Published online Jul 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i21.5014

Peer-review started: March 16, 2023

First decision: June 12, 2023

Revised: June 18, 2023

Accepted: June 27, 2023

Article in press: June 27, 2023

Published online: July 26, 2023

Processing time: 132 Days and 11.2 Hours

Intussusception is a primary cause of intestinal obstruction in young children. Delayed diagnosis is associated with increased morbidity. Ultrasonography (USG) is the gold standard for diagnosis, but it is operator dependent and often unavai

To study the clinical characteristics of intussusception including management and evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of abdominal radiography (AR) and the promising parameters found in the pediatric intussusception score (PIS).

Children with suspected intussusception in our center from 2006 to 2018 were recruited. Clinical manifestations, investigations, and treatment outcomes were recorded. AR images were interpreted by a pediatric radiologist. Diagnosis of intussusception was composed of compatible USG and response with reduction. The diagnostic value of the proposed PIS was evaluated.

Ninety-seven children were diagnosed with intussusception (2.06 ± 2.67 years, 62.9% male), of whom 74% were < 2 years old and 37.1% were referrals. The common manifestations of intussusception were irritability or abdominal pain (86.7%) and vomiting (59.2%). Children aged 6 mo to 2 years, pallor, palpable abdominal mass, and positive AR were the parameters that could discriminate intussusception from other mimics (P < 0.05). Referral case was the only significant parameter for failure to reduce intussusception (P < 0.05). AR to diagnose intussusception had a sensitivity of 59.2%. The proposed PIS, a combination of clinical irritability or abdominal pain, children aged 6 mo to 2 years, and compatible AR, had a sensitivity of 85.7%.

AR alone provides poor screening for intussusception. The proposed PIS in combination with common manifestations and AR data was shown to increase the diagnostic sensitivity, leading to timely clinical management.

Core Tip: Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in young children. Early diagnosis and prompt management can lead to favorable outcomes. Ultrasonography is considered the gold standard for diagnosis, while abdominal radiography is typically used as the initial imaging study in suspicious cases. The present study found that AR had a sensitivity of 59.2%, but the sensitivity increased to 85.7% when in combination with data on clinical irritability, abdominal pain, and age. Pediatric intussusception score might be a helpful tool for general physicians or pediatricians in limited resource settings for early diagnosis and timely referral to increase favorable outcomes.

- Citation: Rukwong P, Wangviwat N, Phewplung T, Sintusek P. Cohort analysis of pediatric intussusception score to diagnose intussusception. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(21): 5014-5022

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i21/5014.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i21.5014

Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in young children under 2 years old. The classic triad of manifestations are abdominal pain, bloody stool, and palpable abdominal mass. These symptoms occur in less than 40% of cases[1,2] with one study reporting symptoms in only 2.9%[3] of cases, making timely diagnosis difficult. Bowel infarction and perforation, leading to peritonitis and death, are the serious complications with delayed or missed diagnosis[3-6]. Abdominal ultrasonography (USG) is the gold standard for investigation[7], but requires an experienced radiologist and timely availability that is often limited in some geographic areas. Abdominal radiography (AR) is more readily available but its value for diagnosing intussusception is low[8,9].

Previous studies have developed a risk stratification model for the diagnosis of intussusception that integrates clinical signs and symptoms with AR[10]. This complicated algorithm has not yet been validated. The present study aimed to study the demographic data, disease characteristics, and condition management of children who had clinically suspected intussusception to identify parameters that are helpful for general physicians to diagnose intussusception. The diagnostic value of AR alone or together with promising parameters to diagnose intussusception and the proposed pediatric intussusception score (PIS) were evaluated.

Medical records of 151 children aged less than 18 years who had clinically suspected intussusception and completed an AR and abdomen USG as part of their work-up as evaluated by pediatric residents at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand from January 2006 to June 2018 were included in the present study. The participants were categorized into intussusception and non-intussusception groups after the final diagnosis. Intussusception was diagnosed by the findings of the abdominal USG (target/pseudo-kidney/doughnut signs and hypoechoic or multiple concentric masses) and clinical improvement after reduction or open surgery for manual reduction. The non-intussusception group was comprised of children that had clinically suspected intussusception, but whose final diagnosis identified other diseases. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chulalongkorn University (IRB number: 515/60).

Patient demographic data, characteristics, clinical manifestations, causes of intussusception, comorbidities, imaging studies including USG and AR, and management were collected from medical records.

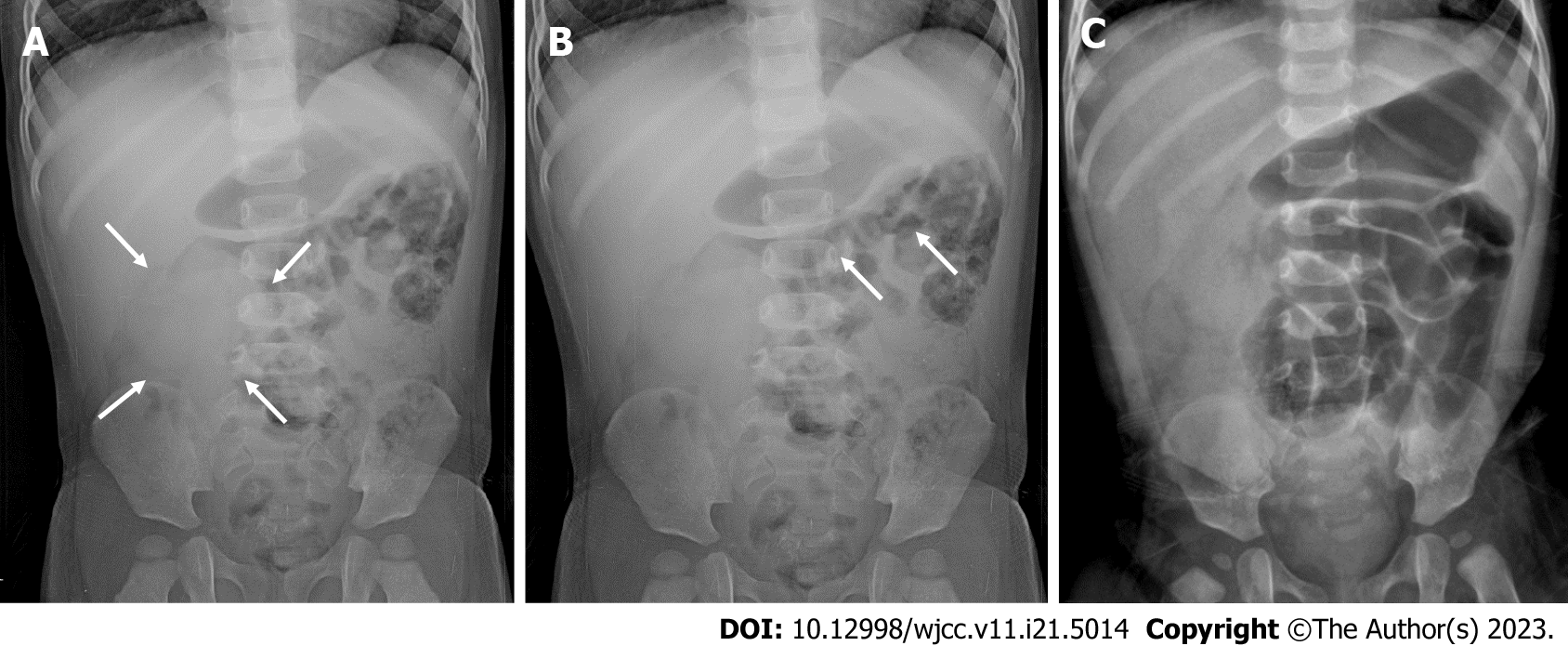

AR images of all participants were blindly interpreted by a pediatric radiologist as a positive or negative finding for intussusception. The positive finding for intussusception was defined as: (1) An abnormal soft tissue mass in the right sided abdomen (Figure 1A); or (2) Small amount of stool or air in the transverse colon (Figure 1B); or (3) Intestinal obstruction (localized bowel dilatation with paucity/absent distal bowel gas (Figure 1C) or multiple air-fluid levels in the same bowel loop on additional upright position).

Continuous and categorical data are presented as the mean ± SD and percentages, respectively. The independent t-test and chi-square analysis were used to assess group differences for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value (NPV), and positive predictive value (PPV) were calculated for AR with and without promising parameters to diagnose intussusception. The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science version 22.0. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

One hundred and fifty-one children with suspected intussusception were enrolled in the study with a mean age of 2.47 ± 3.09 years, and 64.2% of them were male. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. In the non-intussusception group, conditions that could mimic intussusception including acute gastroenteritis, Henoch Schönlein Purpura, constipation, colic, colitis, acute appendicitis, midgut malrotation with volvulus, incarcerated inguinal hernia, and Meckel’s diverticulitis were diagnosed. No difference in gender was observed between the intussusception and non-intussusception groups. Age 6 mo to 2 years old, pallor, abdominal mass, and positive AR were the characteristics that showed statistical differences between intussusception and non-intussusception cases (P < 0.05). Only 11.3% of the children presented with the classical symptom triad for intussusception (abdominal pain, bloody stool, and palpable abdominal mass) with none in the non-intussusception group. The triad had a sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 11.3%, 100%, 100%, and 45.2%, respectively, to diagnose intussusception (data not shown).

| Parameter | Intussusception (n = 97) | Non-intussusception (n = 54) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 2.06 (2.67) | 2.78 (2.92) | 0.121 |

| Age 6 mo to 2 years | 64 (65.3) | 23 (41.8) | 0.005 |

| Male gender | 62 (63.3) | 35 (63.6) | 0.964 |

| Hospital setting | |||

| Emergency department to ward | 61 (62.9) | 43 (79.6) | 0.028 |

| Refer from other hospitals | 36 (37.1) | 11 (20.4) | |

| Season | |||

| Winter | 40 (41.2) | 18 (33.3) | |

| Rainy | 23 (23.71) | 19 (35.1) | 0.493 |

| Summer | 34 (35.05) | 17 (31.5) | |

| Clinical signs and symptoms | |||

| Prodomal infection | 7 (7.1) | 5 (9.1) | 0.668 |

| Fever | 21 (21.4) | 18 (32.7) | 0.126 |

| Pallor | 7 (7.1) | 9 (16.7) | 0.081 |

| Lethargy | 24 (24.5) | 17 (30.9) | 0.391 |

| Irritability or abdominal pain | 85 (86.7) | 44 (80) | 0.275 |

| Non-bilious vomiting | 58 (59.2) | 33 (60) | 0.921 |

| Bilious vomiting | 7 (7.1) | 6 (10.9) | 0.426 |

| Abnormal stool frequency /consistency | 29 (29.9) | 20 (34) | 0.412 |

| Bloody stool | 35 (35.7) | 14 (25.5) | 0.194 |

| Abdominal distension | 39 (39.8) | 20 (36.4) | 0.676 |

| Palpable mass at abdomen | 24 (24.5) | 0 (0) | 0.001 |

| Lethargy | 24 (24.5) | 17 (30.9) | 0.391 |

| Seizure | 5 (5.1) | 1 (1.8) | 0.336 |

Of 97 cases diagnosed with intussusception, all were < 3 years old, 62 (63.3%) were male, and 41.2% of the intussusception cases occurred during winter (December to February). There were no seasonal differences for intussusception occurrence. The sites of intussusception as determined by USG were ileocecum (45.4%), hepatic flexure (16.5%), splenic flexure (5.2%), and small bowel (1%), with 31.9% having no data. Leading points could be identified in 28 cases, including Meckel’s diverticulum (n = 3), Burkitt lymphoma (n = 1), polyp (n = 5), Crohn’s disease (n = 2), appendix (n = 2), hamartomatous polyp (n = 3), Juvenile polyp (n = 1), ileal lymphoid hyperplasia, or mesenteric lymph node (n = 11). In addition, 74 (76.3%) children diagnosed with intussusception had successful reduction of intussusception and 23 (23.7%) had open surgery. There were 12 children in which the first attempt at reduction failed. Successful reduction after the 2nd and 3rd attempts occurred in 7 and 2 children, respectively. The three children who had failed multiple reductions had pathological leading points of hamartomatous polyp (n = 1) and appendix (n = 2). A total of 7 cases had a recurrence of intussusception, of which 4, 2, and 1 children had 2, 3, and 5 episodes of intussusception after reduction, respectively. Three (42.9%) children had pathological leading points of juvenile polyp (n = 1) and hamartomatous polyp (n = 2). Complications that followed the delayed diagnosis and treatment included septicemia (n = 3), coagulopathy (n = 1), blood loss that needed blood transfusion (n = 2), hypovolemic shock (n = 1), and bowel ischemia and perforation (n = 3). Interestingly, 4 patients had seizures within 12 h after pneumatic reduction. Two of these cases had fever.

Twenty-five (25.8%) children diagnosed with intussusception had failed intussusception reduction. Referral cases had a significantly higher rate (38.9%) of failure to reduce intussusception with subsequent open surgery compared to the non-referral group (17.7%) [odds ratio = 2.95, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.16-7.51)]. There was no significant difference in age, gender, clinical manifestations, AR, or sites of intussusception as determined by USG between the referral and non-referral groups (data not shown).

AR images were interpreted blindly by a pediatric radiologist and had a sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV to diagnose intussusception of 59.2%, 70.9%, 78.4%, and 49.4%, respectively.

Promising parameters including common age group, common manifestations (abdominal pain or irritability, vomiting, and abdominal distension), significant manifestations that could discriminate between intussusception and other mimic diseases (pallor and palpable mass), and AR images were chosen and combined to establish models that could help general physicians timely identify suspected intussusception prior to confirmation by abdomen USG. The combination of the user-friendly triad (age 6 mo to 2 years old, abdominal pain or irritability, and AR) that we have termed the “Pediatric Intussusception Score” had a sensitivity of 85.7% (Table 2) and an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.704 (95%CI: 0.616-0.790) (Table 3).

| Promising parameters and proposed models | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy |

| AR | 0.592 | 0.709 | 0.784 | 0.494 | 0.634 |

| Male gender | 0.633 | 0.382 | 0.646 | 0.368 | 0.542 |

| Age 6 mo to 2 years | 0.653 | 0.582 | 0.736 | 0.485 | 0.627 |

| Vomiting | 0.592 | 0.400 | 0.637 | 0.355 | 0.523 |

| Bloody stool | 0.357 | 0.745 | 0.714 | 0.394 | 0.497 |

| Irritability or abdominal pain | 0.867 | 0.200 | 0.659 | 0.458 | 0.627 |

| Abdominal distension | 0.398 | 0.636 | 0.661 | 0.372 | 0.484 |

| Palpable abdominal mass | 0.245 | 1 | 1 | 0.426 | 0.516 |

| Fever | 0.214 | 0.673 | 0.538 | 0.325 | 0.379 |

| Lethargy | 0.245 | 0.691 | 0.585 | 0.339 | 0.405 |

| Age 6 mo to 2 years + irritability or abdominal pain | 0.959 | 0.091 | 0.653 | 0.556 | 0.647 |

| Age 6 mo to 2 years + irritability or abdominal pain + palpable abdominal mass | 0.704 | 0.582 | 0.75 | 0.525 | 0.66 |

| Age 6 mo to 2 years + irritability or abdominal pain + abdominal distension | 0.959 | 0.091 | 0.653 | 0.556 | 0.647 |

| Age 6 mo to 2 years + irritability or abdominal pain + vomiting | 0.959 | 0.091 | 0.653 | 0.556 | 0.647 |

| Model 1: AR + age 6 mo to 2 years + irritability or abdominal pain | 0.857 | 0.455 | 0.737 | 0.641 | 0.712 |

| Model 2: AR + age 6 mo to 2 years + irritability or abdominal pain + palpable abdominal mass | 0.816 | 0.545 | 0.762 | 0.625 | 0.719 |

| Model 3: AR + age 6 mo to 2 years + irritability or abdominal pain + abdominal distension | 0.857 | 0.455 | 0.737 | 0.641 | 0.712 |

| Model 4: AR + age 6 mo to 2 years + irritability or abdominal pain + vomiting | 0.857 | 0.455 | 0.737 | 0.641 | 0.712 |

| Promising parameters and proposed models | AUC | 95%CI | P value | |

| AR | 0.650 | 0.560 | 0.741 | 0.002a |

| Male gender | 0.507 | 0.412 | 0.603 | 0.882 |

| Age 6 mo to 2 years | 0.617 | 0.524 | 0.711 | 0.016a |

| Vomiting | 0.504 | 0.408 | 0.600 | 0.933 |

| Bloody stool | 0.551 | 0.457 | 0.645 | 0.293 |

| Abdominal pain or irritability | 0.534 | 0.437 | 0.630 | 0.490 |

| Abdominal distension | 0.517 | 0.422 | 0.613 | 0.725 |

| Palpable abdominal mass | 0.622 | 0.535 | 0.710 | 0.012a |

| Afebrile state | 0.556 | 0.460 | 0.653 | 0.247 |

| Lethargy | 0.532 | 0.436 | 0.628 | 0.511 |

| Model 1: AR + age 6 mo to 2 years + irritability or abdominal pain | 0.704 | 0.616 | 0.792 | < 0.001a |

| Model 2: AR + age 6 mo to 2 years + irritability or abdominal pain + palpable abdominal mass | 0.763 | 0.688 | 0.839 | < 0.001a |

| Model 3: AR + age 6 mo to 2 years + irritability or abdominal pain + abdominal distension | 0.640 | 0.550 | 0.729 | 0.004a |

| Model 4: AR + age 6 mo to 2 years + irritability or abdominal pain + vomiting | 0.701 | 0.613 | 0.790 | < 0.001a |

The present study described the clinical characteristics, investigations, and management of children with suspected intussusception and assessed the diagnostic accuracy of AR alone and with promising parameters for intussusception. The main result of the study supports using AR with clinical irritability or abdominal pain among children aged 6 mo to 2 years to initially diagnose intussusception with good sensitivity. We are calling this combination of parameters the PIS.

Intussusception is an emergency condition that is common in young children where raised suspicion can lead to early diagnosis and successful treatment with a favorable outcome. Physicians should be aware of the common characteristics of intussusception to manage these patients properly. In previous studies, the common age of presentation was between 6 mo and 2 years old and a male predominance was observed[2,3,11]. The age and gender of children in the present study were comparable to those reported in other previous studies. Most children diagnosed with intussusception were diagnosed in the winter, but the statistics did not reach significance. Winter was not evidenced as a common time of intussusception in this era[12], so seasonal distribution may no longer be a clue for intussusception. In addition, clinical manifestations of intussusception are varied[13] and the well-known triad of abdominal pain or irritability, palpable abdominal mass, and bloody stool was infrequently found[3] in early presentation. Bloody stool[14] and palpable abdominal mass[3] were the parameters for failure in the reduction of intussusception. Predictors of intussusception have been postulated in many studies[7,13,15,16]. Weihmiller et al[10] was the first group who proposed a risk stratification for children being evaluated for intussusception in a prospective observational cohort study. Validation of this stratification has not occurred. Apart from the triad, the common manifestations of intussusception include lethargy, vomiting, irritability or crying, and pallor[10,13,17,18]. In the present study, abdominal pain or irritability and vomiting were the two most common manifestations in children with suspected intussusception but these symptoms were unable to discriminate intussusception from other mimic diseases. However, we could identify significant symptoms including pallor and abdominal mass that were more specific to intussusception. Although abdominal mass was found only in one fourth of cases, no children in the non-intussusception group had a palpable mass. We assumed that it is difficult for general physicians to engage a child and palpate abdominal mass especially in a child with irritability or excessive crying. Consequently, AR could be an investigative tool that could increase the ability to detect the soft tissue opacity in children with intussusception and was therefore included in our model. Pallor tends to be a subjective measure and was found in only 7.1% of cases in the present study. We did not include this parameter in our final screening model.

Since our hospital is a tertiary care center, many referral cases from other provinces were admitted for further ma

Apart from bowel perforation after reduction of intussusception, recurrent intussusception occurred in 13.1% of cases and seizure after reduction in 6.1%. Neurological manifestations of intussusception have been reported in many studies[24-26] such as lethargy, pinpoint pupils, hypotonia, and somnolence, but clinical seizure in children with intussusception was reported in only a few studies[27,28]. A possible explanation for these neurological disturbances in intussusception lies in the mediators or endotoxins that can cross the blood-brain barrier and alter brain metabolism. As the gastrointestinal tract is a reservoir of endotoxins and mucosal integrity is a major component that prevents the impermeability of the toxins, ischemic injury in intussusception might lead to the translocation of the toxins to the circulatory system and also to the brain[29-31]. Another hypothesis is that mediators are released during the ischemic process or after the reperfusion period or successful reduction of intussusception[28]. In the present study, since two in four children had fever during admission, febrile convulsion could not be excluded. However, the two (50%) other children had no fever and seizures occurred after successful reduction of intussusception. Three (75%) of them underwent multiple attempts at intussusception reduction. Consequently, we recommend that children who have successful reduction of intussusception, especially after multiple attempts, should be admitted to the hospital for observation.

Our study has several strengths. We compared children with intussusception to mimics to identify potential parameters for intussusception detection. Furthermore, AR was the initial investigation in all children with suspected intussusception and was interpreted blindly by a pediatric radiologist. One drawback in the present study was that we included both retrospective and prospective cases in the study. Some data were not available such as the exact time of onset and exposure to causative agents such as the rotavirus vaccine and other infections. Another potential limitation was the relatively small number of participants in some subpopulations of interest. A prospective study at multiple sites to evaluate the PIS is needed before the tool can be recommended for wider use.

Early diagnosis and prompt management of intussusception can lead to more favorable outcomes. Unlike abdominal ultrasonography, AR is not the gold standard test to diagnose intussusception because of its low sensitivity. However, AR is user-friendly and operator independent for front-line doctors who are faced with this disease. A combination of AR with clinical parameters of clinical irritability or abdominal pain among children between 6 mo and 2 years that we have called the “Pediatric Intussusception Score (PIS)” can increase the diagnostic accuracy for intussusception. PIS might be a user-friendly tool for general physicians or general pediatricians in limited resource areas to improve the ability to make early diagnosis of intussusception and accelerate patient referral to increase favorable outcomes.

Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in young children. Bowel infarction and perforation, leading to peritonitis and death, are the more serious complications of late or missed diagnoses. Abdominal ultrasonography (USG) is the gold standard of investigation, but these procedures require an experienced radiologist and timely availability of the USG machine that is often limited.

To develop a user-friendly tool that could help front-line doctors diagnose intussusception in resource limited areas to improve clinical case management.

The present study aimed to study the demographic data, disease characteristics, and management of children with suspected intussusception, and to describe the user-friendly parameters that are helpful for general physicians to diagnose intussusception.

Medical records of 151 children, aged less than 18 years, who had clinically suspected intussusception and had completed abdominal radiography (AR) and abdomen USG procedures as part of the work-up during evaluation by pediatric residents at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital from January 2006 to June 2018 were included in the present study. Diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value (NPV), and positive predictive value (PPV) were calculated for AR with and without promising parameters to diagnose intussusception. USG is considered the gold standard to diagnose intussusception.

One hundred and fifty-one children with suspected intussusception were included in the study with a mean age of 2.47 ± 3.09 years, with 64.2% of them were male. Characteristics that could discriminate intussusception from non-intussusception included children aged 6 mo to 2 years old, pallor, abdominal mass, and positive AR (P < 0.05). AR images (n = 133) were interpreted blindly by a pediatric radiologist and had a sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV to diagnose intussusception of 59.2%, 70.9%, 78.4%, and 49.4%, respectively. Promising parameters including common age group, common manifestations (abdominal pain or irritability, vomiting, and abdominal distension), significant manifestations that could discriminate intussusception and other mimic diseases (pallor and palpable mass), and AR images were chosen and combined to establish models that could help general physicians to identify suspected intussusception prior to timely confirmation by abdomen USG. The combination of the user-friendly triad (children aged 6 mo to 2 years old, abdominal pain or irritability, and AR) that we termed the “Pediatric Intussusception Score” showed diagnostic value for intussusception with a sensitivity of 85.7% and an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.704 (95% confidence interval: 0.616-0.790).

AR is considered a poor diagnostic tool for intussusception. It is operator independent and front-line doctors in rural areas can use this tool to identify suspected cases of intussusception. Positive AR could help the doctor to decide which cases to refer to secondary or tertiary hospitals for specific and timely management in time. Two clinical parameters that doctors should be aware with intussusception were integrated into the PIS. The PIS will help young doctors have confidence to make initial diagnoses of intussusception.

Further study to validate the PIS for the diagnosis of intussusception is warranted.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Thailand

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Govindarajan KK, India; Raza HA S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Waseem M, Rosenberg HK. Intussusception. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24:793-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Simon NM, Joseph J, Philip RR, Sukumaran TU, Philip R. Intussusception: Single Center Experience of 10 Years. Indian Pediatr. 2019;56:29-32. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Wong CW, Chan IH, Chung PH, Lan LC, Lam WW, Wong KK, Tam PK. Childhood intussusception: 17-year experience at a tertiary referral centre in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2015;21:518-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Daneman A, Navarro O. Intussusception. Part 1: a review of diagnostic approaches. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33:79-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Daneman A, Navarro O. Intussusception. Part 2: An update on the evolution of management. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:97-108; quiz 187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Navarro O, Daneman A. Intussusception. Part 3: Diagnosis and management of those with an identifiable or predisposing cause and those that reduce spontaneously. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:305-12; quiz 369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Harrington L, Connolly B, Hu X, Wesson DE, Babyn P, Schuh S. Ultrasonographic and clinical predictors of intussusception. J Pediatr. 1998;132:836-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tareen F, Mc Laughlin D, Cianci F, Hoare SM, Sweeney B, Mortell A, Puri P. Abdominal radiography is not necessary in children with intussusception. Pediatr Surg Int. 2016;32:89-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Aronson PL, Henderson AA, Anupindi SA, Servaes S, Markowitz RI, McLoughlin RJ, Woodford AL, Mistry RD. Comparison of clinicians to radiologists in assessment of abdominal radiographs for suspected intussusception. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29:584-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Weihmiller SN, Buonomo C, Bachur R. Risk stratification of children being evaluated for intussusception. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e296-e303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Flaum V, Schneider A, Gomes Ferreira C, Philippe P, Sebastia Sancho C, Lacreuse I, Moog R, Kauffmann I, Koob M, Christmann D, Douzal V, Lefebvre F, Becmeur F. Twenty years' experience for reduction of ileocolic intussusceptions by saline enema under sonography control. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51:179-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jiang J, Jiang B, Parashar U, Nguyen T, Bines J, Patel MM. Childhood intussusception: a literature review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Territo HM, Wrotniak BH, Qiao H, Lillis K. Clinical signs and symptoms associated with intussusception in young children undergoing ultrasound in the emergency room. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:718-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | He N, Zhang S, Ye X, Zhu X, Zhao Z, Sui X. Risk factors associated with failed sonographically guided saline hydrostatic intussusception reduction in children. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:1669-1675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kuppermann N, O'Dea T, Pinckney L, Hoecker C. Predictors of intussusception in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:250-255. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Klein EJ, Kapoor D, Shugerman RP. The diagnosis of intussusception. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2004;43:343-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lochhead A, Jamjoom R, Ratnapalan S. Intussusception in children presenting to the emergency department. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2013;52:1029-1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yap Shiyi E, Ganapathy S. Intussusception in Children Presenting to the Emergency Department: An Asian Perspective. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33:409-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jenke AC, Klaassen-Mielke R, Zilbauer M, Heininger U, Trampisch H, Wirth S. Intussusception: incidence and treatment-insights from the nationwide German surveillance. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:446-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Xiaolong X, Yang W, Qi W, Yiyang Z, Bo X. Risk factors for failure of hydrostatic reduction of intussusception in pediatric patients: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e13826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wylie R. Foreign bodies and bezoars. In: Nelson textbook of pediatrics; 18th edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. 1571. |

| 22. | Henderson AA, Anupindi SA, Servaes S, Markowitz RI, Aronson PL, McLoughlin RJ, Mistry RD. Comparison of 2-view abdominal radiographs with ultrasound in children with suspected intussusception. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29:145-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Roskind CG, Kamdar G, Ruzal-Shapiro CB, Bennett JE, Dayan PS. Accuracy of plain radiographs to exclude the diagnosis of intussusception. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:855-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Meyer JS, Dangman BC, Buonomo C, Berlin JA. Air and liquid contrast agents in the management of intussusception: a controlled, randomized trial. Radiology. 1993;188:507-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Applegate KE. Intussusception in children: evidence-based diagnosis and treatment. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39 Suppl 2:S140-S143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Branski D, Shatsberg G, Gross-Kieselstein E, Hurvitz H, Goldberg M, Abrahamov A. Neurological dysfunction as a presentation of intussusception in an infant. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:604-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ko SF, Lee TY, Ng SH, Wan YL, Chen MC, Tiao MM, Liang CD, Shieh CS, Chuang JH. Small bowel intussusception in symptomatic pediatric patients: experiences with 19 surgically proven cases. World J Surg. 2002;26:438-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kleizen KJ, Hunck A, Wijnen MH, Draaisma JM. Neurological symptoms in children with intussusception. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:1822-1824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Dankoff S, Puligandla P, Beres A, Bhanji F. An unusual presentation of small bowel intussusception. CJEM. 2015;17:318-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Conway EE Jr. Central nervous system findings and intussusception: how are they related? Pediatr Emerg Care. 1993;9:15-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Heldrich FJ. Lethargy as a presenting symptom in patients with intussusception. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1986;25:363-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |