Published online Aug 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i22.5338

Peer-review started: March 30, 2023

First decision: April 26, 2023

Revised: May 16, 2023

Accepted: June 26, 2023

Article in press: June 26, 2023

Published online: August 6, 2023

Processing time: 125 Days and 21.7 Hours

Acquired haemophilia (AH) is a serious autoimmune haematological disease caused by the production of auto-antibodies against coagulation factor VIII. In some patients, AH is associated with a concomitant malignancy. In case of surgical intervention, AH poses a high risk of life-threatening bleeding.

A 60-year-old female patient with multiple recurrences of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer underwent transurethral tumour resection. A severe haematuria developed postoperatively warranting two endoscopic revisions; however, no clear source of bleeding was identified in the bladder. Subsequent haematological examination established a diagnosis of AH. Treatment with factor VIII inhibitor bypass activity and immunosuppressive therapy was initiated immediately. The patient responded well to the therapy and was discharged from the hospital 21 d after the primary surgery. At the 38-mo follow-up, both AH and bladder cancer remained in complete remission.

AH is a rare, life-threatening haematological disease. AH should be considered in patients with persistent severe haematuria or other bleeding symptoms, especially if combined with isolated activated partial thromboplastin time prolongation.

Core Tip: Patients with acquired haemophilia A, even those who have never experienced any previous haemorrhagic event, are at high risk of severe life-threatening bleeding in case that they need surgery. It is a rare disease that is often overlooked in the differential diagnosis, resulting in a delay with the risk of life-threatening consequences. Therefore, it is essential to avoid underestimating of the isolated prolongation of the activated partial thromboplastin time or other altered coagulation parameters detected prior to surgery.

- Citation: Ryšánková K, Gumulec J, Grepl M, Krhut J. Acquired haemophilia as a complicating factor in treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(22): 5338-5343

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i22/5338.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i22.5338

Haemophilia is a gonosomal, recessively inherited bleeding disorder. Haemophilia A is caused by a mutation in the gene that encodes coagulation factor VIII, while haemophilia B is caused by a mutation in the gene that encodes coagulation factor IX. The prevalence of haemophilia A is 1/5000 and that of haemophilia B is 1/30000[1]. Haemophilia is diagnosed based on typical clinical symptoms, laboratory evaluation, and genetic tests. In most cases, it is treated by coagulation factor substitution.

Acquired haemophilia (AH) is much less understood. This serious haematological disease is caused by the production of auto-antibodies against coagulation factor VIII. The estimated incidence is 0.2-1.5/1000000, but many cases remain undiagnosed[2,3]. The pathogenesis of AH is unknown. In some patients, AH is associated with a concomitant malignancy or autoimmune disease. The association of AH with bladder cancer is rare[2]. Here, we describe a previously undiagnosed patient with AH, in whom an uncomplicated transurethral resection of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer led to severe haematuria.

A 60-year-old woman developed severe haematuria after elective endoscopic surgery - transurethral resection of multiple recurrent bladder tumours.

In August 2019, a small recurrence developed, and the patient was referred for another transurethral resection of the bladder tumour (TURBT). At the time of hospital admission, the patient had a normal prothrombin time; however, her activated partial thromboplastin time (APPT) was prolonged. This abnormal laboratory finding was initially missed. Immediately after the TURBT, severe haematuria developed. The precipitous drop of haemoglobin to a value of 70 g/L and haemorrhagic shock required intensive care including blood transfusions and coagulation factor substitution. In order to identify the source of bleeding, two consecutive endoscopic revisions were performed within the next 7 d. No clear source of haematuria was identified.

In July 2018, a bladder tumour was diagnosed during an ultrasound examination, and a TURBT was performed. Histology had revealed a non-invasive low-grade urothelial carcinoma. A single dose of intravesical therapy with mitomycin C was administered. At that time, all coagulation parameters were normal, and no postoperative complications developed. In March 2019, multiple superficial recurrences were identified, warranting another TURBT. A histological examination confirmed a non-invasive, low-grade urothelial carcinoma. There were no complications during or after this surgery as well.

The patient had a history of hypertension and osteoporosis, but no other severe comorbidities. She did not report any previous symptoms of coagulopathy. Her family history regarding bleeding disorders was negative.

The patient’s physical examination revealed only haematuria, without other bleeding symptoms.

Changes in the coagulation factors over time are shown in Table 1.

| Parameter (physiological range) | Hospital admission (October 2019) | Acquired haemophilia diagnosed (December 11, 2019) | Treatment start (cyclophosphamide + prednisone) | Clinical and laboratory remission (December 2019) | Laboratory relapse (rituximab, February 2020) | Last TURBT (June 2020) |

| APTT-R (0.8-1.2) | 1.71 | 2.42 | 2.38 | 0.98 | 1.2 | 0.81 |

| FVIII (50%-150%) | - | 2% | 0.8% | 81.6% | 32% | 206% |

| Inhibitor FVIII (0.0-0.8 BU/L) | - | - | 33 BU/L | 0.8 BU/L | 1.0 BU/L | 0.3 BU/L |

| Haemoglobin (120-160 g/L) | 118 g/L | 87 g/L | 86 g/L | 113 g/L | 113 g/L | 138 g/L |

| Platelets (150-400) × 109/L | 293 × 109/L | 291 × 109/L | 403 × 109/L | 366 × 109/L | 340 × 109/L | 318 × 109/L |

| INR | 1.0 | 1.04 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| Bleeding symptoms | - | Haematuria | Haematuria | - | - | - |

Ultrasound examination of the upper urinary tract did not reveal any major pathology.

Seven days after the primary surgery, due to persistent haematuria, a haematological examination was performed. At this time point, the haematologist included AH in the differential diagnosis for the first time. Subsequently, at day 10 after the primary TURBT, a final diagnosis of AH was made. Changes in the coagulation factors over time are shown in Table 1.

Before the final diagnosis was made, two consecutive endoscopic revisions were performed, and the patient received eight units of plasma, four units of erythrocytes without buffy coat, and activated recombinant factor VII (NovoSeven, Novo Nordisk A/S, Denmark) with no effect on bleeding. After confirmation of AH, treatment with factor VIII inhibitor bypass activity and immunosuppressive therapy (prednisone with cyclophosphamide) was immediately initiated, according to current guidelines[4]. In a course of 6 d, the bleeding subsided and haematuria gradually stopped. On day 10 after treatment initiation, normal activity of the factor VIII was confirmed and the level of factor VIII antibodies decreased.

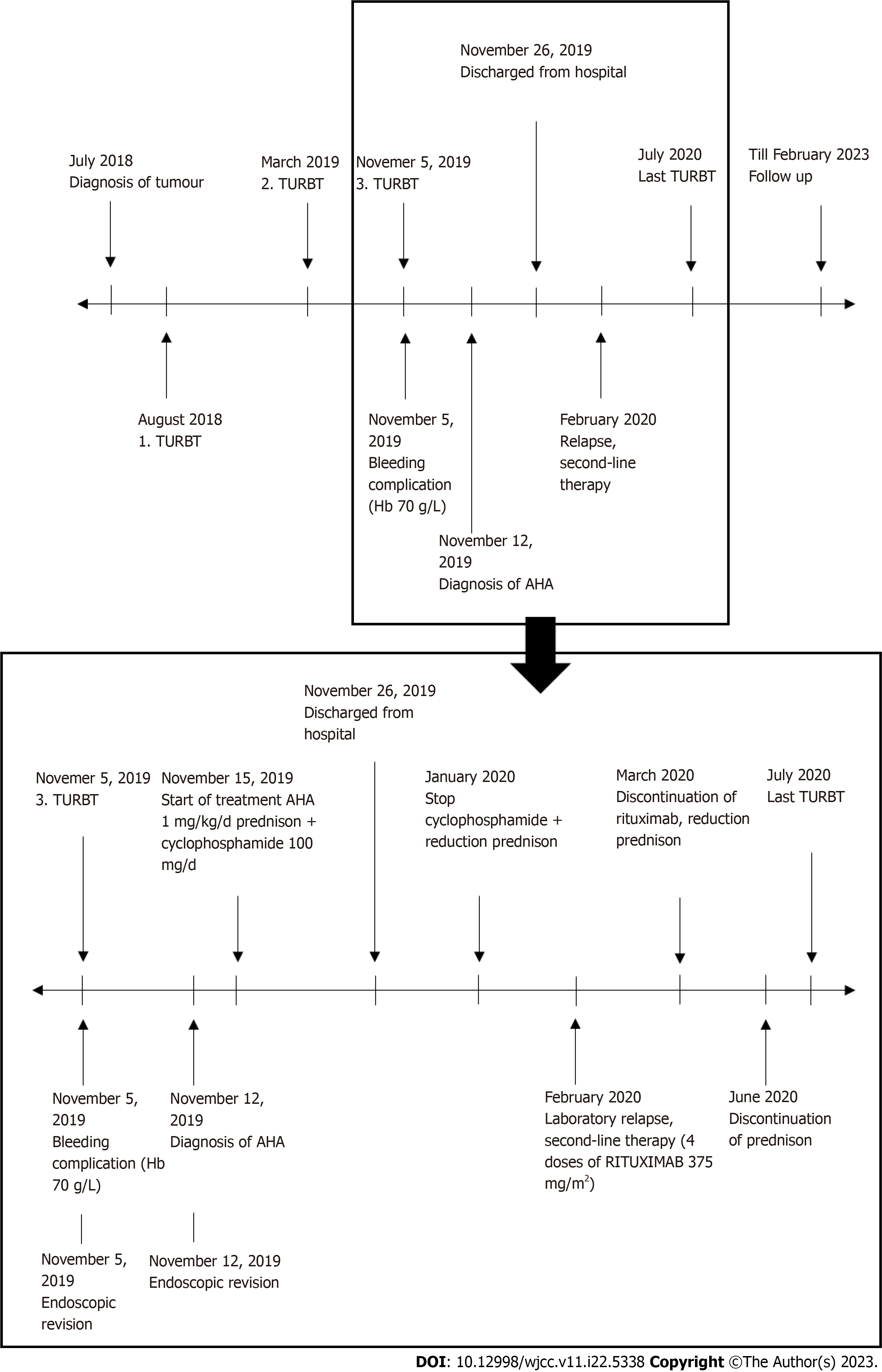

On day 21 after the primary TURBT, the patient was discharged from the hospital. The immunosuppressive therapy dose was gradually reduced, but in February 2020, a relapse of AH was detected based on laboratory results, without bleeding symptoms. Thus, a second line of immunosuppressive treatment was started, with a monoclonal antibody against the CD20 antigen (rituximab). Gradually, the laboratory parameters normalized, and disease remission was achieved. In June 2020, another recurrence of bladder cancer was detected. No specific preventive haematologic measures were adopted prior to surgery, as coagulation parameters were normal at that time. The TURBT and the postoperative course were without complications. Subsequently, the patient received a one-year course of intravesical chemotherapy, as recommended by the European Association of Urology guidelines[5]. As of February 2023, both AH and bladder cancer are in complete remission. The patient attends regular urology and haematology follow-ups. Figure 1 offers the course of disease and therapy of AH.

AH is a rare, potentially life-threatening autoimmune disease. In general, the incidence of AH is similar in both sexes. It is higher in women between 20 and 40 years of age, as AH may develop after childbirth[6]. Additionally, the incidence is known to increase in both men and women over 60 years of age.

AH frequently manifests as a subcutaneous haematoma or bleeding into the muscles, gastrointestinal or urogenital tract, epistaxis, or intracranial bleeding. Bleeding into the joints, typical for congenital haemophilia, occurs infrequently in AH[7,8]. Up to 10% of patients with AH remain asymptomatic. AH-related mortality is estimated to be 3%[9]. Even after successful treatment, 12%-18% of patients are at risk of relapse; therefore, all patients require long-term monitoring[4].

The aetiology of AH is unknown. About half the cases are idiopathic, and the other half are associated with various conditions, including malignant tumours (most frequently lung or prostate cancer), autoimmune diseases, drug abuse, or allergy. AH in patients with bladder cancer is extremely rare, with only three cases reported to date[10]. Unlike in our case report, a number of risk factors for AH development were reported in all previously reported cases. These included sepsis or lupus anticoagulant. In our case the only potential risk factor for AH development was bladder cancer[2,3,11] (Table 2). In this case the only symptom was severe post-TURBT haematuria. In contrast, in all three previously reported cases other bleeding symptoms were present, including subcutaneous and intramuscular hematomas, which led to earlier inclusion of coagulopathy in the differential diagnosis.

| Parameter (physiological range) | Case 1[3] | Case 2[2] | Case 3[11] | Presented case |

| Bladder cancer. Sepsis. Rectal cancer | Bladder cancer. Sepsis | Bladder cancer. Lung mass. Lupus anticoagulant | Bladder cancer | |

| FVIII (50%-150%) | ≤ 1% | 1% | 2% | |

| Inhibitor FVIII (0.0-0.8 BU/L) | 64 BU/L | 57 BU/L | 250 BU/L | 33 BU/L |

| Bleeding symptoms | Hematothorax. Subcutaneous haematoma | Intramuscular haematoma. Subcutaneous haematoma | Intramuscular haematoma. Subcutaneous haematoma | Haematuria |

| Therapy | Cyclophosphamide and prednisone | Cyclophosphamide and prednisone. Rituximab | Cyclophosphamide and prednisone. Rituximab | Cyclophosphamide and prednisone. Rituximab |

The AH diagnosis is based on laboratory tests. It is associated with isolated APTT prolongation and antibodies against factor VIII, which reduce its coagulation activity. Both the prothrombin time and the number of platelets are normal. The mixing plasma test is the initial diagnostic tool, but the Bethesda test is considered confirmatory in making the final diagnosis[4]. Neither the level of antifactor VIII antibodies nor factor VIII activity is directly proportional to bleeding severity, but both may predict disease progression, the treatment response, and overall survival rate[9].

Kreuter et al[3] suggested that patients with malignancies that fail AH therapy often have advanced or metastatic disease. They also reported that in 20% of patients, curing malignancy led to the disappearance of anti-factor VIII antibodies. The prompt response to immunosuppressive treatment of AH in our patient could be related to her younger age and favourable stage of the disease[12,13].

Since AH is considered a sporadic disease, the European Acquired Haemophilia registry was founded[14] to promote the development of internationally accepted diagnostic and treatment guidelines. Treatment of AH consists of haemostatic and immunosuppressive therapy. The treatment in patients with mild form of AH starts with corticosteroids. In cases where the levels of anti-factor VIII antibodies are high, combination with cyclophosphamide or rituximab is recommended. Adverse events of immunosuppressive therapy occur in more than 50% of patients[4]. They may include cardiovascular events such as stroke or myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, neutropenia, sepsis, and psychiatric disorders[7]. In addition, the rebound elevation of factor VIII may lead to thromboembolic events.

In clinical practice, early diagnosis is important for successful treatment. However, an appropriate diagnosis and subsequent treatment are often delayed, because patients with AH-related bleeding are mostly encountered by physicians without expertise in haematology. In the present case study, the patient was admitted to the hospital with laboratory signs of AH, and despite APTT values in the pathological range and severe bleeding, the diagnosis was delayed by 10 d. It is therefore important that the urologists and other surgical specialists include this disease in their differential diagnosis when encountering prolonged bleeding. Patients with AH, even those who have never experienced any previous haemorrhagic event, are still at high risk of severe life-threatening bleeding associated with surgery. Therefore, it is essential to avoid underestimation of the isolated prolongation of the APPT or abnormalities in any other coagulation parameters detected prior to surgery[4].

AH is a rare, potentially life-threatening haematological disease. It is important to consider AH in the differential diagnosis of patients with haematuria or other bleeding symptoms, when combined with isolated APTT prolongation.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author’s Membership in Professional Societies: European Association of Urology, EAU-113068.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Czech Republic

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Crocetto F, Italy; Imai Y, Japan S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Castaman G, Matino D. Hemophilia A and B: molecular and clinical similarities and differences. Haematologica. 2019;104:1702-1709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Taza F, Suleman N, Paz R, Haas C. Acquired Hemophilia A and urothelial carcinoma. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2021;11:89-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kreuter M, Retzlaff S, Enser-Weis U, Berdel WE, Mesters RM. Acquired haemophilia in a patient with gram-negative urosepsis and bladder cancer. Haemophilia. 2005;11:181-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tiede A, Collins P, Knoebl P, Teitel J, Kessler C, Shima M, Di Minno G, d'Oiron R, Salaj P, Jiménez-Yuste V, Huth-Kühne A, Giangrande P. International recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of acquired hemophilia A. Haematologica. 2020;105:1791-1801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 43.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | EAU Guidelines. Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer (TaT1 and CIS). [cited 10 January 2023]. Available from: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer. |

| 6. | Collins PW. Treatment of acquired hemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:893-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Janbain M, Leissinger CA, Kruse-Jarres R. Acquired hemophilia A: emerging treatment options. J Blood Med. 2015;6:143-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pai M. Acquired Hemophilia A. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2021;35:1131-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Knöbl P. Prevention and Management of Bleeding Episodes in Patients with Acquired Hemophilia A. Drugs. 2018;78:1861-1872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Napolitano M, Siragusa S, Mancuso S, Kessler CM. Acquired haemophilia in cancer: A systematic and critical literature review. Haemophilia. 2018;24:43-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Onitilo AA, Skorupa A, Lal A, Ronish E, Mercier RJ, Islam R, Lazarchick J. Rituximab in the treatment of acquired factor VIII inhibitors. Thromb Haemost. 2006;96:84-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ferro M, Chiujdea S, Musi G, Lucarelli G, Del Giudice F, Hurle R, Damiano R, Cantiello F, Mari A, Minervini A, Busetto GM, Carrieri G, Crocetto F, Barone B, Caputo VF, Cormio L, Ditonno P, Sciarra A, Terracciano D, Cioffi A, Luzzago S, Piccinelli M, Mistretta FA, Vartolomei MD, de Cobelli O. Impact of Age on Outcomes of Patients With Pure Carcinoma In Situ of the Bladder: Multi-Institutional Cohort Analysis. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2022;20:e166-e172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Herr HW. Age and outcome of superficial bladder cancer treated with bacille Calmette-Guérin therapy. Urology. 2007;70:65-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Knoebl P, Marco P, Baudo F, Collins P, Huth-Kühne A, Nemes L, Pellegrini F, Tengborn L, Lévesque H; EACH2 Registry Contributors. Demographic and clinical data in acquired hemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia Registry (EACH2). J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:622-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 313] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |