Published online Jul 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i20.4843

Peer-review started: April 3, 2023

First decision: May 31, 2023

Revised: June 8, 2023

Accepted: June 26, 2023

Article in press: June 26, 2023

Published online: July 16, 2023

Processing time: 99 Days and 20.2 Hours

Sudden death is unanticipated, non-violent death taking place within the first 24 h after the onset of symptoms. It is a major public health problem worldwide. Moreover, the effects of living at moderate altitude on mortality are poorly understood.

To retrospectively report the frequency and the main causes of sudden deaths in relation to total deaths at Asir Central Hospital, 2255 m above sea level, in the southern region of Saudi Arabia over a period of 4 years from 2013 to 2016.

The medical records of 1821 deaths were examined and showed 353 cases (19.4%) of sudden death.

The highest incidence of sudden death was among the elderly (51%), whereas, the lowest was among children and adolescents (6.5%). With regard to gender, the incidence of sudden death was higher in males (54.4%) compared to 45.6% in females. In this study, we found that the most common direct causes of sudden death were cardiovascular diseases (29.2%), respiratory disease (22.7%), infectious disease (12.2%), cancer (9.4%) and hematological diseases (6.2%). With respect to seasonal variation, the highest incidence was during winter (31.32%) followed by summer (25.8%).

The results of this study will help emergency physicians and health care providers to exercise due care to reduce the incidence of sudden death and raise public awareness about the impact of sudden death.

Core Tip: The effects of living at moderate altitude on mortality are poorly understood. Moreover, it has been argued that living at moderate altitudes could be more protective against the development of diseases than living at high altitudes. These reported associations on the incidence and mortality of various diseases with different lifestyles at distinct altitude levels still need further investigation. Indeed, wide-scale comparisons between different altitudes as well as sea level will help to address the impact of high altitude on the incidence and mortality of various diseases. The results of this study will help emergency physicians and health care providers to exercise due care to reduce the incidence of sudden death.

- Citation: Al-Emam AMA, Dajam A, Alrajhi M, Alfaifi W, Al-Shraim M, Helaly AM. Sudden death in the southern region of Saudi Arabia: A retrospective study. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(20): 4843-4851

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i20/4843.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i20.4843

Sudden death is a non-violent, unpredicted death occurring within the first day from the onset of symptoms. Sudden death occurs in all age groups: Infants, children and adolescents, adults and the elderly[1,2]. The risk factors of sudden death consist of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, aging, extremes of body mass index, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, unhealthy diet and stress[3,4]. In addition, the incidence of sudden death exhibits substantial seasonal variations with the highest peak in winter, followed by fall, spring and summer[5]. Moreover, the etiology of sudden death varies with age, gender, ethnicity and genetics[1,6,7]. Thus, history of previous syncope, family history of sudden cardiac death, coronary artery disease, abnormal electrocardiogram with prolongation of QTc interval or with the Brugada syndrome features, poor left ventricular function or features of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy should alert the physician to the risk of sudden cardiac death[6].

It is noteworthy that the available data on the effects of high altitude residence on mortality due to various diseases seem to be inconsistent possibly due to differences in behavioral factors, ethnicity, genetics and the complex interactions with environmental conditions. The epidemiological data indicate that living at higher altitudes is associated with lower mortality from cardiovascular and digestive diseases, certain types of cancer and stroke. In contrast, mortality due to respiratory diseases and suicides is somewhat elevated[8-10]. Moreover, the correct diagnosis in cases of sudden death is always a challenging task to achieve without postmortem examination. In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, postmortem is ordered only in cases of suspicious death, such as violence. Routine autopsies are not carried out for religious and cultural reasons, thus establishing the etiology of sudden death is difficult. Inappropriately, there is little research on the frequency, manner and etiology of sudden death in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Only scarce data on sudden death are available in the literature. For instance, one study from the medicolegal center in Dammam reported unexplained sudden death syndrome in 51 cases[11]. Another study was from a university hospital in the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia[12]. Thus, this study aimed at evaluating the incidence and the main underlying causes of sudden death at Asir Central Hospital, 2255 m above sea level, in the southern region of Saudi Arabia over a period of four years from 2013 to 2016.

The medical records of 1821 deaths that occurred at Asir Central Hospital over a period of four years between January, 2013 and December 2016 were retrospectively evaluated. Death was categorized as sudden death when the patient died unexpectedly from non-violent causes within 24 h from the onset of symptoms of their ante-mortem clinical presentation. The others were classified as expected death.

In all cases of sudden death, the following data were collected from the medical records: Personal information including age, sex, nationality, race and marital status, history of pre-existing diseases, main complaint(s) on pre

This work has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of College of Medicine at King Khalid University, Abha, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, (REC #2016-05-01). Moreover, this study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee.

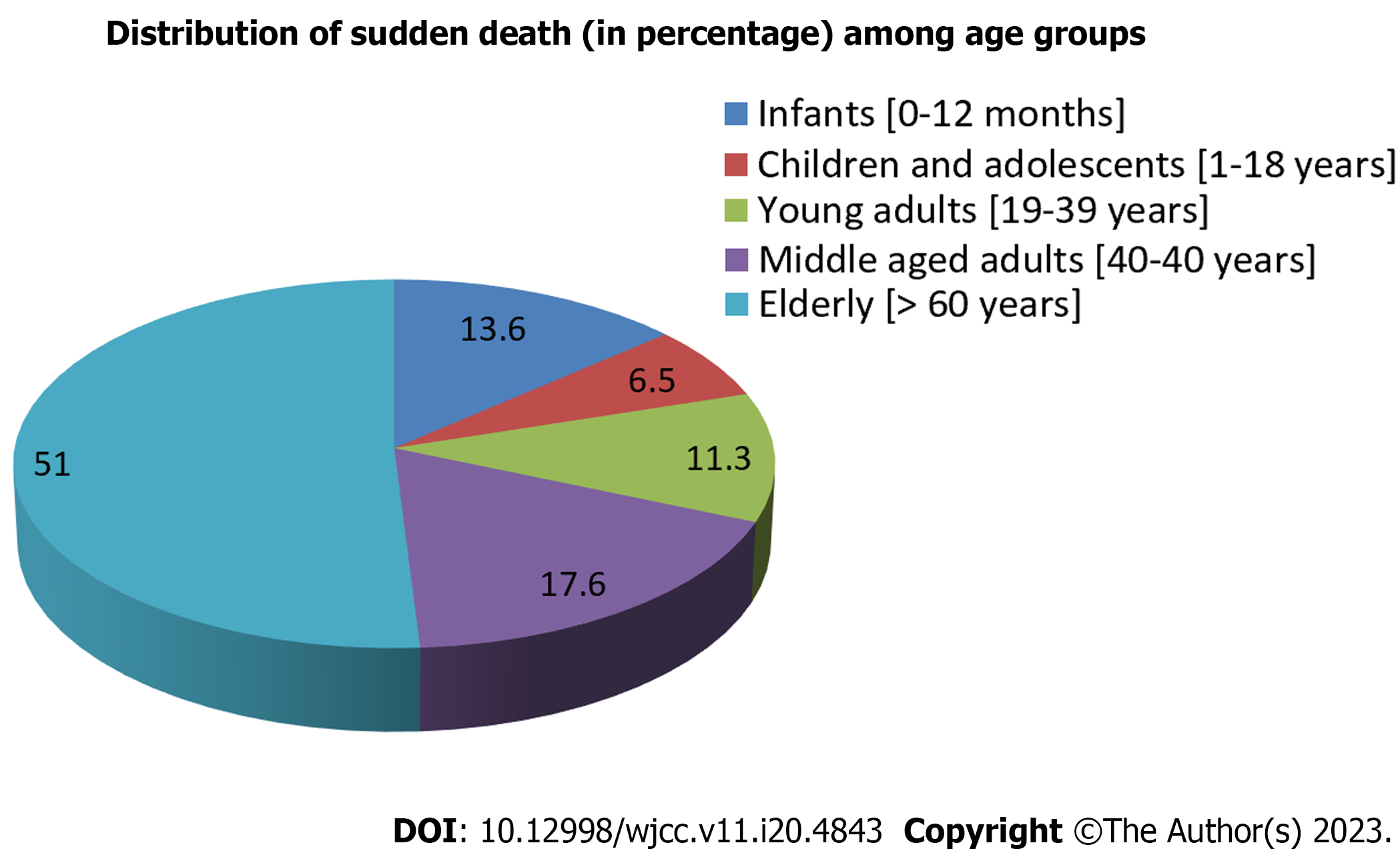

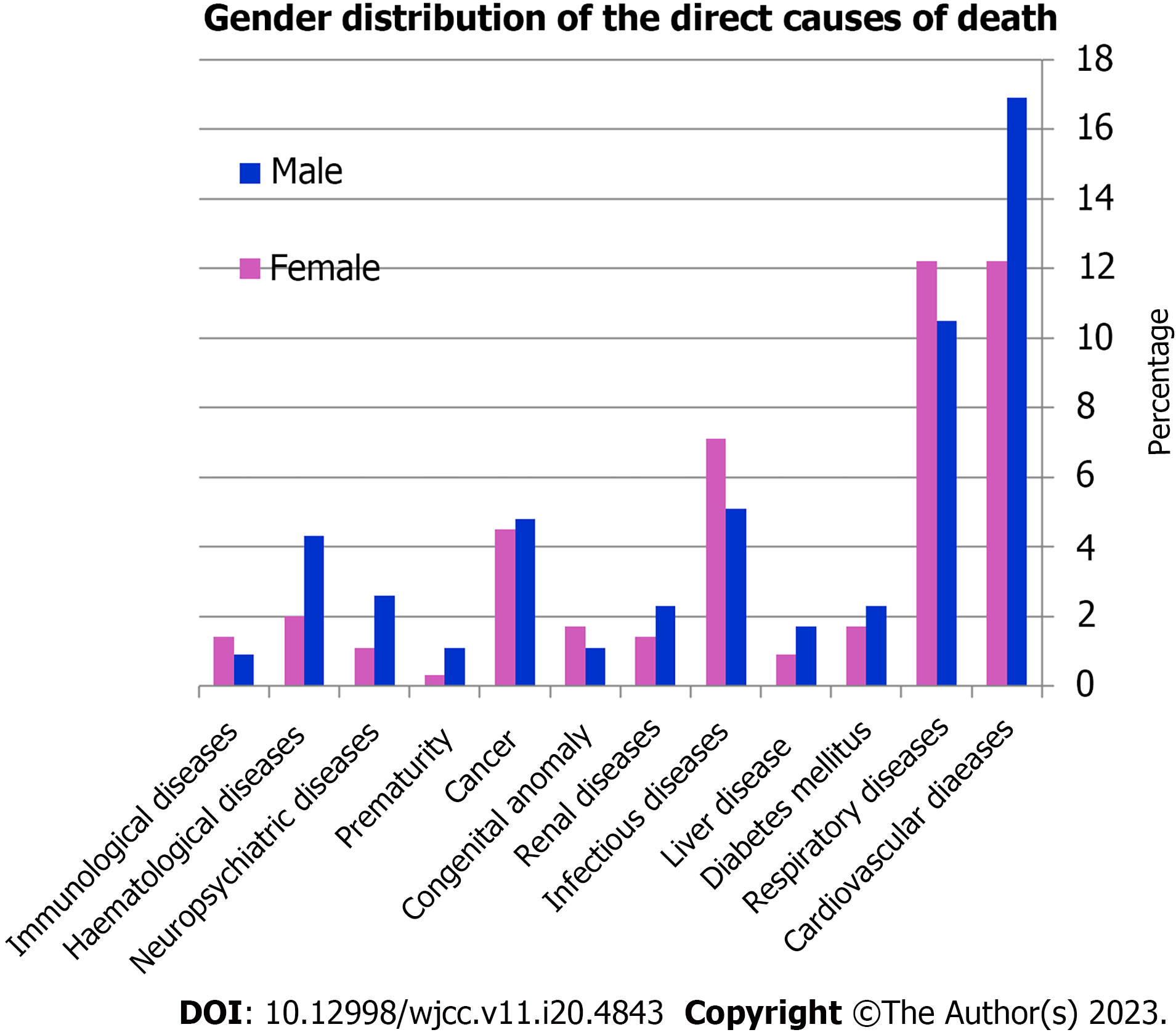

The data analysis revealed 353 cases (19.4%) of sudden death out of the studied 1821. The remaining 80.6% were categorized as expected death. The majority of the patients who died suddenly were Saudi (92.2%, n = 329) whereas, non-Saudi represented 6.8% (n = 24). With regard to the distribution of sudden deaths among different age groups (shown in Figure 1); the peak incidence was among the elderly (51%, n = 180), whereas, it was 17.6% (n = 62), 13.6% (n = 48) and 11.3% (n = 40) among middle-aged adults, infants and young adults, respectively. Only 6.5% (n = 23) of the studied sudden death cases were children and adolescents. With regard to gender, as shown in Figure 2, the incidence of sudden death was higher in males (54.4%, n = 192) compared to 45.6% in females (n = 161). In this study, we found that the most common direct causes of sudden death in relation to gender, as shown in Figure 2 