Published online Jul 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i21.5115

Peer-review started: February 22, 2023

First decision: April 26, 2023

Revised: May 28, 2023

Accepted: July 3, 2023

Article in press: July 3, 2023

Published online: July 26, 2023

Processing time: 154 Days and 13.2 Hours

Mirizzi syndrome is an uncommon clinical complication for which the available treatment options mainly include open surgery, laparoscopic surgery, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), electrohydraulic lithotripsy, and laser lithotripsy. Here, a patient diagnosed with type I Mirizzi syndrome was treated with electrohydraulic lithotripsy under SpyGlass direct visualization, which may provide a reference to explore new treatments for Mirizzi syndrome.

This paper describes a middle-aged female patient with suspected choledocholithiasis who complained for over 1 mo of intermittent abdominal pain, dark yellow urine, jaundice, and was proposed to undergo ERCP lithotomy. Mirizzi syndrome was found during the operation and confirmed by SpyGlass. Electrohydraulic lithotripsy was performed under the direct vision of SpyGlass. After the lithotripsy, the stones were extracted using the stone extraction basket and balloon. After the operation, the patient developed transient hyperamylasemia. Through a series of symptomatic treatments (such as fasting, fluids and anti-inflammation medications), the symptoms of the patient improved. Finally, laparoscopic cholecystectomy or open cholecystectomy was performed after a half-year post-operatively.

Direct visualization-guided laser or electrohydraulic lithotripsy with SpyGlass is feasible and minimally invasive for type I Mirizzi syndrome without apparent unsafe outcomes.

Core Tip: Mirizzi syndrome was traditionally treated with standardized open surgery and laparoscopic surgery. Recently, some less invasive alternative technologies (such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography stone extraction and medical electrohydraulic or laser lithotripsy) are gaining attention. This study reported a clinical case of SpyGlass-confirmed Mirizzi syndrome that was successfully treated by electrohydraulic lithotripsy under direct vision.

- Citation: Liang SN, Jia GF, Wu LY, Wang JZ, Fang Z, Wang SH. Type I Mirizzi syndrome treated by electrohydraulic lithotripsy under the direct view of SpyGlass: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(21): 5115-5121

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i21/5115.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i21.5115

Mirizzi syndrome is an uncommon clinical syndrome characterized by stenosis or obstruction of the common hepatic duct or common bile duct due to stones incarcerated in the cystic duct or the neck of the gallbladder, and internal fistulas from the gallbladder into the common bile duct, common hepatic duct, and duodenum which can develop with progression[1]. Traditionally, Mirizzi syndrome is mainly treated with standardized open surgery or minimally invasive laparoscopic approaches. In recent years, other less invasive alternative techniques have been tried, including endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), electrohydraulic lithotripsy, and laser lithotripsy[2]. This report describes a case of Mirizzi syndrome confirmed by SpyGlass and successfully treated by electrohydraulic lithotripsy under a direct view.

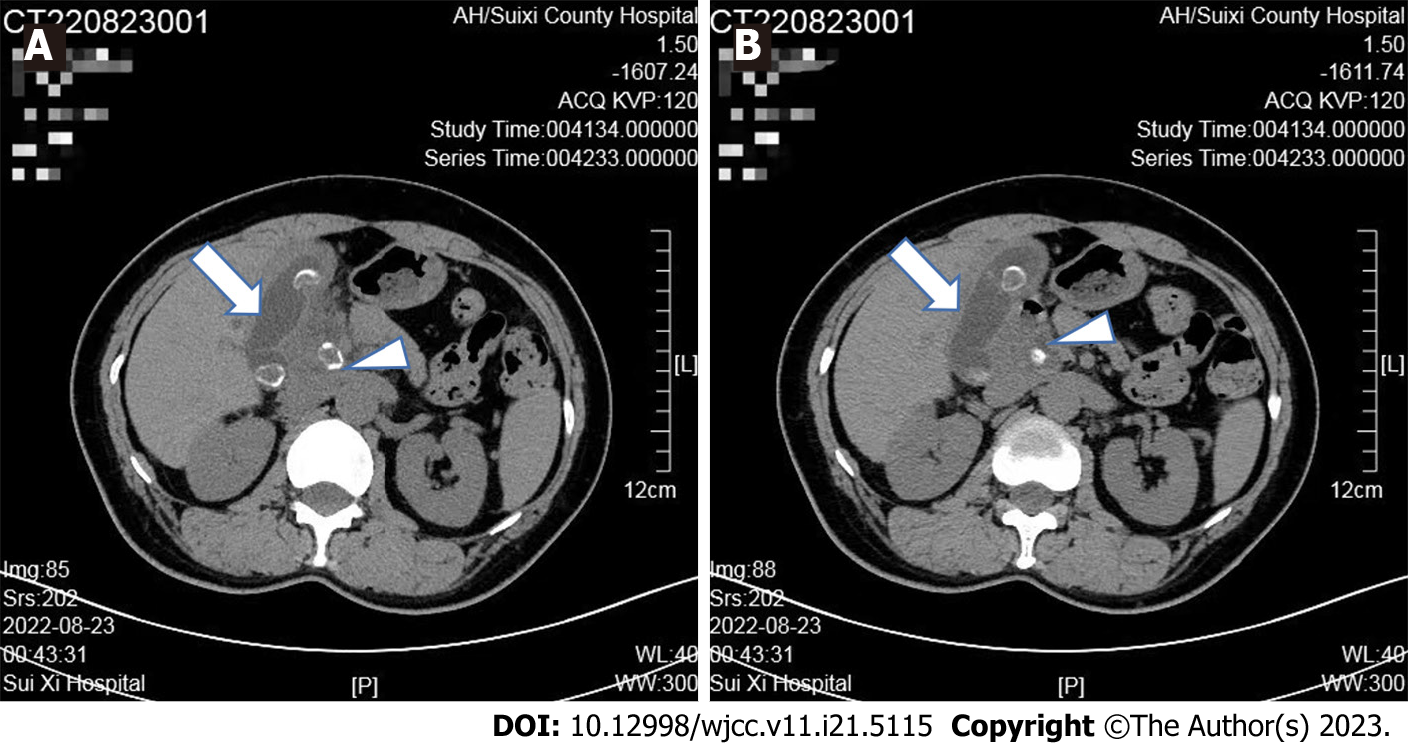

A 45-year-old female patient was admitted to the hospital because of over 1 mo of intermittent abdominal pain and 4 d of dark yellow urine and jaundice. The patient suffered from unexplained intermittent epigastric pain 1 mo ago, accompanied by nausea, vomiting, acid regurgitation, and heartburn, without chills or fever. Then, the dark yellow urine appeared 4 d ago and progressively worsened, without clay-colored stools. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) in another hospital suggested: (1) Stones in the retroduodenal segment of the common bile duct causing dilation of the bile duct above stone incarceration; and (2) Multiple stones in the gallbladder resulting in cholecystitis. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) (Figure 1) in another hospital showed: (1) Stones at the junction of the common hepatic duct and gallbladder? and (2) Multiple stones in the gallbladder leading to cholecystitis.

This patient had a history of post-cesarean complications for over 20 years.

She also had a history of arterial hypertension for 10 years and therefore had been taking oral felodipine.

This patient had a history of post-cesarean complications for over 20 years. Additionally, she also had a history of arterial hypertension for 10 years and therefore had been taking oral felodipine.

Physical examination revealed clear consciousness, stable vital signs, old surgical scars in the abdomen, soft whole abdomen, epigastric tenderness (+), no rebound tenderness, no palpable enlargement of the liver, spleen or subcostal area and negative Murphy sign.

The major test results were shown as follows: The routine blood test demonstrated leukocytes of 5.93 × 109/L and a neutrophil percentage of 76.5%. Comprehensive metabolic panel results exhibited 136 mmol/L sodium ↓, 56 μmol/L creatinine, 37 U/L creatine kinase ↓, and 3.36 mmol/L potassium ↓. The liver function test showed 171.8 μmol/L total bilirubin ↑, 138.9 μmol/L direct bilirubin ↑, 36.3 g/L albumin ↓, 165 U/L alanine aminotransferase ↑, and 106 U/L aspartate aminotransferase ↑. After admission, the patient was diagnosed with the following diseases: (1) Acute calculous cholecystitis; (2) Choledocholithiasis? (3) Mirizzi syndrome? and (4) Obstructive jaundice.

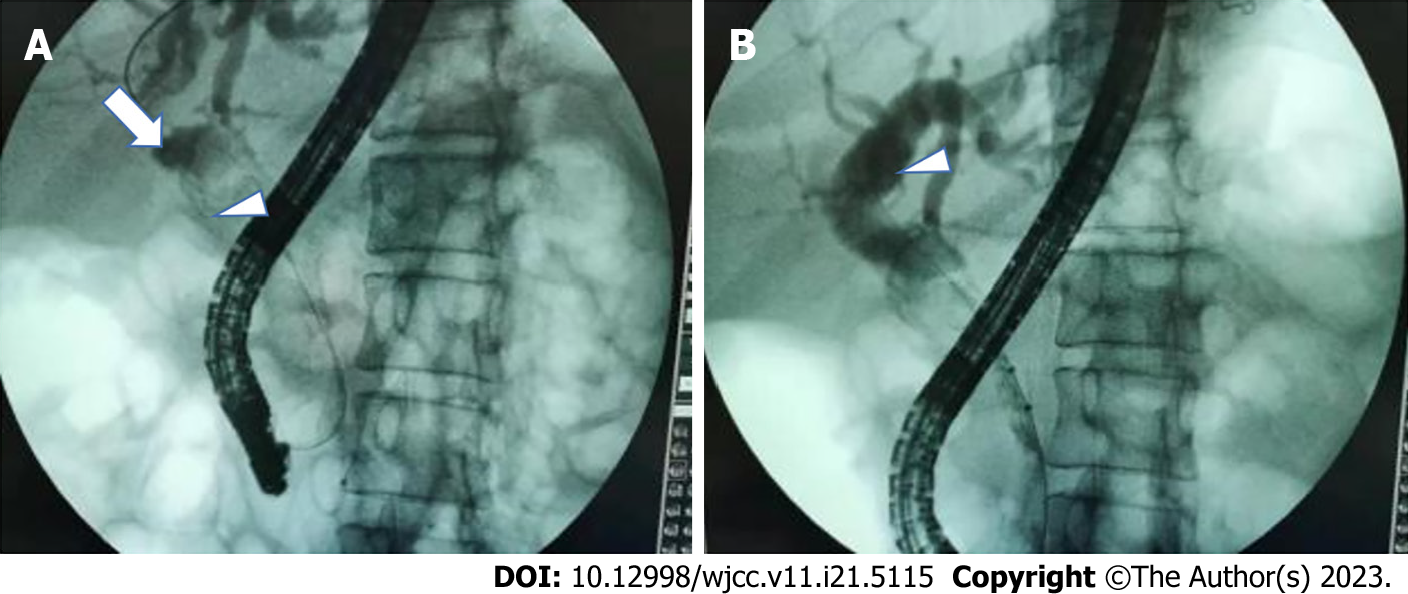

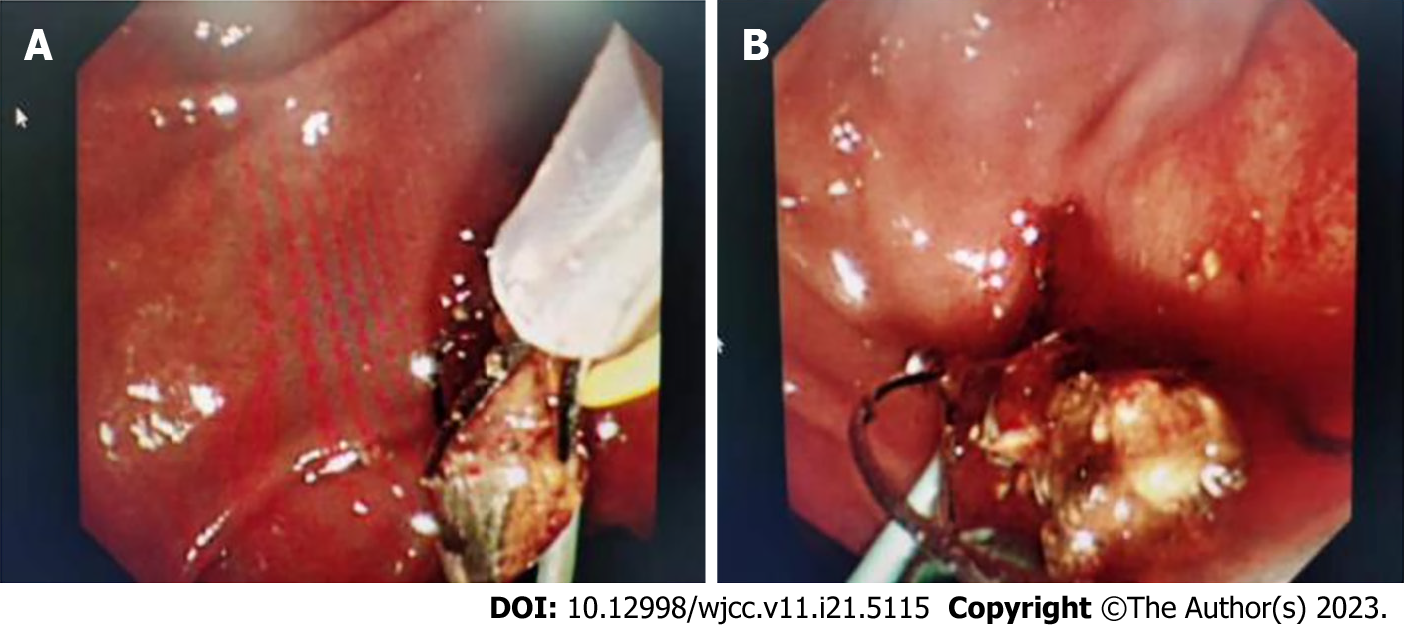

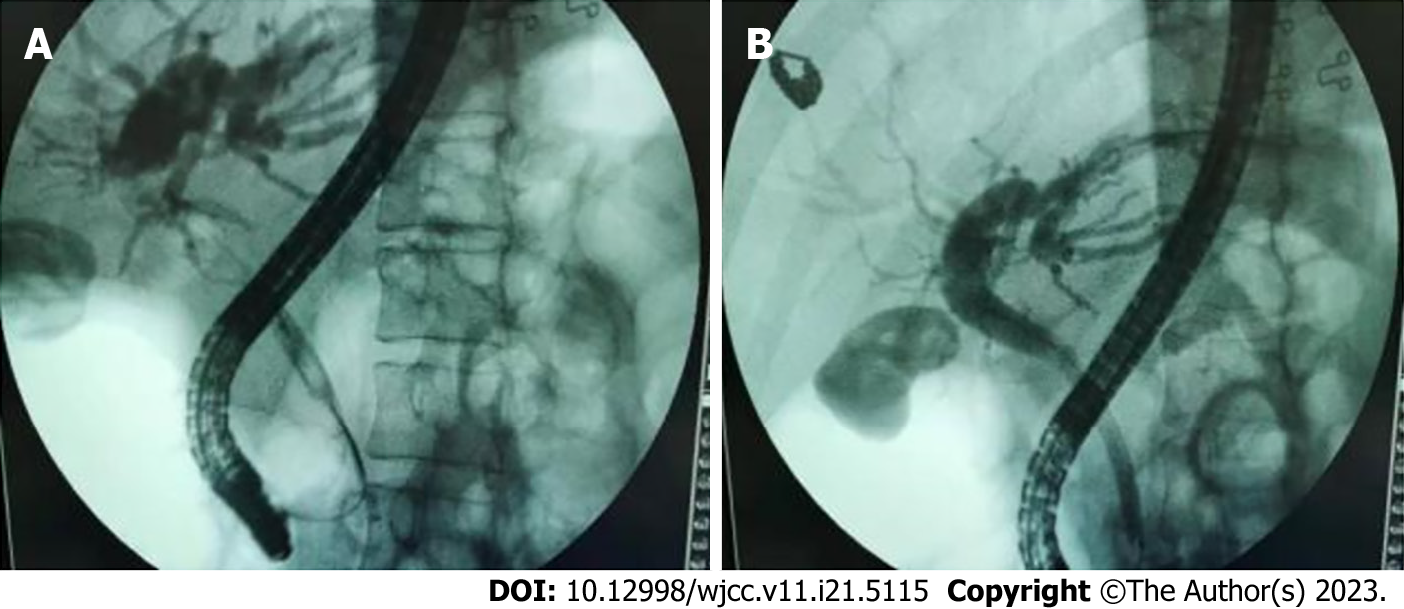

The patient was given symptomatic treatment such as acid suppression, anti-inflammation medications, fluid infusion, and stabilization of water and electrolytes. The patient underwent endoscopic sphincterotomy and balloon dilation under endoscopic retrograde cholangiography at our endoscopy center 2 d later, because she presented with jaundice and abnormal bilirubin and liver enzymes, suggesting extrahepatic biliary obstruction, with ERCP indications. Intraoperatively, villous papillary openings were observed, and the bile ducts were successfully super selected with an incision knife and guide wire and contrasted. The bile ducts were visualized. X-rays exhibited that the upper segment of the common bile duct was dilated with a diameter of about 1.4 cm, accompanied by dendritic dilation of the common hepatic duct and intrahepatic bile duct. In addition, it was also observed that an oval filling defect shadow existed at the junction of the cystic duct and common hepatic duct and moved, up to about 1.2 cm, and that the junction of the cystic duct was narrowed. The main pancreatic duct was not visualized, and the gallbladder was visualized with multiple filling defect shadows (Figure 2). Endoscopic sphincterotomy was conducted along the guide wire with an incision diameter of approximately 0.5 cm. After dilation with a columnar balloon of 1.0 cm in diameter, the stone impacted in the cystic duct partially went out into the lumen of the common bile duct under the direct view of the SpyGlass choledochoscope, and then electrohydraulic lithotripsy was performed under direct view (Figure 3). After lithotripsy, the stones were re

Mirizzi syndrome with cystic duct stones; stricture at the junction of the cystic duct and common hepatic duct (inflammatory considered). The patient had no abdominal pain, fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, panic, or chest tightness, with occasional abdominal distension and gradually resolved jaundice.

Then, a naso-biliary drainage tube was placed, and the biliary obstruction was completely resolved. In addition, a pancreatic duct stent was placed prophylactically. The patient was postoperatively diagnosed with acute calculous cholecystitis complicated by Mirizzi syndrome (type I) with cystic duct stones and obstructive jaundice. After the operation, her liver function indicators such as bilirubin gradually decreased. However, the patient developed transient hyperamylasemia of 697 μ/L at 4 h post-operatively, without abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and other symptoms. After the patient was treated with symptomatic treatments including fasting, fluids and anti-inflammation medications, the blood amylase gradually decreased to normal, and the patient was discharged from the hospital on the 5th d post-op.

Six months later, the patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy without complications.

Mirizzi syndrome, an uncommon complication of gallbladder stones, was systematically described and officially named by the Argentine surgeon Pablo Luis Mirizzi in 1948. This disease accounts for approximately 1% of gallbladder stones. The typical manifestations of Mirizzi syndrome were as follows: (1) The cystic duct is closely parallel to the common hepatic duct; (2) The gallbladder stone is incarcerated in the Hartmann's pouch or cystic duct; (3) Mechanical compression is secondary to gallbladder stones or induced by surrounding inflammation, which leads to obstruction of the common hepatic duct; and (4) Jaundice and recurrent inflammation cause a fistula between the gallbladder and common hepatic duct.

Mirizzi syndrome has been variously typed by McSherry in 1982, Csendes in 1989, Nagakawa in 1997, Beltran in 2008, Cesar in 2009, and Beltran in 2012. Among them, the team of Beltran further modified the typing proposed by Csendes, that is, the currently relatively recognized five types worldwide: type I, Mirizzi syndrome prototype; type II, combination with gallbladder-bile duct fistulas, with stone obstruction of less than 1/3 of the bile duct or fistula opening of less than 1/3 of the bile duct circumference; type III, gallbladder-bile duct fistulas, with stone obstruction of more than 2/3 of the bile duct or fistula opening reaching 2/3 of the bile duct circumference; type IV, gallbladder-bile duct fistulas, with complete obstruction of the bile duct by stones, complete destruction of the bile duct wall in a circular pattern, and fusion of the gallbladder and bile duct without discernible and dissectible layers between the two; type V, a combination of cholecystobiliary fistula with cholecystoenteric fistula, with or without gallstone ileus[3]. Furthermore, Morelli et al[4] reported 3 cases of Mirizzi Syndrome and concluded that Mirizzi syndrome should be classified as acute or chronic based on endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and X-ray findings. According to their report, we considered our case to be more like the acute calculous cholecystitis complicated by Mirizzi syndrome (type I).

B-ultrasound is the preferred method for the diagnosis of Mirizzi syndrome, the results of which provide a relatively reliable basis for the diagnosis of Mirizzi syndrome. Conversely, CT examinations without enhanced visualization and 3D reconstruction of the bile duct are of little significance for the diagnosis of Mirizzi syndrome. Moreover, ERCP is necessary to improve the accuracy of the preoperative diagnosis. MRCP has an imaging effect close to that of X-ray cholangiography with contrast, which shows not only the biliary system but also the surrounding tissue structures and anatomical patterns when combined with conventional MR cross-sectional imaging. This technique has the advantages of a non-invasive nature, favorable patient compliance, no need for contrast agents, and unique imaging, which allow its application in the diagnosis of Mirizzi syndrome and can elevate the preoperative diagnosis rate of this condition[5].

Mirizzi syndrome is mainly treated with surgeries, among which laparoscopic applications were previously listed as a contraindicated surgery by many surgeons. Laparoscopic surgery has been increasingly reported because of its rapid development in recent years. Moreover, surgeons with experience in complex laparoscopic surgery have a significantly lower rate of conversion to open surgery as compared to general surgeons. Whether open or minimally invasive surgery is used, the treatment of Mirizzi syndrome should conform to the principles of gallbladder removal, stone extraction, obstruction relief, bile duct repair, and adequate drainage. Tay et al[6] conducted a retrospective analysis of 3560 patients undergoing cholecystectomy and found that partial or subtotal cholecystectomy is a safe and feasible option for difficult gallbladders, with low morbidity rates and no common bile duct injury or mortality. Meanwhile, the key to surgery for Mirizzi syndrome is to correct the existing stenosis of the common bile duct, to avoid iatrogenic bile duct injury, not to insist on minimally invasive surgery, and to decisively convert to open surgery if necessary[1]. Intriguingly, similar to advances in endoscopic technology, advances in surgical technology can lessen bile duct damage in patients with Mirizzi syndrome. For instance, Lim et al[7] utilized indocyanine green dye fluorescence cholangiography (ICG-FC) in minimal access cholecystectomy for visualizing the extrahepatic biliary tree, and the results showed that ICG-FC is safe and improves the visualization of the common hepatic duct. Of note, general surgeons are not trained to manage severe complications such as bile duct injury and patients should be referred to hepato-pancreato-biliary surgeons when difficulty arises. Therefore, there is a lack of awareness regarding the need for calling for help prior to open conversion, and this issue should be addressed to improve patient outcomes[8].

ERCP is a technique where a duodenoscope is inserted into the descending portion of the duodenum to locate the duodenal papilla and a contrast catheter is inserted into the biopsy channel to the opening of the papilla to inject contrast agents for radiography, thus showing the pancreaticobiliary duct. ERCP is highly preferred by patients because of no incision, less trauma, shorter surgical time, and fewer complications, obviously shorter hospital stays as compared to surgical procedures. ERCP is an indispensable and important tool for the diagnosis and treatment of biliary stones and can be used as a transitional drainage treatment of Mirizzi syndrome before complex surgery with the advances in technologies such as endoscopic papillary balloon dilation, electrohydraulic lithotripsy, laser lithotripsy under endoscopic choledochoscopy (SpyGlass), and biliary stent placement. Therefore, ERCP not only has the role of confirming the diagnosis of Mirizzi syndrome and also can unblock the bile duct, drain, and abate jaundice to solve practical problems, such as bile duct strictures, when combined with endoscopic naso-biliary drainage and internal stent drainage, thus creating conditions for surgery and repressing postoperative complications[9]. In conclusion, ERCP plays an extremely clear and increasingly critical role in the treatment of Mirizzi syndrome.

SpyGlass is an ultra-fine choledochoscope with a tube diameter of 3.5 mm, which is placed into the bile duct for direct visual exploration with the help of ERCP to find the exact location of the lesion and conduct the relevant surgery. SpyGlass requires only one surgeon to operate and directly visualize all bile ducts, which enables one surgeon to perform definitive diagnosis and treatment in a single surgery. The SpyGlass surgery has been validated to be clinically feasible, which not only can be used for clinical diagnosis but also provides sufficient samples for histological analysis and successfully guides electrohydraulic and laser lithotripsy[10-14]. Electrohydraulic lithotripsy relies on high-pressure shock waves between working electrodes but is not operated under direct vision, thus causing the risk of bile duct injury. On the contrary, the direct vision system of SpyGlass can be utilized for lithotripsy and biopsy under direct vision to improve the diagnosis and treatment[15-17]. SpyGlass is an effective treatment option for a range of biliary tract disorders, including the management of massive bile duct stones, partial cystic duct stones, gallbladder flushing and drainage, partial intrahepatic bile duct stones, common bile duct stones, and suspect occupied lesions of bile ducts. Traditional ERCP needs to be assisted by X-rays and constantly display the operation route through radiography. Conversely, the use of SpyGlass allows the visualization of operations in front of a screen with all visual images of the whole biliary tree. Therefore, SpyGlass-assisted X-ray-free ERCP breaks through the blind spot of the original endoscopic treatment and enables ERCP to enter a new stage.

Several conclusions can be obtained from this case. First, B-ultrasound, abdominal CT, MRCP, and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can all be used for the diagnosis of Mirizzi syndrome but objectively result in a certain rate of misdiagnosis. In addition, MRCP and EUS have a higher sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of Mirizzi syndrome. Second, ERCP can be utilized for the treatment of various pancreaticobiliary duct diseases and is now widely used in clinical practice because it is minimally invasive and integrates diagnosis and treatment. Meanwhile, ERCP can also be used as a transitional drainage treatment before the complex surgery of Mirizzi syndrome. Third, the emergence of SpyGlass is a highlight, breaking through the blind spot of the original endoscopic treatment, because it can be used for biopsy or even lithotripsy in cholangiopancreatic ducts under direct vision. The possible complications of SpyGlass-assisted X-ray-free ERCP, including pancreatitis, bleeding, infection, perforation, and bile duct obstruction or stricture, still require attention. Collectively, laser or electrohydraulic lithotripsy under the direct vision of SpyGlass is safe and effective for the treatment of type I Mirizzi syndrome, which does not increase postoperative complications compared with conventional lithotripsy and lithotomy under ERCP.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shelat VG, Singapore; Shiryajev YN, Russia S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Shiryajev YN, Glebova AV, Koryakina TV, Kokhanenko NY. Acute acalculous cholecystitis complicated by MRCP-confirmed Mirizzi syndrome: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3:193-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Issa H, Bseiso B, Almousa F, Al-Salem AH. Successful Treatment of Mirizzi's Syndrome Using SpyGlass Guided Laser Lithotripsy. Gastroenterology Res. 2012;5:162-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Klekowski J, Piekarska A, Góral M, Kozula M, Chabowski M. The Current Approach to the Diagnosis and Classification of Mirizzi Syndrome. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Morelli A, Narducci F, Ciccone R. Can Mirizzi syndrome be classified into acute and chronic form? An endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) study. Endoscopy. 1978;10:109-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lai W, Yang J, Xu N, Chen JH, Yang C, Yao HH. Surgical strategies for Mirizzi syndrome: A ten-year single center experience. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;14:107-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tay WM, Toh YJ, Shelat VG, Huey CW, Junnarkar SP, Woon W, Low JK. Subtotal cholecystectomy: early and long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:4536-4542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lim SH, Tan HTA, Shelat VG. Comparison of indocyanine green dye fluorescent cholangiography with intra-operative cholangiography in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:1511-1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chan KS, Hwang E, Low JK, Junnarkar SP, Huey CWT, Shelat VG. On-table hepatopancreatobiliary surgical consults for difficult cholecystectomies: A 7-year audit. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2022;21:273-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Clemente G, Tringali A, De Rose AM, Panettieri E, Murazio M, Nuzzo G, Giuliante F. Mirizzi Syndrome: Diagnosis and Management of a Challenging Biliary Disease. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018:6962090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bauzon J, Haller S, Aponte-Pieras JR, Lankarani D, Schreiber A, Houshmand N, Wahid S. Unusual Case of Mirizzi Syndrome Presenting as Painless Jaundice. Am J Case Rep. 2022;23:e936836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nguyen NQ, Shah JN, Binmoeller KF. Diagnostic cholangioscopy with SpyGlass probe through an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography cannula. Endoscopy. 2010;42 Suppl 2:E288-E289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kantsevoy SV, Frolova EA, Thuluvath PJ. Successful removal of the proximally migrated pancreatic winged stent by using the SpyGlass visualization system. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:454-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Baron TH, Saleem A. Intraductal electrohydraulic lithotripsy by using SpyGlass cholangioscopy through a colonoscope in a patient with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:650-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen YK, Pleskow DK. SpyGlass single-operator peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy system for the diagnosis and therapy of bile-duct disorders: a clinical feasibility study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:832-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Laleman W, Verraes K, Van Steenbergen W, Cassiman D, Nevens F, Van der Merwe S, Verslype C. Usefulness of the single-operator cholangioscopy system SpyGlass in biliary disease: a single-center prospective cohort study and aggregated review. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:2223-2232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Colombi D, Aragona G, Bodini FC, Zangrandi A, Morelli N, Michieletti E. SpyGlass percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy-guided diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the ampullary region in a patient with bariatric biliopancreatic diversion. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2019;18:291-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yan S, Tejaswi S. Clinical impact of digital cholangioscopy in management of indeterminate biliary strictures and complex biliary stones: a single-center study. Ther Adv Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;12:2631774519853160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |