Published online Jul 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i21.5147

Peer-review started: May 8, 2023

First decision: May 31, 2023

Revised: June 3, 2023

Accepted: June 25, 2023

Article in press: June 25, 2023

Published online: July 26, 2023

Processing time: 79 Days and 18.7 Hours

Correcting severe skeletal class III malocclusion with facial asymmetry in adults through orthodontic treatment alone is difficult.

In this case report, we describe orthodontic treatment and lower incisor extraction without orthognathic surgery for a 27-year-old man with a transverse discre

After treatment, the patient had a more symmetrical facial appearance, acceptable overjet and overbite, and midline coincidence. The treatment results remained stable 3 years after treatment. This case report demonstrates that a minimally invasive treatment can successfully correct severe skeletal class III malocclusion with facial asymmetry.

Core Tip: Correction of severe skeletal class III malocclusion with facial asymmetry in adults through orthodontic treatment alone can be challenging. This case report demonstrates successful correction of a 27-year-old man's malocclusion with lower incisor extraction, intermaxillary elastics, improved super-elastic Ti-Ni alloy wire, and unilateral multibend edgewise arch wire. The use of these techniques, in conjunction with elastic chain closure of extraction sites, resulted in a more symmetrical facial appearance, acceptable overjet and overbite, and midline coincidence. This minimally invasive approach proved stable 3 years after treatment.

- Citation: Huang CY, Chen YH, Lin CC, Yu JH. Improved super-elastic Ti-Ni alloy wire for treating adult skeletal class III with facial asymmetry: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(21): 5147-5159

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i21/5147.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i21.5147

Facial symmetry has a positive influence on facial attractiveness ratings[1]. Ideal occlusion is related to the symmetry of the maxillofacial bone. Skeletal asymmetry results in malocclusion[2]. Congenital, environmental, functional, and other factors cause facial asymmetry[3]. Surgery is usually included in the treatment plan for patients with facial asymmetry[4]. The goal of such a treatment plan is a symmetrical dentofacial configuration with stable occlusion. In certain cases, extracting a lower incisor as a treatment alternative enables orthodontists to improve occlusion and esthetics with minimal orthodontic action[5]. Lower incisor extraction is clinically indicated in four specific scenarios: Anomalies related to the number of anterior teeth, tooth size discrepancies, ectopic eruption of incisors, and moderate class III malocclusions[6]. Class III malocclusions can be improved by shortening the length of the mandibular arch, which retrudes the position of the lower incisors. In the current case report, we describe the treatment of a man with skeletal class III malocclusion and facial asymmetry. Combined surgical and orthodontic therapy is often the treatment choice because of the satisfactory results and stability. However, alternative treatment choices are necessary in patients with severe problems who reject or are unwilling to accept surgery as a part of their treatment plans. Camouflage treatment with selective extraction is acceptable therapy, in which continuous light forces combined with extraction enable mild to moderate mandibular prognathism to be camouflaged by tipping tooth movements[7]. In this case, orthognathic surgery was avoided, minimizing the patient’s discomfort.

The individual seeking orthodontic treatment was a 27-year-old male patient who sought a consultation at China Medical University Hospital. During the initial visit, no specific medical issues or temporomandibular joint symptoms were noted. He presented with the chief complaint of poor dental alignment and thus visited the hospital for an esthetic consultation.

The patient does not have any specific illness or symptom.

The patient does not have any significant medical history or prior orthodontic treatment.

The patient does not have a family history of dental or orthodontic issues.

A class III molar relationship on the right and left was observed, as well as an anterior crossbite from the left canine to the right lateral incisor (Figure 1). The mandibular dental midline was deviated 3.3 mm to the left, and severe crowding between the mandibular anterior teeth was observed (Figure 2). The cant of the occlusal plane was minor. Manual lateral cephalometric analysis revealed an excessive lower incisor lingual inclination (Table 1).

| Measurements | Pretreatment | Posttreatment |

| SNA | 85.7° | 86.8° |

| SNB | 87.8° | 87.5° |

| ANB | -2.1° | -0.7° |

| FMA | 25.1° | 23.7° |

| U1 to FH plane | 121.2° | 121.8° |

| IMPA | 82.2° | 82.4° |

| Interincisal angle | 131.5° | 132.1° |

| Maxillary intercanine width (mm) | 33.2 | 86.8 |

| Mandibular intercanine width (mm) | 55.2 | 55.7 |

| Maxillary intermolar width (mm) | 25.3 | 31.7 |

| Mandibular intermolar width (mm) | 46.7 | 44.5 |

| Left ramus | 7° | 9° |

| Right ramus | 10° | 10.5° |

He had a skeletal class III jaw (a point-nasion-b point angle ≤ 0°), class III molar relationship (lower molar positioned mesially relative to the upper molar, with no specifications regarding the line of occlusion)[8], and facial asymmetry, with the chin deviating to the left.

This functional shift of the mandible caused mandibular asymmetry, which was observed in panoramic and post

The major problems were summarized as frontal asymmetry, deviation of the chin, anterior crossbite, mandibular anterior crowding, and mandibular dental midline deviation. Additionally, the patient had a slight transverse centric occlusion-centric relation discrepancy.

Treating facial asymmetry and anterior crossbite solely with orthodontic methods can be challenging. As a result, our initial treatment plan involved a combination of orthodontic treatment and orthognathic surgery. The proposed treatment plan involved extracting the maxillary third molars, aligning the maxillary and mandibular arches, and closing the space in the mandibular arch as a preliminary step in the presurgical orthodontic treatment. Subsequently, orthognathic surgery would be performed to correct the chin and mandible asymmetries. After the surgery, postsurgical orthodontic treatment would be implemented to address the malocclusion. While this plan offered the benefit of addressing the patient's skeletal asymmetry, it is important to acknowledge that it carried inherent surgical risks and financial implications.

The alternative treatment plan involved orthodontic treatment without the need for orthognathic surgery. It was proposed to extract the maxillary third molars and one mandibular incisor to address the occlusal interference responsible for the mandibular shift and subsequent facial asymmetry. By correcting the occlusal discrepancy, we aimed to achieve a more symmetrical facial profile through orthodontic means alone. This plan offered the advantage of avoiding surgical intervention, reducing associated risks, and potentially minimizing the financial burden on the patient[9]. To address the remaining facial asymmetry and achieve optimal treatment outcomes, intermaxillary elastics (IME) traction using 3M Unitek Elastics (3.5 oz, United States) would be implemented. The elastics would be placed over the lower left molar to induce mandibular clockwise rotation and contribute to the extrusion of the molars. The use of IMEs as part of the orthodontic treatment aimed to establish a connection between the upper and lower teeth. This approach would lead to improved vertical control, reduced anterior overjet, and correction of the facial asymmetry. By minimizing the reliance on surgery, this plan sought to reduce the treatment burden while maximizing the reduction of asymmetry. However, it should be noted that complete elimination of the asymmetry may be challenging to achieve with this approach. The patient made the decision to proceed with the second treatment plan, which involved orthodontic treatment without orthognathic surgery. This choice was based on his preference to avoid undergoing surgical intervention.

Initial leveling progressed with 0.016-inch × 0.022-inch improved super-elastic Ti-Ni alloy wire (ISW) (Figure 4A-C). The extraction sites were closed using IME, which generated a canine distal driving force to retract the anterior teeth. An elastic chain was used to close the anterior space. The space was closed after 4 mo of leveling and elastic traction. Distalization of the mandibular left molars was planned to improve the molar relationships and the mandibular dental midline. The mandibular left posterior teeth were distalized using an ISW unilateral multibend edgewise arch wire (MEAW). For midline correction, IMEs were applied from the maxillary right canine to the mandibular right second premolar and from the maxillary left second premolar to the mandibular left first premolar (Figure 4D-F). For correcting the facial asymmetry, IMEs were then used from the maxillary right canine to the mandibular right canine and from the maxillary left first premolar to the mandibular left first molar (Figure 4G-I).

The midline deviation and facial asymmetry were improved considerably after 12 mo of active treatment. A plain wire was used over the lower arch for leveling. The maxillary left second premolar was rebonded for derotation (bonding: Orthomite LC Kit, Sun Medical, Japan). The archwire was not engaged into the bracket slot (plastic bracket: Esther II, TOMY Inc., Japan) but rather above the bracket of the maxillary left canine for intrusion (not-in-slot; Figure 5). Figure 5 was created using PowerPoint (Microsoft 365, version 16.57, Microsoft, United States).

Active treatment was successfully completed after 20 mo, and all fixed orthodontic appliances were removed. Circumferential retainers (retainers, JIA HUI dental lab, Taichung, Taiwan) were fitted onto the maxillary arch, while a Hawley retainer was placed on the mandibular arch. The patient was instructed to wear the retainers full-time for the initial 3 mo and then transition to nighttime wear for a minimum of 2 years.

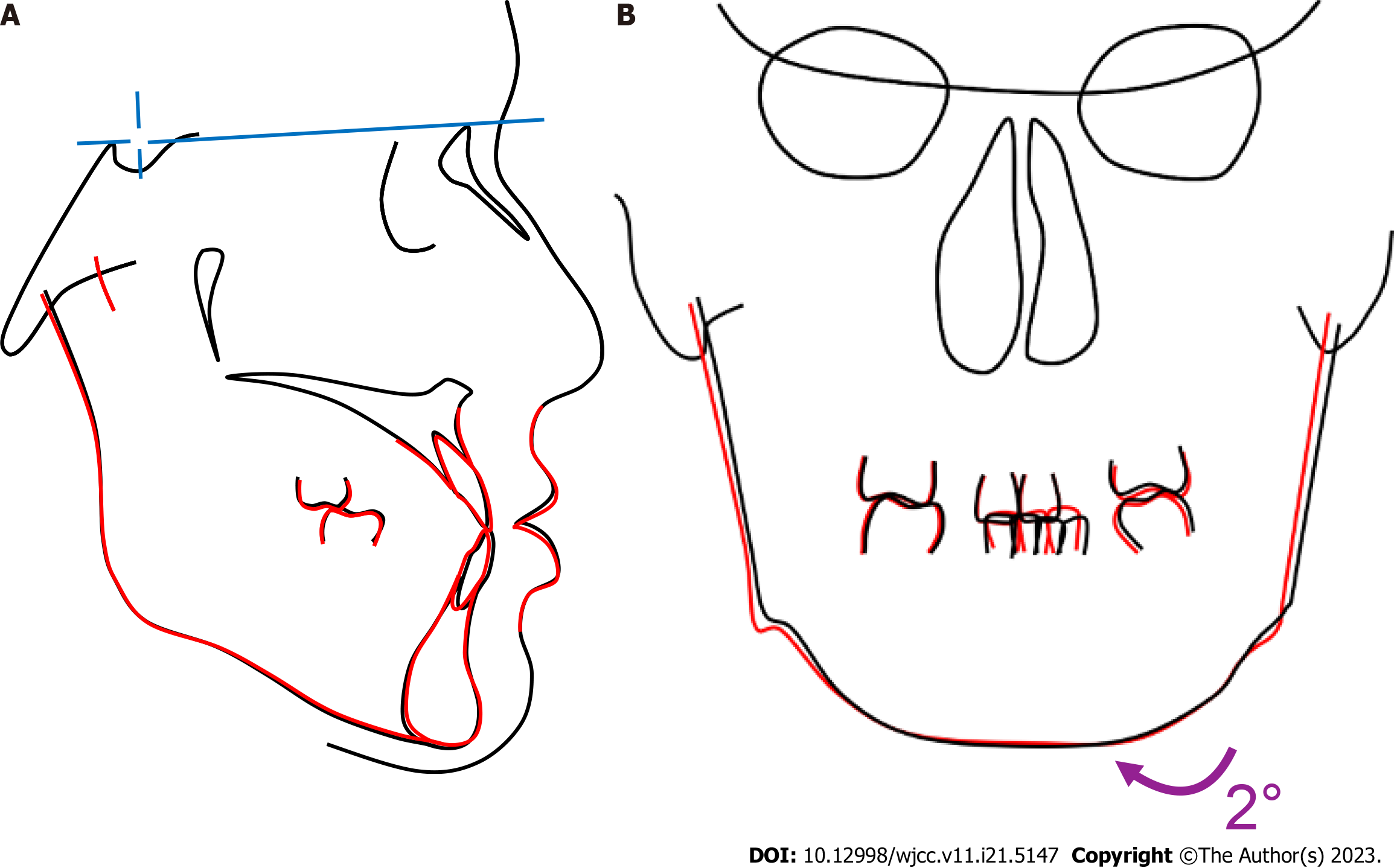

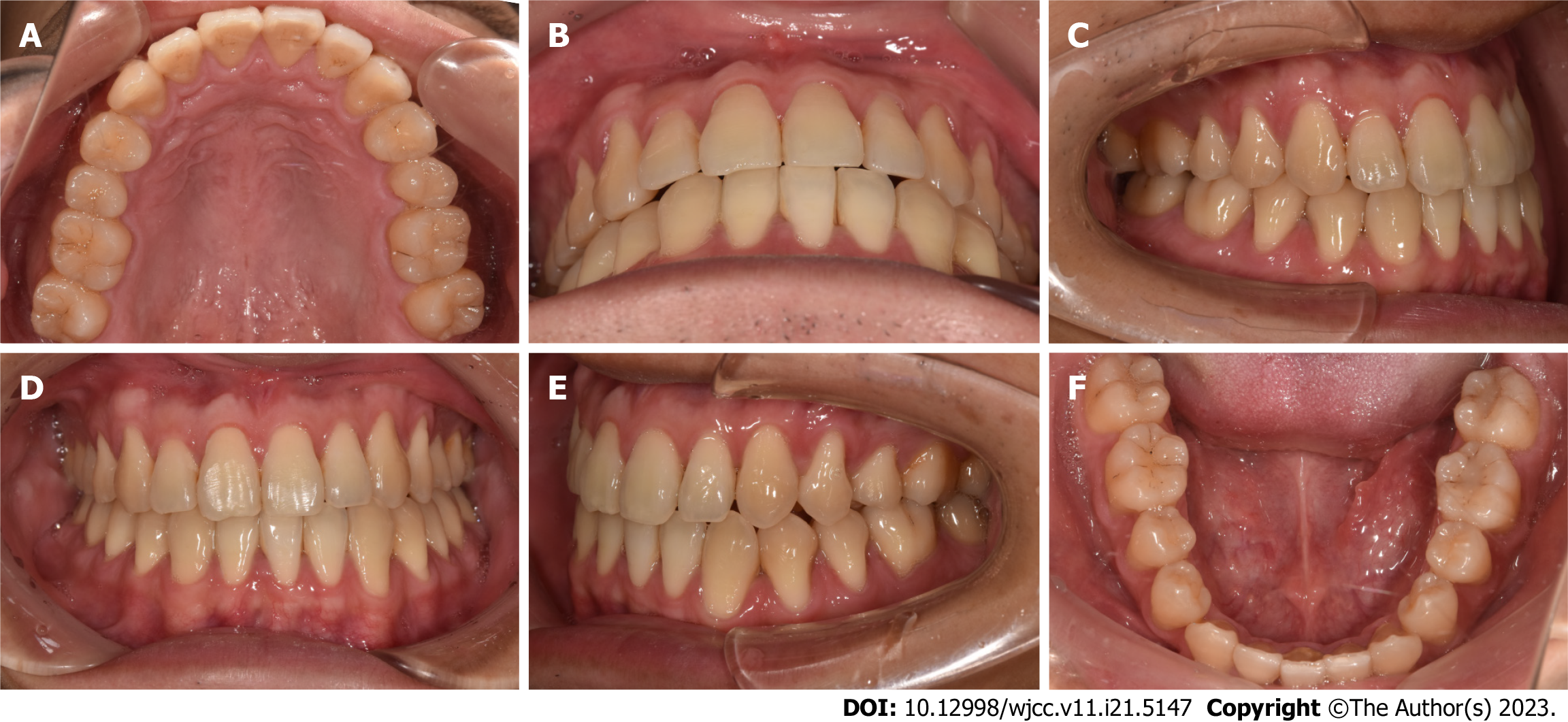

The final records (Figures 6-8) revealed that the anterior crossbite was corrected and that the dental midline was coincident after lower right canine substitution with the lateral incisor. The space in the mandibular arch was closed, and the moderate-to-severe crowding of the mandibular arch was relieved. The skeletal facial asymmetry was partly resolved through the recovery of the mandibular functional shift. Distalization of the mandibular left posterior teeth was performed, which contributed to the achievement of an acceptable overjet and overbite relationship. Panoramic radiographs showed that the teeth had well-aligned parallel roots, and no signs of root resorption were detected. A comparison of the measurements before and after treatment (Table 1) revealed a decrease in the Frankfort-mandibular plane angle, resulting in distalization through the ISW unilateral MEAW. Furthermore, normalization of the inclination of the mandibular anterior teeth was accomplished through space closure. A comparison of the dental casts before and after treatment (Table 1) revealed that the maxillary intercanine and intermolar widths increased by 3.0 mm and 0.5 mm, respectively. Moreover, the mandibular intercanine width increased by 6.0 mm with the substituted canine and the right first premolar, and the intermolar widths decreased by 2.0 mm. Frontal cephalometric radiographs showed coincidence of the dental midline. Minor movement of the mandibular condyle was also observed while correcting the functional shift. Superimposition of the lateral cephalometric radiographs showed the distalization of the mandibular molars and the mesialization of the maxillary molars (Figure 9).

The patient returned for reevaluation at 1, 2 and 3 years after debonding (Figures 10-12). His occlusion was well maintained, and the occlusal relationships of the premolars and molars were maintained.

The crucial part of the mandibular anterior crowding and anterior crossbite caused further esthetic concern in the patient. Therefore, for correcting the anterior crossbite, the first treatment plan included flaring out the maxillary anterior teeth. However, in patients with severe mandibular anterior crowding, such as the patient described in the case report, leveling the mandibular teeth and flaring out the maxillary teeth may cause the lips to protrude and produce a convex facial profile. To address this, tooth extraction was considered as an alternative to achieve better profile and arch coordination and alleviate the discrepancy.

Determining the extraction sites is critical when developing orthodontic treatment plans. Extracting a single mandi

Asian patients tend to be more resistant to surgical and invasive treatments, and many Asian patients reject miniscrews as a treatment option. In the current case, if the patient had elected to not undergo tooth extraction, utilizing mandibular miniscrews to provide anchorage and achieve distal movement of the lower teeth may have effectively addressed crowding and crossbite issues. The decision to not use miniscrews or surgery was influenced by the patient’s acceptance and preference. Because a nonsurgical approach was used to treat class III malocclusion in our patient, we attempted to decrease the initial overall ratio to improve the arch coordination. After extracting the right mandibular incisor, well-aligned dentition and thus better occlusion were achieved. However, if the mandibular incisor extraction is performed without careful planning, the resulting occlusal discrepancy often cannot be resolved satisfactorily. Drs. Kokich and Shapiro[5] described that tooth-size analysis should be performed when planning mandibular incisor extraction. Based on the Bolton ratio[11], our measurements were as follows: Anterior ratio = 82.50% and overall ratio = 97.20%. After extracting the mandibular incisor, the measurements were as follows: Anterior ratio = 70.52% and overall ratio = 91.40%. In this case, an improved overbite and overjet were achieved by 3 incisor finish.

In clinical practice, malocclusions with discrepancies are often seen between dental and facial midlines. Therefore, it is imperative to determine the size of dental and facial midline discrepancies that is acceptable and unlikely to adversely affect dentofacial esthetics. Discrepancies of 2 mm or more are likely to be noticed[12]. One of the orthodontic treatment objectives should, when possible, be to correct the dental midline to within 2 mm of the facial midline. Our patient presented with 3.3 mm of midline shifting. For space closure, an elastic chain was placed over the lower arch, with the space resulting from the extracted mandibular incisor. Moreover, to distalize the left posterior teeth, the ISW unilateral MEAW was placed over the lower arch. IME was applied for midline adjustment.

The ISW possess unique characteristics that offer considerable potential for orthodontic appliances. ISWs offer 3 main valuable properties: Super-elasticity, shape memory, and shock and vibration absorption. Dr. Iramaneerat et al[13] in 2004 reported that the high damping capacity of the ISW can buffer the transmission of occlusal forces to the periodontal ligament. The transmission of lighter forces to the tooth roots leads to reduced patient discomfort and minimizes the occurrence of root resorption[14]. In the current study, using ISW unilateral MEAW, we effectively tipped the mandibular molars distally without extrusions and tipped the lower incisors lingually to camouflage skeletal class III malocclusions. The MEAW technique and use of modified class III elastics are an appropriate treatment strategy, especially for patients with a high angle and open bite tendency[15]. By combining the IME technique with the MEAW technique, we were able to achieve similar effects to those achievable when the MEAW technique is used in conjunction with miniscrews. In cases where the patient rejects miniscrews, we employ the IME technique along with the MEAW technique to achieve distal movement of the posterior teeth and create space to relieve dental crowding. The advantage of using the MEAW technique is that in addition to distal movement of the teeth, it has an intrusion effect, helping to avoid an increase in the mandibular plane angle. The treatment has been completed without the use of miniscrews, which avoids the risks of root injuries[16], failure[17], or fracture[18].

There are some limitations in the present case. Due to the extraction of the mandibular central incisor, the position of the dental midline was compromised. Instead of setting the midline in the middle of the crown of the other central incisor, we positioned the right lateral incisor and the left central incisor because of the right canine substitution with the lateral incisor. This was done to create a visual impression of midline alignment when the patient smiles to satisfy the patient’s aesthetic expectations. However, this approach has the drawbacks of causing asymmetry in the dental arch and a limited capacity to achieve perfect arch coordination.

In this case, the facial asymmetry was corrected considerably. The use of IME and the ISW unilateral MEAW was vital for solving the minor cant of the occlusal plane and for correcting the facial asymmetry. A more harmonious smile arc was achieved at the end of the treatment. Through superimposition of the frontal cephalograms (Figure 11), we found that his mandible had shifted to the right side, and that his facial appearance had improved considerably (Table 1). Consequently, the patient was satisfied with the treatment outcomes and pleased with the esthetic changes in his facial appearance.

The patient presented with minor facial asymmetry and severe mandibular anterior crowding. A successful treatment approach involved the extraction of one lower incisor, along with the application of unilateral MEAW and the not-in-slot technique. By using the ISW with the MEAW and IME, we successfully relieved the mandibular anterior crowding and anterior crossbite and achieved an adequate overbite and overjet. In patients with class III facial asymmetry, treatment options other than orthognathic surgery should be considered for achieving a functional shift because orthognathic surgery may not be necessary in these patients. For individuals with mild facial asymmetry and significant mandibular anterior crowding, a minimally invasive treatment approach can be considered. Although we cannot claim that an ideal overjet and overbite relationship was achieved in this case, despite the patient’s refusal to undergo surgery, we were able to achieve a result that both the patient and the doctor could accept through simple orthodontic treatment without the assistance of miniscrews.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cho SY, China; Scribante A, Italy S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Grammer K, Thornhill R. Human (Homo sapiens) facial attractiveness and sexual selection: the role of symmetry and averageness. J Comp Psychol. 1994;108:233-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 690] [Cited by in RCA: 554] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fukaya S, Kanzaki H, Miyamoto Y, Yamaguchi Y, Nakamura Y. Possible alternative treatment for mandibular asymmetry by local unilateral IGF-1 injection into the mandibular condylar cavity: Experimental study in mice. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;152:820-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bishara SE, Burkey PS, Kharouf JG. Dental and facial asymmetries: a review. Angle Orthod. 1994;64:89-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sekiya T, Nakamura Y, Oikawa T, Ishii H, Hirashita A, Seto K. Elimination of transverse dental compensation is critical for treatment of patients with severe facial asymmetry. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:552-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kokich VG, Shapiro PA. Lower incisor extraction in orthodontic treatment. Four clinical reports. Angle Orthod. 1984;54:139-153. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Canut JA. Mandibular incisor extraction: indications and long-term evaluation. Eur J Orthod. 1996;18:485-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lin J, Gu Y. Preliminary investigation of nonsurgical treatment of severe skeletal Class III malocclusion in the permanent dentition. Angle Orthod. 2003;73:401-410. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Peracini A, Andrade IM, Paranhos Hde F, Silva CH, de Souza RF. Behaviors and hygiene habits of complete denture wearers. Braz Dent J. 2010;21:247-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ko EW, Huang CS, Chen YR. Characteristics and corrective outcome of face asymmetry by orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2201-2209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Faerovig E, Zachrisson BU. Effects of mandibular incisor extraction on anterior occlusion in adults with Class III malocclusion and reduced overbite. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;115:113-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bolton WA. Disharmony in tooth size and its relation to the analysis and treatment of malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 1958;28:113-130. |

| 12. | Johnston CD, Burden DJ, Stevenson MR. The influence of dental to facial midline discrepancies on dental attractiveness ratings. Eur J Orthod. 1999;21:517-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Iramaneerat K, Hisano M, Soma K. Dynamic analysis for clarifying occlusal force transmission during orthodontic archwire application: difference between ISW and stainless steel wire. J Med Dent Sci. 2004;51:59-65. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Middleton J, Jones M, Wilson A. The role of the periodontal ligament in bone modeling: the initial development of a time-dependent finite element model. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;109:155-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | He S, Gao J, Wamalwa P, Wang Y, Zou S, Chen S. Camouflage treatment of skeletal Class III malocclusion with multiloop edgewise arch wire and modified Class III elastics by maxillary mini-implant anchorage. Angle Orthod. 2013;83:630-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Montasser MA, Scribante A. Root Injury During Interradicular Insertion is the most Common Complication Associated with Orthodontic Miniscrews. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2022;22:101688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Xin Y, Wu Y, Chen C, Wang C, Zhao L. Miniscrews for orthodontic anchorage: analysis of risk factors correlated with the progressive susceptibility to failure. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2022;162:e192-e202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sfondrini MF, Gandini P, Alcozer R, Vallittu PK, Scribante A. Failure load and stress analysis of orthodontic miniscrews with different transmucosal collar diameter. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2018;87:132-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |