Published online Sep 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i27.6515

Peer-review started: May 31, 2023

First decision: July 17, 2023

Revised: August 6, 2023

Accepted: August 23, 2023

Article in press: August 23, 2023

Published online: September 26, 2023

Processing time: 112 Days and 8.9 Hours

Non-liquefied multiple liver abscesses (NMLA) can induce sepsis, septic shock, sepsis-associated kidney injury (SA-AKI), and multiple organ failure. The inability to perform ultrasound-guided puncture and drainage to eradicate the primary disease may allow for the persistence of bacterial endotoxins and endogenous cytokines, exacerbating organ damage, and potentially causing immunosuppression and T-cell exhaustion. Therefore, the search for additional effective treatments that complement antibiotic therapy is of great importance.

A 45-year-old critically ill female patient presented to our hospital’s intensive care unit with intermittent vomiting, diarrhea, and decreased urine output. The patient exhibited a temperature of 37.8 °C. Based on the results of liver ultrasonography, laboratory tests, fever, and oliguria, the patient was diagnosed with NMLA, sepsis, SA-AKI, and immunosuppression. We administered antibiotic therapy, entire care, continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) with an M100 hemo

Based on the entire therapeutic regimen, the early combination of CRRT and HP therapy may control sepsis caused by NMLA and help control infections, reduce inflammatory responses, and improve CD8+ T-cell immune function.

Core Tip: Non-liquefied multiple liver abscesses (NMLA) can lead to sepsis, septic shock, and sepsis-associated kidney injury (SA-AKI). Early treatment with continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) and hemoperfusion (HP) is particularly important when the patient is not a candidate for ultrasound-guided drainage or surgical intervention. The combination of CRRT and HP is used to control infections, reduce inflammation, and promote T-cell function. This case highlights the importance of holistic treatment in managing septic shock and SA-AKI caused by NMLA and the potential benefits of timely CRRT and HP therapy.

- Citation: Tang ZQ, Zhao DP, Dong AJ, Li HB. Blood purification for treatment of non-liquefied multiple liver abscesses and improvement of T-cell function: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(27): 6515-6522

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i27/6515.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i27.6515

Liver abscess (LA) is a common and acute disease that can be fatal. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that the incidence and mortality of LA are rising yearly[1]. The condition is triggered by various microorganisms that can spread via the arterial, venous, or biliary tract, or direct dissemination. Enteric gram-negative bacteria, including Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumonia, are the most commonly identified pathogens[2]. The clinical manifestations of LA are severe with high fever, right upper abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and jaundice. Moreover, LA frequently occurs in immunosuppressed patients. Failure to receive timely and effective treatment may lead to sepsis, septic shock, sepsis-associated acute kidney injury (SA-AKI), and multi-organ failure[3]. Sung et al[4] demonstrated that the overall incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) was 1.51 times higher in an LA cohort than in a non-LA cohort. Therefore, controlling infections earlier, reducing the inflammatory response, regulating immune function, and protecting kidney function in LA-induced sepsis due to LA is particularly important.

Treatments for single or multiple LAs typically involve ultrasound-guided puncture and drainage or needle aspiration[5,6]. However, these measures may not be effective for multiple non-liquefied LA (NMLA), highlighting the need for safe and effective alternative treatment approaches. Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) plays a vital role in sepsis treatment by removing small- and medium-sized molecules through a convective action. However, CRRT is ineffective in removing large molecules such as lipopolysaccharides and protein-rich mediators. Hemoperfusion (HP) can overcome the aforementioned limitations and effectively remove large molecules. Therefore, the combination of CRRT and HP may yield a synergistic effect with high adsorption capacity and improved clinical outcomes. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of CRRT combined with HP for the treatment of septic shock and SA-AKI caused by NMLA.

A 49-year-old female patient was admitted to the hospital with nausea and vomiting for 2 d, accompanied by intermittent fever.

Two days before admission, the patient complained of unexplained nausea and vomiting, accompanied by fever with a peak temperature of 38.4 °C. Additionally, the patient experienced diarrhea with watery stools at least twice daily. The day before admission, the patient’s condition had deteriorated, resulting in oliguria and apathy. After undergoing a blood culture and other related tests at a local hospital, the patient was transferred to our hospital for further treatment. She was diagnosed with diarrhea in the emergency department and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). During the course of the disease, the patient had poor appetite and sleep and lost 5 kg of total body weight.

The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Although the patient received oral metformin to control her blood sugar levels, the effect was unsatisfactory.

The patient had no special personal or family history.

The patient was in a coma with involuntary movements upon admission and had the following vitals: Temperature: 37.8 °C, heart rate: 130 beats/min, respiration: 28 breaths/min, and blood pressure: 70/50 mmHg. The patient's bowel sounds were 6 beats/min, and the urine output was less than 0.5 mL/kg/min. No swelling of either lower limb was observed, and the Babinski sign was negative.

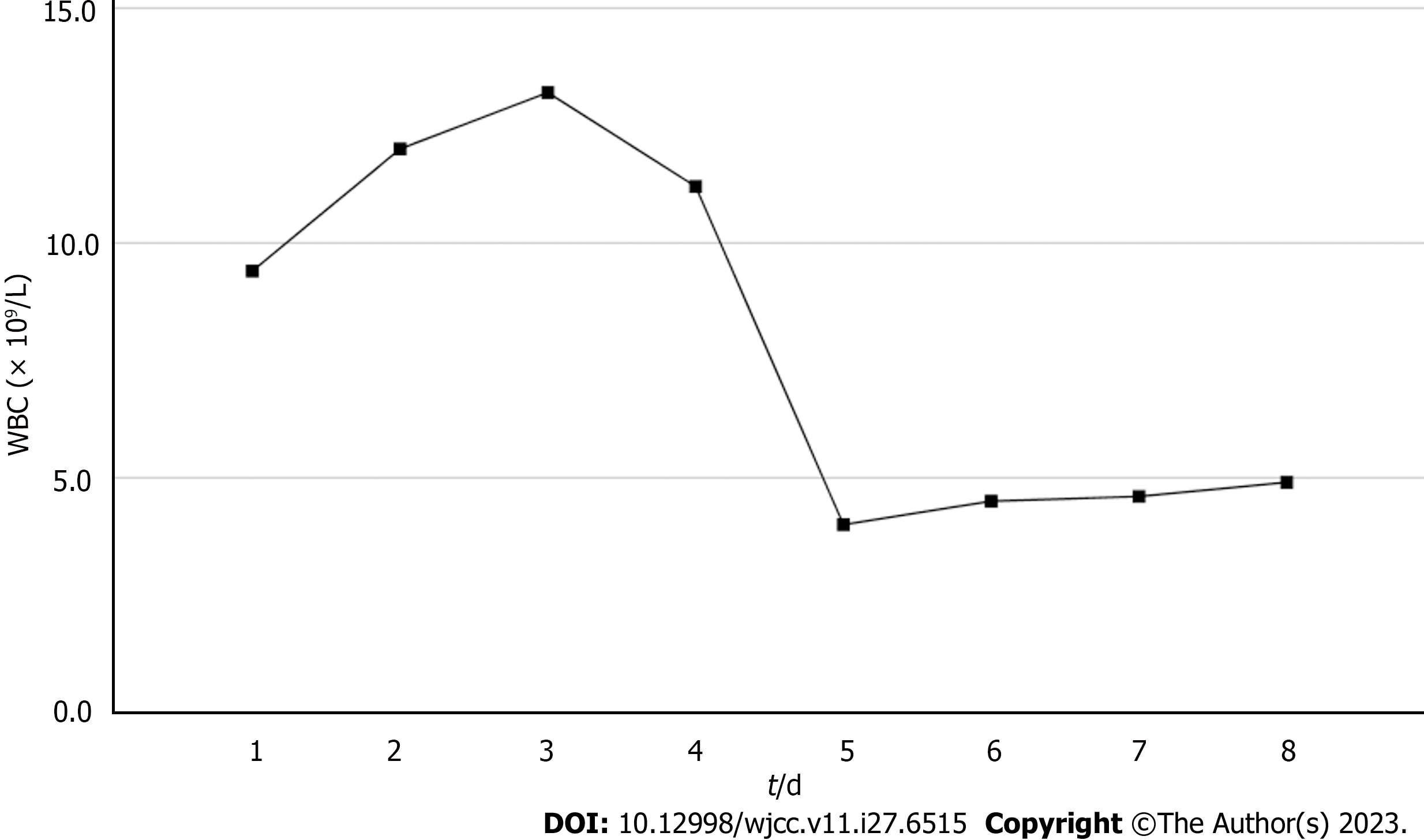

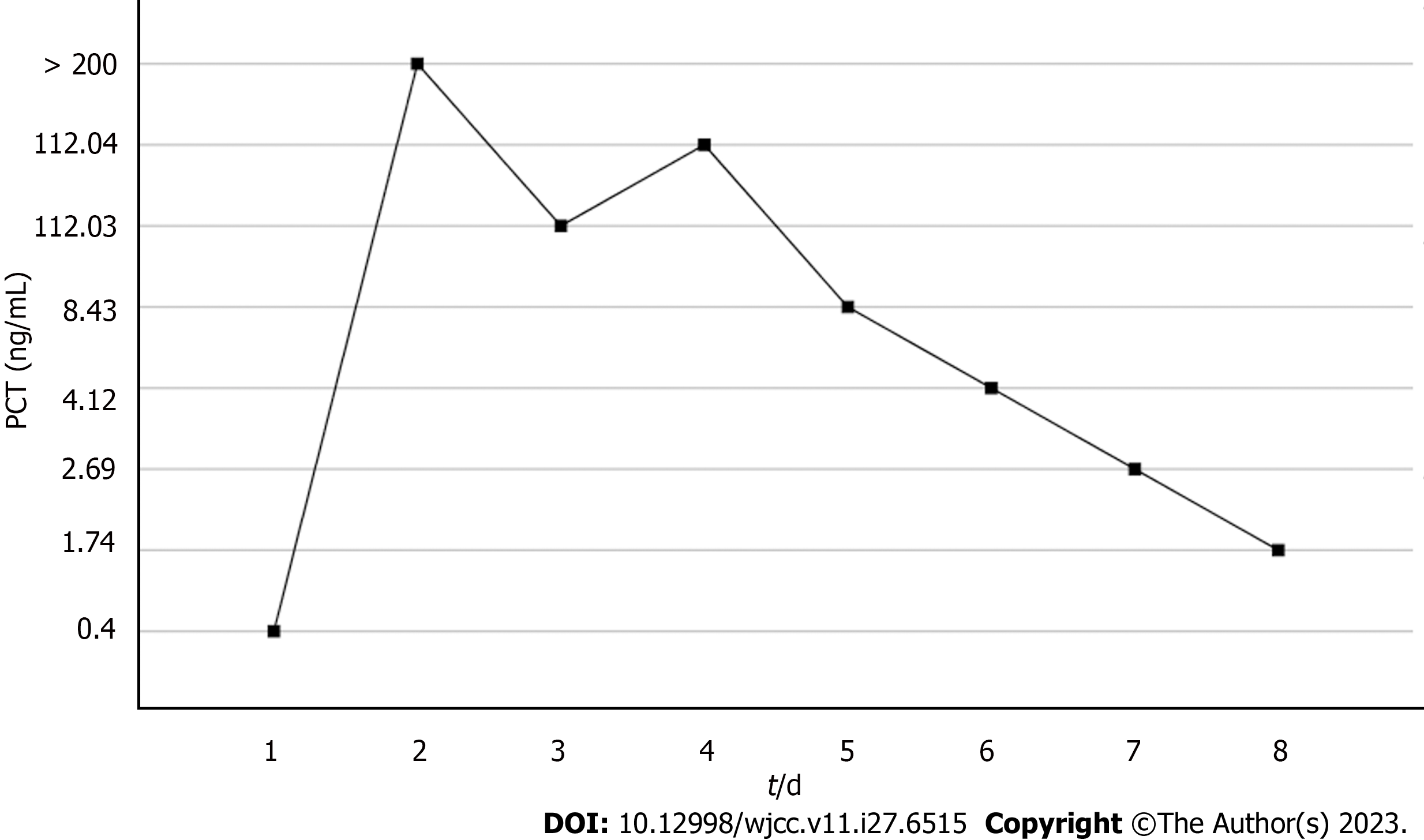

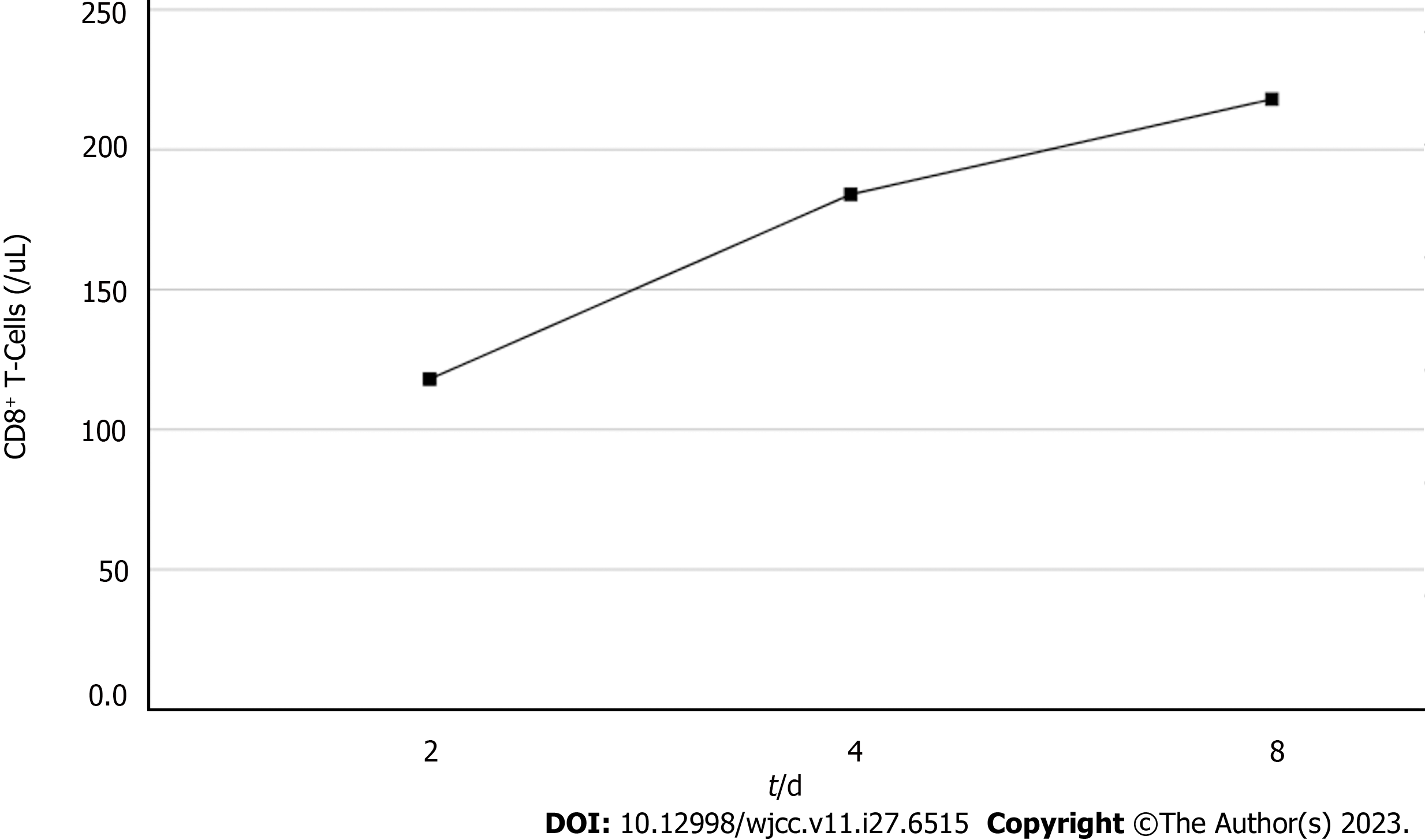

Upon admission, the white blood cells (WBC) were 9.4 × 109/L, and neutral granulocytes accounted for 94.5%. The platelet count was 5.2 × 1010/L, and procalcitonin (PCT) was 0.4 ng/mL. T-cell subpopulation analysis exhibited a significant reduction and exhaustion in both clusters of differentiated 4+ (CD4+) and cluster of differentiated 8+ (CD8+) T-cells. The CD4+ T-cell count was 4.4 × 1011/L, with 13.89% expressing the inhibitory receptor programmed death-1 (PD-1) on their surface, while the CD8+ T-cell count was 1.18 × 1011/L, with 26.65% expressing PD-1.

The patient had liver damage, with aspartate aminotransferase 923 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 410 U/L, and total bilirubin 27.6 µmol/L. The serum creatinine (SCr) was 380 µmol/L.

She had metabolic acidosis and was in a state of respiratory alkalosis, with a blood gas pH of 7.46, partial pressure of carbon dioxide of 25 mmHg, bicarbonate level of 17.8 mmol/L, base excess, -5.0 mmol/L, and lactate level, 1.2 mmol/L. The lactate level of the patient increased to 2.9 mmol/L after 24 h.

The liver ultrasound displayed multiple mixed-density shadows in the liver.

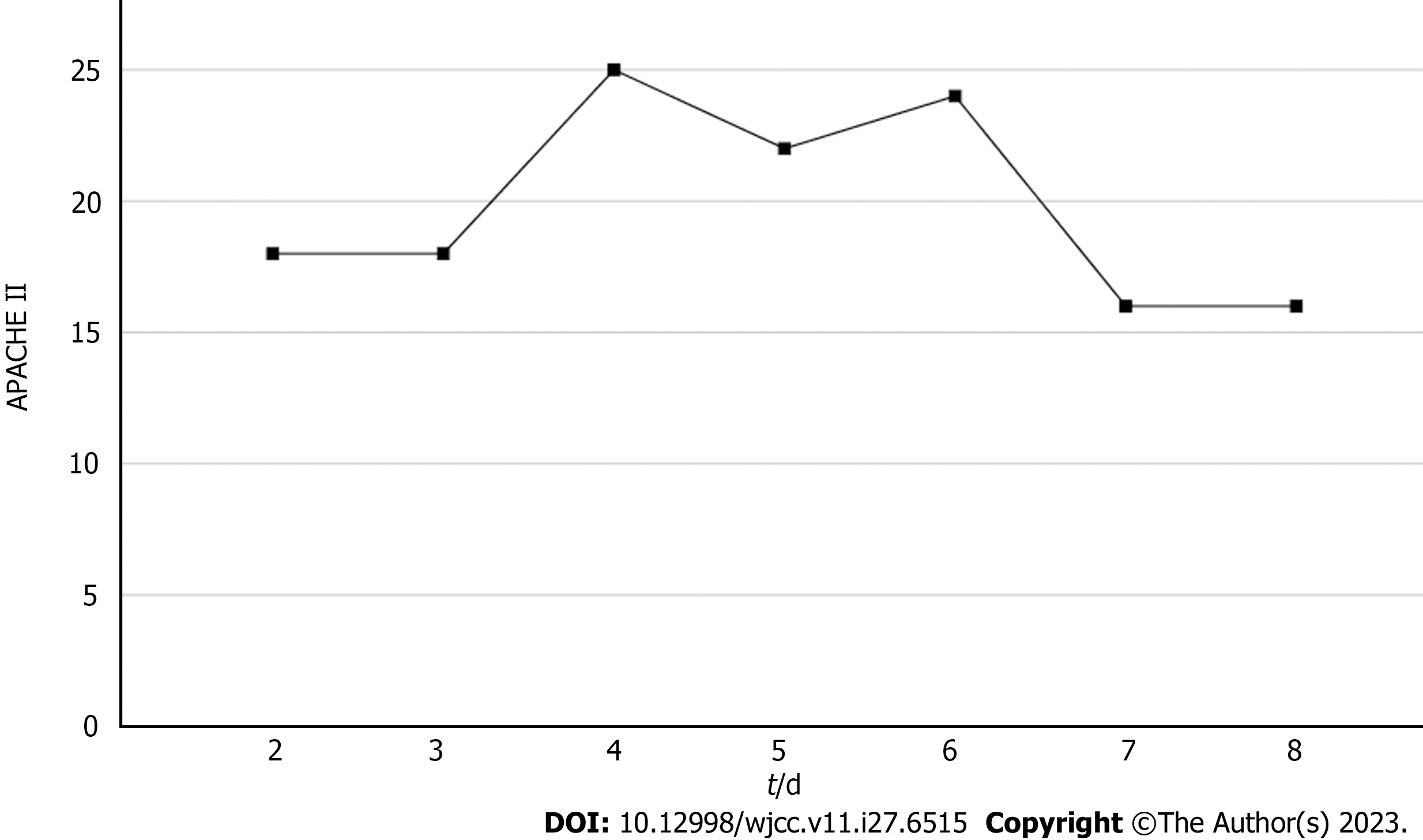

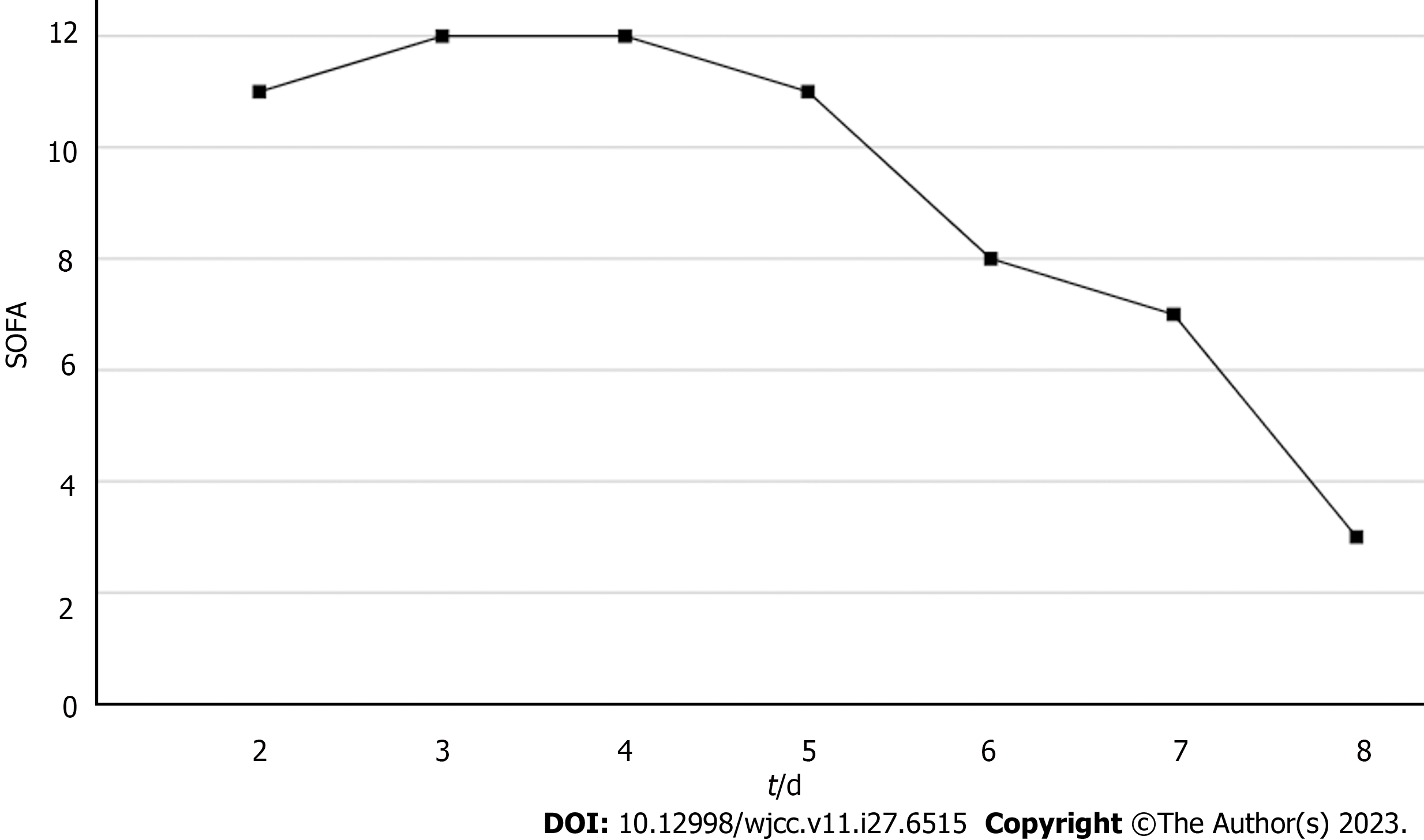

Based on the patient's chief complaint, history, physical examination, and supplementary examination, the patient was diagnosed with NMLA, sepsis, septic encephalopathy, septic shock, SA-AKI, and secondary immune deficiency. Her Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) score was 18, and her Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score was 11.

On the 1st day of admission, the empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic cefoperazone-sulbactam was initiated within 1 h, and fluid resuscitation for sepsis was performed within 3 h with 30 mL/kg of crystalloid solution. The blood pressure increased to 80/55 mmHg. We subsequently administered noradrenaline to achieve a mean arterial pressure of 65 mmHg and upgraded the antibiotics to imipenem and linezolid. The patient's urine gradually increased to 1.5–2.0 mL/kg/min. A glutathione injection was also administered. As the LA was not liquefied, ultrasound-guided puncture and drainage could not be performed.

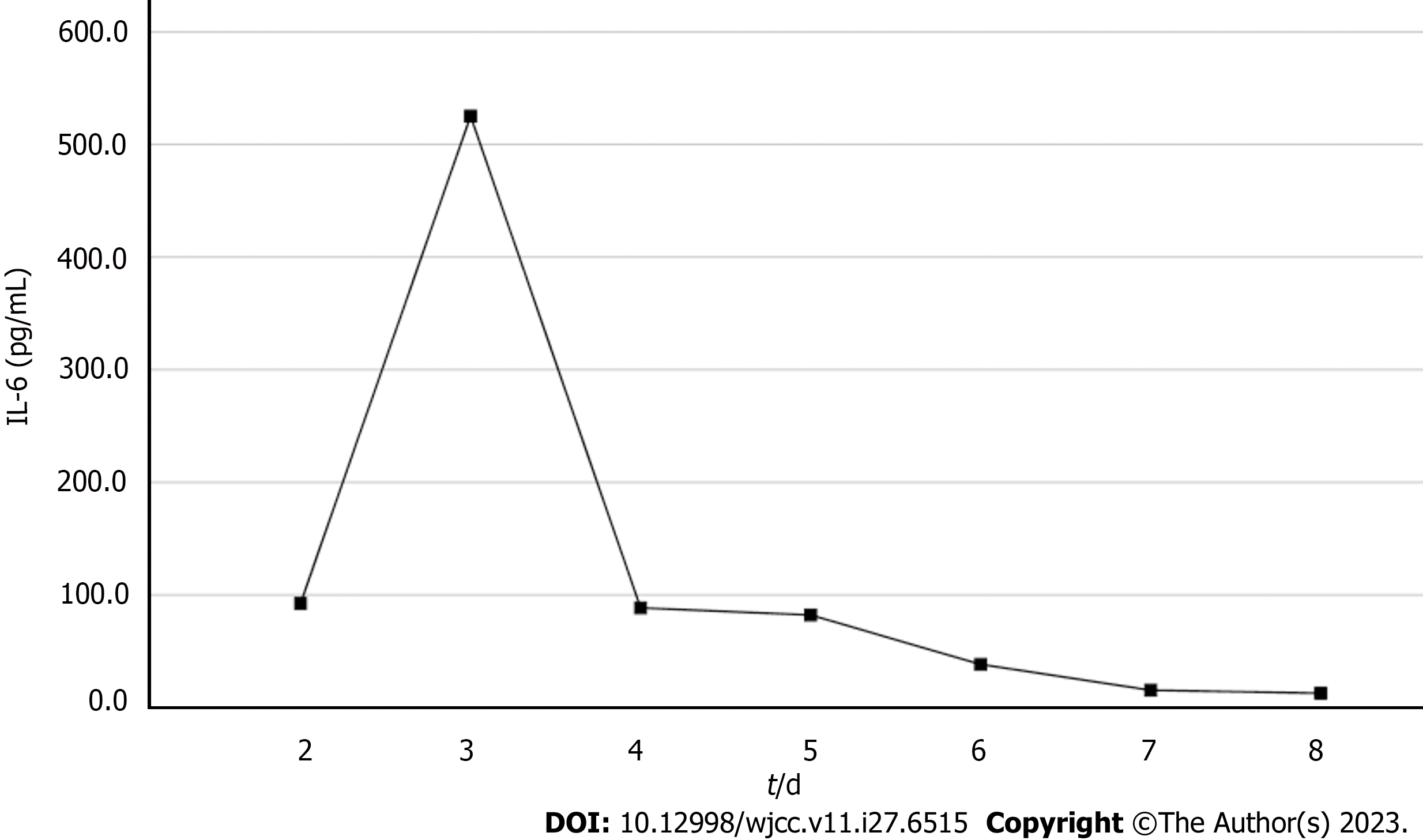

On the 2nd day, computed tomography of the liver confirmed the presence of NMLA. Sepsis was not adequately controlled and the lactate rose to 2.9 mmol/L. On the 3rd day, the WBC increased from 9.4 × 109/L to 1.2 × 1010/L, PCT increased from 0.4 ng/mL to 200 ng/mL and interleukin-6 (IL-6) was 92.5 µmol/L. Kidney function deteriorated and SCr levels increased from 380 to 403 mol/L. We proposed performing CRRT combined with HP therapy; however, the patient’s family refused the treatment owing to economic considerations. Liver ultrasonography displayed that the LA was still not liquefied, and puncture drainage could not be performed. At this point, the WBC rose to 1.32 × 1010/L and the IL-6 from 92.5 to 525.2 µmol/L abruptly. Blood culture results from a local hospital indicated a high likelihood of a gram-negative bacterial infection. The patient's urine output was maintained at 2 mL/kg/h with fluid resuscitation and norepinephrine. The SCr rose to 490 µmol/L. The patient developed septic shock and senescence-associated acute SA-AKI. Finally, a combination of CRRT and HP was performed on the 3rd day. A machine (PrismaFlex system) and filter (M100, Baxter), which were replaced every 24 h, were used for CRRT. The CRRT mode was continuous venovenous hemofiltration at 30 mL/kg/h and a blood flow rate of 120 mL/h. An HA380 membrane filter (Jafron Biomedical Co.) was used for HP once daily for 6 h. No adverse effects were observed throughout the treatment period. The continuous blood purification therapy was terminated on the 7th day. The anti-infection and other treatments were continued.

Based on the overall care and treatment, an improvement was observed during the 5-day CRRT in conjunction with HP treatment. After 48 h of CRRT and HP therapy, the WBC decreased from 1.32 × 1010/L to 4.0 × 109/L (Figure 1), and PCT decreased from 112.03 ng/mL to 8.43 ng/mL (Figure 2). Significant decreases in inflammatory parameters were observed, with IL-6 decreasing from 525.2 to 82.2 (Figure 3). Tissue perfusion significantly improved 5 d later, as evidenced by a decrease in lactate from 2.9 mmol/L to 0.9 mmol/L. Renal function gradually improved, and SCr levels decreased from 490 µmol/L to 129 µmol/L. Immune function improved, and the number of CD8+ T-cells rose from 5.56 × 1011/L to 6.71 × 1011/L (Figure 4). Although the LA remained liquefied and could not be drained, the patient was relieved with the APACHE II lowered to 16 (Figure 5), and the SOFA score declined to 3 (Figure 6). The patient was treated in the ICU for 10 d and then transferred to the gastroenterology department. The patient was discharged on the 21st day. The patient recovered after 28 d of follow-up.

LA is a common disease and a major cause of septic shock in the ICU[3]. Despite good care, the mortality rate of LA is 11%–14%[7]. Sepsis can lead to multiple organ damage, including AKI. Bagshaw et al[8] reported that patients with SA-AKI had an increased risk of death and a longer hospital stay than those without SA-AKI. Patients with liquefied LAs can be cured using ultrasound-guided puncture and drainage combined with antibiotic therapy, whereas NMLA can be considered for surgical treatment[9]. The patient’s condition was so severe that anesthesia was difficult to administer. Xu et al[10] applied ultrasound-guided percutaneous intrahepatic portal vein catheter injection of antibiotics to treat NMLA and achieved desirable results. However, the patient was unable to continue with the treatment because of septic encephalopathy. Therefore, to identify safe and effective treatment options for the patient was crucial.

The patient’s CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells were significantly below normal levels and expressed a large number of PD-1 inhibitory receptors. This indicated that the patient had T-cell exhaustion and was in an immunosuppressive state[11]. Platelet count is an important indicator of disease severity[12]. The patient's platelet count was as low as 5.2 × 1010/L. Gram-negative bacilli were highly suspected in the blood culture at the local hospital; nevertheless, no genus-specific or drug-sensitivity results were obtained. Gram-negative bacilli constantly release endotoxins and inflammatory mediators, leading to multiple organ damage[8]. Despite the administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics and fluid resuscitation during the first 2 d of admission, the patient's condition was not controlled. The SOFA score increased from 11 on admission to 12 on day 3. Additionally, NMLA cannot be treated with puncture drainage or surgery. Irritability caused by septic encephalopathy makes ultrasound-guided transportal antibiotic infusions a significant obstacle. Therefore, CRRT combined with HP might be a better alternative. Vardanjani et al[13] identified that a combination of CRRT and HP was a more effective method for treating patients of coronavirus disease 2019 and could prevent complications, such as AKI and septic shock. The patient was treated with CRRT and HP.

After 5-day CRRT combined with HP treatment, we established that the treatment lowered the severity of the disease, with a reduction in the SOFA score from 12 to 3 (Figure 6). Additionally, the levels of infection indicators, including the WBC count (Figure 1) and PCT (Figure 2), were significantly reduced. The platelet count gradually rebounded to 1.91 × 1011/L. Furthermore, the treatment was effective in controlling inflammatory responses such as IL-6 (Figure 3). Furthermore, vital signs gradually stabilized, and lactate levels decreased significantly. The findings confirm the value of CRRT combined with HP as a practical option for managing NMLA that cannot be treated through ultrasound-guided puncture drainage or surgery. Moreover, the treatment enhanced immune function by promoting CD8+ T-cell proliferation, although the underlying mechanism remains unclear. Moreover, IL-6 blocks the activation of CD8+ T-cells and inhibits their proliferation. When CRRT and HP eliminate IL-6, T-lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation are indirectly promoted. By contrast, IL-6 stimulates CD8+ T-cells to express the inhibitory receptor PD-1, leading to T-cell exhaustion[14]. Therefore, reducing IL-6 via this treatment may reduce PD-1 expression levels and T-cell exhaustion, ultimately resulting in enhanced immunity and cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell function for pathogen elimination. However, the exact underlying mechanism requires further investigation. Although hemofilter such as oXiris®[15] and polymyxin B-immobilized fiber columns (PMX)[16] are currently available for the treatment of sepsis, their high-cost constraints their clinical application to some extent. In contrast, the combination of the M100 and HA380 filters can significantly reduce the financial burden of sepsis management.

Based on care and treatment, a combination of CRRT and HP may contribute to infection control, clear inflammatory mediators, enhance CD8+ T-cell proliferation, and potentially alleviate CD8+ T-cell exhaustion. However, this study has several limitations. First, endotoxins were not monitored because they were not routine clinical laboratory tests. Second, due to economic constraints, a combination of CRRT and HP therapy was initiated on the 3rd day. The patient's condition would have been better if treated earlier using this method.

CRRT combined with HP may represent an effective therapeutic alternative to conventional interventions such as ultrasound-guided puncture drainage, ultrasound-guided injection of antibiotics, and surgery for NMLA. In addition to care and treatment, this method may help control infections. It also reduces inflammatory mediators, promotes CD8+ T-cell proliferation, and restores T-cell function.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Leowattana W, Thailand; Shelat VG, Singapore S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Zhang S, Zhang X, Wu Q, Zheng X, Dong G, Fang R, Zhang Y, Cao J, Zhou T. Clinical, microbiological, and molecular epidemiological characteristics of Klebsiella pneumoniae-induced pyogenic liver abscess in southeastern China. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8:166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Meddings L, Myers RP, Hubbard J, Shaheen AA, Laupland KB, Dixon E, Coffin C, Kaplan GG. A population-based study of pyogenic liver abscesses in the United States: incidence, mortality, and temporal trends. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:117-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yun SE, Jeon DH, Kim MJ, Bae EJ, Cho HS, Chang SH, Park DJ. The incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of acute kidney injury in patients with pyogenic liver abscesses. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015;19:458-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sung CC, Lin CS, Lin SH, Lin CL, Jhang KM, Kao CH. Pyogenic Liver Abscess is Associated With Increased Risk of Acute Kidney Injury: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liu CH, Gervais DA, Hahn PF, Arellano RS, Uppot RN, Mueller PR. Percutaneous hepatic abscess drainage: do multiple abscesses or multiloculated abscesses preclude drainage or affect outcome? J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:1059-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bahloul M, Chaari A, Bouaziz-Khlaf N, Kallel H, Herguefi L, Chelly H, Ben Hamida C, Bouaziz M. Multiple pyogenic liver abscess. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2962-2963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shelat VG, Wang Q, Chia CL, Wang Z, Low JK, Woon WW. Patients with culture negative pyogenic liver abscess have the same outcomes compared to those with Klebsiella pneumoniae pyogenic liver abscess. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2016;15:504-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bagshaw SM, Uchino S, Bellomo R, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, Bouman C, Macedo E, Gibney N, Tolwani A, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Ronco C, Kellum JA; Beginning and Ending Supportive Therapy for the Kidney (BEST Kidney) Investigators. Septic acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: clinical characteristics and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:431-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 600] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Meister P, Irmer H, Paul A, Hoyer DP. Therapy of pyogenic liver abscess with a primarily unknown cause. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2022;407:2415-2422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Xu S, Wang Y, Chen J, Hu Y, Zhang Q, Chen G, Yu F. Application of ultrasound-guided percutaneous intrahepatic portal vein catheterization with antibiotic injection for treating unliquefied bacterial liver abscess. Hepatol Res. 2017;47:E187-E192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yan L, Chen Y, Han Y, Tong C. Role of CD8(+) T cell exhaustion in the progression and prognosis of acute respiratory distress syndrome induced by sepsis: a prospective observational study. BMC Emerg Med. 2022;22:182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schupp T, Weidner K, Rusnak J, Jawhar S, Forner J, Dulatahu F, Brück LM, Hoffmann U, Kittel M, Bertsch T, Akin I, Behnes M. Diagnostic and prognostic role of platelets in patients with sepsis and septic shock. Platelets. 2023;34:2131753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Esmaeili Vardanjani A, Ronco C, Rafiei H, Golitaleb M, Pishvaei MH, Mohammadi M. Early Hemoperfusion for Cytokine Removal May Contribute to Prevention of Intubation in Patients Infected with COVID-19. Blood Purif. 2021;50:257-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu W, Dietze KK, Gibbert K, Lang KS, Trilling M, Yan H, Wu J, Yang D, Lu M, Roggendorf M, Dittmer U, Liu J. TLR ligand induced IL-6 counter-regulates the anti-viral CD8(+) T cell response during an acute retrovirus infection. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li Y, Ji XJ, Jing DY, Huang ZH, Duan ML. Successful treatment of gastrointestinal infection-induced septic shock using the oXiris(®) hemofilter: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:8157-8163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ronco C, Klein DJ. Polymyxin B hemoperfusion: a mechanistic perspective. Crit Care. 2014;18:309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |