Published online Sep 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i26.6298

Peer-review started: June 21, 2023

First decision: July 28, 2023

Revised: August 11, 2023

Accepted: August 23, 2023

Article in press: August 23, 2023

Published online: September 16, 2023

Processing time: 79 Days and 1.2 Hours

Pancreatic walled-off necrosis (WON) rarely causes critical gastric necrosis and perforation, which may develop when pancreatic WON squashes against the stomach. The Atlanta 2012 guidelines were introduced for acute pancreatitis and its related clinical entities. However, there are few reported cases describing the clinical course and resolution of pancreatic WON.

We report the case of a 45-year-old man who presented to the urgent emergency department with gastric perforation caused by a severe complication of pancreatic WON on computed tomography. The patient underwent an emergency distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy, and gastric wedge resection. Postoperative findings showed re-perforation of the gastric wall at a previously resected margin. Furthermore, endoscopic examination revealed an ulcerative area with a defect in the fundus. After diagnostic endoscopy, endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure was performed, and continuous suction was transferred over all tissues in contact with the sponge surface. The patient recovered without any further complications and was discharged in good condition at postoperative week 8. No recurrence occurred during the 6-mo follow-up period.

When managing a patient with serious gastric perforation complicated by pancreatic WON, a multidisciplinary treatment approach should be considered.

Core Tip: Pancreatic walled-off necrosis (WON) rarely causes critical gastric necrosis and perforation. Cases of successful resolution of gastric perforation complicated by pancreatic WON are hardly encountered. Due to their rarity, discussing each clinical experience is necessary.

- Citation: Noh BG, Yoon M, Park YM, Seo HI, Kim S, Hong SB, Park JK, Lee MW. Successful resolution of gastric perforation caused by a severe complication of pancreatic walled-off necrosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(26): 6298-6303

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i26/6298.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i26.6298

Pancreatic walled-off necrosis (WON) developing in the course of necrotizing pancreatitis occurs 4 or more weeks after its onset[1]. Although systemic inflammation commonly wanes 14 d after the onset of symptoms, infected necrosis progresses in approximately 30% of patients with necrotizing pancreatitis[2]. Gastric complication related to pancreatic WON is a rare complication of acute pancreatitis. To date, cases of gastric perforation, a serious complication of pancreatic WON, are hardly encountered and similar cases to ours are few[3-5]. Successful resolution in cases of gastric perforation complicated by pancreatic WON is hardly seen. Due to their rarity, discussing each clinical experience is necessary. Moreover, we are eager that clinicians will gain a better understanding of the clinical course of gastric complications related to WON.

A 45-year-old man, drinking at least 3 times a week for 3 mo due to social and personal issues, presented with abdominal pain for 21 d.

The patient reported no present illness.

The patient reported no past illness.

The patient reported no relevant medical or family history.

Upon presentation, the patient’s vital signs were stable. However, he showed paleness. Physical examination revealed signs of peritoneal irrigation such as a distended abdomen with rigidity and tenderness in the epigastric region.

Table 1 reveals biochemistry values upon admission.

| Value | Unit | Reference range | On admission |

| White blood cell count | 109/uL | 3.8-11.0 | 12.78 |

| Neutrophil count | 109/uL | 1.5-7.0 | 9.25 |

| Hemoglobin | g/dL | 13.5-17.5 | 8.40 |

| Hematocrit | % | 39.0-53.0 | 25.00 |

| Platelet count | 109/uL | 140-420 | 697.00 |

| C-reactive protein | mg/dL | 0-0.5 | 9.24 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | U/L | 135-225 | 274.00 |

| Lactic acid | mmol/L | 0.7-2.5 | 2.20 |

| Sodium | mmol/L | 138-148 | 119.00 |

| Potassium | mmol/L | 3.5-5.3 | 3.69 |

| Serum amylase | U/L | 36-128 | 29.30 |

| Serum lipase | U/L | 22-51 | 80.10 |

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed, adjacent to the huge WON, wall defect, demonstrating a perforation in the stomach fundus and splenic infarction. Contrast-enhanced CT scanning demonstrated the huge WON at the intra- and extrapancreatic areas (Figure 1A and B).

Based on the preoperative CT and histopathology results, the final diagnosis was gastric perforation caused by a severe complication of pancreatic WON.

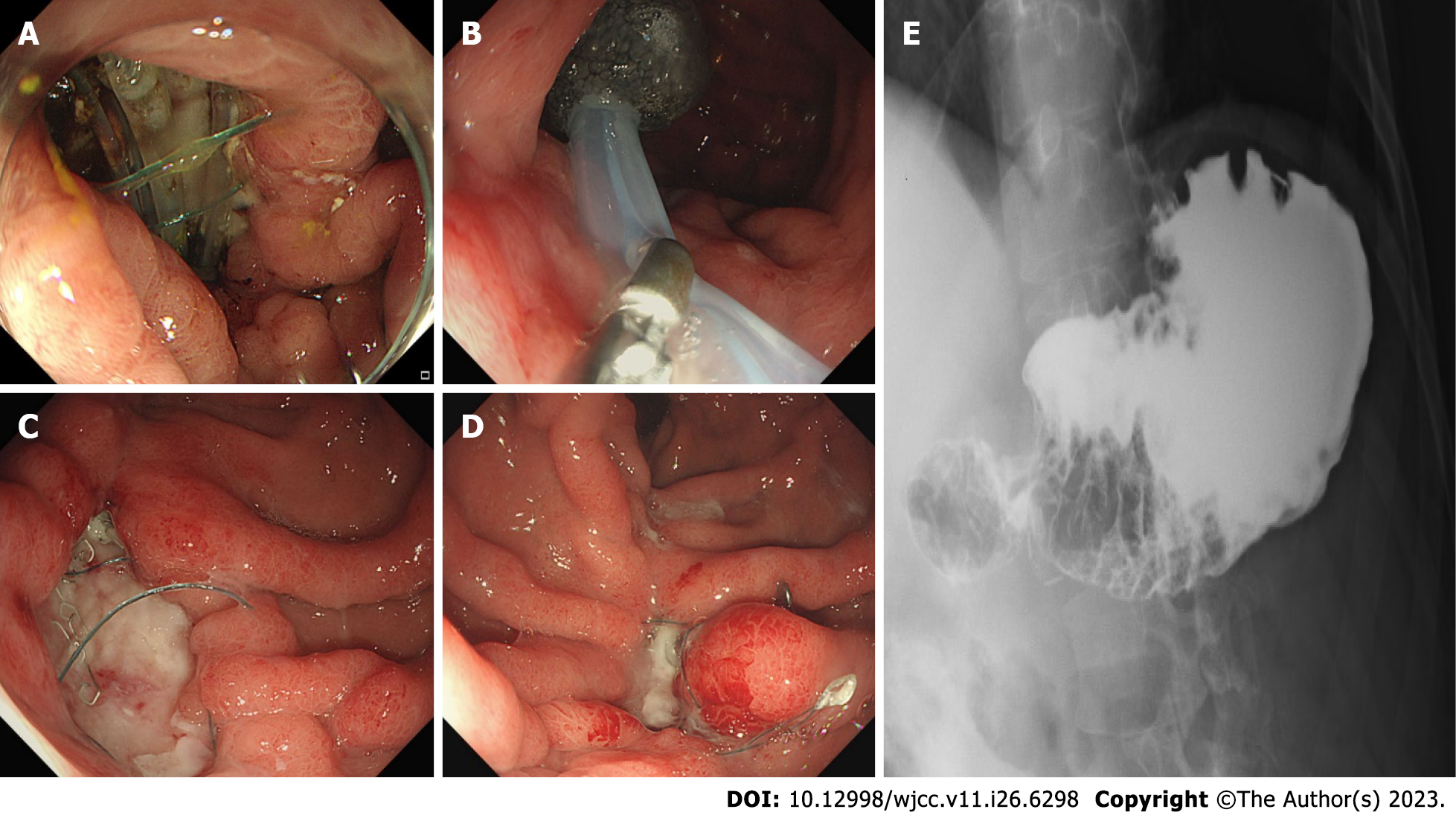

Ceftriaxone and metronidazole were initially administered. After identifying the organisms, piperacillin-tazobactam, fluconazole, and vancomycin were administered after consultation with infectious disease specialists. Postoperative serum amylase and lipase levels were within the normal range. Drain fluid amylase was 1052 U/L at postoperative day (POD) 1 and 17.6 U/L at POD 7. After necrosectomy, the patient received supportive medical treatment, including parenteral nutrition and diet, starting on POD 7. Thereafter, the patient suddenly experienced unsuspected abdominal discomfort at POD 18. Follow-up CT (Figure 1C and D) and endoscopy revealed a 3-cm gastric perforation at the anastomotic site (Figure 2A). Reoperation was not an option due to severe inflammation. Based on discussions with gastroenterologists, endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure (EVAC) was performed, and continuous suction was applied to the perforated site through a nasogastric drainage tube with a polyurethane sponge (KCI Inc., San Antonio, TX, United States) (Figure 2B). Surgical drain was removed due to maintaining a negative pressure on sponge. Drain fluid amylase level was 3.0 U/L and had an output of < 20 mL. EVAC treatment was continued for 3 wk with sponge exchange every 72 h until the wound cavity had healed (Figure 2C and D). Follow-up upper gastrointestinal series showed no contrast leakage from the stomach (Figure 2E). The patient was discharged in good condition at postoperative week 8.

At the 3-mo follow-up, CT showed significant improvement (Figure 1E and F). The patient was followed up as an outpatient for 6 mo without showing recurrence or readmission event including glucose control, and is doing well at work after getting a job.

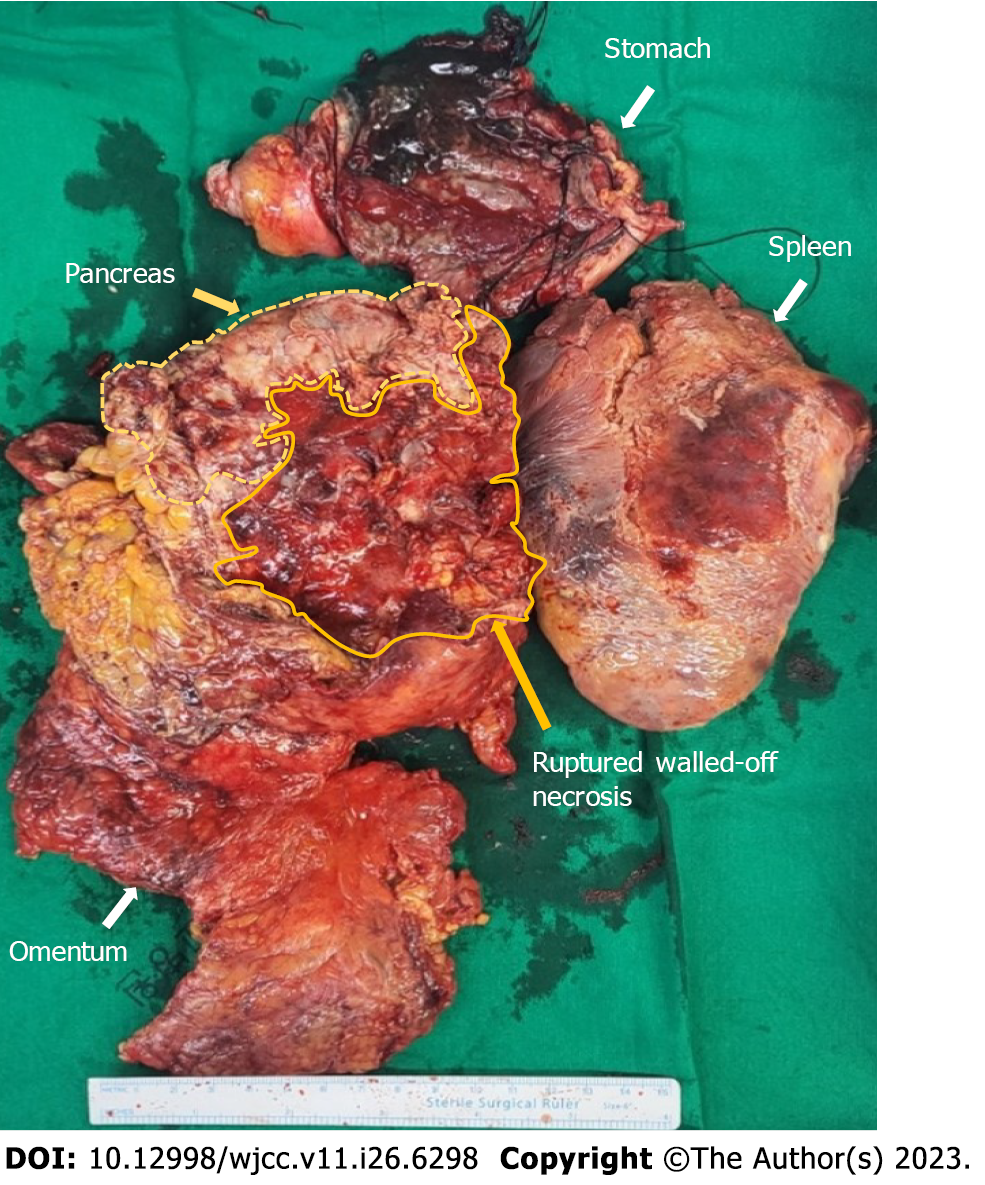

The Atlanta Symposium (2012) introduced guidelines to globalize the definitions of acute pancreatitis and related clinical entities[6]. Of all the entities, necrotizing pancreatitis most commonly manifests as necrosis involving both the pancreatic and peripancreatic tissues[7]. Pancreatic necrosis constitutes substantial additional morbidity, with mortality rates as high as 20%-30%[8]. Surgical volumes of interventions have significantly decreased over the years, as minimally invasive strategies have proven effective[9]. However, emergency surgery, irrespective of time, is indicated for cases of gastrointestinal perforation caused by necrotizing pancreatitis[10]. Pancreatic WON is a mature, encapsulated, acute necrotic collection with a well-defined inflammatory wall observed on contrast-enhanced CT. Our patient showed a heterogeneous, fully encapsulated collection with small air pockets inside the cyst and near the peritoneal space. Conventional management of infected WON depends on the availability of expertise and severity of the comorbid medical status. Endoscopic drainage is a commonly used procedure in patients without gastrointestinal perforation. However, there is a high complication rate and longer hospital stay associated with drainage procedures[11]. From the point of view of surgical management of necrotizing pancreatitis, a previous report has emphasized that formal resection should be avoided to lower the event of bleeding and fistula formation and protect normal tissue. Thus, repeated debridements with continuous drainage were commonly performed. However, those procedures could be usually associated with immediate and long-term complications such as gastrointestinal perforation, infection, organ failure, and fistula. Morbidity rates of 34%-95% have been reported[7,9]. In our case, we initially performed formal distal pancreatectomy and adjacent necrotic tissue resection with surgical drainage (Figure 3). Cholecystectomy was not performed because there was no evidence of gallstone pancreatitis. Regarding gastric perforation with pancreatic WON, there are no surgical guidelines due to the rarity of this disease entity. We suggest that formal resection would be a better procedure for removing necrotic tissue as much as possible without further surgical debridement. Reperforation occurred during postoperative care with proper conservative care, including nutritional support and antibacterial therapy with antifungal agents. In terms of complications, suitable treatment in patients with gastric perforation requires collaboration among surgeons, radiologists, and gastroenterologists. Endoscopic closure techniques are promising alternatives to surgical treatment[12]. A retrospective study including 71 patients compared stent placement with EVAC for nonsurgical closure of intrathoracic leakage. The overall closure rate was higher in the EVAC group (84.4%) than in the stent group (53.8%). EVAC appears to be an effective alternative to other methods for treating anastomotic leaks[13]. After diagnostic endoscopy, the sponge was placed at the leakage site and released using a pusher. Our patient changed sponges seven times over 3 wk. After successful resolution, the patient was initiated on an oral diet without complications. Clinical cases showing resolution of pancreatic WON with gastric perforation is hardly reported. Therefore, discussing multidisciplinary clinical approaches is essential.

Encountering a patient with serious gastric perforation complicated by pancreatic WON, formal distal pancreatectomy, adjacent necrotic tissue resection, and surgical drainage with a multidisciplinary treatment approach could be considerable options for improving the therapeutic outcome.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Angst E, United States; Cabezuelo AS, Spain; Giacomelli L, Italy S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Beger HG, Rau BM. Severe acute pancreatitis: Clinical course and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5043-5051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, Boermeester MA, Nieuwenhuijs VB, van Goor H, Dejong CH, Schaapherder AF, Gooszen HG; Dutch Acute Pancreatitis Study Group. Timing and impact of infections in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2009;96:267-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rieger A, Bachmann J, Schulte-Frohlinde E, Burzin M, Nährig J, Friess H, Martignoni ME. Total gastric necrosis subsequent to acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2012;41:325-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Madhyastha SP, Banda GR, Acharya RV, Balaraju G. Spontaneous rupture of pancreatic pseudocyst into the stomach. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bansal A, Gupta P, Singh H, Samanta J, Mandavdhare H, Sharma V, Sinha SK, Dutta U, Kochhar R. Gastrointestinal complications in acute and chronic pancreatitis. JGH Open. 2019;3:450-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4338] [Article Influence: 361.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 7. | Freeman ML, Werner J, van Santvoort HC, Baron TH, Besselink MG, Windsor JA, Horvath KD, vanSonnenberg E, Bollen TL, Vege SS; International Multidisciplinary Panel of Speakers and Moderators. Interventions for necrotizing pancreatitis: summary of a multidisciplinary consensus conference. Pancreas. 2012;41:1176-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Yang Y, Zhang Y, Wen S, Cui Y. The optimal timing and intervention to reduce mortality for necrotizing pancreatitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. World J Emerg Surg. 2023;18:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kokosis G, Perez A, Pappas TN. Surgical management of necrotizing pancreatitis: an overview. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16106-16112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | El Boukili I, Boschetti G, Belkhodja H, Kepenekian V, Rousset P, Passot G. Update: Role of surgery in acute necrotizing pancreatitis. J Visc Surg. 2017;154:413-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hookey LC, Debroux S, Delhaye M, Arvanitakis M, Le Moine O, Devière J. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic-fluid collections in 116 patients: a comparison of etiologies, drainage techniques, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:635-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rogalski P, Daniluk J, Baniukiewicz A, Wroblewski E, Dabrowski A. Endoscopic management of gastrointestinal perforations, leaks and fistulas. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:10542-10552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Brangewitz M, Voigtländer T, Helfritz FA, Lankisch TO, Winkler M, Klempnauer J, Manns MP, Schneider AS, Wedemeyer J. Endoscopic closure of esophageal intrathoracic leaks: stent versus endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure, a retrospective analysis. Endoscopy. 2013;45:433-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |