Published online Aug 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i22.5373

Peer-review started: April 26, 2023

First decision: June 12, 2023

Revised: June 20, 2023

Accepted: July 17, 2023

Article in press: July 17, 2023

Published online: August 6, 2023

Processing time: 99 Days and 0.4 Hours

Traumatic amputation of the penis is a rare surgical emergency, usually caused by self-mutilation, accidents, circumcision, assault and animal attacks. This study aimed to summarize our treatment experience involving penile reconstruction in a rare case of a self-strangulation induced chronical penile partial amputation.

A 22-year-old man presented with self-strangulation induced chronical penile partial amputation for 3 mo where the penile proximal part was 1 cm far from the pubis. Reconstruction methods included end-to-end anastomosis of the urethral mucosa, proximal anastomosis of the corpus cavernosum and tunica albuginea of the penis, anastomosis of the deep dorsal vein, dorsal artery, and superficial dorsal vein. Patient urinated smoothly after the catheter was removed on day 21. 3 mo after the surgery, the patient's penile preliminary cosmetic appearance was satisfactory, with occasional morning erections. Distal penile sensation was preserved, yet erection hardness of the distal penis was not satisfactory.

Complete preoperative assessment and prompt surgical intervention decreases loss of residual penile functions.

Core Tip: We report a rare case of penile partial amputation. Through complete preoperative evaluation and appropriate surgical management, the patient's penile urination and erectile function were preserved. At the same time, the importance of psychological intervention on the rehabilitation of patients with self-injury was further discussed.

- Citation: Maimaitiming ABLT, Mulati YLSD, Apizi ART, Li XD. Self-strangulation induced penile partial amputation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(22): 5373-5381

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i22/5373.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i22.5373

Traumatic amputation of the penis is a rare surgical emergency, usually caused by self-mutilation, accidents, circumcision, assault and animal attacks[1]. Penile self-mutilation is even rarer that related to mental and mood disorders and is reported sporadically. Treatment of penile amputation requires stabilization of the patient and special attention to underlying psychiatric disorders. Therefore, for these patients, a detailed medical history should be taken to determine the patient's mental state incase for later intervention management if necessary. Studies have shown that in most cases of self-amputation, resolution and treatment of psychiatric disorders usually results in a strong desire to preserve the penis. Studies have shown that, in most cases of self-amputation, resolution and treatment of mental illness usually results in a strong desire to preserve the penis[2].

Penile amputation as a surgical emergency does not require imaging most of the time[3]. Patients often undergo surgery directly for emergencies, such as edema, swelling, cyanosis, severe pain caused by acute ischemia of the distal penis. In severe cases, the patient may even lose the penis permanently. However, the patient in our case delayed the golden time of treatment due to personal reasons. Under this situation, adequate preoperative imaging evaluation, including penis flow ultrasound, penis nerve electrophysiology and urethroscopy evaluation, will greatly help the success rate of reconstruction, the recovery of urinary and erectile function.

A 22-year-old unmarried patient complained of “repeatedly tying his penis with rubber bands for more than 3 mo” and was admitted to the andrology ward of the Urology Department of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University.

Patient’s penis was partial amputated with a residue connection about 1 cm in diameter and leaks urine at the tied shaft.

The patient stated he started to tie his penis with rubber bands discontinuously 3 mo ago. The initial binding site is about 2-3 cm proximal to the coronal groove of the penis, which lasted for about one week resulting in a defect of about 1 cm deep in the first stangulation ring so the patient released the tying rubber bands temporarily. One week later, the patient rebind the penis, which worsened her condition.

The patient denied any family history of psychiatric illness. No autism-like manifestations were found during a consultation with a psychologist.

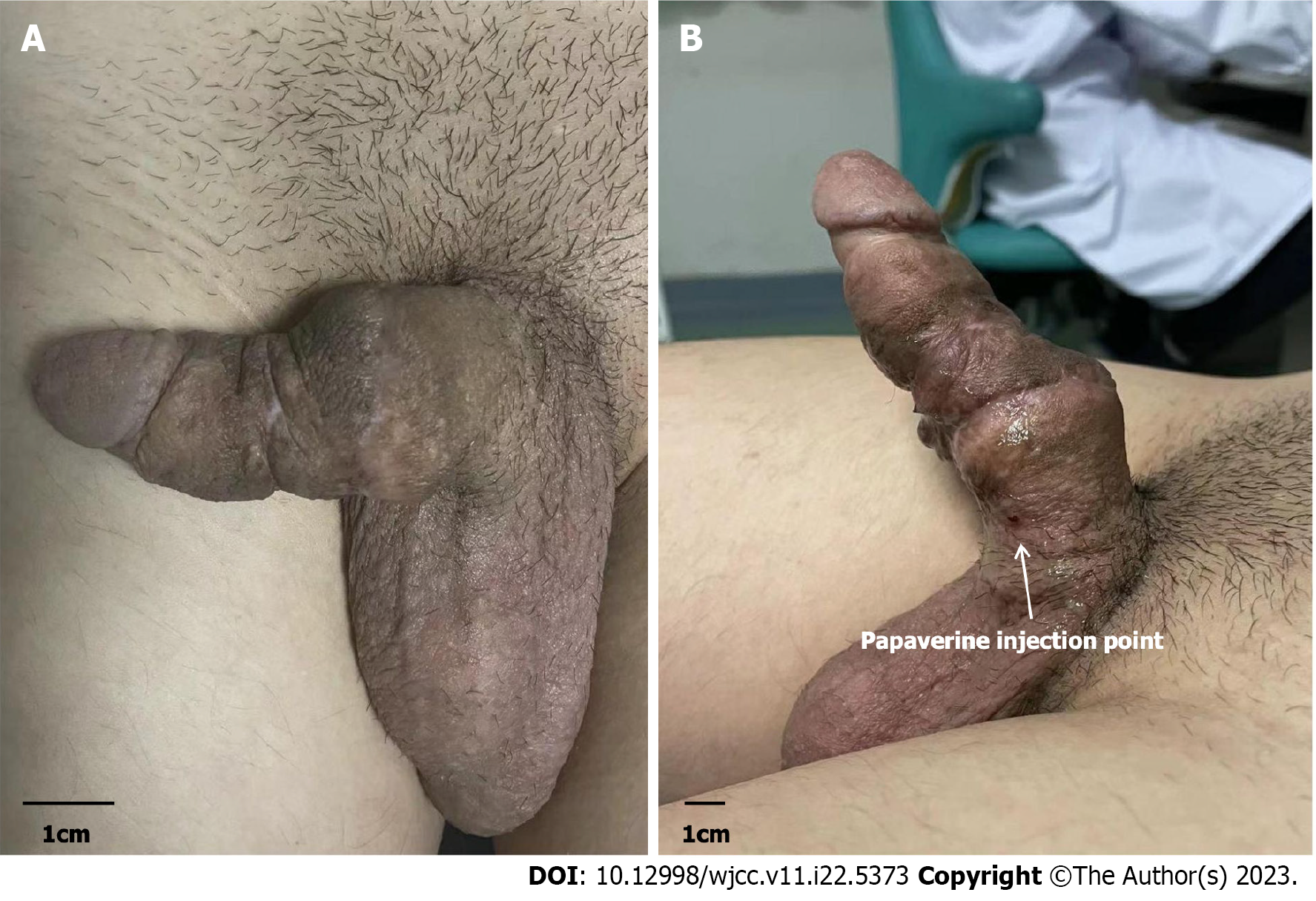

On genital examination, Partial connections remained in the proximal penis was observed (Figure 1). Postoperative follow-up showed that the penile wound was in good condition, the appearance was satisfactory, patient’s urination and erectile function were recovered (Figure 2).

The patient's laboratory test results reveal no notable abnormalities.

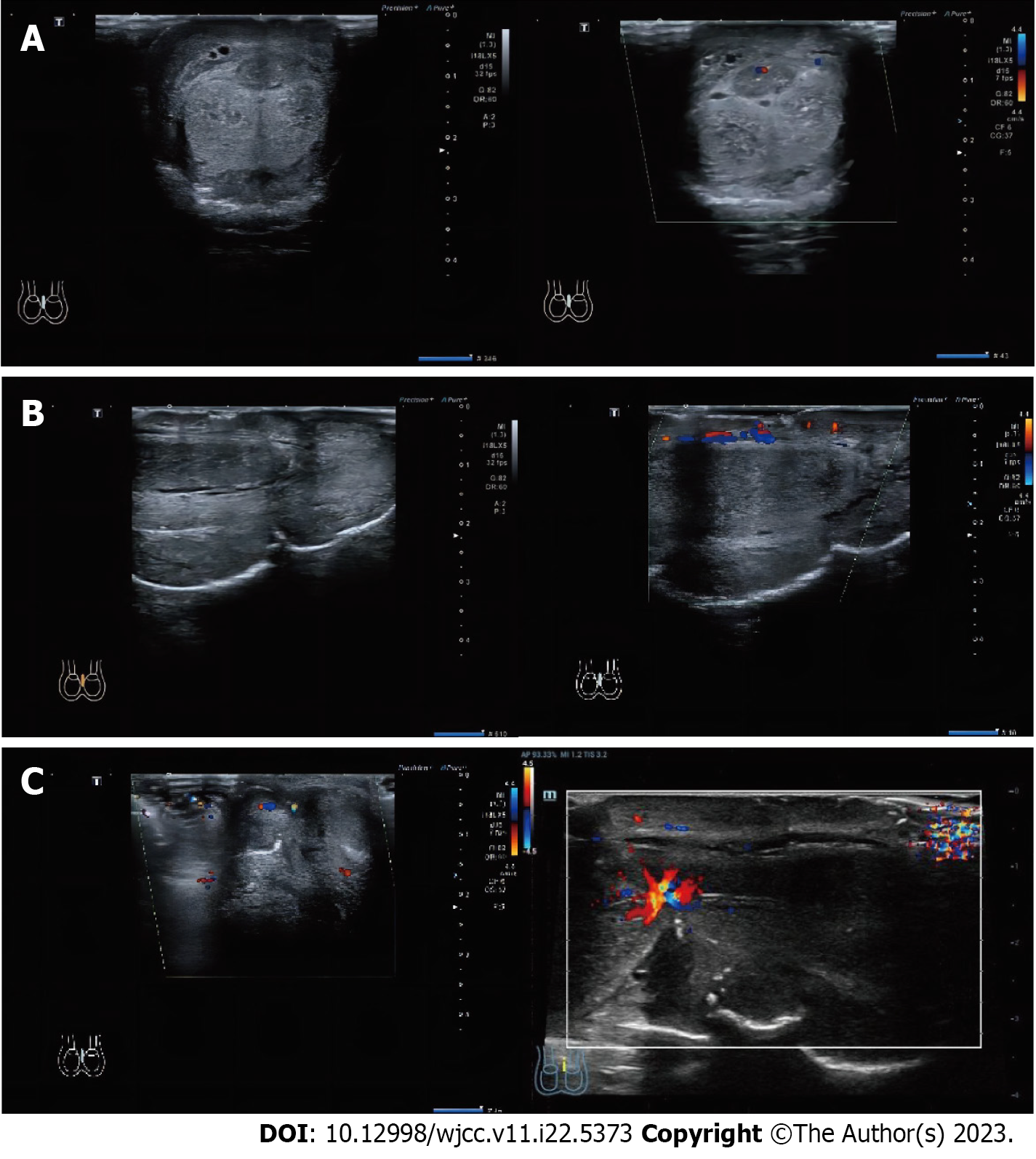

Color Doppler ultrasonography indicated that bilateral corpus cavernosum and corpus spongiosum were severed near the root of the penis; there is blood flow distribution in part of the cortex of the severed penis; part of the penile fascia at the part of the severed penile fascia is still continuous, and blood flow is seen in the continuous fascia, but no obvious blood flow signal was found in the severed corpus cavernosum and corpus spongiosum (Figure 3).

Flexible cystoscopy (Video 1): Using a flexible cystoscope to enter the urethra, a circular stenosis can be seen in the urethra about 8 cm away from the external urethral orifice where the flexible cystoscope cannot pass through. Meanwhile, the flexible cystoscope guide light can be seen outside the second strangulation ring.

The patient was finally diagnosed with strangulation induced penile partial amputation.

Considering that the patient's distal penile blood supply was still residual, replantation might maintain good blood perfusion, we decided to perform penile reimplantation surgery with the core goal of maximizing the preservation of the patient's long-term urination and erectile function for the patient. The surgery was performed under general anesthesia by two urologists who were skilled in penile reconstruction surgery.

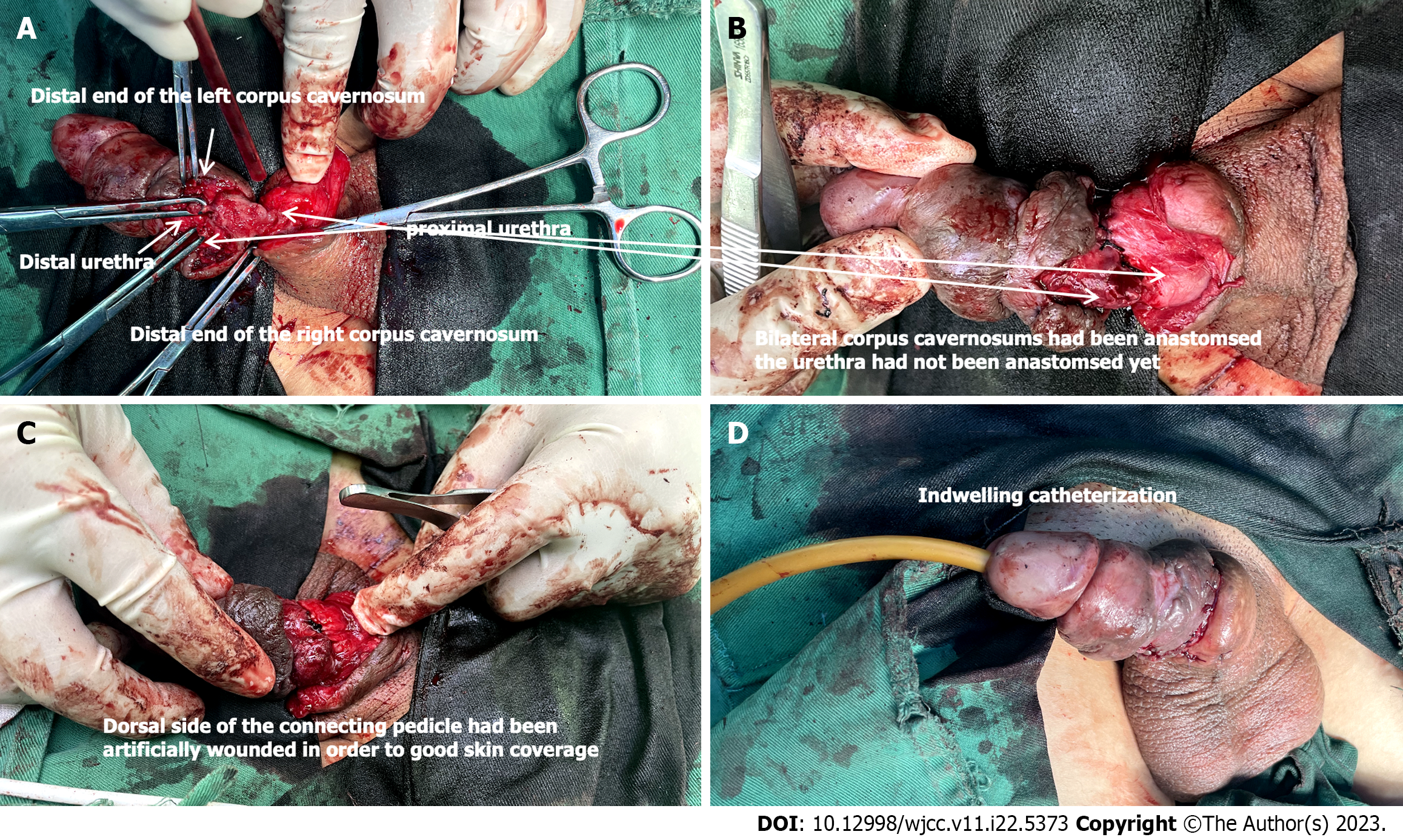

Preoperative observations: The penis was seen to be semi-disconnected at the root, the penile corpus cavernosum and urethral sponge were disconnected, the disconnected stump had skin attached, and the urethra was narrowed at both ends of the dissection. The residual connecting tissues were hard in texture and the thinnest diameter was about 7 mm, and ultrasound confirmed that there was a small amount of arterial blood flow signal inside the area. The arterial flow signal decreased after twisting the penis. A slight strangulation of the penile body was seen 2 cm from the external urethra, the distal penile skin temperature was low, and the original skin recovered red slowly after pressing the glans, which was considered to be in an ischemic state.

Surgical procedure: Adequate preoperative disinfection of the surgical area was performed. Circumferentially incised the skin attached to the stump, freed the proximal urethra, excised the narrowed part of the urethra to fully expose the normal urethra. Same approach were used for the proximal dissection of the urethra and penile corpus cavernosum. Trabeculated epidermis at the site of the connecting tissue could be buried under the skin. Due to the dorsal neuro

The catheter was maintained for 21 d after surgery. Postoperative follow-ups are shown in Figure 3. Three months after reconstruction, the preliminary cosmetic appearance was satisfactory with occasional morning erection. Patient had a grade 3 erection according to The Erection Hardness Score after injected papaverine into the corpus cavernosum during the penile ultrasound examination (Figure 5). Pharmarco penile duplex color doppler ultrasonograghy assessment data 3 mo after surgery was shown in Table 1. The patient was satisfied with the restoration of reconstruction.

| Before injection | 5 min after | 10 min after | ||

| Corpus cavernosum (mm) | ||||

| L | 1.1 | 2 | 2 | |

| R | 1.1 | 1.9 | 1.9 | |

| Deep dorsal penile artery (mm) | ||||

| L | 0.4 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| R | 0.4 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| PSV (cm/s) | ||||

| L | / | 65 | 89.9 | |

| R | / | 56.3 | 64.8 | |

| EDV (cm/s) | ||||

| L | / | -3.9 | -6.7 | |

| R | / | -4.3 | -4.9 | |

| RI | ||||

| L | / | -1.1 | -1.1 | |

| R | / | -1.1 | -1.1 |

Penile amputation is a rare and challenging injury, like other traumatic penile injuries including penile fracture, penetrating penile injuries and penile soft tissue injuries, it is considered as emergency[4]. But cases of chronic strangulated partial penile amputation have not been reported so far. This case report may be the first to be reported. To this end, we reviewed relevant literature to summarize key points and experiences in the treatment of acute penile trauma.

The most common complications after amputation penile reconstruction include skin necrosis, penile skin hypoesthesia, urethral stricture, erectile dysfunction, and urethral fistula[1]. Previous studies determined that immediate penile exploration and blood supply recovery are considered the most common and current management of penile amputation with experts demonstrating that it leads to the fastest recovery in erectile, urinary function and positive cosmetic outcomes[5]. Based on the summary of relevant literature and case reports, we conclude that amputation type, tissue defect area, ischemic time and urethral injury are factors that need to be evaluated before surgery. These have a significant impact on the success of penile replantation or reconstruction. It should be emphasized that a thorough physical examination should not delay surgical intervention, as better intraoperative examination can be achieved in the operating room.

Types of penile amputation include total and partial amputations. Although there are still tissue connections in partial penile amputation, the degree of tissue damage in partial penile amputation is sometimes more severe than that in total amputation. Morrison et al[6] concluded in their study that critically appraises the current literature on penile replantation that complete amputation seems to predict better sensory outcomes in bivariate analysis. Complete penile amputation may give the surgeon better access to nerves for neurorrhaphy, which ultimately could allow for better sensation. In particular, the asymmetry of the dissected tissue caused by strangulation will lead to poor postoperative anastomosis and affect the surgical effect. As for total penile amputation caused by neat cutting, the wound conditions will be easier to manage but also total amputation usually means more severe ischemia.

Facing cases with large tissue defects, in order to achieve the maximum restorative effect, local plastic correction is needed, which generally needs to be decided according to the patient's condition. Available choices include abdominal wall under the island flap, groin flap and other conditional flaps with less subcutaneous fat and no obvious variation in vascular distribution. Scrotal flaps are also used in a few cases. However, due to the large number of folds and pores of scrotal flaps, the filled defects often have poor appearance after repair and obvious scar remains.

The application of microsurgery downstream free flap transplantation makes the reconstruction and repair of penile injuries with large tissue defects more diversified. At present, various free skin flaps, such as radial free forearm flap, superficial inferior epigastric artery flap and superficial circumflex iliac artery flap, had been attempted for phallic construction, aiming at functional as well as cosmetic result[7].

According to reports in the literature, the survival rate was higher after replantation if the duration of warm ischemia was < 6 h, or the duration of cold ischemia was < 16 h for the amputated organs[8]. Previous studies suggested that total ischemic time of the penis below 15 h (mean 7 h) is associated with the successful outcome of the penile replantation. Henry et al[9] reported a successful case of penile reconstruction after 23 h of ischemia[9]. Although there is no unified standard for the golden time limit of ischemic time after penile amputation, the shorter the amputation time, the higher the success rate of replantation and reconstruction.

A consensus in the contemporary literature acknowledges that the microsurgical revascularization and approximation of the penile shaft structures provide early and adequate restoration of penile blood flow with the best outcome of penile replantation survival, erectile and voiding functions[10-12]. For cases with urethral injury, adequate intraoperative evaluation was performed to clarify the type of urethral penile injury, including partial and complete rupture. According to the treatment principle of anterior urethral injury, simple indwelling catheter and urethral repair were used respectively.

Retrograde urethrocystography (RGU) can detect contrast agent leakage at the site of occult urethral rupture. Some authors consider RGU to be compulsory if diagnosis of urethral rupture is suspected[13,14]. At the same time, RGU can also evaluate and diagnose the postoperative complications such as urethral fistula and urethral stricture.

Principles of penile reconstruction surgery are: Judiciously debride necrotic tissue, anastomose the severed urethra, repair the tunica albuginea and microsurgical repair for the dorsal nerves, arteries and veins[2,15-17]. Ottaiano et al[18] summarized in a review of the literature on reconstruction that immediate reconstruction of penile injuries typically occurs by means of suspension or entrapment can reduce complications[18]. Recent publications have investigated the anatomical approaches to penile allografts and suggested that connection of cavernosal, dorsal, and pudendal arteries would allow for optimal reperfusion[10,19].

Previous studies have also suggested that microvascular repair yields superior outcomes, especially for venous out-flow[20,21]. Babaei et al[22] summarized that although the initial reconstruction under direct vision had a good effect on the recovery of appearance and urination function in most cases, skin necrosis and other complications were also common. With the application of microscopic technology, reconstruction meeting higher and higher anatomical requirements, especially the microsurgical anastomosis of penile blood vessels and nerves, which reduces the risk of penile skin necrosis.

Besides corporeal sinusoidal blood flow and its venous outflow are two critical factors for successful survival of penile replantation. Some authors contend that the arteries do not provide a significant amount of vascular flow, add more operative time, and result in damage to the erectile tissue. However, studies showed that erectile function remains in up to 86%, penile sensation up to 82% of patients who undergo microvascular reanastomosis of the dorsal arteries, although this may be diminished when compared with preinjury state[23]. In Zhong et al’s study, they also mentioned using hyperbaric oxygen to accelerate the healing process which was of particular interest[23]. Damage assessing of the arteries and veins along with microvascular reanastomosis are very helpful for the surgical outcomes and reducing complications. Multiple venous anastomoses help to reduce venous congestion. Superficial veins help to ensure skin vitality as well as the dorsal deep veins[24]. Morrison et al[6] reviewed 74 published articles related to this topic, and reported the outcomes and replantation-related complications in 106 cases. Complete penile amputation accounted for 74.8% of these men, most of whom recovered micturition (97.4%) and erectile functions (77.5%). Skin necrosis (54.8%) and venous thrombosis (20.2%) were the most common complications. Multivariate analysis indicated anastomosis of a great number of the dorsal arteries and nerves were associated with better sexual function and recovery of urination along with normal sensation. Moreover, the number of anastomosed vessels was negatively correlated with adverse outcomes. During the perioperative period, routine observations include penile skin color, filling, overall vitality, temperature, and capillary refilling time[9]. Arterial blood flow should be monitored using a hand-held Doppler device, and the observation time can be arranged according to the actual situation.

Whether it is penile amputation caused by accidental injury or self-harm behavior, it is very important to evaluate the patient's psychological and mental health during the whole treatment cycle, as well as the necessary psychological intervention. Especially for patients presenting with self-harm behavior.

Currently, relevant surgical literatures have not paid special attention to the mental health of such patients. However, it is very common for patients with penile amputation to experience a series of stress reactions after the injury. According to the severity of the patient's condition, personality characteristics, education level and other aspects, the clinical manifestations of this stress response are mild or severe, and psychological changes are common phenomena. In addition to negative emotions such as sadness and depression, increased psychological vigilance, avoidance, hyperactivity, anxiety, and impaired self-cognition may affect the treatment effect. In particular, the postoperative body image disorder makes the patient have an unacceptable aversion to the reconstructed and repaired penis, and extreme patients may self-harm again[25]. Therefore, helping patients to establish a positive concept of coping with stress and conducting corresponding psychological counseling in a timely manner are indispensable for patients who have undergone penile reconstruction surgery in receiving the reconstructed penis and physical and mental health recovery after surgery.

Penile amputation is a rare emergency in urology. It is necessary to evaluate the damage of the penis, and immediate surgical treatment is essential for the recovery of appearance, urination, and erectile function of the truncated penis[26-28]. Reconstruction should be performed to the greatest extent possible, although very few patients may face delays in the optimal timing of treatment. At the same time, psychological concern and treatment guidance for patients with penile amputation are also a link that needs to be paid attention to in clinical practice.

We thank the patient and all participating authors for their contributions.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Othmen MB, Tunisia; Sarier M, Turkey; Surani S, United States S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang XD

| 1. | Raheem OA, Mirheydar HS, Patel ND, Patel SH, Suliman A, Buckley JC. Surgical management of traumatic penile amputation: a case report and review of the world literature. Sex Med. 2015;3:49-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chou EK, Tai YT, Wu CI, Lin MS, Chen HH, Chang SC. Penile replantation, complication management, and technique refinement. Microsurgery. 2008;28:153-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bachoo S, Batura D. Fractures of the penis. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2021;82:1-9. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Patial T, Sharma G, Raina P. Traumatic penile amputation: a case report. BMC Urol. 2017;17:93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kominsky H, Beebe S, Shah N, Jenkins LC. Surgical reconstruction for penile fracture: a systematic review. Int J Impot Res. 2020;32:75-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Morrison SD, Shakir A, Vyas KS, Remington AC, Mogni B, Wilson SC, Grant DW, Cho DY, Rahnemai-Azar AA, Lee GK, Friedrich JB, Mardini S. Penile Replantation: A Retrospective Analysis of Outcomes and Complications. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2017;33:227-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Salem HK, Mostafa T. Primary anastomosis of the traumatically amputated penis. Andrologia. 2009;41:264-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lowe MA, Chapman W, Berger RE. Repair of a traumatically amputated penis with return of erectile function. J Urol. 1991;145:1267-1270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Henry N, Bergman H, Foong D, Filobbos G. Successful penile replantation after complete amputation and 23 h ischaemia time: the first in reported literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Biswas G. Technical considerations and outcomes in penile replantation. Semin Plast Surg. 2013;27:205-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jezior JR, Brady JD, Schlossberg SM. Management of penile amputation injuries. World J Surg. 2001;25:1602-1609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Roche NA, Vermeulen BT, Blondeel PN, Stillaert FB. Technical recommendations for penile replantation based on lessons learned from penile reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2012;28:247-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mydlo JH, Hayyeri M, Macchia RJ. Urethrography and cavernosography imaging in a small series of penile fractures: a comparison with surgical findings. Urology. 1998;51:616-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ganem JP, Kennelly MJ. Ruptured Mondor's disease of the penis mimicking penile fracture. J Urol. 1998;159:1302. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Amer T, Wilson R, Chlosta P, AlBuheissi S, Qazi H, Fraser M, Aboumarzouk OM. Penile Fracture: A Meta-Analysis. Urol Int. 2016;96:315-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Morey AF, Metro MJ, Carney KJ, Miller KS, McAninch JW. Consensus on genitourinary trauma: external genitalia. BJU Int. 2004;94:507-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shaeer O. Restoration of the penis following amputation at circumcision: Shaeer's A-Y plasty. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1013-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ottaiano N, Pincus J, Tannenbaum J, Dawood O, Raheem O. Penile reconstruction: An up-to-date review of the literature. Arab J Urol. 2021;19:353-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tuffaha SH, Sacks JM, Shores JT, Brandacher G, Lee WPA, Cooney DS, Redett RJ. Using the dorsal, cavernosal, and external pudendal arteries for penile transplantation: technical considerations and perfusion territories. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:111e-119e. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Darewicz B, Galek L, Darewicz J, Kudelski J, Malczyk E. Successful microsurgical replantation of an amputated penis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2001;33:385-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Babaei AR, Safarinejad MR. Penile replantation, science or myth? A systematic review. Urol J. 2007;4:62-65. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Babaei A, Safarinejad MR, Farrokhi F, Iran-Pour E. Penile reconstruction: evaluation of the most accepted techniques. Urol J. 2010;7:71-78. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Zhong Z, Dong Z, Lu Q, Li Y, Lv C, Zhu X, Zhao X, Zhang X, Morales F, Ichim TE. Successful penile replantation with adjuvant hyperbaric oxygen treatment. Urology. 2007;69:983.e3-983.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yang M, Zhao M, Li S, Li Y. Penile reconstruction by the free scapular flap and malleable penis prosthesis. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59:95-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gui YT, Cai ZM, Zhu H. Penile Reconstruction. Beijing: Peking University Medical Press, 2010. |

| 26. | Noh J, Kang TW, Heo T, Kwon DD, Park K, Ryu SB. Penile strangulation treated with the modified string method. Urology. 2004;64:591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cook A, Khoury AE, Bagli DJ, Farhat WA, Pippi Salle JL. Use of buccal mucosa to simulate the coronal sulcus after traumatic penile amputation. Urology. 2005;66:1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Charlesworth P, Campbell A, Kamaledeen S, Joshi A. Surgical repair of traumatic amputation of the glans. Urology. 2011;77:1472-1473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |