Published online Aug 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i23.5559

Peer-review started: May 10, 2023

First decision: June 19, 2023

Revised: July 2, 2023

Accepted: July 21, 2023

Article in press: July 21, 2023

Published online: August 16, 2023

Processing time: 97 Days and 15.8 Hours

In the past 3 years, the global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has posed a great threat to human life and safety. Among the causes of death in COVID-19 patients, combined or secondary bacterial infection is an important factor. As a special group, pregnant women experience varying degrees of change in their immune status, cardiopulmonary function, and anatomical structure during pregnancy, which puts them at higher risk of contracting COVID-19. COVID-19 infection during pregnancy is associated with increased adverse events such as hospitalisation, admission to the intensive care unit, and mechanical ventilation. Therefore, pregnancy combined with coinfection of COVID-19 and bacteria often leads to critical respiratory failure, posing severe challenges in the diagnosis and treatment process.

We report a case of COVID-19 complicated with Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) coinfection in a pre

The coinfection of pregnancy with COVID-19 and bacteria often leads to critical respiratory failure, which is a great challenge in the process of diagnosis and treatment. It is crucial to choose the right time to deliver the foetus and to quickly find pathogens by mNGS.

Core Tip: Since 2020, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been rapidly spreading worldwide, posing a great threat to the lives of the global population. Approximately 10% to 15% of COVID-19 patients have combined or secondary bacterial infection, and the most common coinfected bacteria are streptococcus pneumoniae (79%). COVID-19 infection during pregnancy is associated with increased adverse events such as hospitalisation, intensive care unit admission, and mechanical ventilation. In this paper, we report a severe case of a 34-wk pregnant woman who was coinfected with COVID-19 and Staphylococcus aureus, leading to respiratory failure.

- Citation: Zhou S, Liu MH, Deng XP. Critical respiratory failure due to pregnancy complicated by COVID-19 and bacterial coinfection: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(23): 5559-5566

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i23/5559.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i23.5559

Since 2020, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has infected more than 600 million people, causing approximately 6 million people to die and posing a great threat to the lives of the global population. Combined or secondary bacterial infection is an important cause of death in COVID-19 patients, with a mortality rate as high as 50%[1]. Current evidence-based medical evidence indicates that approximately 10% to 15% of COVID-19 patients will have combined or secondary bacterial infection, and the most common coinfected bacteria are streptococcus pneumoniae (79%), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (6.8%), and haemophilus influenzae (6.8%). Pregnant women, as a special group, have different degrees of change in their immune status, cardiopulmonary function, and anatomy, making them more vulnerable to COVID-19 infection than nonpregnant women[2]. COVID-19 infection during pregnancy is associated with increased adverse events such as hospitalisation, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and mechanical ventilation. Therefore, the coinfection of pregnancy combined with COVID-19 and bacteria often leads to critical respiratory failure, which presents a great challenge in the diagnosis and treatment process.

A 35-year-old pregnant woman who was 34 + 4 wk past her menstrual period presented with fever and cough for 10 d, followed by aggravated dyspnoea for 5 d.

After her last menstrual period, the patients’ urine pregnancy test was positive for more than 40 d. The pregnancy was through natural conception. This pregnant woman was conscious of foetal movement after 16 wk of pregnancy, and the foetus had been active until the patient presented to the hospital. Ten days prior, the patient had recurrent fever with the highest body temperature being 39.2 ℃, which decreased to normal after oral acetaminophen, and was accompanied by cough, yellow viscous sputum, chest distress and shortness of breath, without chills. Five days prior, the above symptoms worsened with dyspnoea, and she was admitted to our hospital for further diagnosis and treatment.

There was no significant medical history.

There was no significant personal or family history.

A body temperature of 36.4 ℃, blood pressure of 117/87 mmHg, heart rate of 130 beats/min, and respiratory rate of 20 times/min were noted. Cyanosis of the lip could be seen, and thick breathing sounds in both lungs, as well as dry and wet rales in the right lower lung, could be heard. The heart rate was regular, and no noises were heard in the auscultation area of each valve. The gestational and symmetric abdominal type could be seen. Specialist inspection revealed a height of 166 cm, pre-pregnancy weight of 46.5 kg, body mass index of 16.87, and a weight gain of 8.8 kg during pregnancy. The uterine height was 34 cm, the abdominal circumference was 89 cm, contractions were sporadic and weak, there was a head presentation, the foetal heart sounds were 142 beats/min, and the intrapelvic and extrapelvic measurements were normal. The remaining physical examinations showed no significant abnormalities.

The results of arterial blood gas analyses were as follows: pH 7.472, partial pressure of carbon dioxide 34.0 mmHg, partial pressure of oxygen 56 mmHg, sulfur dioxide 88.6%; C-reactive protein (CRP): 186.33 mg/L (normal range ≤ 0.8 mg/L); erythrocyte sedimentation rate: 69.00 mm/h (normal range ≤ 20 mm/h); procalcitonin (PCT): 2.24 ng/mL (normal range ≤ 0.5 mm/h); routine blood test: White blood cell (WBC) 18.29 × 109/L, neutrophil % 90.10%, lymphocyte 0.97 × 109/L; biochemical test: Alkaline phosphatase 232 U/L, total bilirubin 23.1 μmol/L, albumin (ALB) 33.9 g/L, K+ 2.93 mmol/L, sodium 129 mmol/L, chloride 89 mmol/L; cardiac markers were normal: D-dimer 3.50 mg/L.

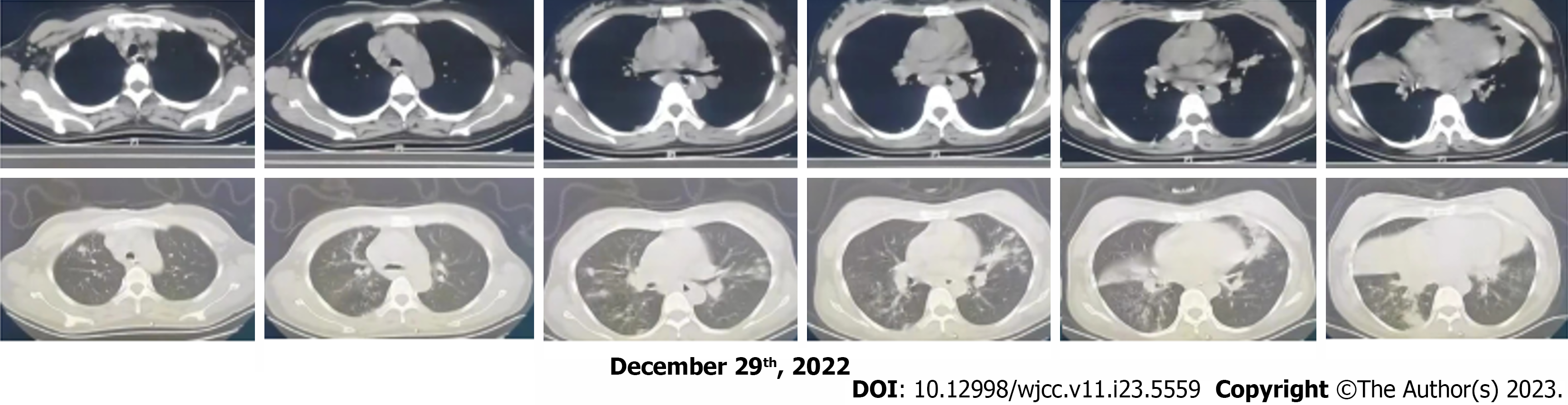

Chest computed tomography (CT) showed multiple plaques, miliary foci, nodular foci with partial consolidation and cavities in the upper and lower lobes of both lungs (Figure 1). Obstetric ultrasound showed a single viable foetus, head presentation, and oligohydramnios. Cardiac ultrasound and lower extremity vascular ultrasound showed no significant abnormalities.

History of menstruation. The patient had her first menarche at the age of 15. Her menstrual cycle was regular, lasting for 3-4 d every 30 d. The last menstruation occurred on May 2, 2022, with a moderate menstrual volume and a normal colour. There were no blood clots or painful menstruation. History of marriage and childbearing. The patient married at an appropriate age, and her spouse was healthy. She had one pregnancy history, G2P1, with a full-term normal delivery of a female infant in 2006, weighing 3500 g and in good health.

(1) Pregnancy combined with severe pneumonia novel coronavirus infection S. aureus infection type respiratory failure; (2) late pregnancy with 34 + 4 wk G2P1 left occiput anterior; (3) elderly second parturient women; (4) maternal lower weight; (5) oligohydramnion; (6) premature live baby; (7) electrolyte disturbance; and (8) hypoproteinaemia.

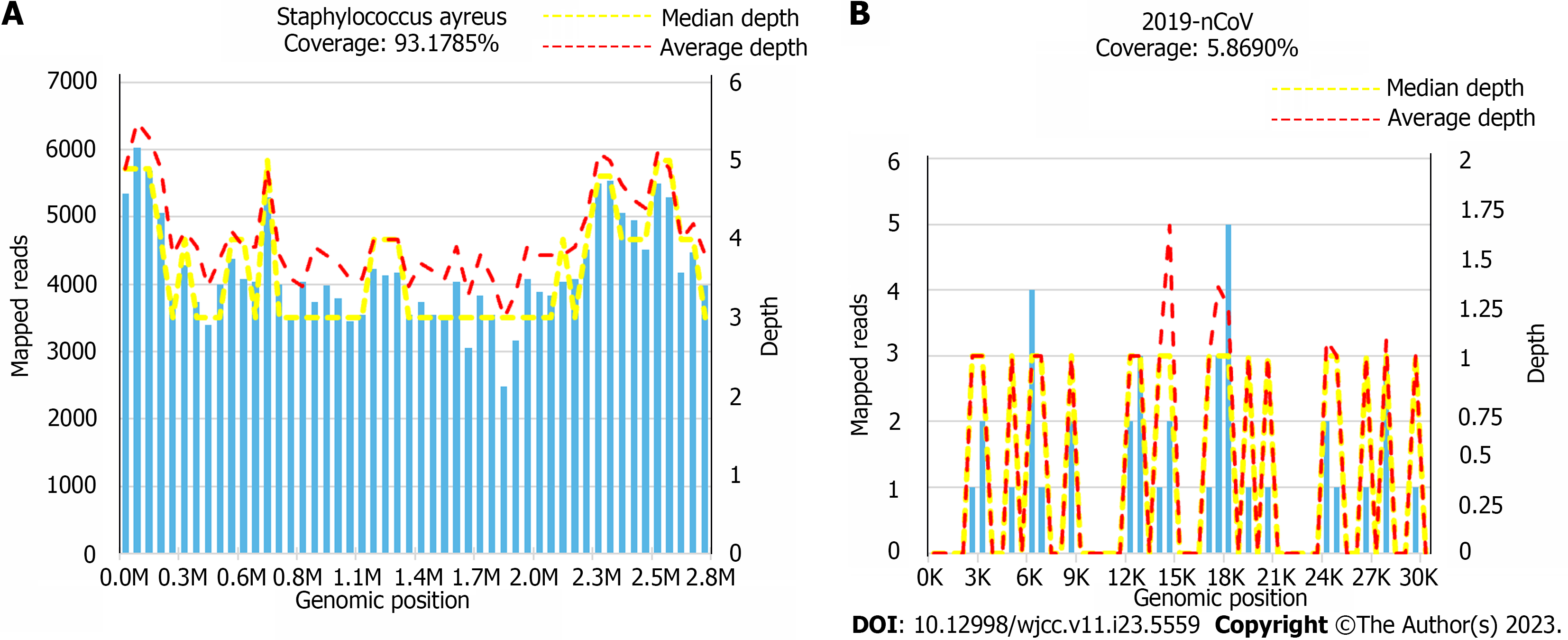

Combined with the clinical manifestations and auxiliary examinations, we considered that the patient might have tuberculosis and a severe bacterial infection. Therefore, we temporarily administered cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium for anti-infective therapy and 10 mg dexamethasone to promote foetal lung maturation. Under oxygen-uptaking conditions, her oxyhemoglobin saturation continued to progressively decline, and the foetal heart sounds were 146 beats/min, which would result in foetal distress and a dead foetus in the uterus. We planned to perform a caesarean section of the lower uterus. However, we changed the mask oxygen inhalation to high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy, with parameters of fraction of inspired oxygen at 100% and a flow rate of 50 L/min. The patients’ cyanosis improved significantly and her oxyhemoglobin saturation increased to 95%-98%. Therefore, her oxyhemoglobin saturation was measured on the 2nd day. After delivery, the foetus was transferred to the neonatal ICU, and the puerperant woman was transferred to the respiratory ICU. She was given assisted ventilation by endotracheal intubation with a ventilator, empirical antibiotic therapy to prevent infection by intravenous drip of meropenem and vancomycin, and symptomatic treatment of fluid and ALB infusion. The irrigation solution was collected and tested for metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) by bedside tracheoscopy, which showed S. aureus combined with novel coronavirus infection (Figure 2, Tables 1-3). At the same time, there were no acid-fast bacilli in the sputum tuberculosis smear, tubercle bacillus-polymerase chain reaction (TB-PCR) and nontuberculosis mycobacterium-PCR were negative, and galactomannan experiments were normal. Therefore, evidence for tuberculosis infection was insufficient. Continued intravenous drip of 1 g every 12 h (q12h) vancomycin and 1 g q8h meropenem, anticoagulant therapy, treatments to relieve the cough and reduce the amount of sputum, and other symptomatic treatment were given. On the 2nd day after surgery, the treatment transitioned from assisted ventilation by the invasive ventilator to nasal tube oxygen with a flow rate of 3-4 L/min. On the 4th day after surgery, chest CT showed multiple areas of inflammation in both lungs, mildly enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes and a small amount of bilateral pleural effusion (Table 1). CRP was 38.54 mg/L, WBC count was 8.25 × 109/L, PCT was 0.129 ng/mL, potassium was 4.04 mmol/L, D-dimer was 2.44 mg/L, and TB-PCR was negative. On the 9th day after surgery, chest CT showed inflammatory lesions, and the pleural effusion had been absorbed compared with the findings on January 4, 2023 (Figure 3). Antibiotics were adjusted to sitafloxacin 50 mg twice daily. On the 11th day after surgery, the patients’ condition was stable (Table 1), and she was discharged from the hospital without special treatment.

| Name | Sequence number | Drug resistance type | Corresponding species | Association confidence | Drug resistance |

| ErmB | 135 | Macrolides lincosamides | Staphylococcus aureus | > 95% | Erythrocin lincomycin |

| ErmC | 274 | Macrolides lincosamides | Staphylococcus aureus | > 95% | Erythrocin lincomycin |

| Type | Genus | Species | ||

| Name | Sequence number | Name | Sequence number | |

| G+ | Staphylococcus | 57646 | Staphylococcus aureus | 43700 |

| Type | Name | Sequence number |

| RNA virus | 2019-nCoV | 10 |

One week after discharge, chest CT showed that the multiple lung inflammation was absorbed slightly compared with the findings on January 10, 2023; at 1 mo later, chest CT showed that the multiple lung inflammation was apparently absorbed compared with the findings on January 18, 2023 (Figure 1). The results of mNGS showed that the sequence number of S. aureus was 43700 and the coverage of S. aureus was 93.1785%. The sequence number of 2019-nCoV was 10, and the coverage of 2019-nCoV was 5.8690%. Therefore, the main pathogens that caused serious pneumonia in this pregnant woman were the new coronavirus combined with S. aureus infection (Figure 2, Tables 1-3). The bacterial resistance gene test results show that S. aureus was resistant to both macrolide and lincosamide antibiotics (Table 1). Chest CT showed that the inflammatory lesions of the patients’ lungs were gradually absorbed and improved (Figure 3).

COVID-19 caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been rapidly spreading around the world since its emergence and is mainly transmitted by droplets and contact, leading to its strong infectivity and fast propagation speed. After people become infected with SARS-CoV-2, the S-spike protein binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 on the alveolar epithelial cell surface by mediating transmembrane serine protease 2[3], viral pneumonia occurs, and a hyperinflammatory syndrome or “cytokine storm” may develop, further leading to many complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), thromboembolic events, septic shock, and multiple organ failure. Virologists assumed[1] that the virus attaches to and penetrates the hosts’ airway epithelial cells, leading to cellular dysfunction and apoptosis via many mechanisms; weakens the hosts’ immune system, contributing to the proliferation, colonisation and invasive infection of opportunistic pathogens or normal respiratory flora; obstructs the innate immune response; compresses the airway mucus; and destroys the cilia, promoting virus transmission and adhesion. Finally, viruses and bacteria act synergistically to aggravate the clinical outcome. Therefore, combined or secondary bacterial infections are common complications of many viral respiratory infections and are closely related to an increased risk of shock, respiratory failure, prolonged ICU stay and increased mortality. Studies have shown that combined or secondary infections at the time of admission are most common in COVID-19 patients, with St. pneumoniae, S. aureus, and H. influenzae being the most common[1,4]. A retrospective study reported[5] that of 1251 samples, 66 (5.52%) showed secondary bacterial infections in patients with COVID-19, with S. aureus being a common pathogen (24.3%). Based on this case, we mainly discussed the coinfection of COVID-19 and S. aureus in pregnancy.

During pregnancy, significant changes in the physiological status of the respiratory, cardiovascular, coagulation, and endocrine and immune systems can lead to increased susceptibility and increased morbidity and mortality of infection with COVID-19. A study showed that compared to nonpregnant women, many women during pregnancy are asymptomatic or have only mild symptoms, but severe COVID-19 infection is closely related to caesarean delivery, premature birth, ICU occupancy, and invasive ventilation[6]. The management of ARDS in a pregnant woman is challenging because of the physiological changes in pregnancy and the detrimental effects of hypoxemia and hypercarbia on the foetus[7]. Common clinical manifestations of pregnancy with combined COVID-19 include cough, headache, myodynia, fever, sore throat, shortness of breath, and loss of taste or smell[8]. Laboratory tests can show increased CRP, WBC, PCT, decreased lymphocytes, and abnormal liver enzymes, and iconography may present as ground-glass opacity, posterior pulmonary involvement, multilobular involvement, bilateral pulmonary involvement, peripheral distribution, and consolidation[9]. The diagnosis can be made by combining the clinical manifestations, laboratory examination, imaging findings, and COVID-19 nucleic acid virus testing. Reviewing the relevant literature[10], low molecular weight heparin anticoagulant therapy can be used to prevent thromboembolism because pregnant women with COVID-19 are at higher risk of thromboembolic events. Glucocorticoids can be used to resist infection and promote foetal lung maturation. Acetaminophen is considered safe for pregnant women with fever. However, there is limited research on the safety of antiviral drugs and interleukin 6 inhibitors for pregnant women and foetuses, and they should be used with caution. In this discussed case, the pregnant woman developed respiratory failure due to severe infection. At the same time, hormonal changes, immune function changes, mechanical effects of uterine enlargement, and increased foetal-placental unit metabolic requirements can further increase the risk of hypoxia in pregnant women, which will cause uterine artery contraction and foetal-placental vasoconstriction, reduce placental blood supply, and reduce foetal oxygen supply, leading to serious consequences such as foetal distress and a dead foetus in utero[11]. Therefore, it is crucial to choose the appropriate time for caesarean section. The literature suggests that for patients with intractable hypoxemia after 32 wk of pregnancy or in cases of worsening or persistent critical condition, delivery should be considered[12]. However, if the gestational age is less than 24 wk and the mothers’ cardiopulmonary function is unstable, delivery should be delayed, and the treatment plan should prioritise maternal safety. In consideration of the continuous hypoxia in the pregnant woman, timely caesarean section was performed, and the patients’ respiratory failure was quickly corrected. The patient and newborn were safely discharged after multidisciplinary collaborative treatment in obstetric, neonatology and respiratory medicine.

S. aureus infection is common in patients with immune dysfunction, ICU admission, chronic disease, and viral infections. The onset of the disease is abrupt, and the disease progresses rapidly, leading to septic shock, multiple organ failure and a high mortality rate in a short period of time. Chest CT may show ground glass shadow, multiple nodules, and clumpy high-density shadow, as well as signs of cavities, air sac or pleural effusion, which is mainly related to the release of toxins and invasive enzymes by S. aureus leading to lung tissue necrosis. Treatment includes semisynthetic penicillins or cephalosporins that are resistant to penicillinase, and vancomycin should be used to treat methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections. S. aureus infection is a known complication of the virus epidemic, and with the prevalence of COVID-19, related studies on patients with combined S. aureus infection have been reported. Among 115 COVID-19 patients with S. aureus infection, 71 patients (61.7%) died, 62 patients (53.9%) required admission to the ICU, and 41 patients (35.7%) were discharged, indicating significantly higher mortality compared to patients with only COVID-19 infection[13]. This case shows special imaging manifestation of S. aureus pneumonia combined with COVID-19, with ground-glass opacities, multiple nodular shadows and ground-glass opacities, accompanied by cavities, which did not conform to the typical imaging manifestation of COVID-19 and tended to resemble tuberculosis. This interferes with the doctors’ diagnosis and treatment process and requires doctors to have rich clinical experience and medical knowledge with auxiliary examinations to make accurate judgements and provide timely treatment to improve prognosis.

Traditional microbial diagnostic methods include specimen culture, immunological testing, PCR/gene chip, and mass spectrometry, and these methods have limitations such as prehypothesis, low positive rate, long testing cycle, and difficulty in detecting special pathogens. In recent years, emerging mNGS has been used to detect a variety of pathogens by sequencing microbial and host nucleic acids in clinical samples. MNGS has been widely used in the detection of special pathogens due to its unique advantages of unbiased detection, rapid authentication, comprehensive coverage, no need for preconceived assumptions and no need for cultivation. It can be used in various sample types, including blood, cerebrospinal fluid, respiratory tract samples, and gastrointestinal fluid. The use of mNGS to identify SARS-CoV-2 was successfully achieved on January 2, 2020, by sequencing RNA extracted from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of 2 patients who had experienced severe pneumonia in Wuhan, China[14]. In addition, mNGS analysis of BALF samples from 5 patients with similar symptoms of ARDS in the same region showed that all 5 patients had SARS-CoV-2, and the nucleotide homology in the viral isolates was 99.8%[15]. This technology has made significant progress in detecting the new coronavirus. However, there are few reports on the application of mNGS in detecting COVID-19 combined with bacterial infection. This article describes the successful application of mNGS in the rapid detection of the pathogen causing severe pneumonia in a pregnant woman, which led to targeted antimicrobial therapy and saved the woman’s life. The whole process, from sample collection to obtaining results, took only 17 h, which allowed time for the rescue of the critically ill pregnant woman, demonstrating the significant advantages of mNGS in evidence-based treatment. It can be used in the early and rapid diagnosis of mixed bacterial infections and drug sensitivity testing, particularly in cases of infection with multidrug-resistant bacteria, to guide the adjustment of antibiotic treatment and save patients’ lives.

In this paper, we report a severe case of a 34-wk pregnant woman who was coinfected with COVID-19 and S. aureus, leading to respiratory failure. The patients’ condition improved, and she was discharged after undergoing timely caesarean section surgery and receiving targeted treatment based on pathogen identification through mNGS testing after the operation. This case provides referential value for the treatment of critically ill COVID-19 patients in clinical practice.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nasa P, United Arab Emirates; Yeoh SW, Australia S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Moreno-García E, Puerta-Alcalde P, Letona L, Meira F, Dueñas G, Chumbita M, Garcia-Pouton N, Monzó P, Lopera C, Serra L, Cardozo C, Hernandez-Meneses M, Rico V, Bodro M, Morata L, Fernandez-Pittol M, Grafia I, Castro P, Mensa J, Martínez JA, Sanjuan G, Marcos MA, Soriano A, Garcia-Vidal C; COVID-19-researcher group. Bacterial co-infection at hospital admission in patients with COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;118:197-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vousden N, Bunch K, Morris E, Simpson N, Gale C, O'Brien P, Quigley M, Brocklehurst P, Kurinczuk JJ, Knight M. The incidence, characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women hospitalized with symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection in the UK from March to September 2020: A national cohort study using the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS). PLoS One. 2021;16:e0251123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nasa P, Juneja D, Jain R, Nasa R. COVID-19 and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and thrombocytopenia syndrome in pregnant women - association or causation? World J Virol. 2022;11:310-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Westblade LF, Simon MS, Satlin MJ. Bacterial Coinfections in Coronavirus Disease 2019. Trends Microbiol. 2021;29:930-941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ruiz-Bastián M, Falces-Romero I, Ramos-Ramos JC, de Pablos M, García-Rodríguez J; SARS-CoV-2 Working Group. Bacterial co-infections in COVID-19 pneumonia in a tertiary care hospital: Surfing the first wave. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;101:115477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nana M, Nelson-Piercy C. COVID-19 in pregnancy. Clin Med (Lond). 2021;21:e446-e450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nasa P, Phulara R, Georgian A, Zacharia B. Inter-hospital transfer of a pregnant prone patient with COVID-19 as a bridge to ECMO. Indian J Anaesth. 2022;66:311-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zambrano LD, Ellington S, Strid P, Galang RR, Oduyebo T, Tong VT, Woodworth KR, Nahabedian JF 3rd, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Gilboa SM, Meaney-Delman D; CDC COVID-19 Response Pregnancy and Infant Linked Outcomes Team. Update: Characteristics of Symptomatic Women of Reproductive Age with Laboratory-Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Pregnancy Status - United States, January 22-October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1641-1647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 587] [Cited by in RCA: 885] [Article Influence: 177.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Oshay RR, Chen MYC, Fields BKK, Demirjian NL, Lee RS, Mosallaei D, Gholamrezanezhad A. COVID-19 in pregnancy: a systematic review of chest CT findings and associated clinical features in 427 patients. Clin Imaging. 2021;75:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Şahin D, Tanaçan A, Webster SN, Moraloğlu Tekin Ö. Pregnancy and COVID-19: prevention, vaccination, therapy, and beyond. Turk J Med Sci. 2021;51:3312-3326. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Zhao YY, Qiao J. Acute respiratory falure during pregnancy and assisted mechanical ventilation. Zhongguo Shiyong Fuke Yu Chanke Zazhi. 2021;37:139-141. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | D'Souza R, Ashraf R, Rowe H, Zipursky J, Clarfield L, Maxwell C, Arzola C, Lapinsky S, Paquette K, Murthy S, Cheng MP, Malhamé I. Pregnancy and COVID-19: pharmacologic considerations. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57:195-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Adalbert JR, Varshney K, Tobin R, Pajaro R. Clinical outcomes in patients co-infected with COVID-19 and Staphylococcus aureus: a scoping review. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen L, Liu W, Zhang Q, Xu K, Ye G, Wu W, Sun Z, Liu F, Wu K, Zhong B, Mei Y, Zhang W, Chen Y, Li Y, Shi M, Lan K, Liu Y. RNA based mNGS approach identifies a novel human coronavirus from two individual pneumonia cases in 2019 Wuhan outbreak. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:313-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 78.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ren LL, Wang YM, Wu ZQ, Xiang ZC, Guo L, Xu T, Jiang YZ, Xiong Y, Li YJ, Li XW, Li H, Fan GH, Gu XY, Xiao Y, Gao H, Xu JY, Yang F, Wang XM, Wu C, Chen L, Liu YW, Liu B, Yang J, Wang XR, Dong J, Li L, Huang CL, Zhao JP, Hu Y, Cheng ZS, Liu LL, Qian ZH, Qin C, Jin Q, Cao B, Wang JW. Identification of a novel coronavirus causing severe pneumonia in human: a descriptive study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:1015-1024. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |