Published online Aug 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i22.5288

Peer-review started: April 4, 2023

First decision: May 11, 2023

Revised: June 7, 2023

Accepted: June 30, 2023

Article in press: June 30, 2023

Published online: August 6, 2023

Processing time: 120 Days and 20.7 Hours

Acute liver injury (ALI) refers to inflammation of the hepatic parenchyma without hepatic encephalopathy that lasts less than 6 mo. When the etiology is unknown, Acute Hepatitis of Unknown Origin (AHUO) can present as a diagnostic and treatment challenge. AHUO in the adult population is unusual and poorly documented. It has an incidence between 11% and 75%. Currently, no treatment guidelines exist. With no identified cause, treatment is often blind, and the wrong treatment plan may have unintended consequences.

We present the case of a 58-year-old woman who presented to the emergency room for elevated liver function tests (LFTs). Her symptoms started 10 d prior to admission and included nausea, vomiting, jaundice, decreased appetite, weight loss of 10 lbs, and dark urine. She denied drinking alcohol or taking any hepa

Idiopathic hepatitis makes treatment challenging. It can leave patients feeling confused and unfulfilled. Thus, educating the patient thoroughly for shared decision-making and management becomes essential.

Core Tip: Despite a thorough work-up (history, physical, labs, etc.), the etiology of acute hepatitis may remain a mystery. While common in children, this medically challenging situation is rare and understudied in adults. A review of the current literature reveals that the incidence is between 11% and 75%, yet no clear treatment guideline exists. Below we report the case of a 58-year-old woman with symptomatic acute hepatitis with unknown etiology, and we describe the treatment plan and rationale. In general, steroids could be considered as a possible treatment for acute hepatitis of unknown etiology. However, it was ultimately not used in our patient because of the potential risk of adverse side effects from steroid use, and an infectious etiology could not be definitively ruled out. In this situation, patient education was essential for shared decision making.

- Citation: Dass L, Pacia AMM, Hamidi M. Acute hepatitis of unknown etiology in an adult female: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(22): 5288-5295

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i22/5288.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i22.5288

Acute liver injury (ALI) or acute hepatitis refers to inflammation of the hepatic parenchyma that lasts less than 6 mo. As opposed to acute liver failure, no hepatic encephalopathy is present, but patients may still be coagulopathic (International Normalized Ratio (INR) > 1.5)[1]. In general, the presentation of acute hepatitis includes a variation of the following symptoms: Fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dark urine, light-colored stool, joint pain, and jaundice. Therefore, determining the etiology is based almost entirely on the patient's history and ancillary work-up. Possible etiologies include infectious agents, including the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), responsible for causing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), drug exposure, toxins, herbal supplements, and autoimmune and biliary causes. In the United Kingdom, United States, and Australia, the most common cause of acute hepatitis is acetaminophen-induced injury, which has a prevalence of 39%-50%[2]. However, in some cases, the etiology remains unknown or indeterminate. This may lead to a diagnosis of Acute Hepatitis of Unknown Origin (AHUO), which can emerge as a diagnostic and treatment challenge.

In today's literature, there is a paucity of data on ALI itself and much less information on AHUO in the adult population[1]. Instead, many cases of ALI are documented in the pediatric population, with some estimates suggesting that 30%-50% of cases have an unknown etiology[3]. Recently, the Centers for Disease Control has launched investigations into adenovirus-41 as a possible cause in children[4]. On the other hand, the incidence in adults varies by location and ranges between 11% and 75%[5-7], yet AHUO remains undefined in the literature for adults. It remains unknown if adenovirus-41 is a cause of AHUO in adults. There is only one Egyptian case report with this association[6]. Another important consideration is the effect of the COVID-19 vaccine on the liver, for which Chow et al[8] reported 32 cases of vaccine-induced autoimmune hepatitis.

Understanding the etiology is significant because it impacts the evaluation and management of the patient. Furthermore, after extensive history taking and common infectious and autoimmune causes are ruled out, the next steps to evaluate and manage the patient are unclear. Well-defined treatment guidelines do not currently exist. This is the scenario for the case report presented below. We present the case of an adult female with AHUO, describe our diagnostic approach, and discuss the treatment options. Our goal is to add to the body of literature that is currently limited on this subject and to provide our colleagues with a possible approach to caring for these patients.

A 58-year-old woman from Grenada presented with a chief complaint of nausea, vomiting, and jaundice after her primary care physician (PCP) discovered elevated LFTs on routine labs.

The patient had a 10-day history of fatigue, nausea, and intermittent non-bilious, non-bloody emesis. Four to five days before admission, she noticed that her eyes began to turn yellow, prompting her to visit her PCP. These symptoms were also associated with decreased appetite, weight loss of 10 lbs, and dark urine. She stated that she did not take her statin medication regularly, but she reported drinking a “green juice” for the past 3 d before admission. It consisted of watercress, garlic, and ginger. The patient denied abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, other changes in diet, or other use of supplements.

The patient’s past medical history was significant for chronic hypertension, non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia. There was no history of excessive alcohol use.

The patient denied any family history of liver disease or autoimmune disorders.

On admission, the patient was hypertensive (blood pressure 168/98 mmHg), tachycardic (heart rate 77 beats per min), and afebrile (37.1 C F). She was alert and oriented. No asterixis was noted in her upper extremities. She had mild bilateral scleral icterus. An abdominal exam revealed an overweight, non-distended, non-tender abdomen with no masses, no hepatomegaly, no flank tenderness, and no fluid wave.

The laboratory work-up showed: Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 2500 U/L (reference range 10-49 U/L), serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 3159 U/L (reference range 8-34 U/L), alkaline phosphatase 714 U/L (reference range 46-116 U/L), serum lipase 61 U/L (reference range 12-53 U/L), total bilirubin 6.4 mg/dL (reference range 0.3-1.2 mg/dL), direct bilirubin 4.4 mg/dL (reference range 0.1-0.3 mg/dL), prothrombin time 12.7 s, and INR 1.07. Table 1 portrays a trend from admission to discharge of pertinent values. Serological markers for hepatotropic viruses such as A, B, C, and E were all negative. She had no clinical signs of infection. Further infective work-up revealed negative serology for cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus 1 & 2, and human immunodeficiency virus. All tested autoantibodies, including antinuclear antibody (ANA), smooth muscle antibody, anti-mitochondrial antibody, liver soluble antibody, and anti-liver kidney microsome 1 antibody, were negative (Table 2 for all serological results). The patient was tested for Wilson’s disease, for which her ceruloplasmin levels came back as slightly elevated at 62 mg/dL. We attributed this to her current inflammatory state.

| Blood test | Day of admission | Day 5 | Day of discharge | Reference range |

| WBC × 109/L | 6.3 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 4.5-11 |

| Hgb (g/dL) | 13.7 | 12.6 | 11.9 | 12-16 |

| Platelets × 109/L | 348 | 293 | 276 | 130-400 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 9 | 8 | 7 | 9-23 |

| sCr. (mg/dL) | 0.87 | 0.72 | 0.68 | 0.55-1.02 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 6.4 | 4 | 3.6 | 0.3-1.2 |

| AST (U/L) | 3159 | > 1000 | 1775 | 8-34 |

| ALT (U/L) | 2500 | 2141 | 1903 | 10-49 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 714 | 563 | 486 | 46-116 |

| INR | 1.07 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.78-1.04 |

| Reference range | ||

| Ceruloplasmin | 62 mg/dL | 18-53 mg/dL |

| Transferrin | 362 mg/dL | 188-341 mg/dL |

| Acetaminophen | < 2.0 mcg/mL | 10-20 mcg/mL |

| HSV-1 IgM antibody | Negative | N/A |

| HSV- 2 IgM antibody | Negative | N/A |

| Mononucleosis screen | Negative | N/A |

| SMA titer screen | Negative | N/A |

| IgG | 2225 mg/dL | 600-1640 mg/dL |

| IgA | 394 mg/dL | 47-310 mg/dL |

| IgM | 241 mg/dL | 50-300 mg/dL |

| HBV surface antigen | Non-reactive | N/A |

| HBV core IgM | Non-reactive | N/A |

| HCV Antibody | Non-reactive | N/A |

| HCV RNA PCR quantitative | < 1.18 log IU/mL | N/A |

| HAV antibody IgM | Non-reactive | N/A |

| HEV antibody | Not detected | N/A |

| HIV 1/2 | Non-reactive | N/A |

| EBV IgM titer | <36 U/mL, negative | < 36 U/mL, negative |

| LKM IgG antibody | Negative | < 20.0 |

| Anti-mitochondrial antibody | Negative | Negative |

| SLA antibody | < 20.1 | 0.0-20.0 |

| ANA screen IFA | Negative | N/A |

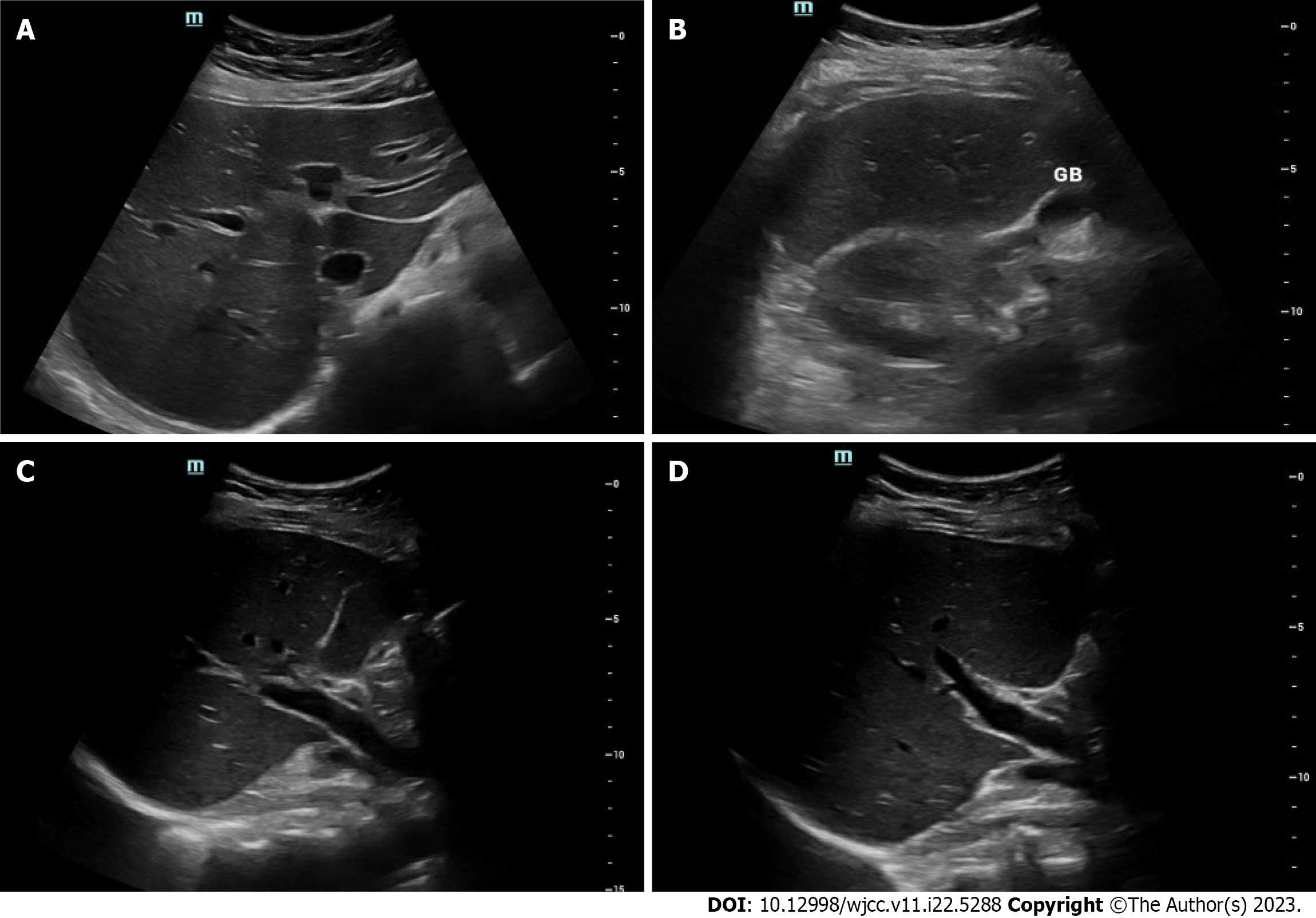

An abdominal ultrasound with Doppler showed no significant parenchymal abnormalities with normal arterial and venous Doppler of the liver and spleen. The gallbladder was contracted with no definite evidence of cholecystitis (Figure 1). A follow-up magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) with and without contrast was then conducted to rule out biliary causes of acute hepatitis (Figure 2). The MRCP showed a biliary system with no filling defects, stones, or ductal dilation. All other organs were within normal limits.

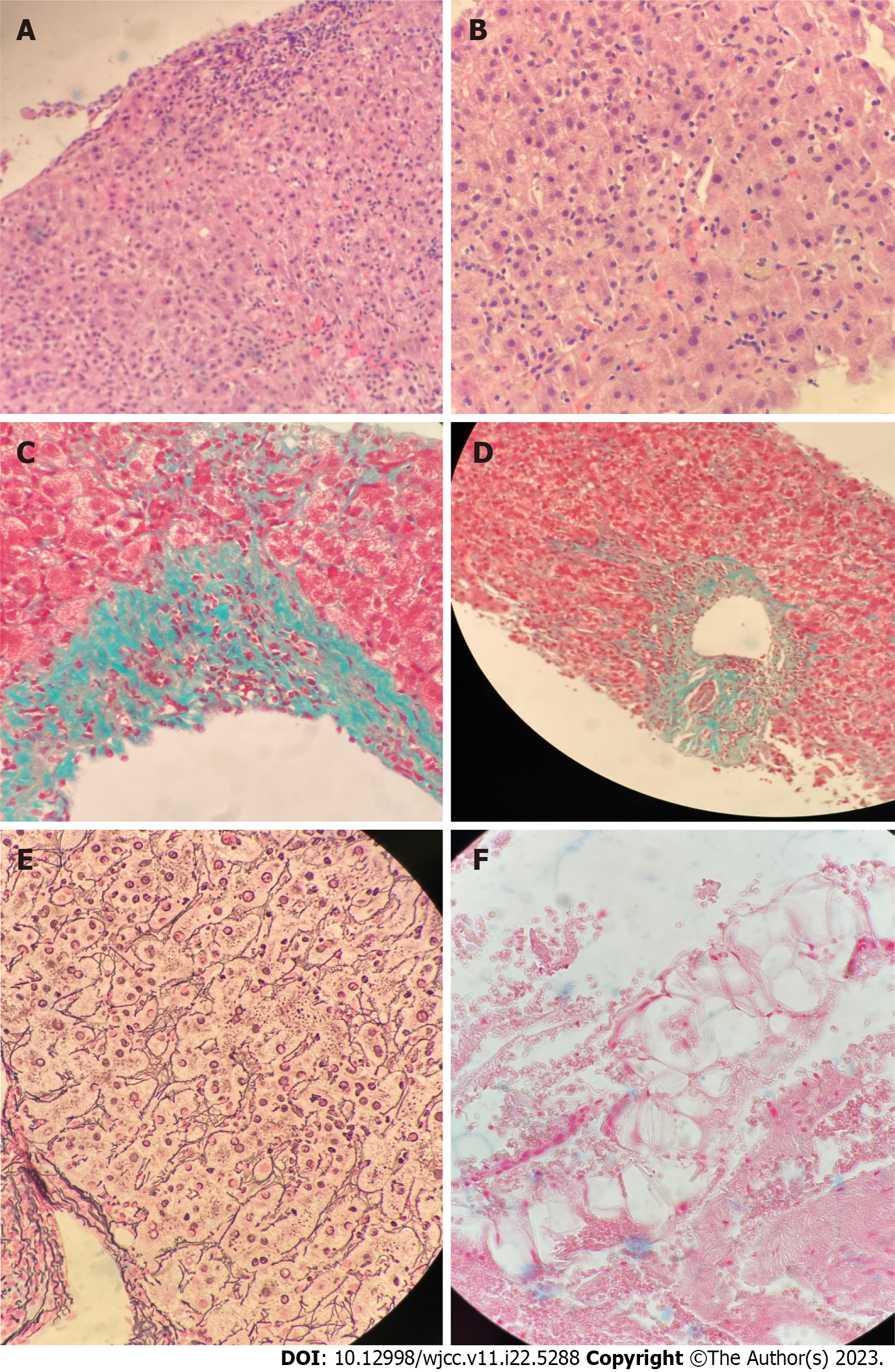

The patient underwent a liver biopsy, which showed moderate to severe active hepatitis with focal confluent necrosis, consisting mostly of lymphocytes with few eosinophils, plasma cells, and neutrophils with scattered acidophil bodies. Her biopsy was negative for cholestasis, granulomas, or malignancy (Figure 3). Differentials from the pathology report include drug/toxin/herbal/supplement-induced injury and infection (including viral hepatitis E), and less likely immune-mediated injury given negative autoimmune workup (negative ANA, anti-smooth muscle antibody, anti-mitochondrial antibody, anti-liver kidney microsome-1 antibody, and anti-soluble liver antigen antibody).

After a complete work-up by our team, including a core liver biopsy, the final diagnosis was AHUO.

During the admission, the patient was managed conservatively with IV fluids due to reported nausea and vomiting. We held her statin medication and stabilized her blood pressure.

The patient spent a total of 5 d in the hospital and was discharged on July 29th, 2022. After discharge, the patient was advised to follow up with gastroenterology in our outpatient clinic but was lost to follow-up.

We present the case of a middle-aged woman with ALI who underwent an extensive history and physical examination over several days accompanied by an extensive laboratory workup. Despite these efforts, we found no apparent reason for her ALI. In patients such as ours, they are often subject to a multitude of tests and procedures, multiple days of hospitalization, and many consults by medical professionals with varying opinions. Our case represents not only a diagnostic challenge but also presents a complicated treatment plan. We found the literature to be scant on idiopathic ALI in adults. This case report is an effort to add to the knowledge base of the scientific community.

Due to the lack of information on this topic, reported rates of incidence vary widely. In a study of 386 subjects with ALI, researchers found that 11% were considered to be of “indeterminate” causes; APAP toxicity was the cause of the majority of cases at 50%, while 12% was caused by autoimmune hepatitis[1]. A smaller Egyptian study of 42 patients (median age 34.55) reported an incidence rate of AHUO of up to 75%, of which most were male[6]. Although limited, the existing literature does highlight the importance of determining the etiology of ALI as it can be predictive of morbidity. Koch et al[1] reported that 93% of APAP-induced ALI would generally improve rapidly with a full recovery, while non-APAP patients carry a higher risk of poor outcomes; they suggest that early referral to a transplant center should be considered (2017).

At present, there are no established practice guidelines on AHUO. Treatment options depend on etiology and include fluid resuscitation, symptom management, anti-viral medication, corticosteroids or other immunomodulators, and avoidance of hepatotoxic substances[9]. The vast scope of these options, all with numerous adverse effects to consider, makes it difficult to treat AHUO. For our patient, we started with a complete history and physical exam, followed by laboratory tests to rule out common causes of acute hepatitis. Once the routine test results were inconclusive, we proceeded to investigate rarer causes of acute hepatitis, which included an autoimmune workup and, finally, a core liver biopsy. It is important to keep in mind that all lab tests are themselves subject to false negatives. In terms of treatment, we provided supportive care only and kept a close watch over her daily symptoms for fear that her AHUO would convert to fulminant hepatitis.

The liver biopsy confirmed the presence of necrosis, and the pathology report suggested a toxin-mediated or infectious cause rather than an immune-mediated etiology. Lab tests ruled out common infectious causes of ALI, including viral hepatitis. Thus, we could consider atypical causes of acute hepatitis, including the COVID-19 vaccine or the SARS-CoV-2 itself. In general, about 60% of those with acute COVID-19 infection will have abnormal LFTs, which are characterized by a gradual onset of lymphocytic infiltration within the liver parenchyma[10]. Multiple case reports exist that support the theory of SARS-CoV-2-induced acute liver injury[11,12]. These patients received a similar workup for acute hepatitis, yielding negative results, which led researchers to conclude that COVID-19 infection was the source of the ALI. This is an unlikely cause in our patient, who tested negative for acute SARS-CoV-2 infection on admission and was asymptomatic for COVID-19. She reported being vaccinated with the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine with two subsequent boosters. Unfortunately, our records do not indicate when she received these vaccines.

In terms of a vaccine-mediated etiology, an analysis of 18 cases of acute liver injury after vaccination with either the Comirnaty or Spikevax vaccines suggests that while still rare, it is certainly a possibility[13]. Moreover, several case reports exist that speculate an association between the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine and the development of acute hepatitis. For example, Ventura et al[14] describe the case of a 38-year-old woman who presented with acute hepatitis 2 wk after receiving the second dose of the Pfizer vaccine. The patient’s liver enzymes, as with ours, were very elevated (ALT 3769 U/L and AST 1572 U/L) and recovered with the administration of corticosteroids. Another case report by Palla et al[15] reported a case of acute hepatitis in a 40-year-old woman 1 wk after initial vaccination with the Pfizer vaccine. Similar to the other patient and ours, all labs for infectious and autoimmune etiologies were negative, except that their patient did have a positive ANA. Overall, since we do not know the timing of the vaccines for our patient, it is difficult to designate it as the culprit for her acute liver injury, but it should still be regarded as a possibility as the long-term effects of both the SARS-CoV-2 and its many vaccines are still unknown.

Due to the various possible etiologies, managing a patient with AHUO requires a multidisciplinary approach. In order to manage this patient, we included rheumatology and gastroenterology experts. The decision of whether or not to start corticosteroid therapy was discussed with the interdisciplinary team a few days after admission in response to worsening LFTs and the fear that her ALI would convert to fulminant hepatitis. Corticosteroid treatment for elevated LFTs includes etiologies such as autoimmune hepatitis. However, the patient was hesitant to be placed on steroids, and the treatment team decided against using corticosteroids due to a possible underlying infectious cause of acute liver injury as suggested by the biopsy. It is important to recognize that although an extensive workup for hepatitis may be non-revealing, we still cannot definitively rule out rare autoimmune causes or untested infectious causes.

While our case had many strengths, including sufficient details to examine AHUO in terms of workup and treatment plan, one major limitation was losing our patient to follow-up in the outpatient setting.

Looking ahead, researchers are continuously discovering etiologies of acute hepatitis using whole-genome sequencing (WES). In the Journal of Hepatology in 2019, Hakim and colleagues found that 25% of patients with AHUO analyzed using WES will yield an actionable result[16]. This is a promising prospect as we move into an era of personalized medicine.

AHUO has a fairly high incidence in the adult population with no defined treatment guidelines, leaving physicians feeling perplexed and patients feeling confused and unfulfilled, especially if a long hospitalization is required. Our case sheds light on this situation from workup to management. From our review of the literature and our own experience, we propose supportive treatment and watchful waiting. However, if the patient acutely worsens, steps for organ transplant should be taken. Furthermore, if the patient improves, management should be converted to the outpatient setting for patient satisfaction. Additionally, we suggest adopting a multidisciplinary approach, which may bring new perspectives and insights. A liver biopsy may help in the diagnosis but should be interpreted based on the clinical situation. Before discharge, our patient was educated about the benefits and side effects of possible steroid therapy. She was also informed about hepatotoxic medications and supplements to avoid. Continuation of care in an outpatient setting is appropriate if the patient is agreeable and adherent to the plan.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chuang WL, Taiwan; Mogahed EA, Egypt S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Argo CK, Caldwell SH. Editorial: Severe Acute Liver Injury: Cause Connects to Outcome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1397-1399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schaefer TJ, John S. Acute Hepatitis. 2022 Jul 18. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overview: Children with Hepatitis of Unknown Cause. [Online]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncird/investigation/hepatitis-unknown-cause/overview-what-to-know.html. |

| 4. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Alerts Providers to Hepatitis Cases of Unknown Origin. [Online]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2022/s0421-hepatitis-alert.html. |

| 5. | Brennan PN, Donnelly MC, Simpson KJ. Systematic review: non A-E, seronegative or indeterminate hepatitis; what is this deadly disease? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:1079-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ramadan HK, Sayed IM, Elkhawaga AA, Meghezel EM, Askar AA, Moussa AM, Osman AOBS, Elfadl AA, Khalifa WA, Ashmawy AM, El-Mokhtar MA. Characteristics and outcomes of acute hepatitis of unknown etiology in Egypt: first report of adult adenovirus-associated hepatitis. Infection. 2022;1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Salek J, Byrne J, Box T, Longo N, Sussman N. Recurrent liver failure in a 25-year-old female. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:1049-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chow KW, Pham NV, Ibrahim BM, Hong K, Saab S. Autoimmune Hepatitis-Like Syndrome Following COVID-19 Vaccination: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:4574-4580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mehta P, Reddivari AKR. Hepatitis. 2022 Oct 24. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Gadour E. Hassan Z. Shrwani K. COVID-19 Induced Hepatitis (CIH), Definition and Diagnostic Criteria of a Poorly Understood New Clinical Syndrome. Gut. 2020;69 (Suppl 1):. A22-A22. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wander P, Epstein M, Bernstein D. COVID-19 Presenting as Acute Hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:941-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bongiovanni M, Zago T. Acute hepatitis caused by asymptomatic COVID-19 infection. J Infect. 2021;82:e25-e26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pinazo-Bandera JM, Hernández-Albújar A, García-Salguero AI, Arranz-Salas I, Andrade RJ, Robles-Díaz M. Acute hepatitis with autoimmune features after COVID-19 vaccine: coincidence or vaccine-induced phenomenon? Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2022;10:goac014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Frank v, Jaison S J, Yamam I AS, Heather L S, Kashif K. Autoimmune hepatitis: Possible relation to the pfizer-biontech COVID-19 vaccine? Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:S1180-S1180. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Palla P, Vergadis C, Sakellariou S, Androutsakos T. Letter to the editor: Autoimmune hepatitis after COVID-19 vaccination: A rare adverse effect? Hepatology. 2022;75:489-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hakim A, Zhang X, DeLisle A, Oral EA, Dykas D, Drzewiecki K, Assis DN, Silveira M, Batisti J, Jain D, Bale A, Mistry PK, Vilarinho S. Clinical utility of genomic analysis in adults with idiopathic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2019;70:1214-1221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |