device to resolve LV distension. In our case LAVA-ECMO was also functioning as a bridge-to-transplant device, a technique that has been scarcely reported in the literature.

A 65 year-old man suffered from acute myocardial injury that required percutaneous stents. Less than two weeks later, noncompliance to antiplatelet therapy led to stent thrombosis, cardiogenic shock, and cardiac arrest. Femoro-femoral VA-ECMO support was started, and the patient underwent a second coronary angiography with re-stenting and intra-aortic balloon pump placement. The VA-ECMO support was complicated by left ventricular distension which we resolved via LAVA-ECMO. Unfortunately, episodes of bleeding and sepsis complicated the clinical picture and the patient passed away 27 d after initiating VA-ECMO.

This clinical case demonstrates that LAVA-ECMO is a viable strategy to unload the LV without another invasive percutaneous or surgical procedure. We also demonstrate that LAVA-ECMO can also be weaned to a left ventricular assist device system. A benefit of this technique is that the procedure is potentially reversible, should the patient require VA-ECMO support again. A transeptal LV venting approach like LAVA-ECMO may be indicated over ImpellaTM in cases where less LV unloading is required and where a restrictive myocardium could cause LV suctioning. Left ventricular over-distention is a well-known complication of peripheral VA-ECMO in cardiogenic shock and LAVA ECMO through transeptal cannulation offers a novel and safe approach for treating LV overloading, without the need of an additional percutaneous access.

Core Tip: We report a clinical case of a 65-year-old man with cardiogenic shock after a myocardial infarction that required veno-arterial extra corporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) support which was transeptally converted to left atrium veno-arterial (LAVA)-ECMO that then functioned as a temporary paracorporeal LVAD. This solution resolved left ventricular distension and served as a bridge-to-transplant.

- Citation: Lamastra R, Abbott DM, Degani A, Pellegrini C, Veronesi R, Pelenghi S, Dezza C, Gazzaniga G, Belliato M. Left atrium veno-arterial extra corporeal membrane oxygenation as temporary mechanical support for cardiogenic shock: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(27): 6531-6536

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i27/6531.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i27.6531

Cardiogenic shock (CS) is a common cause of mortality and management remains challenging despite advances in therapeutic options. CS complicates 5% to 10% of cases of acute myocardial infarction and is the leading cause of death after myocardial infarction[1]. When vasopressor and inotropic support are not enough, the next step is often mechanical circulatory support such as intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), ImpellaTM, veno-arterial extra corporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO), and others. When VA-ECMO is chosen, left ventricular (LV) distension with subsequent worsening of LV failure can become a major complication that requires LV unloading. Conservative management that includes optimizing volume status, adding inotropic agents and down-titration of VA-ECMO flow may resolve the LV distension. If conservative measures fail, IABP, ImpellaTM, percutaneous left ventricular assist devices (pLVAD) and transeptal cannulation (such as Tandem HeartTM) are invasive methods for reducing LV distension[2-4]. In this case report, a patient with CS after a myocardial infarction is placed on VA-ECMO with subsequent LV distension which we manage to resolve by modifying the VA-ECMO into a configuration called left atrial veno-arterial ECMO (LAVA-ECMO), which unloads the left ventricle without the need of an additional percutaneous procedure. Subsequently, LAVA-ECMO was converted into an LVAD.

Once CS has been diagnosed, and treatment has reached the point where mechanical support seems necessary without the hope of de-escalation, the decision for long-term left ventricular assist devices (VAD) support, transplant or other surgical procedures is difficult. In recent years the use of VAD has evolved, and its uses have broadened. Bridge-to-decision (BTD) describes the temporary use of a VAD until decisions about more definitive therapy are made or until a thorough assessment of cardiac recovery is possible. Patients with insignificant cardiac function but good neurological status may eventually undergo heart transplantation by transitioning from BTD to bridge-to-transplant. Very few patients undergo heart transplant while being supported by a short-term VAD because of the lengthy wait time for a suitable donor, therefore one outcome of BTD is the transition to a long-term LVAD to wait for a transplant in an outpatient setting[5]. Our patient was suitable for heart transplant according to general criteria, including having an end-stage heart disease not remediable by other conservative measures and not having major contraindications (irreversible pulmonary hypertension, active systemic infections, active malignancy, cerebrovascular disease, irreversible dysfunction to other organs or inability to comply with medical treatment)[6].

A 65-year-old man had chest pain that radiated to his left and right arms. An ambulance was called and an electrocardiogram (ECG) showed anterolateral ischemia. The patient was thus brought to our emergency department.

The patient suffered from acute myocardial injury two weeks before this episode of cardiac arrest with coronary angiography showing a 90% stenosis of the circumflex artery. He underwent immediate percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty plus one stent on each of the following coronary arteries: left main, left anterior descending, and left circumflex. On day +9 after admission, he started dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) anticoagulation (acetylsalicylic acid + Ticagrelor) and was discharged from the hospital. At the same time, he was found to be positive for Coronavirus-19 on a nasal swab but was asymptomatic. On day +12 he experienced a new ischemic episode (he was apparently uncompliant with the DAPT therapy due to Ticagrelor unavailability). He returned to the emergency department with an ECG showing an anterolateral ischemia.

No previous history of angina symptoms from cardiac disease.

No personal or family history of cardiac disease.

The patient was brought to the emergency department by ambulance with chest pain that radiated to the left and right arm. Upon arrival, the patient was awake but immediately went into cardiac arrest with an ECG showing ventricular fibrillation.

During the patient’s stay in the intensive care unit, the most important laboratory exams ordered included those relating to the ECMO configuration and complications.

Free hemoglobin, D-Dimer and Antithrombin III were all requested daily. Platelet count was closely monitored as it reduced progressively due to the extracorporeal circuit. Other complications included bleeding and sepsis. Anticoagulation was constantly monitored through activated coagulation time (every 2 h) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) twice daily. Pneumonia was also diagnosed through bacterial cultures.

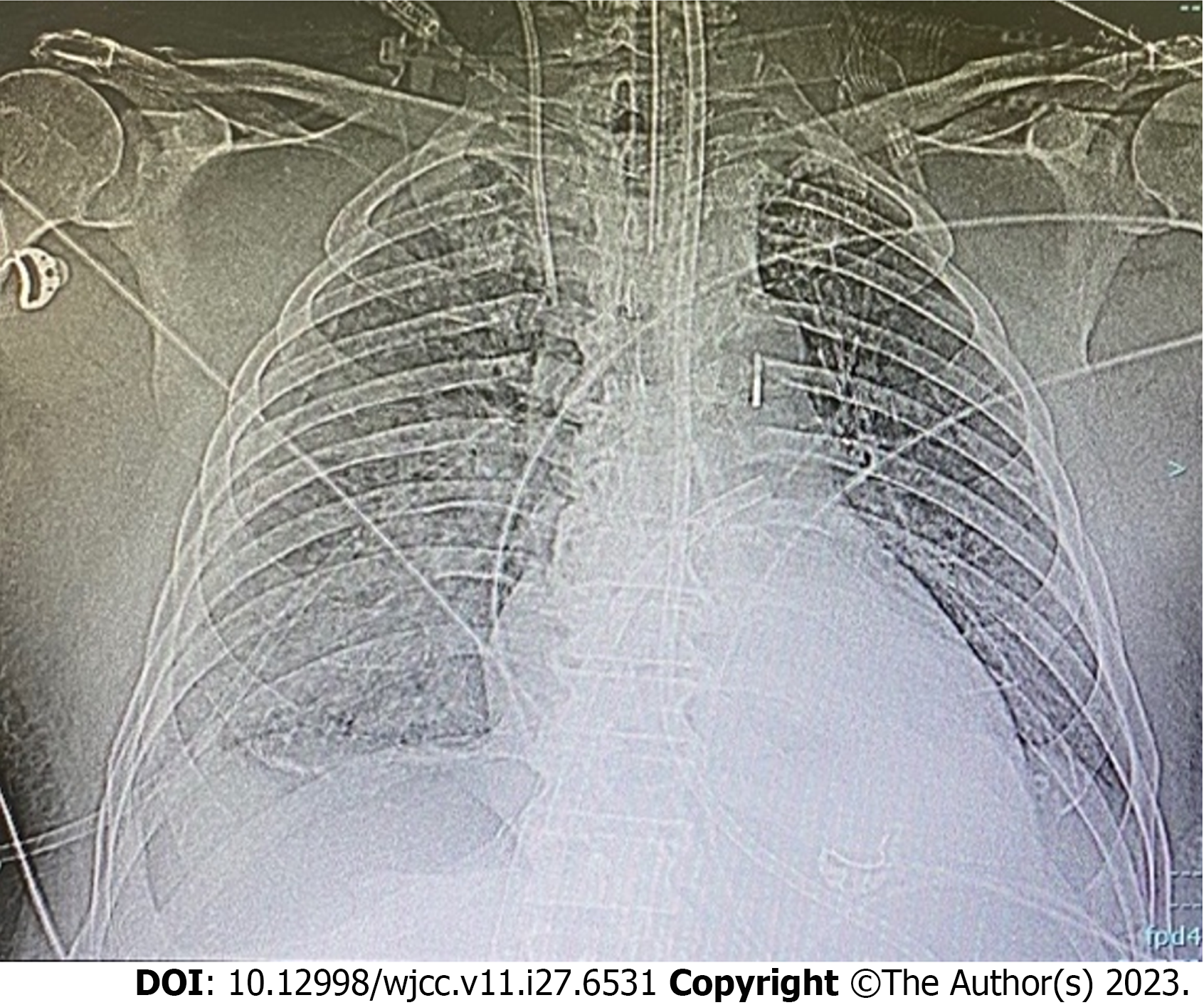

Imaging procedures included ultrasound, X-ray imaging and computerized tomography. An X-ray after LAVA-ECMO placement is shown in Figure 1.

Acute myocardial injury led to LV dysfunction. Other complications included bleeding and sepsis.

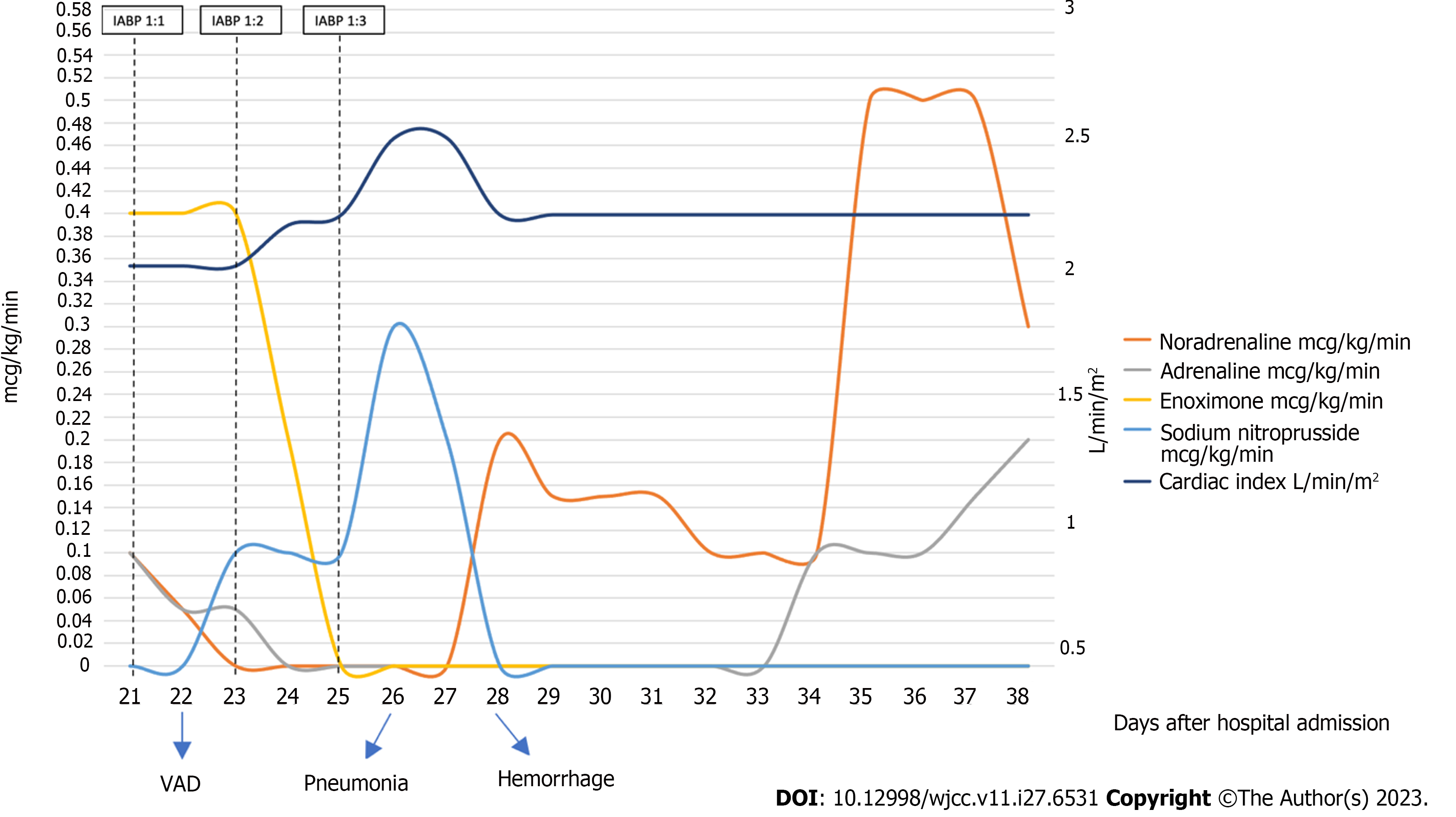

In our emergency department the patient underwent a cardiac arrest that did not respond to standard advanced cardiac life support, so he received femoro-femoral VA-ECMO support (ECMOLIFE, Eurosets S.r.l., Medolla (MO), Italy; HLS venous cannula 23 Fr and HLS arterial cannula 19 Fr, Getinge, Germany). He then underwent a second coronary angiography with stent placement on the same vessels and placement of an IABP (CARDIOSAVE hybrid, Maquet Getinge Group, Germany) with 1:1 ratio assistance. Afterwards, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and a trans-esophageal echocardiography (TEE) was performed with the following findings: severe LV dysfunction with interventricular septum hypokinesia, left atrial smoke, minimal aortic valve opening with mild aortic insufficiency, and severe reduction of right ventricle longitudinal and concentric function. The IABP was ineffective in unloading the left heart so, on day +20, a transeptal left atrial cannulation was performed and VA-ECMO was converted to Left Atrial Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (LAVA-ECMO, with Protek-Solo 21Fr, Livanova, United States) (Figure 1). TEE demonstrated improvement in the movement of the right ventricle, anterior septum and posterior wall with a persistent severe left ventricular dysfunction. On day +21 the patient underwent a cycle of Levosimendan infusion. Because of the permanent LV dysfunction and overdistension, on day +22, he was transferred to the cardiothoracic ICU. After progressive weaning from VA-ECMO with a reduction of venous return on the ECMO device (via a Hoffmann clamp on the systemic venous branch of the tube), the patient was definitively shifted to a total left ventricular assistance. The oxygenator was removed from the circuit, making an LVAD. Vasopressor and inotropic support were decreased as cardiac function improved (Figure 2). Platelet count reduced progressively due to the extracorporeal circuit. Other complications included bleeding and sepsis. Anticoagulation was constantly monitored through activated coagulation time (every 2 h) and aPTT twice daily. Despite such monitoring, the patient experienced multiple bleeding episodes, first at the cannula insertion sites and then in the airway. We managed bleeding through blood transfusions (4 units of packed red blood cells) and strict monitoring of coagulation markers. Pneumonia was also diagnosed, and antibiotics were started. Regular fibro-bronchoscopies were also done with the aim of maintaining adequate ventilation, removing clots, and clearing secretions. Renal failure (stage 3) developed, requiring continuous renal replacement therapy.

Our patient passed away on day +39 due to an uncontrolled airway bleed, 27 d after VA-ECMO initiation.

VA-ECMO support is commonly complicated with LV distension in patients with cardiogenic shock. We resolved this problem by transseptally converting VA-ECMO to LAVA- ECMO that also functioned as a temporary paracorporeal left ventricular assist device and resolved LV distension.

Physiologically, the venous drainage cannula which passes through the inter-atrial septum and into the left atrium reduces the left ventricular end diastolic volume and pressure, helping to reduce preload as well as left ventricular distension. The volume removed from the drainage cannula is added to the ejection fraction of the left heart through the arterial cannula, thus improving tissue perfusion.

ECMO requires the blood to be continuously anti-coagulated, which poses a constant risk for hemorrhagic complications. In addition, prolonged ICU admissions increase the likelihood of septic complications. To our knowledge, the LAVA-ECMO configuration does not seem to pose any additional risk of hemorrhage or sepsis, in comparison to the normal VA or VV-ECMO. No specific studies have been designed to evaluate this comparison.

This clinical case demonstrated that LAVA-ECMO is a viable strategy to unload the LV without another invasive percutaneous or surgical procedure. We demonstrate the ability to use LAVA-ECMO and the ability for its conversion to an LVAD system, as has been demonstrated in the literature[4,7]. One downside is that LAVA-ECMO requires a transeptal percutaneous cannulation that, when removed, could result in a small, residual, atrial septal defect, that could be repaired through a minimally invasive procedure. A benefit of this technique is that the procedure is potentially reversible, should the patient require VA-ECMO support again. A transeptal LV venting approach like LAVA-ECMO may be indicated over ImpellaTM in cases where less LV unloading is required and where a restrictive myocardium could cause LV suctioning[4]. Left ventricular over-distention is a well-known complication of peripheral VA-ECMO in cardiogenic shock and LAVA-ECMO through transeptal cannulation offers an undervalued and safe approach for treating LV overloading, without the need of an additional percutaneous access.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lakusic N, Croatia; Ong H, Malaysia S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Vahdatpour C, Collins D, Goldberg S. Cardiogenic Shock. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 43.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cevasco M, Takayama H, Ando M, Garan AR, Naka Y, Takeda K. Left ventricular distension and venting strategies for patients on venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:1676-1683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tavazzi G, Alviar CL, Colombo CNJ, Dammassa V, Price S, Vandenbriele C. How to unload the left ventricle during veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023;24:696-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lorusso R, Meani P, Raffa GM, Kowalewski M. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and left ventricular unloading: What is the evidence? JTCVS Tech. 2022;13:101-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Myers TJ. Temporary ventricular assist devices in the intensive care unit as a bridge to decision. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2012;23:55-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | de Jonge N, Kirkels JH, Klöpping C, Lahpor JR, Caliskan K, Maat AP, Brügemann J, Erasmus ME, Klautz RJ, Verwey HF, Oomen A, Peels CH, Golüke AE, Nicastia D, Koole MA, Balk AH. Guidelines for heart transplantation. Neth Heart J. 2008;16:79-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Phillip R, Howard J, Hawamdeh H, Tribble T, Gurley J, Saha S. Left Atrial Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Case Series: A Single-Center Experience. J Surg Res. 2023;281:238-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |