Published online Sep 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i26.6189

Peer-review started: April 28, 2023

First decision: July 3, 2023

Revised: July 16, 2023

Accepted: August 17, 2023

Article in press: August 17, 2023

Published online: September 16, 2023

Processing time: 133 Days and 2.2 Hours

Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) is an independent disease characterized by edematous optic discs. In eyes with branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO), the arteries and veins in the ethmoid plate of the optic disc are relatively crowded; however, a combination of the two is clinically uncommon. Herein, we reported a patient with NAION and concealed BRVO, for which the treatment and prognosis were not similar to those for NAION alone.

Herein, we report a case of NAION with concealed BRVO that did not improve with oral medication. A week later, we switched to intravenous drug administration to improve circulation, and the patient’s visual acuity and visual field recovered. Hormonal therapy was not administered throughout the study. This case suggested that: (1) Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) can help detect hidden BRVO along with the NAION diagnosis; (2) intravenous infusion of drugs to improve circulation has positive effects in treating such patients; and (3) NAION with concealed BRVO may not require systemic hormonal therapy, in contrast with the known treatment for simple NAION.

NAION may be associated with hidden BRVO, which can only be observed on FFA; intravenous therapy has proven effectiveness.

Core Tip: Herein, we report a case of non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) complicated by concealed branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO). Visual function recovered following an intravenous drip of circulatory drugs. This suggests that: (1) Fundus fluorescein angiography can help detect hidden BRVO; (2) the intravenous administration of drugs to improve circulation has positive effects in such patients; and (3) these patients may not require systemic hormonal therapy. These concepts differ from the concepts adopted regarding the treatment and prognosis of the previously reported simple NAION.

- Citation: Gong HX, Xie SY. Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy combined with branch retinal vein obstruction: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(26): 6189-6193

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i26/6189.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i26.6189

Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) is a prevalent eye condition in individuals aged > 50 years. It is characterized by reduced visual acuity and visual field defects associated with physiological blind spots[1-4]. NAION is an independent disease that occurs frequently in older patients with chronic atherosclerotic lesions. Optic disc crowding is a distinctive characteristic of patients with NAION[5]. Moreover, branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) occurs as a result of the obstruction of blood flow return caused by intraretinal thrombosis, chronic inflammatory response, or vascular endothelial cell proliferation. In affected eyes, the retinal arteries and veins are typically crowded at the optic disc sieve[6]. Epidemiological studies have identified hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis as risk factors for BRVO and for NAION. Patients with NAION combined with BRVO have clinical features that differ from those of patients with NAION alone. We encountered a patient with NAION combined with occult BRVO, whose final vision and visual field were restored.

A woman aged 62 years visited our clinic with a sudden onset of vision loss and a blockage sensation in the left eye in the morning.

The patient experienced a decrease in vision with an obstruction sensation for 1 d, without eye pain or rotational pain.

She had a medical history of hypertension but denied any history of other systemic diseases.

Her visual acuity was 0.8 and 0.2 in the right and left eye, respectively, with an intraocular pressure of 12.6 mmHg and 13.2 mmHg, respectively. On clinical ophthalmological examination of the left eye, the anterior segment was normal, with a relative afferent pupillary defect (+). Localized edema above the optic disc was light in color, with a clear and reddish lower boundary, and the foveolar reflex was absent.

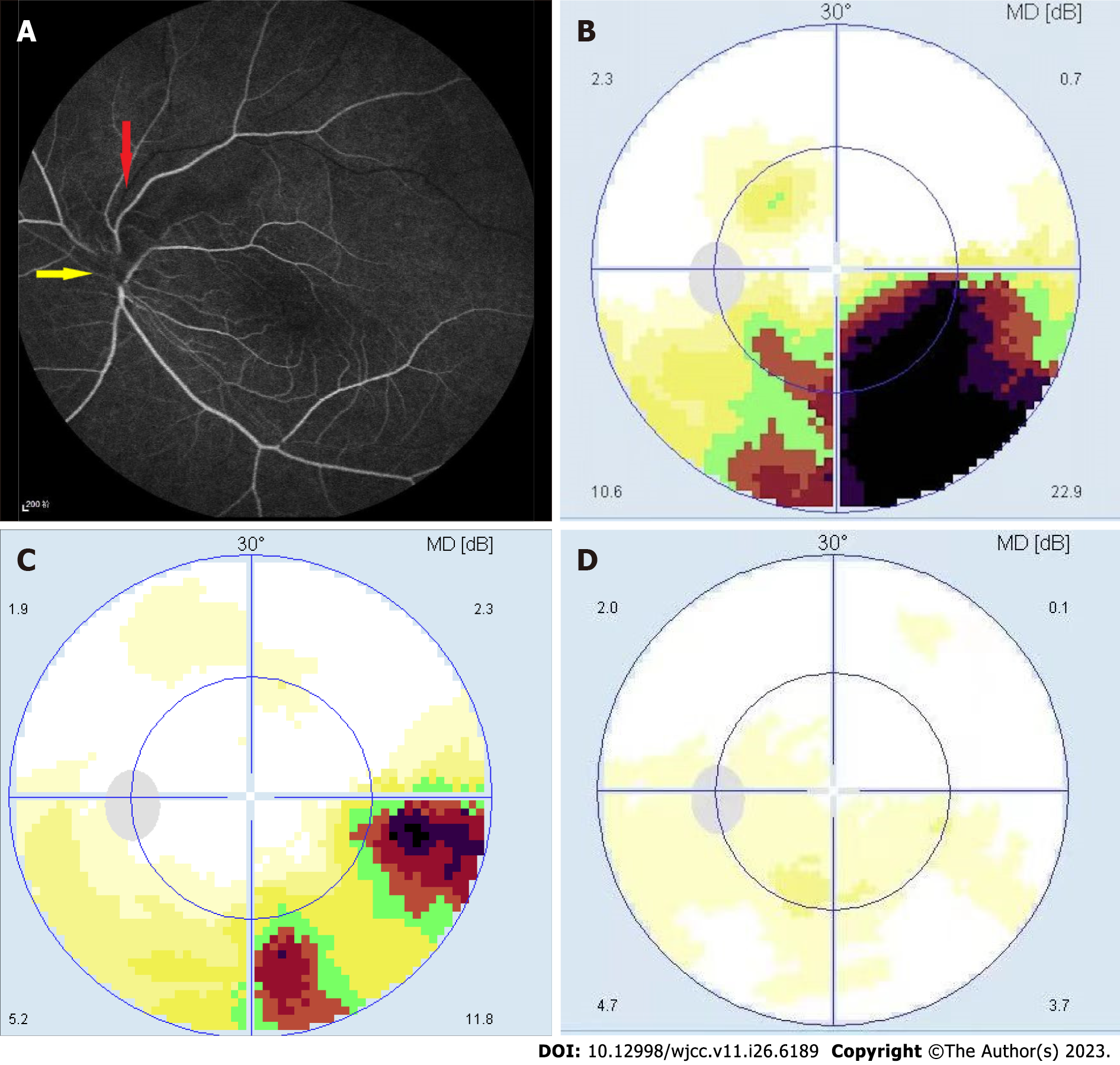

Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) of the left eye revealed early hypofluorescence over the optic disc, with unfilled superior temporal branch veins at 18.12". Moreover, laminar flow was visible in the other branch veins (Figure 1A). Visual field examination revealed an inferior temporal fan-shaped defect in the left eye (Figure 1B).

NAION combined with branch retinal vein obstruction.

The patient received a week of oral treatment with nerve-nourishing and circulation-improving drugs. This was followed by an intravenous drip of nerve-nourishing and circulation-improving drugs [we injected ginkgo leaf extract (5 mL: 17.5 mg; Yuekang Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd., GYZZ H20070226) 15 mL, diluted with 0.9% sodium chloride solution for 250 mL, intravenous drip; the dosage was fixed] for 3 wk.

After a week of oral treatment with nerve-nourishing and circulation-improving drugs, no significant improvement was observed. However, after the intravenous drip of nerve-nourishing and circulation-improving drugs for 2 wk, edema in the upper optic disc was reduced, the color was lighter, visual acuity improved to 0.5, and the visual field also improved (Figure 1C). With the continuation of intravenous treatment for 1 wk, the visual acuity improved to 0.8, the boundary of the optic disc became clear, and the color of the upper optic disc became pale. Additionally, the visual field was restored (Figure 1D).

NAION is a significant cause of vision loss in individuals aged > 50 years. Current evidence states that this condition occurs due to poor perfusion of the optic disc caused by structural and blood flow abnormalities[7,8]. It is a typically isolated event in adults and frequently occurs in older patients with chronic atherosclerotic lesions. Crowding of the optic disc is believed to be a characteristic of NAION[5]. Moreover, BRVO impairs blood return owing to intraretinal thrombosis, chronic inflammatory reactions, or vascular endothelial cell proliferation. Typically, in the affected eye, the retinal arteries and veins are relatively crowded at the sieve plate of the optic disc[6]. Hypertension and a hypercoagulable blood state have been identified as risk factors for BRVO, as for NAION. Optic disc perfusion is usually constant, and the terminal perfusion of the optic nerve is particularly vulnerable. Retinal blood flow resistance affects perfusion pressure, and drugs such as vasospasms or antihypertensives may destroy the automatic regulatory mechanism of the optic disc[5,9]. Therefore, it is speculated that the hypercoagulable state of blood, decreased diastolic function of branch veins, and crowded optic discs may lead to blood flow disorders at the optic disc, resulting in the occurrence of hidden BRVO followed by NAION. One hypothesis suggests that the retinal vein originates from the optic nerve capillaries and flows into the central retinal vein; thus, its obstruction can cause venous insufficiency[10]. NAION may result from optic disc edema triggered by venous insufficiency. Studies have shown that NAION, which is almost a moderate nerve injury caused by venous diseases, differs from inflammatory anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, which is similar to the severe nerve injury caused by arterial cerebral infarction. Furthermore, pathophysiological evidence suggests that the etiology of NAION may be venous in origin[11]; thus, BRVO contributes to the occurrence of NAION. Another hypothesis states that various conditions affecting the optic nerve lead to retinal vein occlusion and that BRVO is a secondary phenomenon. Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) associated with brain pseudo-tumors is caused by an increased intracranial pressure, which directly compresses the optic nerve and blood vessels through the intravaginal optic nerve space, communicating with the subarachnoid space. CRVO associated with neuritis and optic gliomas is caused by a mechanical obstruction. Similarly, in our case report, compression of the swollen optic nerve might have led to BRVO[8]. Further studies are required to elucidate these underlying mechanisms.

Occult BRVO is defined as a prominent retinal vein rupture or hemorrhage that is not observed on fundus examination. However, on FFA, delayed branch retinal vein filling, in comparison with that in the other branch veins, was noted, which corresponded to areas of optic disc edema. Although FFA is not essential for diagnosing NAION, we recommend performing it along with NAION examination, as FFA is typical for most of NAION cases, showing localized hypofluorescence of the optic disc in the early stages and segmental hyperfluorescence of the optic disc in the middle and late stages. Moreover, FFA aids in the detection of occult retinal vascular lesions and facilitates differential diagnosis.

It is widely accepted that corticosteroid administration may benefit patients with NAION[12], as it reduces optic disc edema, thus minimizing secondary damage to the optic nerve owing to edema compression. For our patient, we did not administer hormones, and recovery of the visual field at the end of treatment may suggest the presence of NAION combined with occult retinal branch vein obstruction, where visual impairment was not primarily caused by the mechanical effect of the crowded optic disc. Van et al[13] reported a case of NAION combined with central retinal vein obstruction, in which optic disc edema was further exacerbated after the administration of intravenous steroids, indicating that the increased disc swelling might have resulted from the procoagulant effect of systemic steroid therapy. Similarly, in patients with NAION combined with occult BRVO, early aggressive intravenous circulatory therapy without hormonal therapy may be beneficial for improving perfusion and achieving a good prognosis. Additionally, controlling systemic risk factors remains a significant concern in patients with NAION combined with occult BRVO.

Herein, we present the rare case of an elderly woman with NAION combined with occult BRVO. The patient’s vision and visual field eventually recovered. This case highlights the necessity of performing FFA to detect occult BRVO and that a favorable prognosis may be achieved following intravenous treatment, which improves circulation.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lee KS, South Korea; Morya AK, India; Sotelo J, Mexico S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Han M, Zhao C, Han QH, Xie S, Li Y. Change of Retinal Nerve Layer Thickness in Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Revealed by Fourier Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. Curr Eye Res. 2016;41:1076-1081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Morrow MJ. Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019;25:1215-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Khalili MR, Bremner F, Tabrizi R, Bashi A. Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCT angiography) in anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2023;33:530-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mohammed-Brahim N, Clavel G, Charbonneau F, Duron L, Picard H, Zuber K, Savatovsky J, Lecler A. Three Tesla 3D High-Resolution Vessel Wall MRI of the Orbit may Differentiate Arteritic From Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. Invest Radiol. 2019;54:712-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Di Zazzo G, Guzzo I, De Galasso L, Fortunato M, Leozappa G, Peruzzi L, Vidal E, Corrado C, Verrina E, Picca S, Emma F. Anterior ischemic optical neuropathy in children on chronic peritoneal dialysis: report of 7 cases. Perit Dial Int. 2015;35:135-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fekrat S, Finkelstein D. Current concepts in the management of central retinal vein occlusion. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1997;8:50-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Basile C, Addabbo G, Montanaro A. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and dialysis: role of hypotension and anemia. J Nephrol. 2001;14:420-423. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Abu el-Asrar AM, al Rashaed SA, Abdel Gader AG. Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy associated with central retinal vein occlusion. Eye (Lond). 2000;14 (Pt 4):560-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bordas M, Tabacaru B, Stanca TH. Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy - Case report. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2018;62:231-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Levin LA, Danesh-Meyer HV. Hypothesis: a venous etiology for nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1582-1585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tesser RA, Niendorf ER, Levin LA. The morphology of an infarct in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:2031-2035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB. Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: role of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:1029-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | van Zaane B, Nur E, Squizzato A, Gerdes VE, Büller HR, Dekkers OM, Brandjes DP. Systematic review on the effect of glucocorticoid use on procoagulant, anti-coagulant and fibrinolytic factors. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2483-2493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |