Published online Sep 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i27.6440

Peer-review started: June 11, 2023

First decision: August 8, 2023

Revised: August 10, 2023

Accepted: August 29, 2023

Article in press: August 29, 2023

Published online: September 26, 2023

Processing time: 100 Days and 22 Hours

Diaphragmatic hernia (DH) is extremely rarely described during pregnancy. Due to the rarity, there is no diagnostic or treatment algorithm for DH in pregnancy.

To summarize and define the most appropriate diagnostic methods and therapeutic options for DH in pregnancy based on scarce literature.

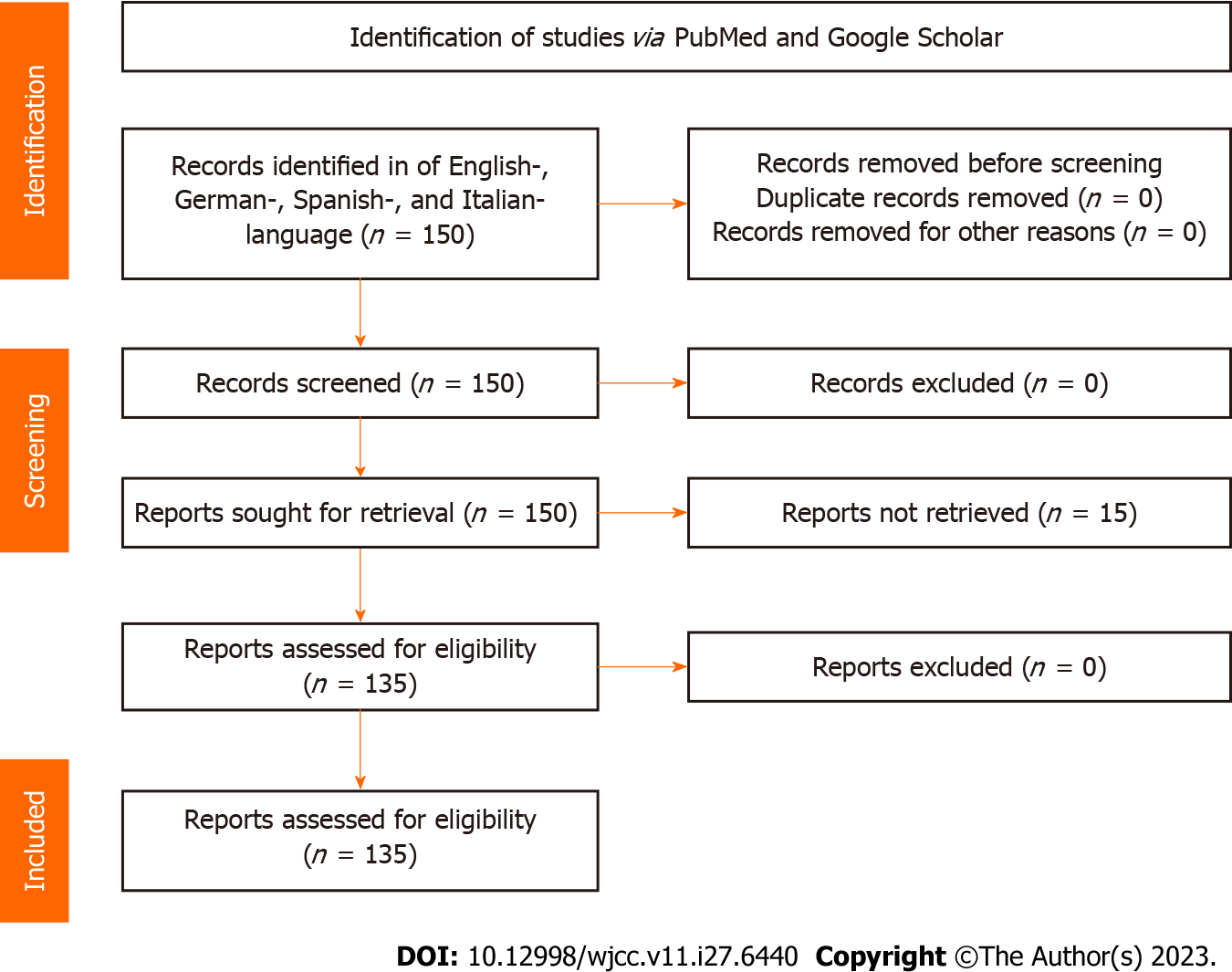

Literature search of English-, German-, Spanish-, and Italian-language articles were performed using PubMed (1946–2021), PubMed Central (1900–2021), and Google Scholar. The PRISMA protocol was followed. The search terms included: Maternal diaphragmatic hernia, congenital hernia, pregnancy, cardiovascular collapse, mediastinal shift, abdominal pain in pregnancy, hyperemesis, diaphragmatic rupture during labor, puerperium, hernie diaphragmatique maternelle, hernia diafragmática congenital. Additional studies were identified by reviewing reference lists of retrieved studies. Demographic, imaging, surgical, and obstetric data were obtained.

One hundred and fifty-eight cases were collected. The average maternal age increased across observed periods. The proportion of congenital hernias increased, while the other types appeared stationary. Most DHs were left-sided (83.8%). The median number of herniated organs declined across observed periods. A working diagnosis was correct in 50%. DH type did not correlate to maternal or neonatal outcomes. Laparoscopic access increased while thoracotomy varied across periods. Presentation of less than 3 days carried a significant risk of strangulation in pregnancy.

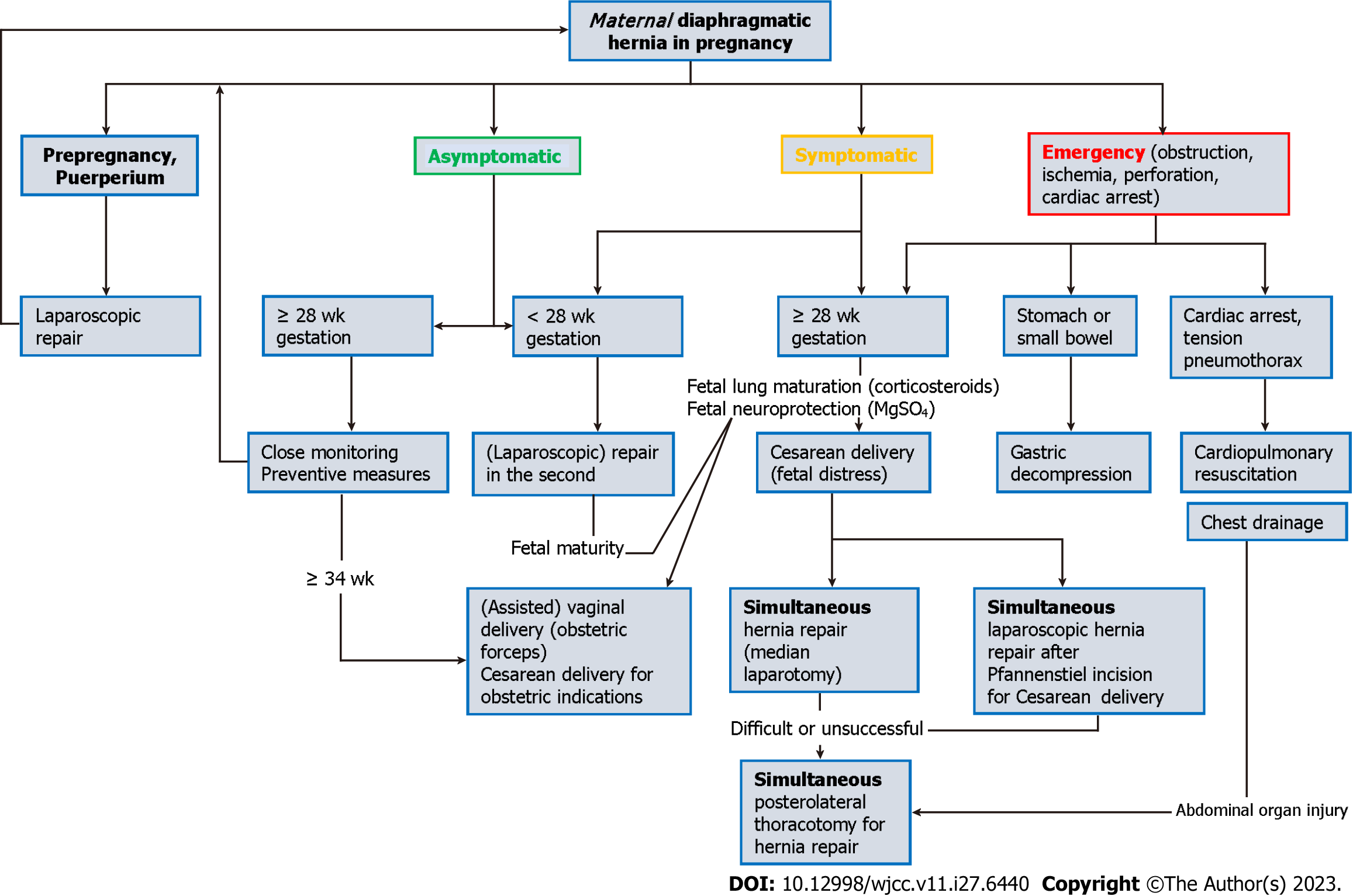

The clinical presentation of DH is easily confused with common chest conditions, delaying the diagnosis, and increasing maternal and fetal mortality. Symptomatic DH should be included in the differential diagnosis of pregnant women with abdominal pain associated with dyspnea and chest pain, especially when followed by collapse. Early diagnosis and immediate intervention lead to excellent maternal and fetal outcomes. A proposed algorithm helps manage pregnant women with maternal DH. Strangulated DH requires an emergent operation, while delivery should be based on obstetric indications.

Core Tip: Diaphragmatic hernias (DH) in pregnancy are extremely rare. The average maternal age and the proportion of congenital hernias increased. Most DHs were left-sided. The number of herniated organs declined. The clinical presentation is easily confused with common chest conditions, delaying the diagnosis, and increasing maternal and fetal mortality. A working diagnosis was correct in 50%. DH type did not correlate to maternal or neonatal outcomes. Laparoscopic access increased while thoracotomy varied. Presentation of less than 3 days carried a significant risk of strangulation in pregnancy. A proposed algorithm helps manage pregnant women with maternal DH. Strangulated DH requires an emergent operation, while delivery should be based on obstetric indications.

- Citation: Augustin G, Kovač D, Karadjole VS, Zajec V, Herman M, Hrabač P. Maternal diaphragmatic hernia in pregnancy: A systematic review with a treatment algorithm. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(27): 6440-6454

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i27/6440.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i27.6440

Diaphragmatic hernia (DH) is a congenital or acquired diaphragmatic defect resulting in a protrusion of abdominal contents into the thoracic cavity. DH is extremely rare during pregnancy. On average, a clinician deals with a single pregnant patient during a career. Walter Gray Crump made the first available report on the successful operative DH treatment at 3 mo gestation in 1911[1]. Robert Oscar Müller made one of the first descriptions of incarcerated DH during puerperium in 1913[2]. Ude and Rigler, in 1929, found multiple pregnancies as a risk factor[3]. Watkin et al[4] made the first laparoscopic repair in puerperium in 1993.

Although a recent systematic review of 43 Bochdalek hernias was published[5], there are still no recommendations and guidelines for this condition during pregnancy. We present the largest systematic review of DH in pregnancy (158 cases) over more than 100 years and propose a treatment algorithm.

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines[6], we performed a systematic review of English-, German-, Spanish-, and Italian-language articles using PubMed, PubMed Central, and Google Scholar (Figure 1). The search items included: 'maternal diaphragmatic hernia, 'congenital hernia', 'pregnancy', 'cardiovascular collapse', 'mediastinal shift', 'abdominal pain in pregnancy', 'hyperemesis', 'diaphragmatic rupture during labor', 'puerperium', 'hernie diaphragmatique maternelle', 'and 'hernia diafragmática congenital'. Additional studies were identified by reviewing reference lists of retrieved studies. Papers in languages other than English were translated using web site deepl.com.

We included all cases and case series identified as having a DH during pregnancy or puerperium (Supplementary material). Exclusion criteria were: (1) Gastroesophageal reflux disease without DH; (2) patients not fulfilling the definition of pregnancy or puerperium; and (3) incomplete data or unavailable full-text articles.

The primary outcome was to identify associations of demographic data (age), obstetric data (trimester of pregnancy, parity), maternal risk factors (such as hypertension, collagen vascular disease, genetic connective tissue disorders), DH-specific data (DH side, DH type, duration of symptoms, time to diagnosis) and therapeutic intervention (type of DH repair, access to DH, type of abdominal wall access, the order of obstetric and surgical procedure) with maternal and fetal outcomes. The secondary outcome was identifying common initial working diagnoses. The study is exempt from ethics approval because we synthesized data from previously published studies.

A data extraction form was prepared and piloted to determine if changes were required before extracting data from the full review. Two authors (DK and VZ) independently performed data extraction following the PRISMA guidelines for data extraction and quality assessment. In addition, the examiners assessed the studies' methodologies according to the tool for evaluating the methodological quality of case reports and case series described by Murad et al[7].

We extracted the following data: publication year; maternal age; obstetric history (parity, the number of prior Cesarean sections); DH type (congenital, posttraumatic, iatrogenic, hiatal, eventration); previous hernia diagnosis and treatment; time of presentation (pregnancy or puerperium), gestational age at presentation or a postpartum day at presentation; symptoms and duration of symptoms before diagnosis; DH side; herniated organs through the DH defect and whether ischemia or perforation occurred; working diagnosis; diagnostic modalities; treatment approaches; time from surgery to delivery/time from delivery to surgery, gestation age at delivery and delivery type, maternal/neonatal outcome. We collected the data that was available from the included studies. However, more than half of the data were missing for several characteristics.

The normality of distribution was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Arithmetical mean, standard deviation, median and interquartile range were used as measures of central tendency. Appropriate parametric or non-parametric tests were then used depending on the normality of the distribution of continuous variables. Categorical variables were presented using contingency tables and were compared with a chi-square test or Fischer's Exact test. Associations between multiple independent variables and a categorical dependent variable were tested using multivariate regression models. Independent variables (i.e., potential confounders) were selected using a combination of rational clinical judgment and directed acyclic graphs. A two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 was used to measure significance. Statistical analysis was done in SPSS v. 21 (IBM Corp., United States).

We report on 158 cases from the 135 studies between 1911 and 2020 in ten languages: English, German, Spanish, Finnish, Dutch, Russian, Korean, French, Turkish, and Danish. To alleviate data analysis, cases were divided into four groups by publication date (Table 1; no published cases between 1956 and 1965). Rather than defining each publication period by a fixed number of years, we grouped a comparable number of studies in each period to allow for a more robust statistical analysis. A similar number of cases were published during the last two decades.

| Year | Counts | % of Total |

| To 1956 | 35 | 22.2 |

| 1965-2000 | 30 | 19.0 |

| 2001-2010 | 43 | 27.2 |

| 2011-2020 | 50 | 31.6 |

The mean maternal age was 28.4 years [SD = 6; median = 27.5; interquartile range (IQR) = 8 years; range 17-45]. Parity distribution was: 0%-43.0%; 1%-30.3%; 2%-14.1%; 3%-6.3%; 4% or more - 6.3%. Nulliparous women were the youngest (mean 27.0 ± 5.4 years), while those with 4 or more children were the oldest (mean 36.0 ± 5.6 years). Also, the mean maternal age rose from 27.6 years (SD = 6.5; median = 25.5; IQR = 7 years) until 1956 to 30.3 years (SD = 5.9; median = 30; IQR = 7.5 years) between 2011–2020.

The proportion of congenital DH increased across all observed periods. In contrast, the trends in the other three major hernia categories appeared stationary (Table 2).

| Period | Congenital | Posttraumatic | Hiatal | During labor | |

| Until 1956 | n | 7 | 1 | 14 | 3 |

| % | 4.4 | 0.6 | 8.9 | 1.9 | |

| 1965-2000 | n | 11 | 7 | 4 | 4 |

| % | 7.0 | 4.4 | 2.5 | 2.5 | |

| 2001-2010 | n | 18 | 17 | 2 | 4 |

| % | 11.4 | 10.8 | 1.3 | 2.5 | |

| 2011-2020 | n | 23 | 9 | 4 | 2 |

| % | 14.6 | 5.7 | 2.5 | 1.3 | |

| Total | 59 | 34 | 24 | 13 | |

DH was mostly diagnosed during pregnancy (n = 124; 82.1%), with the remaining (n = 27; 17.9%) diagnosed before pregnancy (13/27 were operated on before pregnancy; 48.1%). The presentation was slightly different, with most DHs presenting during pregnancy (n = 131; 84.4%) and a minority (n = 24; 15.6%) during puerperium. The mean gestational age at presentation was 23.7 ± 10.7 wk (median = 25.0; IQR = 16.0 wk). This increased significantly from the mean of 19.2 wk (SD=11.0; median=20; IQR = 12 wk) until 1956 to a mean of 24.9 (SD = 9.72; median = 26; IQR = 11 wk) during 2011-2020.

Most DHs were left-sided (n = 124; 83.8%), with a minority on the right (n = 17; 11.5%) or sliding (n = 7; 4.7%). Table 3 shows the hernia types by side. Hiatal hernias (HHs) were omitted because all (n = 14) were left-sided or sliding (n = 7). A left-to-right ratio of DH types was not statistically significant (P = 0.538; Fisher's exact test).

| Side | Congenital | Posttraumatic | During labor | Total |

| Left | 52 | 27 | 10 | 89 |

| Right | 6 | 6 | 2 | 14 |

| L/R ratio | 8, 7 | 4, 5 | 5, 0 | 6, 4 |

| Total | 58 | 33 | 12 | 103 |

The mean duration of symptoms until the diagnosis was 44.0 ± 93.9 d (median = 5.0; IQR = 41.8 d), with almost half (n = 66; 46.2%) presenting within the 3 d. Of those, 44 (30.8%) presented within one day, including 31 (21.7%) with an acute presentation. The mean duration of symptoms decreased during the first period with a mean of 81.1 d (SD = 86.9; median = 60; IQR = 137 d) to a mean of 23.3 d in the last period (SD=41.4; median = 3; IQR = 14.5 d). Although both standard deviations and interquartile ranges point to a wide dispersion of observed values, differences in symptom durations are statistically significant between the four publication periods (P = 0.032; Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA). DHs presenting after delivery or showing major symptoms after delivery had a mean duration of symptoms of 1.9 d (SD = 8.1; median = 0; IQR = 0.13 d), partly due to elevated intraabdominal pressure during delivery.

Table 4 shows symptoms at presentation. Most subjects presented with abdominal symptoms (n = 93; 63.3%), followed by respiratory symptoms (n = 29; 19.7%) and both abdominal and respiratory symptoms (n = 25; 17.0%).

| Abdominal symptoms | Respiratory symptoms | Total | ||

| No | Yes | |||

| No | n | 0 | 29 | 29 |

| % | 0.0 | 19.7 | 19.7 | |

| Yes | n | 93 | 25 | 117 |

| % | 63.3 | 17.0 | 80.3 | |

| Total | n | 93 | 54 | 147 |

| % | 63.3 | 36.7 | 100.0 | |

Table 5 shows that most patients had neither organ ischemia nor perforation (n = 94; 63.9%), followed by ischemia without perforation (n = 24; 16.3%), ischemia with perforation (n = 19; 12.9%) and perforation without ischemia (n = 10; 6.8%).

| Organ ischemia | Organ perforation | Total | ||

| No | Yes | |||

| No | n | 94 | 10 | 104 |

| % | 63.9 | 6.8 | 70.7 | |

| Yes | n | 24 | 19 | 43 |

| % | 16.3 | 12.9 | 29.3 | |

| Total | n | 118 | 29 | 147 |

| % | 80.3 | 19.7 | 100.0 | |

Table 6 shows the proportions of subjects with organ herniation. The stomach was most common (n = 101; 67.3%), followed by the colon (n = 82; 54.7%). Other organs were rarely involved.

| Levels | Counts | % of total |

| Stomach | 101 | 67.3 |

| Colon | 82 | 54.7 |

| Small intestine | 45 | 30.0 |

| Omentum | 32 | 21.3 |

| Spleen | 30 | 20.0 |

| Pancreas | 6 | 4.0 |

| Liver | 5 | 3.3 |

| Eventration | 5 | 3.3 |

| Gallbladder | 1 | 0.7 |

| Kidney | 1 | 0.7 |

Stomach herniation decreased across periods, from 82.8% over 72.4%, 69%, to 54% (P = 0.054; chi-square test). A similar trend was found for the colon, decreasing from 72.4% during 1965-2000 to 56% during 2011-2020 (P < 0.001; chi-square test). Trends for other organs were also noticed but without statistical significance.

Most patients (n = 66; 44.0%) had one herniated organ. A similar proportion was found for two (n = 32; 21.3%) and three (n = 33; 22.0%) herniated organs, while the lowest proportion (n = 19; 12.7%) of four or more herniated organs. The median number of herniated organs declined across observed periods.

A working diagnosis was correct in 50%, including DH (40.7%) and HH (9.3%) (Table 7).

| Diagnosis | Counts | % of total |

| Diaphragmatic hernia | 57 | 40.7 |

| Other | 20 | 14.3 |

| Pneumothorax/hemothorax | 14 | 10.0 |

| Hiatal hernia | 13 | 9.3 |

| Pneumonia/empyema | 11 | 7.9 |

| Labor/pregnancy | 8 | 5.7 |

| Gastroenteritis/GERD | 5 | 3.6 |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 | 2.1 |

| Placental abruption | 3 | 2.1 |

| Preeclampsia | 3 | 2.1 |

| Pancreatitis | 2 | 1.4 |

| Gastroenteritis/pancreatitis | 1 | 0.7 |

In most cases, a chest X-ray was the first diagnostic method (n = 123; 77.8%). Other methods were used in a few cases (Table 8). In 5 subjects, no diagnostic procedure was performed or mentioned.

| Method | Counts | % of total | The year of the 1st mention |

| Initial chest X-ray | 123 | 80.4 | 1943 |

| Obstetric ultrasound | 34 | 22.2 | 1988 |

| Contrast radiography | 33 | 21.6 | 1941 |

| Abdominal ultrasound | 26 | 17.0 | 1991 |

| GI endoscopy | 21 | 13.7 | 1953 |

| Abdominal CT | 15 | 9.8 | 2001 |

| Abdominal radiography | 12 | 7.8 | 1945 |

| Thoracic ultrasound | 10 | 6.5 | 1988 |

| Thoracic MRI | 7 | 4.6 | 2011 |

| Fluoroscopy | 7 | 4.6 | 1941 |

| Abdominal MRI | 4 | 2.6 | 2003 |

| Thoracic CT | 1 | 0.7 | 1999 |

DHs were managed primarily operatively (n = 119; 75.3%). The proportion increased from 25.8% in the first period to 91.7% in the last. Most subjects were operated on during pregnancy (n = 48; 40.3%; rising from 16.7% in the first period to 39.1% in the last). A significant proportion was operated on during delivery (n = 26; 21.8%). The proportion of operations during delivery increased from none until 1956 to 3.3% (1965-2000), 25.6% (2001-2010), and 28% (2011-2020). The remaining 45 subjects (37.8%) were operated on in the puerperium, increasing from 38.5% in the pre-1956 period to 47.8% (1965-2000) and 50.0% (2001-2010), then falling to 37.5% (2011-2020), without statistically significant difference (P = 0.711).

The mean gestational age at surgery was 24.9 ± 3.5 wk (median = 32; IQR = 5.5 wk) for operations during pregnancy and 31.5 ± 3.4 wk (median = 32.0; IQR = 4.5 wk) at delivery. Tables 9 and 10 show surgical access and cruroplasty suture types.

| Levels | Counts | % of total |

| Laparotomy | 53 | 52.5 |

| Thoracotomy | 34 | 33.7 |

| Laparoscopy | 13 | 12.9 |

| Thoracoscopy | 1 | 1.0 |

| Type | Counts | % of total |

| Nonabsorbable | 31 | 48.4 |

| Sutures and mesh | 11 | 17.2 |

| Sutures - unspecified | 9 | 14.1 |

| Mesh | 8 | 12.5 |

| Absorbable | 5 | 7.8 |

In the first period, laparotomy was the most common (n = 5; 83.3%). In the second period (1965–2000), the laparotomy decreased to 36.4% (n = 8), with increased use of thoracotomy (n = 13; 59.1%). In the third period (2001–2010), laparotomies increased to 72.2% (n = 26), and thoracotomies declined to 19.4% (n = 7). Finally, in the period 2011-2020, laparoscopy increased to 24.3% (n = 9), laparotomy declined to 37.8% (n = 14), and thoracotomy increased to 35.1% (n = 13).

In most cases (n = 87; 59.6%), delivery was vaginal (Table 11). An increase in (primarily elective) Cesarean sections (CSs) and a steady decline in vaginal deliveries was detected. The mean gestational age at delivery was 35.8 ± 5.3 wk (median = 38; IQR = 7 wk), with a mean birthweight of 2704 ± 880 g (median = 2750; IQR = 1400 g) and mean birthweight percentile of 45.4 ± 32.3 wk (median = 50.0; IQR = 60.0).

| Period | Delivery type | ||||

| Elective CS | Emergent CS | Vaginal | Total | ||

| Until 1956 | n | 0 | 2 | 27 | 29 |

| % | 0.0 | 6.9 | 93.1 | 100.0 | |

| 1965-2000 | n | 5 | 4 | 20 | 29 |

| % | 17.2 | 13.8 | 69.0 | 100.0 | |

| 2001-2010 | n | 6 | 10 | 24 | 40 |

| % | 15.0 | 25.0 | 60.0 | 100.0 | |

| 2011-2020 | n | 15 | 17 | 16 | 48 |

| % | 31.3 | 35.4 | 33.3 | 100.0 | |

| Total | n | 26 | 33 | 87 | 146 |

| % | 17.8 | 22.6 | 59.6 | 100.0 | |

Table 12 shows the distribution of neonatal outcomes. The proportion of outcomes without complications remained constant (90.3% until 1956 and 85.7% during 2011-2020).

| Complication | Counts | % of total |

| No complications | 128 | 84.2 |

| Intrauterine death | 14 | 9.2 |

| Neonatal death | 4 | 2.6 |

| Miscarriage | 3 | 2.0 |

| Fetal growth restriction | 2 | 1.3 |

| Complications of prematurity | 1 | 0.7 |

The maternal mortality rate was 12.4% (n = 19). Although mortality decreased from 15.6% (n = 5) until 1956 to 6.1% (n = 3) during 2011-2020, the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.379; Fisher's exact test). The maternal outcome was not statistically significantly correlated to the time of operation (P = 0.323; Fisher's exact test), while the neonatal outcome was (P < 0.001; Fisher's test; Table 13). Expectedly, no neonatal complications were associated with operations performed after delivery, while operations performed during pregnancy or delivery were related to neonatal complications in comparable proportions.

| Time of operation | No complications | Complications | Total | |

| After delivery | n | 41 | 0 | 41 |

| % | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | |

| During pregnancy | n | 36 | 11 | 47 |

| % | 76.6 | 23.4 | 100.0 | |

| During delivery | n | 19 | 6 | 25 |

| % | 76.0 | 24.0 | 100.0 | |

| Total | n | 96 | 17 | 113 |

| % | 85.0 | 15.0 | 100.0 | |

The type of DH did not correlate to maternal (P = 0.783) or neonatal (P = 0.344; Fisher's exact test in both cases) outcome.

Regarding delivery type (Table 14), no fatal maternal outcomes during elective CS occurred, compared to 2 deaths during emergent CS and 15 during vaginal deliveries (P = 0.025; Fisher's exact test). Similarly, no neonatal complications were associated with elective CS. Some were observed during emergent CS, with most complications occurring during vaginal deliveries (Table 15; P = 0.039; Fisher's exact test). Although there are statistical differences between maternal and neonatal complications and the delivery mode, this does not necessarily imply causality but a correlation (see the Discussion section).

| Delivery type | Alive | Dead | Total | |

| CS elective | n | 26 | 0 | 26 |

| % | 20.3 | 0.0 | 17.9 | |

| CS emergent | n | 30 | 2 | 32 |

| % | 23.4 | 11.8 | 22.1 | |

| Vaginal | n | 72 | 15 | 87 |

| % | 56.3 | 88.2 | 60.0 | |

| Total | n | 128 | 17 | 145 |

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Delivery type | No complications | Complications | Total | |

| CS elective | n | 26 | 0 | 26 |

| % | 21.0 | 0.0 | 17.9 | |

| CS emergent | n | 26 | 6 | 32 |

| % | 21.0 | 28.6 | 22.1 | |

| Vaginal | n | 72 | 15 | 87 |

| % | 58.1 | 71.4 | 60.0 | |

| Total | n | 124 | 21 | 145 |

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

Gestational age was not correlated with the maternal outcome at either hernia presentation (P = 0.176) or diagnosis (P = 0.763). The same was true for the neonatal outcome and gestational age at hernia presentation (P = 0.226) but not for gestational age at diagnosis (P = 0.042; Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA for all analyses). However, the latter result is most likely the consequence of a positive correlation between the gestational age at diagnosis and gestational age at delivery (P = 0.011; tau b = 0.189; Kendall's correlation), meaning that cases diagnosed later in pregnancy also tended to be delivered later in pregnancy.

The presence and absence of abdominal or respiratory symptoms did not correlate significantly to working diagnosis (P = 0.903 and P = 0.250, respectively; Fisher's test). All sliding hernias had abdominal symptoms (Table 16), but none had respiratory symptoms (Table 17). Generally, most DHs had abdominal symptoms, with a lower proportion of respiratory symptoms (see also Table 4).

| Symptoms | Left | Right | Sliding | Total | |

| No | n | 28 | 4 | 0 | 32 |

| % | 22.8 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 21.9 | |

| Yes | n | 95 | 12 | 7 | 114 |

| % | 77.2 | 75.0 | 100.0 | 78.1 | |

| Total | n | 123 | 16 | 7 | 146 |

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Symptoms | Left | Right | Sliding | Total | |

| No | n | 75 | 8 | 7 | 90 |

| % | 62.5 | 50.0 | 100.0 | 62.9 | |

| Yes | n | 45 | 8 | 0 | 53 |

| % | 37.5 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 37.1 | |

| Total | n | 120 | 16 | 7 | 143 |

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

DH type correlated with surgical intervention, i.e., there was a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001; Fisher's exact test) in the proportion of operated vs nonoperated hernias by type (Table 18). However, the same was not true regarding the type of surgical access (laparoscopy, laparotomy, or thoracotomy; P = 0.486; Fisher's exact test).

| Hernia type | Not operated | Operated | Total | |

| Congenital | n | 5 | 53 | 58 |

| % | 8.6 | 91.4 | 100.0 | |

| Posttraumatic | n | 4 | 30 | 34 |

| % | 11.8 | 88.2 | 100.0 | |

| During labor | n | 3 | 10 | 13 |

| % | 23.1 | 76.9 | 100.0 | |

| Hiatal | n | 13 | 10 | 23 |

| % | 56.5 | 43.5 | 100.0 | |

| Total | n | 25 | 103 | 128 |

| % | 19.5 | 80.5 | 100.0 | |

The timing of diagnosis (before vs after pregnancy) did not correlate with the presence of abdominal (P = 0.427) or respiratory (P = 0.494; Fisher's exact test) symptoms compared to those diagnosed during pregnancy.

There were statistically significant differences in neonatal weight percentile (P = 0.025) but not in the gestational age (P = 0.548; Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA) between antenatal, intrapartum, or postnatal DH operations. The statistical significance of differences results from differences between hernias operated during delivery vs after delivery (P = 0.019) or in pregnancy (P = 0.070; Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Fligner pairwise comparison; Table 19). Results should be interpreted cautiously due to the small number of observations per group.

| Surgery | N | M | Med | SD | Min | Max |

| After pregnancy | 12 | 2811 | 2910 | 812 | 1370 | 3640 |

| During pregnancy | 16 | 2676 | 2880 | 948 | 500 | 4100 |

| During delivery | 8 | 1819 | 1995 | 487 | 960 | 2390 |

(Symptomatic) DH in pregnancy is exceedingly rare, with the collection of 43 maternal Bochdalek hernia cases from 1941 to 2020[5]. We collected 158 cases, although an additional number was unavailable or with incomplete data. Some claimed that paraesophageal or HHs are up to six times more prevalent in pregnant patients[8], although pregnancy could be a risk factor for symptomatic but not overall DH. In pregnant patients with abdominal complaints, DH was demonstrated in 12.8% (multiparas 18.1%, primiparas 5.1%)[9]. Hernias disappeared in over two-thirds of reexamined patients. On the other hand, DH can be overlooked because the symptoms were attributed to physiologic vomiting of pregnancy, hyperemesis gravidarum, or reluctance to use diagnostic irradiation modalities. Similar to Choi et al[5], our results show a high incidence in primiparas and multiparas.

Until 1935, 0.75%-1% of X-ray examinations of the stomach showed HH in the general population[9,10]. In that era, it was difficult to differentiate between regurgitation into the esophagus and actual herniation[9]. Currently, in the general population, sliding HH is the commonest (95%), with the prevalence of each other type of less than 1%[11]. The prevalence of Bochdalek's hernia ranges from 1/2000–1/7000 based on autopsy studies[12,13] to 6% based on early-era computed tomography examinations[14] and 0.17% in 1998[15]. Females comprise at least ¾[3,15].

Our results show an increasing maternal age across observed periods. It follows the increasing incidence of congenital DH only. The explanation could be higher tissue elasticity in younger patients and lower incidence of multiparas in younger ages, as observed in 1929[3]. In 1935, multiparas had a higher incidence of DH[9]. Our results show a decreasing symptomatic DH rate with increasing parity. One of the explanations could be that "traumatized" or operated patients avoid future pregnancies to eliminate repeated stress during subsequent pregnancies. An increase in posttraumatic DH rate is expected due to the growing population, and higher automobile use increases the rate of blunt abdominal trauma or falls. Better diagnostics and awareness of diaphragm injury from blunt abdominal trauma resulted in more diaphragmatic lacerations treated during the initial traumatic event resulting in a stable number of posttraumatic DH. The mean gestational age at presentation increased from a mean of 19.2 wk to a mean of 24.9 wk. Better obstetric care allowed for delaying invasive treatments when fetal viability is reached.

Several mechanisms could result in maternal complications of DH. An expanding uterus increases intra-abdominal pressure displacing mobile organs. An additional increase in intra-abdominal pressure occurs during vaginal delivery with forceful contractions of abdominal wall musculature. Abdominal organs in the chest may displace mediastinal structures[15]. Compression of the vena cava may impair venous return, producing hypotension[16]. Lung compression may lead to hypoxia and dyspnea[17]. Bowel compression may result in obstruction, strangulation, ischemia, or necrosis of the strangulated bowel.

Although the age during pregnancy could be a risk factor for DH, the increasing age of primiparas did not result in a steep increase in DH occurrence in pregnancy. Tissue elasticity may not change from 19 to 25 years of age.

Most DHs were left-sided (83.8%), similar to the general population for Bochdalek[12] and posttraumatic hernias[18]. Stomach herniation decreased from 82.8%, 72.4%, and 69% to 54%. A similar trend was found for the colon, decreasing from 72.4% to 56%. The median number of herniated organs also declined, and earlier detection resulted in more DHs without organs.

The mean duration of symptoms before diagnosis was 44 d, with close to half of the cases presenting within 3 d. Symptomatic hernias after delivery had a mean duration of symptoms of 1.9 d.

Abdominal or respiratory symptoms did not correlate to a working diagnosis. All sliding hernias had abdominal without respiratory symptoms, while most DHs had abdominal symptoms, and some had respiratory symptoms. Diagnosis of hernia (before vs after pregnancy) did not correlate with abdominal or respiratory symptoms compared to those diagnosed during pregnancy. The most common respiratory symptoms were chest pain and dyspnea, while abdominal pain was commonly one-sided, sometimes with shoulder (tip) pain. We found a higher incidence of abdominal complaints (80.3%) than Choi et al[5] (65%), which included only Bochdalek’s hernias. However, the incidence, specific herniated organs (stomach and colon), and the number of herniated organs were similar.

The working diagnosis of DH was correct in 50%. DH was mostly diagnosed during pregnancy (82.1%). Half of the remaining 17.9% diagnosed before pregnancy were operated on before pregnancy. A chest X-ray was the first imaging method (77.8%). Other imaging methods were rarely used.

The proportion of operated DHs during pregnancy depended on the DH type – congenital 91.4%, posttraumatic 88.2%, during delivery 76.9%, and HH only 43.5%. DHs were managed mostly operatively (75.3%) except HH. The proportion increased from 25.8% to 91.7%. This means less reluctance to operate on pregnant patients with good results. The timing of surgical and obstetrical management depends on the severity of DH presentation and fetal status (Figure 2).

Asymptomatic DH: Contrary to Choi et al[5], we do not recommend the operation of asymptomatic maternal DH because surgery can provoke uterine contractions in pregnancies over 28 gestational weeks increasing the risk of prematurity[19]. Close monitoring suffices. Induced (assisted) vaginal delivery should be made after 34 wk. Another option is a CS through Pfannenstiel incision after 34 wk of gestation. After puerperium or breastfeeding, elective laparoscopic DH repair results in minimal abdominal wall trauma with excellent cosmetic results.

Symptomatic DH: Although Choi et al[5] recommended aggressive surgical management despite fetal viability, sometimes symptoms can be tolerated under close monitoring, prolonging pregnancy until fetal viability. Parenteral nutrition should be administered with inadequate maternal caloric intake or intermittent vomiting in perioperative or nonoperative settings[20]. We mostly agree with Choi et al[5] for the enteral and parenteral routes except for feeding jejunostomy, which is an aggressive and unnecessary procedure. DH repair results in early maternal postoperative peroral nutrition.

Fetal growth assessment is mandatory. Between 24 and 34 gestational weeks, steroid administration for fetal lung maturation should be simultaneous with maternal nasogastric decompression until (transfer to the tertiary center and) surgery. Symptomatic non-strangulated DH has three surgical-gynecological strategies. Without fetal distress, (laparoscopic) DH repair is followed with fetal cardiotocographic monitoring. Another option is a CS through Pfannenstiel incision with laparoscopic DH repair after Pfannenstiel incision closure, resulting in minimal maternal abdominal wall trauma. The third option is total median laparotomy, lower for CS and upper for DH repair. This mutilating option aggravates breastfeeding and maternal newborn care, increasing the risk of incisional hernia. Choi et al[5] also recommend subcostal incision but do not explain the steps for simultaneous fetal delivery. Such an approach results in two abdominal wall incisions (subcostal and Pfannenstiel), again a mutilating option for the mother.

Strangulated DH: Presentation of less than 3 d carries a risk of strangulation in pregnancy. We found a slightly lower incidence of strangulation (36.1%) than Choi et al[5] (44%). Choi et al[5] analyzed a specific type of DH, and some patients with bowel obstruction, which is not strangulation, could be wrongly included in this subgroup. Strangulated DH with captured air in hollow abdominal organs in the thorax is sometimes misdiagnosed as pneumothorax. Chest drain insertion may lead to bowel perforation, illustrating why chest drains should be inserted using blunt dissection. Transudate from obstructed hollow abdominal viscera should be suspected when serosanguinous[21] or straw-colored fluid[20] is detected in the chest drain.

Surgical access for DH: Surgical access to DH changed during the observed period. While there were variations in the incidence of thoracotomy (increased in the final period), laparoscopy was increasingly used. Laparoscopic access is recommended in the general population[22], resulting in faster recovery, earlier ambulance, less analgesia, and less risk of thromboembolic incidents. We recommend a laparoscopic approach in pregnancy.

The delivery was mainly vaginal (59.6%), although a steady decline was evident, with a constant rise in CS. The mean gestational age at delivery was 35.8 ± 5.3 wk, with a mean weight of 2704 ± 880 g. Delaying the delivery results in near-term babies with fewer complications from prematurity.

Maternal outcome: Half of maternal DH diagnosed before pregnancy were operated on before pregnancy (13/27) but developed recurrent DH during pregnancy. Although the number of women with prepregnancy DH repair worldwide is unknown, we assume that prepregnancy repair is a risk factor for (recurrent) DH during pregnancy. Due to the lack of long-term follow-up, it is unknown whether DH repair during pregnancy, labor, or even puerperium is the risk factor for a recurrent DH after pregnancy. The type of DH did not correlate to the maternal outcome.

The highest maternal mortality was associated with vaginal delivery. Fortunately, vaginal delivery was not the cause of detrimental outcomes. First, the highest number of cases were delivered vaginally. Second, unstable mothers either died or were treated with an emergent DH repair, during which the fetus died (see Neonatal outcome). Fetal death detected after the operation indicated induced vaginal delivery as the initial management. In other words, a delay in DH repair and not the type of delivery increases maternal mortality. Also, earlier surgery, sometimes with earlier delivery of a viable fetus (primarily by CS), leads to the conclusion that vaginal delivery increases maternal mortality.

Maternal outcome did not correlate with gestational age at hernia presentation or diagnosis.

Neonatal outcome: The obstetric complication rates were more frequent in the third trimester of pregnancy. Until 1988, fetal deaths occurred in 50% and premature birth in 24%[23]. CS delivery was done in 30% of reported cases[24]. Recent literature reviews claim an overall fetal mortality rate of 13%-19%[25,26], similar to our results (13.8%). Mothers with cardiac arrest from DH have a fetal mortality rate of 50%[16,24,27-30]. DH type did not correlate to neonatal outcomes.

In our study, the highest neonatal mortality was with vaginal delivery. The explanation is the same as for maternal outcomes related to vaginal delivery. Many cases had confirmed intrauterine fetal death, mostly from maternal shock or maternal death when induced vaginal delivery was indicated. Also, in many cases, these were previable pregnancies, and again, fetal death was from maternal metabolic or respiratory acidosis. In such cases, earlier surgical management, not the type of delivery, saves the mother and fetus.

Gestational age at hernia presentation did not correlate with the fetal outcome, but the gestational age at diagnosis did. This is most likely the consequence of a positive correlation between the gestational age of diagnosis and gestational age at delivery, meaning that cases diagnosed later in pregnancy (probably due to less pronounced clinical presentation) also tended to be delivered later in pregnancy. Less pronounced clinical picture results in more prolonged pregnancy before intervention.

Limitations of the study: Despite the high number of cases, these were published over a century. Older studies have limited value today, primarily in surgical and obstetric aspects. Conservative treatment was similar 100 years ago and today, except for parenteral nutrition, which has limited influence on maternal outcomes.

The proportion of congenital hernias increased, while the other types of DH appeared stationary. Most DHs were left-sided (83.8%). The median number of herniated organs declined across observed periods. A working diagnosis was correct in 50%. DH type did not correlate to maternal or neonatal outcomes. Laparoscopic access increased while thoracotomy varied across periods. Presentation of less than 3 d carried a significant risk of strangulation in pregnancy. The clinical presentation of DH is easily confused with common chest conditions, delaying the diagnosis, and increasing maternal and neonatal mortality. Symptomatic DH should be included in the differential diagnosis of pregnant women with abdominal pain associated with dyspnea and chest pain, especially when followed by collapse. Early diagnosis and immediate intervention lead to excellent maternal and fetal outcomes. Strangulated DH requires an emergent operation, while delivery should be based on obstetric indications.

Diaphragmatic hernia (DH) is extremely rarely described during pregnancy. Due to the rarity, there is no diagnostic or treatment algorithm for DH in pregnancy.

Although rare, such cases can be found in clinical practice, and immediate intervention is necessary. Due to the lack of guidelines on the subject, it is difficult to make correct decisions. A review article on the subject would simplify the decision process.

To summarize and define the most appropriate diagnostic methods and therapeutic options for DH in pregnancy based on scarce literature.

A literature search of English-, German-, Spanish-, and Italian-language articles were performed using PubMed (1946–2021), PubMed Central (1900–2021), and Google Scholar. The PRISMA protocol was followed. Demographic, imaging, surgical, and obstetric data were obtained.

The average maternal age increased. The proportion of congenital hernias increased, while the other types appeared stationary. Most DHs were left-sided (83.8%). The median number of herniated organs declined. A working diagnosis was correct in 50%. DH type did not correlate to maternal or neonatal outcomes. Laparoscopic access increased while thoracotomy varied. Presentation of less than 3 d carried a significant risk of strangulation in pregnancy.

The clinical presentation of DH is easily confused with common chest conditions, delaying the diagnosis, and increasing maternal and neonatal mortality. Symptomatic DH should be included in the differential diagnosis of pregnant women with abdominal pain associated with dyspnea and chest pain, especially when followed by collapse. Early diagnosis and immediate intervention lead to excellent maternal and fetal outcomes. Strangulated DH requires an emergent operation, while delivery should be based on obstetric indications.

Diagnostic, surgical, and obstetric findings of this study will shorten the diagnostic delay of DH. Also, earlier and more beneficial surgical and obstetric management would reduce maternal complications and fetal mortality.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: Dominican republic

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: He Z, China; Tovar JA, Spain S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Crump WG. Diaphragmatic hernia with rupture complicating a three months’ pregnancy. J Am Inst Homeopath. 1911;4:633-637. |

| 2. | Müller RO. Ileus in der Schwangerschaft infolge eingeklemmter Zwerchfellshernie. 1913. |

| 3. | Ude LG WR. Hernia of the diaphragm through the esophageal hiatus with report of nineteen cases. Minn Med. 1929;12:751-758. |

| 4. | Watkin DS, Hughes S, Thompson MH. Herniation of colon through the right diaphragm complicating the puerperium. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1993;3:583-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Choi JY, Yang SS, Lee JH, Roh HJ, Ahn JW, Kim JS, Lee SJ, Lee SH. Maternal Bochdalek Hernia during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of Case Reports. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Brooke BS, Schwartz TA, Pawlik TM. MOOSE Reporting Guidelines for Meta-analyses of Observational Studies. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:787-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 98.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018;23:60-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1008] [Cited by in RCA: 1538] [Article Influence: 219.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Åkerlund Å. I. Hernia Diaphragmatica Hiatus Oesophagei Vom Anatomischen und Rontgenologischen Gesichtspunkt. Acta Radiol. 1926;6:3-22. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rigler LG, Eneboe JB. The incidence of hiatus hernia in pregnant women and its significance. J Thorac Surg. 1935;4:262-268. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Ritvo M. Hernia of the stomach through the esophageal orifice of the diaphragm. JAMA. 1930;94:15-21. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Hiroshi I. X-ray finding of esophageal hiatus hernia - Classification of degree of hernia. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 1985;18:1-7. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Nitecki S, Bar-Maor JA. Late presentation of Bochdalek hernia: our experience and review of the literature. Isr J Med Sci. 1992;28:711-714. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Salaçin S, Alper B, Cekin N, Gülmen MK. Bochdalek hernia in adulthood: a review and an autopsy case report. J Forensic Sci. 1994;39:1112-1116. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Gale ME. Bochdalek hernia: prevalence and CT characteristics. Radiology. 1985;156:449-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mullins ME, Stein J, Saini SS, Mueller PR. Prevalence of incidental Bochdalek's hernia in a large adult population. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:363-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ortega-Carnicer J, Ambrós A, Alcazar R. Obstructive shock due to labor-related diaphragmatic hernia. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:616-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hill R, Heller MB. Diaphragmatic rupture complicating labor. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27:522-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Okan I, Baş G, Ziyade S, Alimoğlu O, Eryılmaz R, Güzey D, Zilan A. Delayed presentation of posttraumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2011;17:435-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fu PH, Yu CH, Chen YC, Chu CC, Chen JY, Liang FW. Risk of adverse fetal outcomes following nonobstetric surgery during gestation: a nationwide population-based analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Williams M, Appelboam R, McQuillan P. Presentation of diaphragmatic herniae during pregnancy and labour. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2003;12:130-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wolfe CA, Peterson MW. An unusual cause of massive pleural effusion in pregnancy. Thorax. 1988;43:484-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fernández-Moreno MC, Barrios Carvajal ME, López Mozos F, Garcés Albir M, Martí Obiol R, Ortega J. When laparoscopic repair is feasible for diaphragmatic hernia in adults? A retrospective study and literature review. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:3347-3355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kurzel RB, Naunheim KS, Schwartz RA. Repair of symptomatic diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:869-871. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Eglinton T, Coulter GN, Bagshaw P, Cross L. Diaphragmatic hernias complicating pregnancy. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:553-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chen Y, Hou Q, Zhang Z, Zhang J, Xi M. Diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy: a case report with a review of the literature from the past 50 years. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:709-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Reddy M, Kroushev A, Palmer K. Undiagnosed maternal diaphragmatic hernia - a management dilemma. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Jacobs R, Honore PM, Hosseinpour N, Nieboer K, Spapen HD. Sudden cardiac arrest during pregnancy: a rare complication of acquired maternal diaphragmatic hernia. Acta Clin Belg. 2012;67:198-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Karabacak P, Osmanlıoğlu HÖ, Ceylan BG, Yağlı MA, Yıldırım MK. Cardiac arrest in a pregnant patient diagnosed with Bochdalek hernia. Journal of Clinical and Analytical Medicine. 2016;7:746-748. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Indar A, Bornman PC, Beckingham IJ. Late presentation of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia in pregnancy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83:392-393. [PubMed] |