and Table 1, were cardiovascular diseases [29.2%: 60 males (16.9%) and 43 females (12.2%)], respiratory disease [22.7%: 37 males (10.5%) and 43 females (12.2%)], infectious disease [12.2%: 18 males (5.1%) and 25 females (7.1%)], cancer [9.4%: 17 males (4.8%) and 16 females (4.5%)], hematological diseases [6.2%: 15 males (4.3%) and 7 females (2%)], including glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, and sickle cell disease. The other causes were diabetes mellitus [4%: 8 males (2.3%) and 6 females (1.7%)], liver disease [2.6%: 6 males (1.7%) and 3 females (0.9%)], renal disease [3.7%: 8 males (2.3%) and 5 females (1.4%)], congenital anomaly [2.8%: 4 males (1.1%) and 6 females (1.7%)], prematurity [1.4%: 4 males (1.1%) and 1 female (0.3%], neuropsychiatric diseases [3.7%: 9 males (2.6%) and 4 females (1.1%)] and immunological diseases [2.3%: 3 males (0.9%) and 5 females (1.4%)], including rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. It is noteworthy that the cardiovascular causes consisted of coronary artery diseases [21.8%: 50 males (14.2%) and 27 females (7.7%)], hypertension [2.8%: 7 males (2%) and 3 females (0.3%)], stroke [2%: 5 males (1.4%) and 2 females (0.6%)], cardiogenic shock [0.9%: 2 males (0.6%) and 1 female (0.3%)] and life-threatening arrhythmias [1.7%: 4 males (1.1%) and 2 females (0.6%)]. Also, the respiratory causes consisted of pneumonia [10.8%: 17 males (4.8%) and 21 females (6%)], respiratory failure [1.1%: 1 male (0.3%) and 3 females (0.9%)], asthma [2.7%: 3 males (0.9%) and 5 females (1.4%)] and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [8.5%: 11 males (3.1%) and 18 females (5.4%)].

| Direct causes of death | Gender | Total | ||||

| Male | Female | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| CVS | 60 | 16.9 | 43 | 12.2 | 103 | 29.2 |

| CAD1 including MI2 | 50 | 14.2 | 27 | 7.7 | 77 | 21.8 |

| Hypertension | 7 | 2 | 3 | 0.9 | 10 | 2.8 |

| Stroke | 5 | 1.4 | 2 | 0.6 | 7 | 2 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 2 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.9 |

| Life threatening arrhythmias | 4 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.6 | 6 | 1.7 |

| Respiratory disease | 37 | 10.5 | 43 | 12.2 | 80 | 22.7 |

| Pneumonia | 17 | 4.8 | 21 | 6 | 38 | 10.8 |

| Respiratory failure | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.9 | 4 | 1.1 |

| Asthma | 3 | 0.9 | 5 | 1.4 | 8 | 2.7 |

| COPD | 11 | 3.1 | 19 | 5.4 | 30 | 8.5 |

| Infectious disease | 18 | 5.1 | 25 | 7.1 | 43 | 12.2 |

| Cancer | 17 | 4.8 | 16 | 4.5 | 33 | 9.4 |

| Hematological disease | 15 | 4.3 | 7 | 2 | 22 | 6.2 |

| Neuropsychiatric disease | 9 | 2.6 | 4 | 1.1 | 13 | 3.7 |

| Renal disease | 8 | 2.3 | 5 | 1.4 | 13 | 3.7 |

| DM | 8 | 2.3 | 6 | 1.7 | 14 | 4 |

| Liver disease | 6 | 1.7 | 3 | 0.9 | 9 | 2.6 |

| Congenital anomaly | 4 | 1.1 | 6 | 1.7 | 10 | 2.8 |

| Prematurity | 4 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.3 | 5 | 1.4 |

| Immunological disorders | 3 | 0.9 | 5 | 1.4 | 8 | 2.3 |

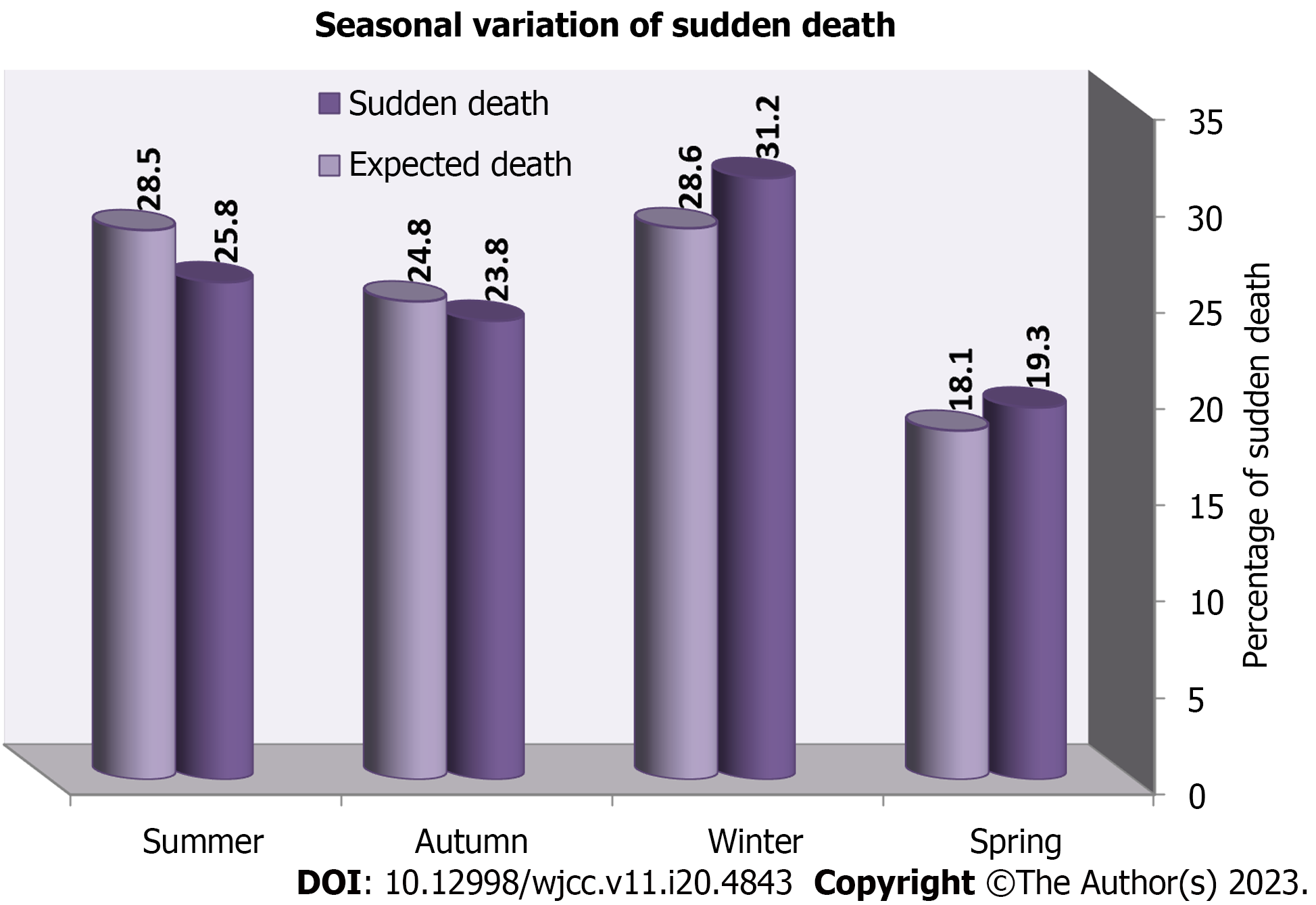

With respect to seasonal variation, the highest incidence of sudden death was seen in winter (January-March) (31.32%: n = 110) and the lowest was during spring (April-June) (19.3%: n = 68), whereas, it was 25.8% (n = 91) and 23.8% (n = 84) during summer (July-September) and autumn (October-December), respectively (Figure 3). It should be noted that the highest incidence of expected death was almost equal during summer and winter months [28.5% (n = 418) and 28.6% (n = 420), respectively). However, the lowest incidence of expected death was during spring [18.1% (n = 266)], whereas, it was 24.8% (n = 264) during autumn (Figure 3).

With regard to the presenting symptoms, as shown in Table 2, chest pain, dyspnea, fever and disturbed consciousness were the most common presenting symptoms with frequencies of 26.6% (n = 94), 18.4% (n = 65), 14.7% (n = 52) and 11.1% (n = 39), respectively. Circulatory collapse occurred in 7.7% (n = 27), whereas, both cough and abdominal distension were equally represented with 5.4% (n = 19) each. Also, nausea and vomiting occurred in 3.4% (n = 12), whereas, hemoptysis and hematemesis were almost equally represented with 1.9% (n = 7) for the former and 2.3% (n = 7) for the latter. In addition, seizures and prematurity were the least presenting symptoms with frequencies of 1.7% (n = 4) for the former and 0.7% (n = 5) for the latter. Lastly, the initial presenting symptoms were not reported in 5 cases (1.4%).

| Percentage | No. of cases | Prodromal symptoms |

| 26.6 | 94 | Chest pain |

| 18.4 | 65 | Dyspnea |

| 14.7 | 52 | Fever |

| 11.1 | 39 | Disturbed consciousness |

| 7.7 | 27 | Circulatory collapse |

| 5.4 | 19 | Cough |

| 5.4 | 19 | Abdominal distension |

| 3.4 | 12 | Nausea and vomiting |

| 2.3 | 8 | Hematemesis |

| 1.9 | 7 | Hemoptysis |

| 1.4 | 5 | Not stated |

| 1.1 | 4 | Seizures |

| 0.7 | 2 | Prematurity |

In relation to past medical history (Table 3), cardiovascular, respiratory, infectious, kidney diseases and cancer were the most commonly encountered clinical problems with frequencies of 23.2% (n = 82), 18.8% (n = 66), 15% (n = 53), 8.2% (n = 29) and 7.7% (n = 27), respectively. In addition, hematological disease and diabetes mellitus were almost equally represented with 4.5% (n = 16) for the former and 4.3% (n = 15) for the latter. Moreover, both intestinal and liver diseases were equally represented with 4% (n = 14) each. Also, both neuropsychiatric and congenital diseases were equally represented with 3.4% (n = 12) each. Furthermore, immunological diseases were the least reported in terms of past history with frequencies of 2.8% (n = 10). Lastly, there were no reported clinical data regarding past medical history in 5 cases (0.9%).

| Percentage | No. of cases | Past medical history |

| 23.2 | 82 | Cardiovascular disease |

| 18.8 | 66 | Respiratory disease |

| 15 | 53 | Infectious disease |

| 8.2 | 29 | Kidney disease |

| 7.7 | 27 | Cancer |

| 4.5 | 16 | Hematological disease |

| 4.3 | 15 | Diabetes mellitus |

| 4 | 14 | Intestinal disease |

| 4 | 14 | Liver disease |

| 3.4 | 12 | Neuropsychiatric disease |

| 3.4 | 12 | Congenital disease |

| 2.8 | 10 | Immunological disease |

| 0.9 | 3 | Not stated |

Sudden unexpected death is a public health problem of paramount importance worldwide and Saudi Arabia is not an exception. In the present study, we reported that sudden unexpected death occurred in 19.4% of the total deaths at Asir Central Hospital in the southern region of Saudi Arabia between 2013 and 2016. The data presented in the current study were slightly higher than those in another retrospective study conducted at King Fahd University Hospital[12], Al Khobar, in the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia, which reported that the frequency of sudden unexpected death was 17.5% between 2000 and 2005. These differences could plausibly be attributed to high altitude hypoxia in Asir region; however, this is a research question that requires an in-depth investigation. In contrast to our data, a previous study reported a sudden death incidence of 41% in Canada[13]. Moreover, another study in the United States showed that sudden cardiac death accounted for 61% of all deaths[14]. Furthermore, another investigation of State-wise sudden cardiac death in the United States reported that 63.4% of all cardiac deaths were sudden in terms of onset[15].

In the current study, the frequency of sudden unexpected death was higher in males (54.4%: 192 cases) compared to females (45.6%: 161 cases) and this is consistent with the data reported at King Fahd University Hospital in the eastern region of Saudi Arabia, 56.0% males and 42.2% females[12] and this is in agreement with international experience[3,6,14-18]. However, the incidence of sudden unexpected death among Saudi patients was higher in our study (92.2%) compared to 74.4% of Saudis at King Fahd University Hospital in the eastern region of Saudi Arabia[14]. On the contrary, sudden unexpected death was higher among non-Saudi (25.6%) in the Eastern region[12] compared to 6.8% in the current study. A plausible explanation for such differences could be weather variations between the two regions.

In the present study, sudden death was calculated in all age groups with the highest percentage for the elderly (51%), followed by middle-aged adults (17.6%), infants (13.6%) and young adults (11.3%). However, the lowest percentage was children and adolescents (6.5%). This distribution pattern of sudden death in terms of age is in line with data from other countries[3,19-21]. With regard to seasonal variation, the highest incidence of sudden death was seen in winter (January-March) (31.32%: n = 110) and was 23.8% (n = 84) in autumn (October-December). This is in partial agreement with the results of Katz et al[5] in the Israeli Negev region who found the peak was in winter (31%) and fall (25%). However, in a different study the highest frequency of sudden death was reported in spring (29.6%), followed by summer (25.1%), then fall and winter (22.8% each)[12]. Again these variations might be explained based on the weather pattern in each region.

In line with previous studies, the most common past medical history was cardiovascular diseases including coronary artery disease, hypertension and stroke 23.2% (n = 82)[3,12,14,15,17,18,21-24]. However, with regard to the presenting symptoms, in our study, chest pain, dyspnea, fever and disturbed consciousness were the most common presenting symptoms with frequencies of 26.6% (n = 94), 18.4% (n = 65), 14.7% (n = 52) and 11.1% (n = 39), respectively. These findings were to some extent different to the findings of another study where the most frequent initial presentations were dyspnea, fever and prematurity followed by circulatory collapse, angina and cough[12]. Moreover, previous studies found that syncope was the main presentation in cases of sudden death[25]. These discrepancies may be related to the different variables in the studied population. However, chest pain, dyspnea and fever represent the cardinal symptoms of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, which were the two most common reasons for sudden death reported in our study.

The data presented in our study also indicated that the single most significant direct cause of sudden death was cardiovascular diseases (29.2%), which is in agreement with previously reported findings[3,4,6,12,17,18,20,22,23]. In addition, the next most frequent causes were respiratory disease, infectious disease, cancer and hematological diseases, among others.

It has been previously demonstrated that residence at high altitude diminishes the incidence of several types of cancer and related mortality[26-29]. Although environmental variation could be considered one of the plausible explanations of regional differences in terms of the incidence and mortality rates of various diseases, careful consideration of all possible confounders, such as ethnicity, genetics, urbanization, industrialization, sociocultural and socioeconomic status and adaptation to environmental stressors as well as lifestyle behaviors, is extremely difficult. Moreover, it has been argued that living at moderate altitudes could be more protective against the development of diseases than high altitudes. These reported correlations on the incidence and mortality of various diseases with diverse lifestyles at different altitude levels still need further verification by future studies. It is noteworthy that one of the limitations of this study is the lack of real data regarding the causes of death in other hospitals in Saudi Arabia at sea level. Such data from various altitudes would have made this study more productive and it is our hope that we can conduct wide-scale comparisons between different altitudes as well as sea level as this will help address the impact of high altitude on the incidence and mortality of various diseases.

This aim of this study was to evaluate the incidence and the main underlying causes of sudden death at Asir Central Hospital, 2255 m above sea level, in the southern region of Saudi Arabia over a period of four years from 2013 to 2016. We found that the frequency of sudden death was highest among the elderly and middle-aged adults followed by infants and was highest in winter and autumn. The most important presenting symptoms prior to death were chest pain, dyspnea and fever. Hence, it is highly recommended that health care staff, in particular emergency physicians, exercise due care while managing patients presenting with these initial symptoms, particularly elderly patients, middle-aged adults and infants.

Sudden death is unanticipated, non-violent death taking place within the first 24 h after the onset of symptoms. It is a major public health problem worldwide. Moreover, the effects of living at moderate altitude on mortality are poorly understood.

The effects of living at moderate altitude on mortality are poorly understood. Moreover, it has been argued that living at moderate altitudes could be more protective against the development of diseases than living at high altitudes. These reported correlations on the incidence and mortality of various diseases with diverse lifestyles at different altitude levels still need further investigation.

To report the frequency and etiology of sudden death at Asir Central Hospital, 2255 m above sea level, in the southern region of Saudi Arabia over a period of 4 years from 2013 to 2016.

The medical records of 1821 deaths that occurred at Asir Central Hospital over a period of four years between January, 2013 and December, 2016 were retrospectively evaluated. Death was classified into sudden and expected categories. Death was considered sudden when the patient died unexpectedly within 24 h from the onset of their ante-mortem clinical presentation. The others were classified as expected death.

The frequency of sudden death was highest among the elderly and middle-aged adults followed by infants and was highest in winter and autumn. The most important presenting symptoms prior to death were chest pain, dyspnea and fever.

It is highly recommended that health care staff, in particular emergency physicians, exercise due care while managing patients presenting with these initial symptoms, particularly elderly patients, middle-aged adults and infants.

Wide-scale comparisons between different altitudes as well as sea level will help address the impact of high altitude on the incidence and mortality of various diseases.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Saudi Arabia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dabla PK, India; Ghannam WM, Egypt S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Eckart RE, Scoville SL, Campbell CL, Shry EA, Stajduhar KC, Potter RN, Pearse LA, Virmani R. Sudden death in young adults: a 25-year review of autopsies in military recruits. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:829-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 620] [Cited by in RCA: 595] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Quigley F, Greene M, O'Connor D, Kelly F. A survey of the causes of sudden cardiac death in the under 35-year-age group. Ir Med J. 2005;98:232-235. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Chahine R. [Cardiovascular risk factors: smoking in the context of recent events in Lebanon]. Sante. 1998;8:109-112. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Farley TM, Meirik O, Chang CL, Poulter NR. Combined oral contraceptives, smoking, and cardiovascular risk. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:775-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Katz A, Biron A, Ovsyshcher E, Porath A. Seasonal variation in sudden death in the Negev desert region of Israel. Isr Med Assoc J. 2000;2:17-21. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Sung RJ, Kuo CT, Wu SN, Lai WT, Luqman N, Chan NY. Sudden Cardiac Death Syndrome: Age, Gender, Ethnicity, and Genetics. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2008;24:65-74. |

| 7. | de Vreede-Swagemakers JJ, Gorgels AP, Dubois-Arbouw WI, van Ree JW, Daemen MJ, Houben LG, Wellens HJ. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the 1990's: a population-based study in the Maastricht area on incidence, characteristics and survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1500-1505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 576] [Cited by in RCA: 537] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Burtscher M. Effects of living at higher altitudes on mortality: a narrative review. Aging Dis. 2014;5:274-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Burtscher J, Millet GP, Burtscher M. Does living at moderate altitudes in Austria affect mortality rates of various causes? An ecological study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e048520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Burtscher J, Millet GP, Renner-Sattler K, Klimont J, Hackl M, Burtscher M. Moderate Altitude Residence Reduces Male Colorectal and Female Breast Cancer Mortality More Than Incidence: Therapeutic Implications? Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Elfawal MA. Sudden unexplained death syndrome. Med Sci Law. 2000;40:45-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nofal HK, Abdulmohsen MF, Khamis AH. Incidence and causes of sudden death in a university hospital in eastern Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17:665-670. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Krahn AD, Connolly SJ, Roberts RS, Gent M; ATMA Investigators. Diminishing proportional risk of sudden death with advancing age: implications for prevention of sudden death. Am Heart J. 2004;147:837-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Goraya TY, Jacobsen SJ, Kottke TE, Frye RL, Weston SA, Roger VL. Coronary heart disease death and sudden cardiac death: a 20-year population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:763-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Murai T, Baba M, Ro A, Murai N, Matsuo Y, Takada A, Saito K. Sudden death due to cardiovascular disorders: a review of the studies on the medico-legal cases in Tokyo. Keio J Med. 2001;50:175-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hecht A, Löffler D. [Acute natural death in adults with special reference to the under-50 age group]. Zentralbl Allg Pathol. 1984;129:127-135. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kawakubo K, Lee JS. [Incidence rate of sudden death in Japan]. Nihon Rinsho. 2005;63:1127-1134. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Schatzkin A, Cupples LA, Heeren T, Morelock S, Kannel WB. Sudden death in the Framingham Heart Study. Differences in incidence and risk factors by sex and coronary disease status. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;120:888-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tamakoshi K, Toyoshima H, Yatsuya H. [Gender difference of sudden death]. Nihon Rinsho. 2005;63:1284-1288. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Amital H, Glikson M, Burstein M, Afek A, Sinnreich R, Weiss Y, Israeli V. Clinical characteristics of unexpected death among young enlisted military personnel: results of a three-decade retrospective surveillance. Chest. 2004;126:528-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Loire R, Tabib A. [Unexpected sudden cardiac death. An evaluation of 1000 autopsies]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1996;89:13-18. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Scheffold T, Binner P, Erdmann J, Schunkert H; Mitglieder des Teilprojekts 5 im Kompetenznetz Herzinsuffizienz. [Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy]. Herz. 2005;30:550-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Aktas EO, Govsa F, Kocak A, Boydak B, Yavuz IC. Variations in the papillary muscles of normal tricuspid valve and their clinical relevance in medicolegal autopsies. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1176-1185. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Kocak A, Govsa F, Aktas EO, Boydak B, Yavuz IC. Structure of the human tricuspid valve leaflets and its chordae tendineae in unexpected death. A forensic autopsy study of 400 cases. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1051-1059. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kramer MR, Drori Y, Lev B. Sudden death in young soldiers. High incidence of syncope prior to death. Chest. 1988;93:345-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Najafi E, Khanjani N, Ghotbi MR, Masinaei Nejad ME. The association of gastrointestinal cancers (esophagus, stomach, and colon) with solar ultraviolet radiation in Iran-an ecological study. Environ Monit Assess. 2019;191:152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kious BM, Bakian A, Zhao J, Mickey B, Guille C, Renshaw P, Sen S. Altitude and risk of depression and anxiety: findings from the intern health study. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2019;31:637-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sabic H, Kious B, Boxer D, Fitzgerald C, Riley C, Scholl L, McGlade E, Yurgelun-Todd D, Renshaw PF, Kondo DG. Effect of Altitude on Veteran Suicide Rates. High Alt Med Biol. 2019;20:171-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Brenner B, Cheng D, Clark S, Camargo CA Jr. Positive association between altitude and suicide in 2584 U.S. counties. High Alt Med Biol. 2011;12:31-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |