Published online Sep 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i27.6476

Peer-review started: March 31, 2023

First decision: July 3, 2023

Revised: July 16, 2023

Accepted: August 2, 2023

Article in press: August 2, 2023

Published online: September 26, 2023

Processing time: 173 Days and 10 Hours

An unusual case of acute acquired concomitant esotropia (AACE) with congenital paralytic strabismus in the right eye is reported.

A 23-year-old woman presented with complaints of binocular diplopia and esotropia of the right eye lasting 4 years and head tilt to the left since 1 year after birth. The Bielschowsky head tilt test showed right hypertropia on a right head tilt. She did not report any other intracranial pathology. A diagnosis of AACE and right congenital paralytic strabismus was made. Then, she underwent medial rectus muscle recession and lateral rectus muscle resection combined with inferior oblique muscle myectomy in the right eye. One day after surgery, the patient reported that she had no diplopia at either distance or near fixation and was found to be orthophoric in the primary position; furthermore, her head posture immediately and markedly improved.

In future clinical work, in cases of AACE combined with other types of strabis

Core Tip: Clinically, in cases of older children, adults, or even the elderly with sudden diplopia accompanied by simultaneous or subsequent esotropia, acute acquired concomitant esotropia (AACE) should be considered after excluding intracranial space-occupying lesions and vascular diseases. In recent years, the diagnosis and treatment of AACE have improved considerably, and until now no one has reported any case of AACE combined with other types of strabismus either in China or abroad. Here, we report one case of AACE with congenital paralytic strabismus.

- Citation: Zhang MD, Liu XY, Sun K, Qi SN, Xu CL. Acute acquired concomitant esotropia with congenital paralytic strabismus: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(27): 6476-6482

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i27/6476.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i27.6476

Acute acquired concomitant esotropia (AACE) is a relatively rare form of strabismus that occurs suddenly and is accompanied by diplopia that is more obvious at far distances than near ones. As early as 1958, Burian et al[1] summarized the types of AACE and reported five cases. In recent years, the excessive use of smartphones has resulted in an increasing number of people performing excessive amounts of near work. This became more pronounced during the coronavirus disease 2019 lockdown, during which the incidence of AACE significantly increased[2,3]. Despite this, no one has yet reported any case of AACE combined with other types of strabismus. We here share one case of AACE with congenital paralytic strabismus to enhance our understanding of the disease and to design the surgery used to treat it better.

A 23-year-old woman presented with complaints of binocular diplopia with esotropia of the right eye lasting 4 years with no readily discernable cause.

The patient used computers for more than 10 h a day prior to the onset of the symptoms described above. The diplopia was more obvious when the patient focused on distant objects and disappeared when she covered one eye.

The patient’s parents noticed that the patient tilted her head to see at 1 year of age, but they did not pay further attention to this behavior. At 3 years of age, the patient visited the hospital and was diagnosed with congenital superior oblique muscle palsy in her right eye, which was not treated.

There was no family history of similar diseases.

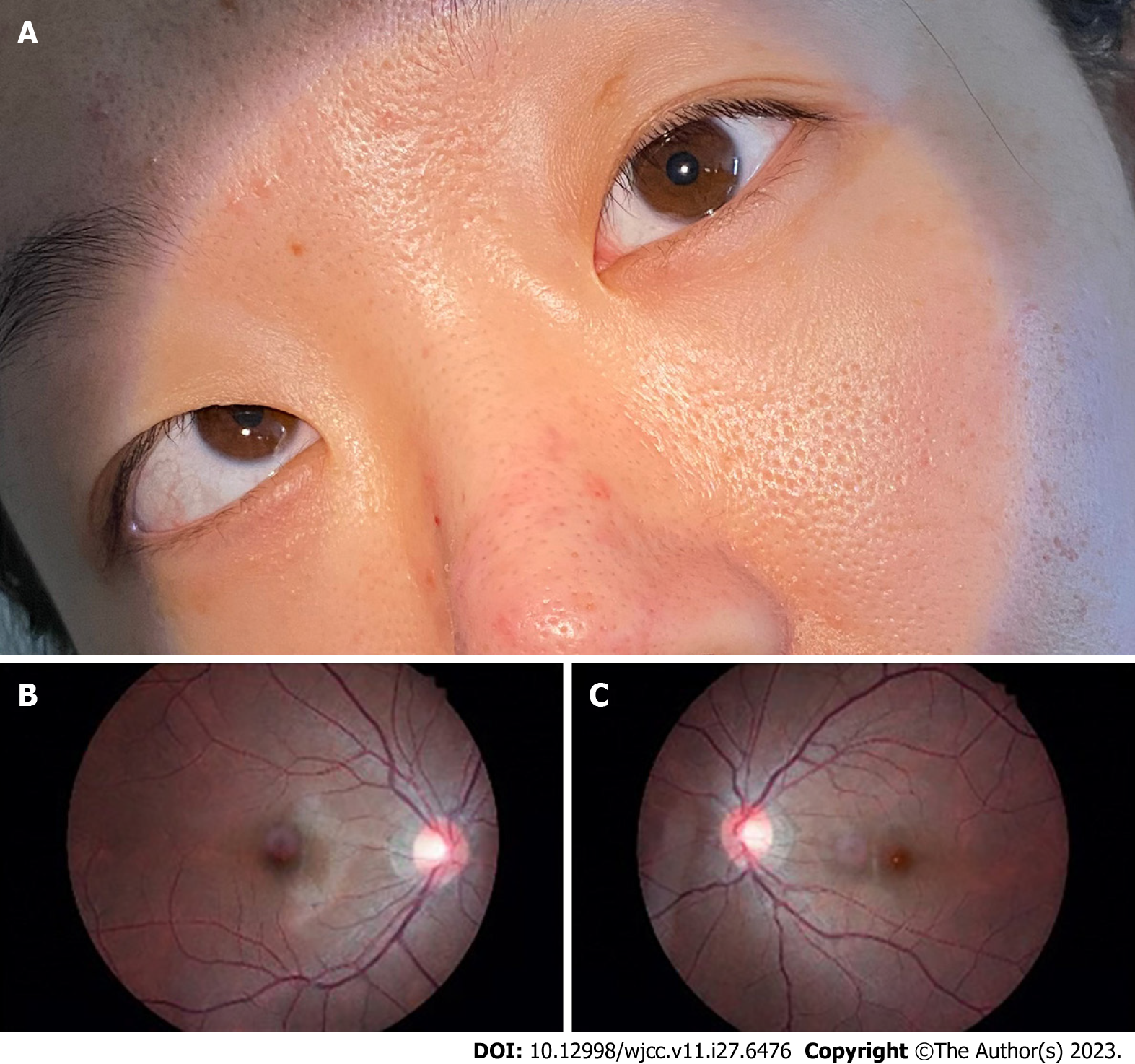

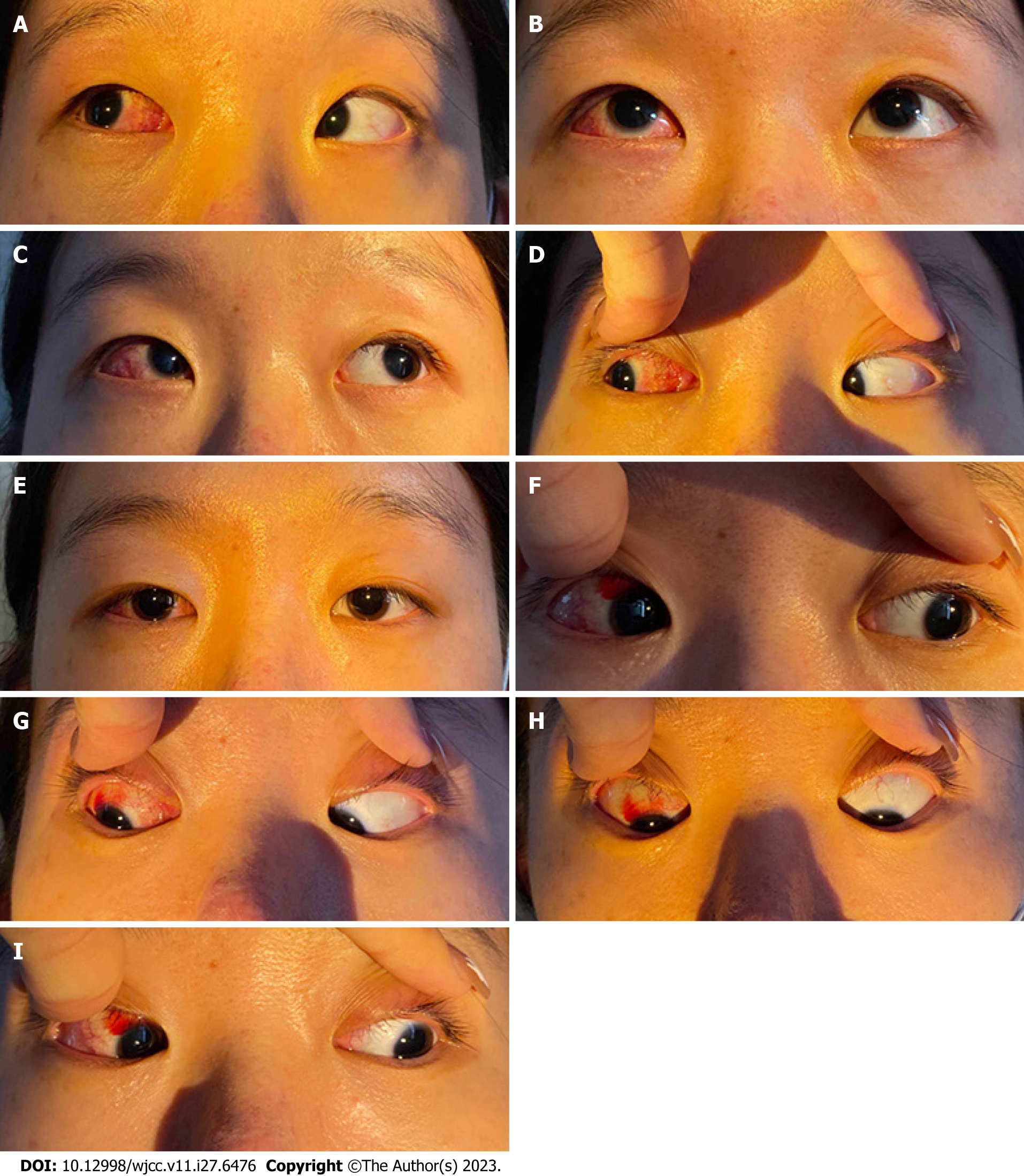

Ophthalmic examination showed that the patient’s uncorrected visual acuity was 20/125 in the right eye and that it was improving up to 20/20 (with −8.00D), while it was 20/200 in the left eye and was improving up to 20/20 (with −8.00D). Tonometry revealed intraocular pressures of 18 mmHg and 17 mmHg in the right and left eyes, respectively. Several eye position tests were then performed. The Hirschberg test showed 15° esotropia (ET) with 5° right hypertropia (RHT) for the right eye, while the prism and alternative cover test showed 60ΔET with 8ΔRHT at distance fixation (6 m) and 65ΔET with 8ΔRHT at near fixation (33 cm) on right gaze and 65ΔET with 8ΔRHT at distance fixation (6 m) and 70ΔET with 10ΔRHT at near fixation (33 cm) on left gaze. The patient had left head tilt (Figure 1). The eye movements showed an overaction of the inferior oblique muscle of +3 in the right eye (Figure 1F), an underaction of the superior oblique muscle of −1 (Figure 1I), and full movement in the left eye. On the Bielschowsky head tilt test, the patient showed right hypertropia worse with right head tilt (Figure 2A). Stereopsis was not detectable using the Titmus test. The Bagolini striated glasses test indicated suppression of the right eye at near fixation.

Not applicable.

Based on these examinations, we considered a diagnosis of AACE, right congenital paralytic strabismus, and binocular refractive error.

The patient underwent a medial rectus muscle recession of 5 mm and lateral rectus muscle resection of 6 mm combined with inferior oblique muscle myectomy in the right eye under anesthesia.

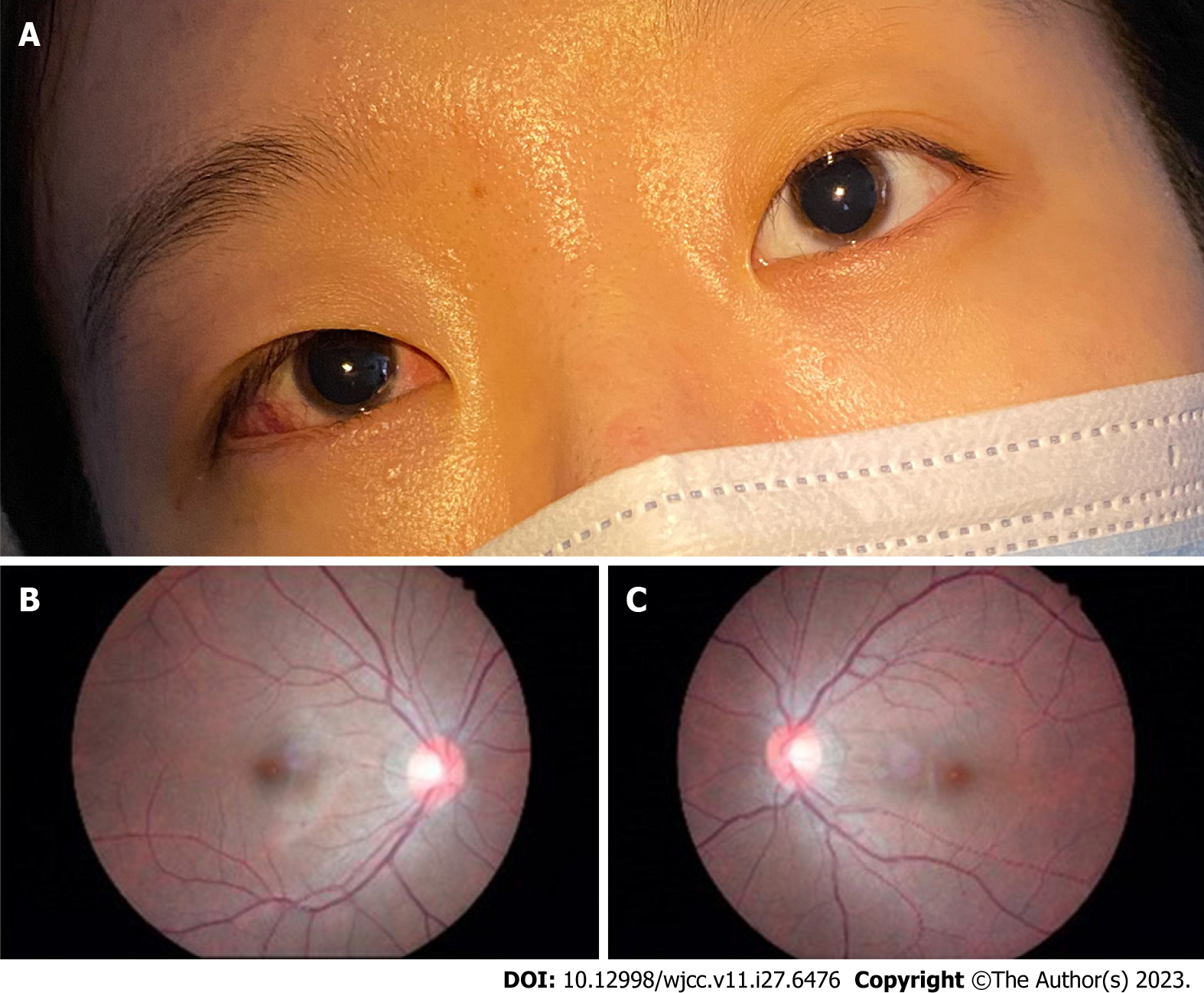

On the first day after surgery, the patient reported that she had no diplopia at distance or near fixation, and she was found to be orthophoric in the primary position by the corneal light reflex (Hirschberg) test, and the alternative cover test revealed a mild esophoria for both distance and near fixation. At the 1-week follow-up visit, the patient reported that her eyes were straight with no diplopia. The patient’s ductions and versions were full in all gaze positions, and her head posture markedly improved immediately after surgery (Figure 3). The Bielschowsky head tilt test showed a negative response (Figure 4A) and the fundus photography was still negative for ocular torsion (Figure 4B and C); however, judging from a comparison of pre- and post-operative measurements, her stereopsis was unchanged. Two months after surgery, the patient reported by email that she continued to experience excellent alignment with no diplopia. She also reported that she could perceive 3D movies stereoscopically. One year after surgery, the Titmus fly test results showed that the stereoacuity was 400 arc seconds.

Congenital superior oblique paralysis (SOP) is the most common type of congenital paralytic strabismus. It is characterized by superior oblique underaction and inferior oblique overaction. The hypertropia of the patient’s affected eye increased with healthy eye fixating and the Bielschowsky head tilt test was positive. Ocular examination of the patient revealed an underaction of the superior oblique muscle of −1 and an overaction of the inferior oblique muscle of +3 in the right eye. The right eye was higher than the left eye and the Bielschowsky head tilt test was positive, which supported our diagnosis. Patients with paralytic strabismus often adopt an abnormal head posture to maintain binocular vision and avoid diplopia. Paralysis of the superior oblique muscle causes the head to tilt away from the side of impairment, and this is the most common cause of ocular torticollis[4]. In this case, the patient consistently tilted her head to the left to ensure binocular single vision. The patient never sought medical attention for her SOP. In addition, subjective cyclotropia is usually absent in SOP patients, but objective excyclotropia may be found in the primary position using fundus photography. Although this patient had a history of SOP, fundus photography did not show excyclotropia. Clinically, we have found that a few patients have SOP, but their fundus photography is normal and without extorsion.

AACE is a relatively rare form of strabismus that occurs suddenly and is accompanied by diplopia that is more obvious at far distances than near ones. It is usually thought to be related to myopia[1], and excessive use of near vision may serve as a contributing risk factor for it[2]. However, the incidence of this eye disease has increased significantly in recent years. In this case, the patient reported diplopia that was more obvious at distance fixation, high myopia, and intense computer use for more than 10 h per day, all of which were consistent with the above clinical features. Some scholars believe that AACE may be related to intracranial pathology, but neurological and neuroradiological evaluations of the patient were negative, and no ophthalmic signs related to neurological involvement were observed[5,6].

The patient’s congenital SOP was accompanied by AACE in adulthood, and it did not cause obvious diplopia in childhood. Due to her compensatory head posture, the patient’s binocular visual function was guaranteed, but because of the onset of SOP prior to visual maturation, visual diplopia and confusion were absent. The AACE disrupted the original balance of the patient’s eyes, resulting in diplopia, but the compensatory head posture remained unchanged. In this case, the patient had been examined for stereopsis in another hospital when the progression of AACE reached 2 years. The Titmus fly test results showed that the stereoacuity was 400 arc seconds at near distances and was measurable at far distances. However, the patient had suffered total loss of stereopsis after four years of AACE. AACE is a progressive disease that gradually destroys binocular vision function as it continues. Over the past several years, some scholars have found there to be no significant effect of time elapsed from AACE onset to treatment with regard to stereopsis within half a year[7]. Conversely, patients who have suffered from AACE for more than half a year have notably impaired stereopsis. However, the recovery of stereopsis after treatment has nothing to do with the duration of AACE. Binocular vision function is established before the onset of AACE, which may be why the stereopsis of many adult patients with AACE returns to normal after surgical correction. One study found that stereopsis was fully recovered 2.2 ± 1.0 years after surgery[8]. In our case, the patient reported that she could perceive 3D movies stereoscopically, which was 2 mo after surgery, showing that she had regained gross stereopsis. At the 1-year follow-up visit, the patient’s stereoacuity improved to 400 arc seconds. However, no further recovery of stereopsis has yet been recorded; the patient’s recovery will be monitored in future follow-up visits.

In recent years, some studies have reported AACE combined with abducting nystagmus and orbital cellulitis[9,10]. However, there are no other reports of AACE combined with other types of strabismus, and both AACE and congenital SOP are relatively rare in clinical practice. We encountered this case and chose to resolve both types of strabismus at the same time. We performed a 5 mm recession of the medial rectus muscle and 6 mm resection of the lateral rectus muscle combined with inferior oblique muscle myectomy in the right eye. After the strabismus surgery, the diplopia disappeared immediately, and the patient was orthotropic at both distance and near fixation. The ductions and versions were full, and inferior oblique muscle weakening effectively solved vertical strabismus. The compensatory head posture was resolved, and the patient reported a high level of satisfaction. This is the first case report of AACE combined with congenital paralytic strabismus, and although it is not very innovative in terms of surgical approach, it has significant clinical significance.

This case suggests that although two types of strabismus may coexist, in terms of surgical design, it is possible to resolve both at the same time through conventional single strabismus surgery. The two strabismus surgeries do not interfere with each other and our patient experienced good results, proving that patients can recover from two types of strabismus simultaneously.

We would like to express our gratitude to Long-Yan Yang for their suggestions and instructions regarding the present report.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Ophthalmology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Yao J, China S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Burian HM, Miller JE. Comitant convergent strabismus with acute onset. Am J Ophthalmol. 1958;45:55-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lee HS, Park SW, Heo H. Acute acquired comitant esotropia related to excessive Smartphone use. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016;16:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vagge A, Giannaccare G, Scarinci F, Cacciamani A, Pellegrini M, Bernabei F, Scorcia V, Traverso CE, Bruzzichessi D. Acute Acquired Concomitant Esotropia From Excessive Application of Near Vision During the COVID-19 Lockdown. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2020;57:e88-e91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kushner BJ. Ocular causes of abnormal head postures. Ophthalmology. 1979;86:2115-2125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schreuders J, Thoe Schwartzenberg GW, Bos E, Versteegh FG. Acute-onset esotropia: should we look inside? J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2012;49 Online:e70-e72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hoyt CS, Good WV. Acute onset concomitant esotropia: when is it a sign of serious neurological disease? Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:498-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fu T, Wang J, Levin M, Xi P, Li D, Li J. Clinical features of acute acquired comitant esotropia in the Chinese populations. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e8528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Spierer A. Acute concomitant esotropia of adulthood. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1053-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kang KD, Kang SM, Yim HB. Acute acquired comitant esotropia after orbital cellulitis. J AAPOS. 2006;10:581-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lyons CJ, Tiffin PA, Oystreck D. Acute acquired comitant esotropia: a prospective study. Eye (Lond). 1999;13 (Pt 5):617-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |