Published online Sep 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i26.6206

Peer-review started: May 6, 2023

First decision: August 4, 2023

Revised: August 17, 2023

Accepted: August 23, 2023

Article in press: August 23, 2023

Published online: September 16, 2023

Processing time: 124 Days and 10.1 Hours

Patients with trisomy 8 consistently present with myeloid neoplasms and/or auto-inflammatory syndrome. A possible link between myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) with trisomy 8 (+8-MDS) and inflammatory disorders is well recognized, several cases having been reported. However, inflammatory disorders in patients without MDS have been largely overlooked. Generally, Behçet's disease is the most common type in +8-MDS. However, inflammatory disorders with pulmonary involvement are less frequent, and no effective treatment has been established.

A 27-year-old man with recurrent fever, fatigue for > 2 mo, and unconsciousness for 1 day was admitted to our emergency department with a provisional diagnosis of severe pneumonia. Vancomycin and imipenem were administered and sputum collected for metagenomic next-generation sequencing. Epstein–Barr virus and Mycobacterium kansasii were detected. Additionally, chromosomal analysis showed duplications on chromosome 8. Two days later, repeat metagenomic next-generation sequencing was performed with blood culture. Cordyceps portugal, M. kansasii, and Candida portugal were detected, and duplications on chromosome 8 confirmed. Suspecting hematological disease, we aspirated a bone marrow sample from the iliac spine, examination of which showed evidence of infection. We added fluconazole as further antibiotic therapy. Seven days later, the patient’s condition had not improved, prompting addition of methylprednisolone as an anti-inflammatory agent. Fortunately, this treatment was effective and the patient eventually recovered.

Severe inflammatory disorders with pulmonary involvement can occur in patients with trisomy 8. Methylprednisolone may be an effective treatment.

Core Tip: Trisomy 8 patients without myelodysplastic syndrome consistently present with auto-inflammatory syndrome, the gastrointestinal tract being the most commonly affected site. Because initial presentations with severe pneumonia are less common in trisomy 8 patients, there is limited experience on treating this. We treated a 27-year-old patient with trisomy 8 who was diagnosed with severe pneumonia and responded to methylprednisolone. The patient was eventually discharged in good clinical condition. This case shows that, in trisomy 8 patients, severe inflammatory disorders with pulmonary involvement can occur before progression to hematological malignancies. Steroids may play an important role in treating these patients.

- Citation: Pan FY, Fan HZ, Zhuang SH, Pan LF, Ye XH, Tong HJ. Severe inflammatory disorder in trisomy 8 without myelodysplastic syndrome and response to methylprednisolone: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(26): 6206-6212

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i26/6206.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i26.6206

There have been several published reports on inflammatory disorders in trisomy 8 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS)[1-3]. However, inflammatory disorders are not well known in patients without MDS, and these patients differ from those with MDS. Furthermore, there is limited experience of treatment of inflammatory conditions in trisomy 8 patients without MDS. In this case report, we describe a trisomy 8 patient without MDS who developed a severe inflammatory disorder with pulmonary infection and responded to methylprednisolone therapy.

A 27-year-old man with recurrent fever, fatigue for more than 2 mo, and unconsciousness for 1 day was admitted to our emergency department.

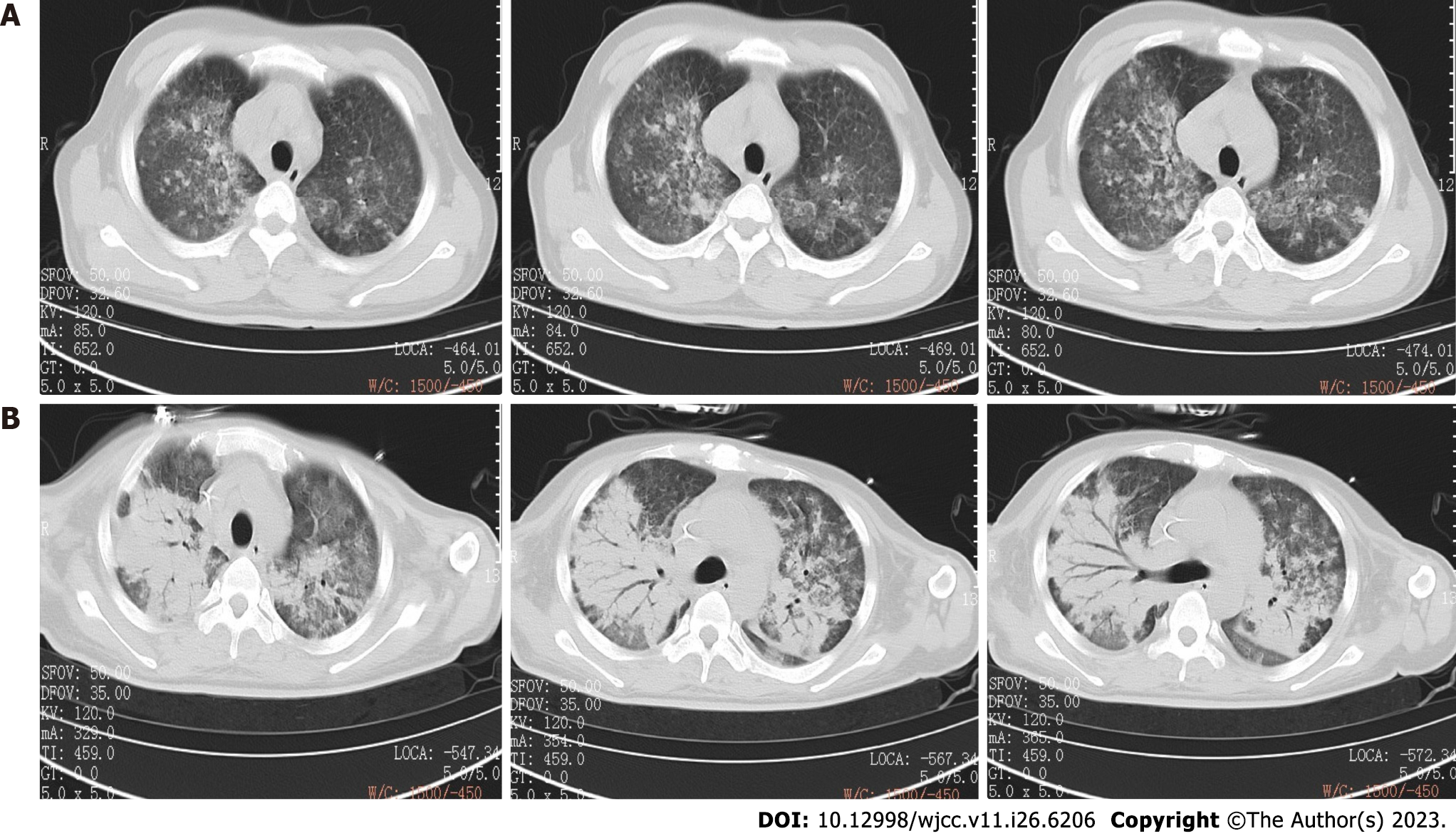

During the previous 2 mo, the patient had visited our outpatient department twice for fever and fatigue, his highest documented temperature having been 40.0°C. A chest computed tomography (CT) 6 wk prior to admission had shown bilateral lung infection (Figure 1A). Routine blood testing revealed the following: White blood cell (WBC) count: 14.63 × 109/L, red blood cell (RBC) count: 3.35 × 1012/L, hemoglobin: 107.00 g/L, platelet count: 98 × 109/L, and C-reactive protein (CRP): 47.63 mg/L. Because the patient refused admission, the attending physician prescribed the antibiotic moxifloxacin (0.4 g daily) and asked him to attend the outpatient department for follow-up.

The patient had no notable history of past illness.

The patient had no notable personal or family history.

The patient’s temperature was 38.5°C, pulse rate 129 beats/min, respiratory rate 42 beats/min, transcutaneous saturation of oxygen 65%, and blood pressure 85/55 mmHg (11.33/7.33 kPa) on admission. His blood pressure increased to 113/78 mmHg (15.029/10.374 kPa) with infusion of 1 µg/kg/min norepinephrine. He was intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation in synchronous intermittent mandatory ventilation mode with the following settings: Fraction of inspired oxygen: 80%, positive end-expiratory pressure: 10 cm H2O, and pressure support: 15 cm H2O. His breathing was shallow with obvious moist crackles. No other abnormalities were detected on physical examination.

Routine blood testing 6 wk before admission revealed a high WBC count [14.63 × 109/L (normal range 3.5–9.5)], high CRP concentration [47.63 mg/L (< 8.0)], low RBC count [3.35 × 1012/L (4.30–5.80)], low hemoglobin [107.00 g/L (130–175)] and low platelet count [98 × 109/L (125–350)], indicating that he had inflammation and was anemic. Blood gas analysis on admission revealed anoxia and hyperventilation with a low partial pressures of oxygen [46.8 mmHg (80–100)] and carbon dioxide [24.3 mmHg (35–45)], pH: 7.516 (7.35–7.45), and transcutaneous oxygen saturation 75%. Routine blood testing on admission revealed a higher WBC count (34.45 × 109/L) and CRP concentration (80.78 mg/L) than 6 wk previously, together with a lower hemoglobin (90.00 g/L) and platelet count (80.78 mg/L) than previously, indicating that his inflammation and anemia had progressed. Additionally, his RBC count was 3.36 × 1012/L, mean corpuscular volume 120.1 fL (82.0–100.0), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin 40.8 pg (27.0–34.0). His erythrocyte sedimentation rate [106 mm/h (0–15)] and ferritin [> 1500.00 ng/mL (15–200)] provided further evidence of inflammation.

Chest CT 6 wk before admission had shown multiple patchy shadows with ill-defined boundaries and local consolidation in both lungs, indicating that he had bilateral pneumonia (Figure 1A). On admission, CT showed more severe multiple patchy shadows in both lungs and consolidation, indicating that his pneumonia had worsened (Figure 1B). B-mode ultrasonography of the liver and spleen on admission showed no obvious abnormalities.

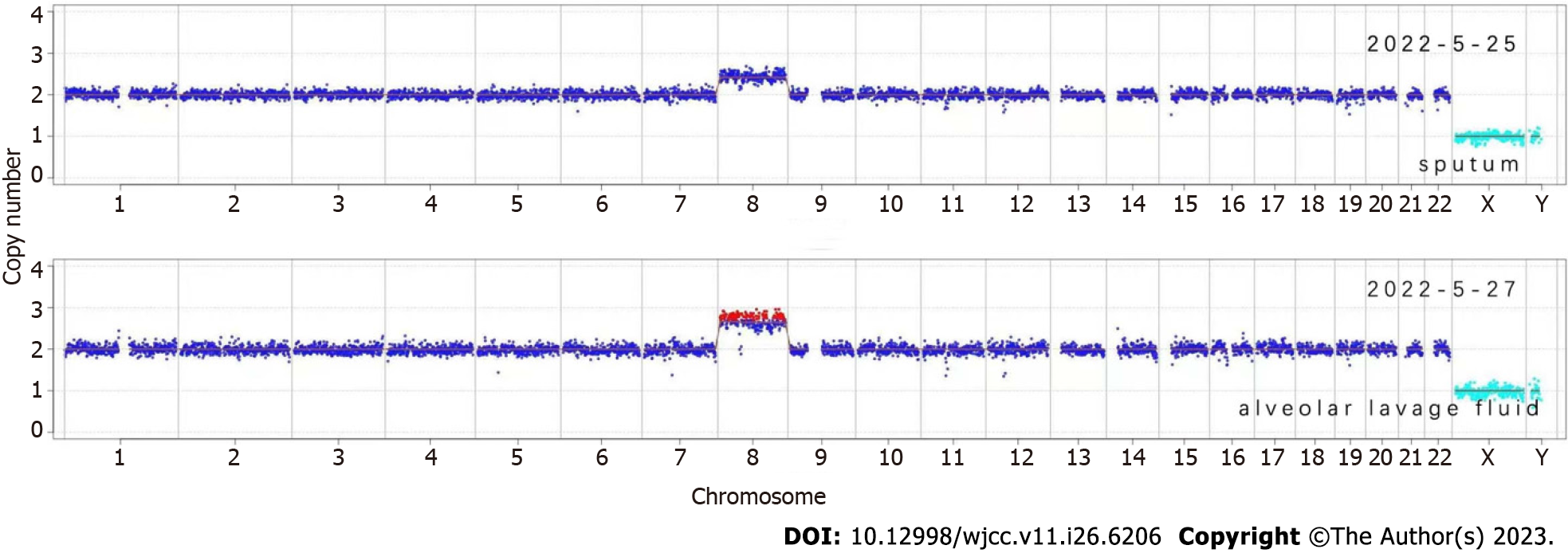

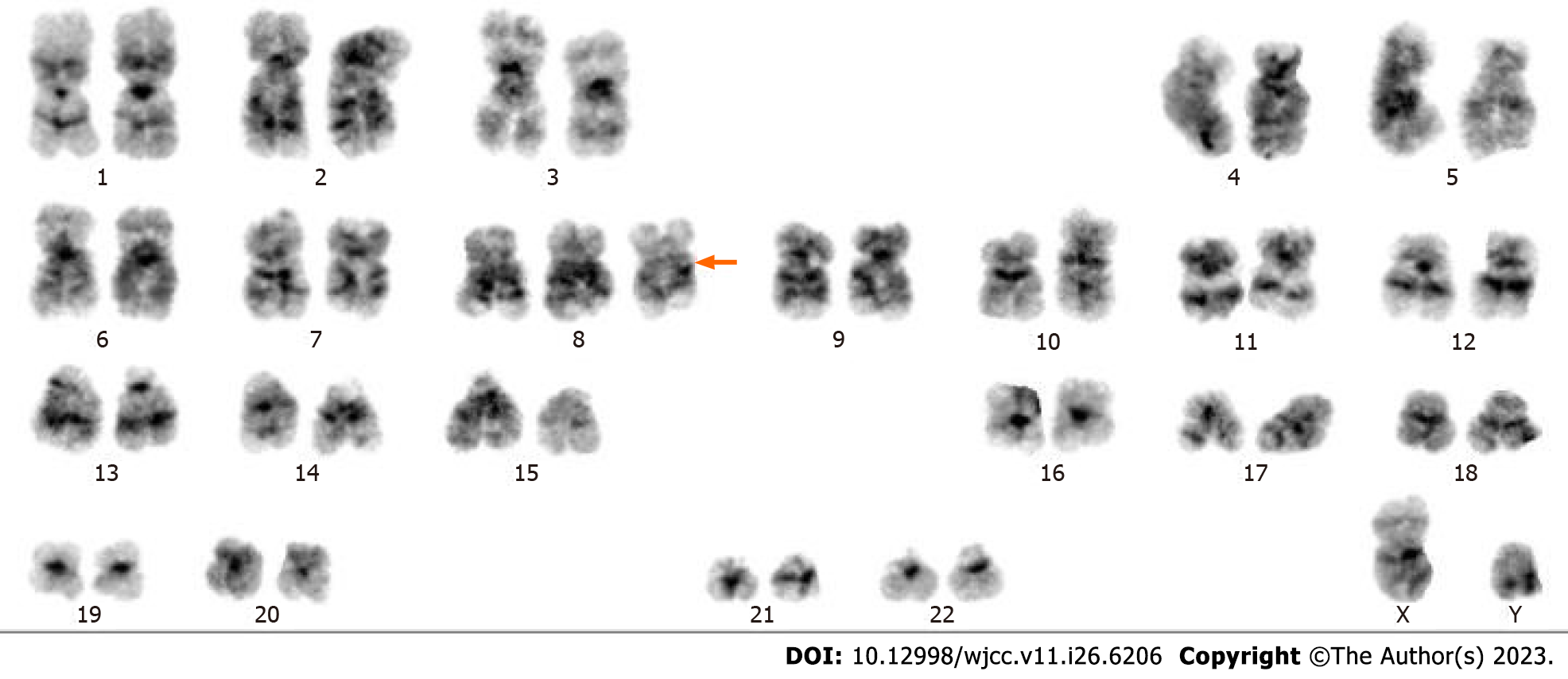

This patient’s initial diagnosis was severe pneumonia. Sputum samples were collected for metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) to identify the causative organism(s). Epstein–Barr virus and Mycobacterium kansasii were detected. Additionally, chromosomal copy number analysis showed duplications on chromosome 8 (Figure 2), indicating the presence of MDS or acute myeloid leukemia. Because the patient’s condition had not improved 2 d later, we collected an alveolar lavage fluid sample for repeat mNGS. Cordyceps portugal and M. kansasii were detected and chromosome 8 duplication confirmed (Figure 2). Suspecting hematological disease, we aspirated bone marrow from the iliac spine, examination of which revealed evidence of infection (Figure 3). Moreover, karyotype analysis again identified trisomy 8 (Figure 4). Immunophenotypic analysis ruled out leukemia. Blood cultures were performed to detect possible pathogenic microorganisms, these yielded Candida Portugal, prompting a change in his therapeutic regimen (described later in the text).

Based on our patient’s medical history, and findings on imaging, blood tests, mNGS, and bone marrow aspiration, both the initial and final diagnoses were severe pneumonia, respiratory failure, septic shock, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and trisomy 8.

In the outpatient department 6 wk prior to admission, the patient received 0.4 g moxifloxacin daily to treat his lung infection. When he was admitted to the emergency department and intubated, the antibacterials imipenem and vancomycin were administered. He was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU), where vancomycin 1 g 12 hly and imipenem 0.5 g 6 hly were administered. He also received ambroxol to reduce mucus, omeprazole to prevent stress-related ulcers, and enteral nutrition. On ICU Day 3, vancomycin was discontinued. On ICU Day 5, we added the antifungal agent fluconazole 0.4 g daily and on ICU Day 7, methylprednisolone 500 mg daily was administered as an anti-inflammatory agent. On ICU Day 10, imipenem was discontinued and piperacillin–tazobactam 4.5 g 8 hly substituted for it. The methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 250 mg daily. On ICU Day 12, the patient was successfully extubated. On ICU Day 13, the methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 120 mg daily, and on ICU Day 16 further reduced to 60 mg daily. On ICU Day 17, the patient was transferred to the Department of Respiratory Medicine, being discharged 5 d later in good clinical condition (Table 1).

| Date | Time | Event |

| 5.24 | 15:00 | Admission to hospital |

| 15:05 | Intubation | |

| 15:30 | Anti-infection | |

| 17:51 | ICU admission | |

| 5.24-5.26 | 23:25-00:00 | Vancomycin 1g q12h, imipenem 0.5g q6h and alveolar lavage fluid for mNGS |

| 5.26 | Second mNGS, blood culture and bone marrow puncture | |

| 5.29 | Fluconazole 0.4 g qd | |

| 5.31 | Methylprednisolone 500 mg qd | |

| 6.3 | Methylprednisolone 250 mg qd and piperacillin-tazobactam 4.5 g q8h | |

| 6.5 | Extubation | |

| 6.6 | Methylprednisolone 120 mg qd | |

| 6.9 | Methylprednisolone 60 mg qd | |

| 6.10 | Transferred to department of respiratory medicine | |

| 6.15 | Discharged |

The patient was transferred to the Department of Respiratory Medicine after a 17-d ICU stay. With the following 5 d of treatment, he met our discharge criteria and was discharged.

Trisomy 8 is consistently associated with MDS[4]. Patients with isolated trisomy 8, that is, without MDS, frequently develop inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, the majority of which involve the gastrointestinal tract[2]. Here, we report a patient with trisomy 8 whose initial presentation was severe pneumonia that responded to glucocorticoid treatment. Our findings are consistent with previous reports that most patients with gastrointestinal involvement respond to glucocorticoid treatment[5].

Auto-inflammation refers to abnormal systematic inflammation mediated by the innate immune system[6,7]. Auto-inflammatory conditions, such as Behçet’s disease, are common in trisomy 8 patients with MDS. However, the mechanism of the association between trisomy 8 and auto-inflammatory conditions is unknown. The term “hemato-inflammatory disease” has been proposed for denoting systemic inflammatory disease caused by somatic mutations in blood cells; these conditions may progress to manifesting as hematopoietic disorders[8-10]. However, not all trisomy 8 patients develop auto-inflammatory manifestations. The full pathophysiological significance of trisomy 8 remains unclear. There have been a few reports of isolated trisomy 8 patients without MDS. These patients characteristically develop macrocytic anemia and mild cytopenia[1]. Clonal hematopoiesis can result in auto-inflammation before it progresses to development of hematological malignancies. In the present patient, it is possible that a chronic excess of pro-inflammatory cytokines (produced and released by innate immune cells) occurred first, and that the stimulus of an infection exacerbated the inflammatory response, ultimately causing a severe inflammatory disorder.

The optimal management of inflammation in isolated trisomy 8 patients without MDS has not yet been determined. Steroids are usually necessary in patients with MDS and associated auto-inflammatory disease, with or without trisomy 8[11]. These agents are used to suppress systemic inflammation; however, the dose and specific form of steroid that are optimal for patients with MDS have not yet been determined[12]. Furthermore, steroids may have adverse effects, such as gastrointestinal bleeding and electrolyte disorders. Thus, it is necessary to determine the optimal treatment regimen while reducing the risks. Importantly, only 30% of MDS patients respond to steroids, most of them requiring steroid-sparing treatment[1]. Moreover, in some patients with gastrointestinal involvement Janus kinase inhibitors, such as tofacitinib, have reportedly enhanced responses to treatment by downregulating the activity of proinflammatory factors[5,13]. However, the efficacy of this therapy requires investigation by well-designed and rigorous studies.

Interleukin-1 signaling may play an important role in the development of auto-inflammatory disorders. Thus, treatments targeting interleukin-1, such as anakinra, canakinumab, and rilonacept, may be effective[14,15]. The only anti-inflammatory therapy used in our case was high doses of methylprednisolone. Fortunately, this suppressed his inflammation and, with effective anti-infective therapy, the patient eventually recovered.

This case report had several limitations. First, steroids should have been introduced earlier. Second the dose of methylprednisolone we used was large, however we did not know whether such a dose was appropriate to this patient, maybe a lower dose also could work.

We have here reported a trisomy 8 patient without MDS who presented with a severe inflammatory disorder accompanied by pulmonary infection. The patient’s illness had auto-inflammatory features and responded to methylprednisolone treatment.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, general and internal

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Masyeni S, Indonesia; Panda CK, India S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Wesner N, Drevon L, Guedon A, Fraison JB, Trad S, Kahn JE, Aouba A, Gillard J, Ponsoye M, Hanslik T, Gourguechon C, Liozon E, Laribi K, Rossignol J, Hermine O, Adès L, Carrat F, Fenaux P, Mekinian A, Fain O; GFM, MINHEMON (French Network of Dysimmune Disorders Associated to Hemopathies). Inflammatory disorders associated with trisomy 8-myelodysplastic syndromes: French retrospective case-control study. Eur J Haematol. 2019;102:63-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liu Z, Yang C, Bai X, Shen K, Qiao L, Wang Q, Yang H, Qian J. Clinical features and prognosis of patients with gastrointestinal Behçet's disease-like syndrome and myelodysplastic syndrome with and without trisomy 8. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2022;55:152039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Koguchi-Yoshioka H, Inokuma D, Kanda M, Kondo M, Kikuchi K, Shimizu S. Behçet's disease-like symptoms associated with myelodysplastic syndrome with trisomy 8: a case report and review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:355-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Esatoglu SN, Hatemi G, Salihoglu A, Hatemi I, Soysal T, Celik AF. A reappraisal of the association between Behçet's disease, myelodysplastic syndrome and the presence of trisomy 8: a systematic literature review. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:S145-S151. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Fu Y, Wu W, Chen Z, Gu L, Wang X, Ye S. Trisomy 8 Associated Clonal Cytopenia Featured With Acquired Auto-Inflammation and Its Response to JAK Inhibitors. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:895965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Masters SL. Broadening the definition of autoinflammation. Semin Immunopathol. 2015;37:311-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pathak S, McDermott MF, Savic S. Autoinflammatory diseases: update on classification diagnosis and management. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Oka S, Ono K, Nohgawa M. The acquisition of trisomy 8 associated with Behçet's-like disease in myelodysplastic syndrome. Leuk Res Rep. 2020;13:100196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huang H, Zhang W, Cai W, Liu J, Wang H, Qin T, Xu Z, Li B, Qu S, Pan L, Huang G, Gale RP, Xiao Z. VEXAS syndrome in myelodysplastic syndrome with autoimmune disorder. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2021;10:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Beck DB, Ferrada MA, Sikora KA, Ombrello AK, Collins JC, Pei W, Balanda N, Ross DL, Ospina Cardona D, Wu Z, Patel B, Manthiram K, Groarke EM, Gutierrez-Rodrigues F, Hoffmann P, Rosenzweig S, Nakabo S, Dillon LW, Hourigan CS, Tsai WL, Gupta S, Carmona-Rivera C, Asmar AJ, Xu L, Oda H, Goodspeed W, Barron KS, Nehrebecky M, Jones A, Laird RS, Deuitch N, Rowczenio D, Rominger E, Wells KV, Lee CR, Wang W, Trick M, Mullikin J, Wigerblad G, Brooks S, Dell'Orso S, Deng Z, Chae JJ, Dulau-Florea A, Malicdan MCV, Novacic D, Colbert RA, Kaplan MJ, Gadina M, Savic S, Lachmann HJ, Abu-Asab M, Solomon BD, Retterer K, Gahl WA, Burgess SM, Aksentijevich I, Young NS, Calvo KR, Werner A, Kastner DL, Grayson PC. Somatic Mutations in UBA1 and Severe Adult-Onset Autoinflammatory Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2628-2638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 739] [Article Influence: 147.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Montoro J, Gallur L, Merchán B, Molero A, Roldán E, Martínez-Valle F, Villacampa G, Navarrete M, Ortega M, Castellví J, Saumell S, Bobillo S, Bosch F, Valcárcel D. Autoimmune disorders are common in myelodysplastic syndrome patients and confer an adverse impact on outcomes. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:1349-1356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ozen S, Bilginer Y. A clinical guide to autoinflammatory diseases: familial Mediterranean fever and next-of-kin. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10:135-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hoffman HM, Broderick L. JAK inhibitors in autoinflammation. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:2760-2762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Krainer J, Siebenhandl S, Weinhäusel A. Systemic autoinflammatory diseases. J Autoimmun. 2020;109:102421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Havnaer A, Han G. Autoinflammatory Disorders: A Review and Update on Pathogenesis and Treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:539-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |