Published online Jan 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i2.449

Peer-review started: October 14, 2022

First decision: November 22, 2022

Revised: December 4, 2022

Accepted: December 21, 2022

Article in press: December 21, 2022

Published online: January 16, 2023

Processing time: 89 Days and 19.8 Hours

Habitual khat (Catha edulis) chewing has been proven to cause numerous oral tissue changes. However, oral melanoacanthoma triggered by chronic khat chewing is rare. Oral melanoacanthoma is an uncommon, sudden, asymptomatic, benign pigmentation of the oral cavity. Under the microscope, the epithelial layer of the oral mucosa showed dendritic melanocyte proliferation and acanthosis. The study aimed to highlight chronic khat chewing as a trigger for oral melanoacanthoma.

In the current study, we report a case of a 26-year-old male patient with a rare presentation of oral melanoacanthoma triggered by regular khat chewing. Many intrinsic and extrinsic factors can cause oral pigmentation. Chewing khat is an extrinsic factor that can cause several diseases, including oral pigmentation. In this case, the definitive diagnosis was oral melanoacanthoma. This diagnosis was made based on the patient’s history, clinical lesion presentation, and microscopic biopsy results.

Habitual khat (Catha edulis) chewing causes many oral tissue changes including oral melanoacanthoma. The study aimed to highlight chronic khat chewing as a trigger for oral melanoacanthoma.

Core Tip: Habitual khat chewing causes many oral tissue changes including oral melanoacanthoma. Oral melanoacanthoma is a rare and benign oral pigmentation rarely triggered by khat chewing. The patient in the current case with a khat chewing habit presented with unilateral, diffused, and dark pigmentation in the oral mucosa.

- Citation: Albagieh H, Aloyouny A, Alshagroud R, Alwakeel A, Alkait S, Almufarji F, Almutairi G, Alkhalaf R. Habitual khat chewing and oral melanoacanthoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(2): 449-455

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i2/449.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i2.449

Habitual khat (Catha edulis) is commonly found in a few parts of Africa and many countries in the Middle East, such as the Arabian Peninsula. In some cultures, it has been associated with social customs. Recently, with global migration, khat chewing habits have reached the United States, Europe, and Australia[1,2]. Khat chewing is customarily practiced at prolonged social gatherings called khat sessions, lasting several hours each day. The custom usually entails inserting and chewing fresh khat leaves to form a bolus that is held in the lower buccal vestibule against the check on one side or, in rare cases, on both sides. At the end of the session, the quid is expelled, while the juice is partially expectorated and absorbed[3,4].

Fresh khat leaves have psychoactive, sympathomimetic, and euphoric effects caused by a principal alkaloid known as cathinone, which is structurally similar to amphetamine. Khat users chew fresh or dried leaves and buds[5,6]. Many studies have shown that chewing fresh khat leaves causes mood swings, depression, insomnia, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, anorexia, and constipation. Khat is not associated with addiction, but may lead to psychosomatic dependence[7].

Chewing khat causes several potentially harmful systemic health effects, including renal toxicity, gastrointestinal and liver problems, and cardiovascular abnormalities. In addition, long-term khat consumption has been linked to several oral and dental conditions, including keratotic white lesions, mucosal pigmentation, plasma cell stomatitis, teeth attrition and loss, discoloration, temporomandibular joint issues, gingival recession, and periodontal infections[8]. In animals, khat increases the free radicals that cause tissue damage. Thus, high doses of the active ingredient of khat are released into the oral fluids and most of it is absorbed into the oral tissues[9].

Oral melanoacanthoma is an uncommon, sudden, asymptomatic, benign pigmentation of the oral cavity. It typically occurs suddenly and is clinically characterized by diffused, rapidly growing, dark brown to black colored, and macular tissue pigmentation. It commonly affects the buccal mucosa (51.4%), the palate and lips (15%-22%), and the gingiva (> 6%)[10]. African Americas and younger patients are more likely to develop oral melanoacanthoma[11]. Histopathological analysis has revealed dendritic melanocyte dispersion and acanthosis of the superficial epithelium[12]. Oral melanoacanthoma is self-limiting in nature and is secondary to tissue trauma, which stimulates melanocytic activity. It disappears after eliminating irritants or biopsy. This strengthens the reactive nature of the lesions[13].

The Clinical differential diagnosis of oral pigmentation includes several topical and systemic causes. This study aimed to highlight chronic khat chewing as a trigger for oral melanoacanthoma. A review of the literature revealed a few cases of oral melanoacanthoma caused by chewing khat (Catha edulis). This case report describes a rare, unilateral case of oral melanoacanthoma caused by khat chewing in a 26-year-old male patient: “The work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria”[14].

A 26-year-old healthy male Saudi individual with a khat chewing habit of approximately 100 g of khat/2 sessions daily for more than 12 years visited the oral medicine clinic at Dental Hospital, King Saud University, for the examination of oral brown pigmentations.

The patient had a 4-mo history of asymptomatic, unilateral diffuse brown oral pigmentation that appeared abruptly and diffused rapidly. He had discontinued chewing khat upon noticing the oral discoloration. Oral pigmentation was not associated with weight loss, fatigue, or night sweats in this study. The patient reported that he had undergone routine dental follow-up. The patient had no history of drinking soft drinks, chewing tobacco or shisha, smoking, consuming betel nuts, or heavy metal exposure.

The patient was unaware of any medical condition and was not consuming any medications.

He was unaware of any hereditary conditions.

Physical and systemic examination: Physical examination revealed no remarkable skin rash, ascites, jaundice, or any other abnormal findings. The patient had a slightly elevated blood pressure of 122/79 mmHg, a height of 167 cm, and a weight of 75 kg.

Extraoral examination: Extraoral examination revealed no significant findings.

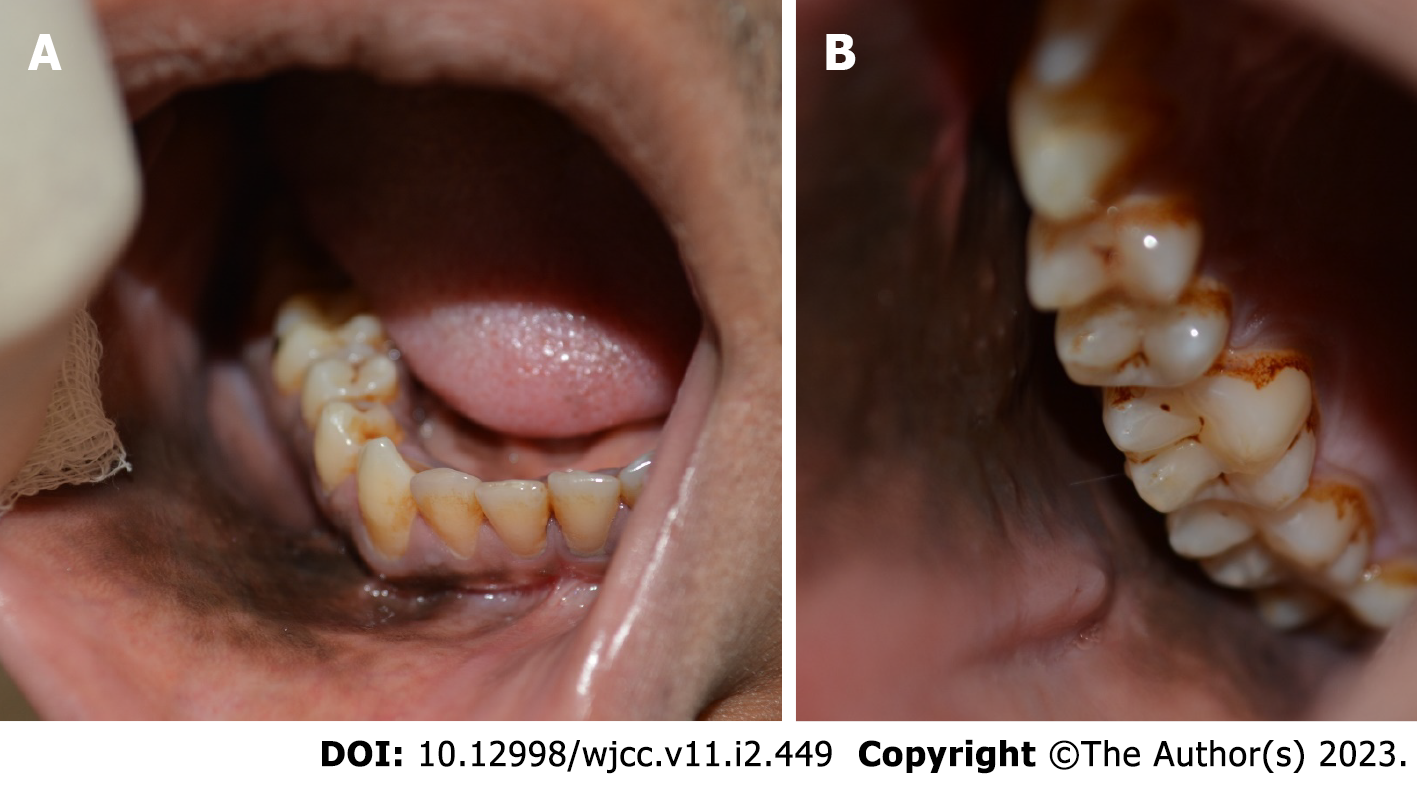

Intraoral examination: On intraoral examination, the patient had full dentition and no clinical dental caries; however, he had poor oral hygiene, tooth discoloration, and a yellowish tongue. The right buccal mucosa, right upper and lower vestibules, soft palate, right upper and lower gingiva, and floor of the mouth were all found to have unilateral, asymptomatic, smooth, macular brownish-black pigmentation with ill-defined margins (Figure 1A and B). The oral cavity showed no signs of leukoplakia, stomatitis, xerostomia, periodontal disease, or keratotic white lesions.

The blood results were within normal limit; a white blood cell count of 9.7 × 103 / mL; a red blood cell count of 5.1 × 106 /mL; a platelet count of 319 × 103 / mL; a hemoglobin count of 14.2 g/dL; cortisol 21 mcg/dL; adrenocorticotropic hormone, 9.1 pmol/L; a blood urea nitrogen value of 24 mg/dL; serum creatinine value of 0.97 mg/dL; potassium, 4.6 mmol/L; sodium, 137 mmol/L; albumin, 49 g/L; total bilirubin of 18 µmol/L; alanine aminotransferase, 48 IU/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 52 IU/L; and alkaline phosphatase, 294 IU/L.

The differential diagnoses of this case included oral melanoacanthoma, physiologic pigmentation, medication-induced pigmentation, Addison’s disease, and melanoma.

After discussing the possible diagnosis with the patient, an incisional biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. The potential risks of surgical and postsurgical consequences, such as infection, delayed wound healing, bleeding, swelling, pain, discomfort, and scarring, were discussed in detail. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient. After administering 1.8 mL of anesthetic solution (lidocaine HCl 2% and epinephrine 1:100000) intraorally via an injection to the buccal mucosa, three soft tissue specimens (5 mm each) were obtained from the darkest areas of the lesion. Theincisions were sutured using Vicryl sutures. Verbal and written instructions were also provided.

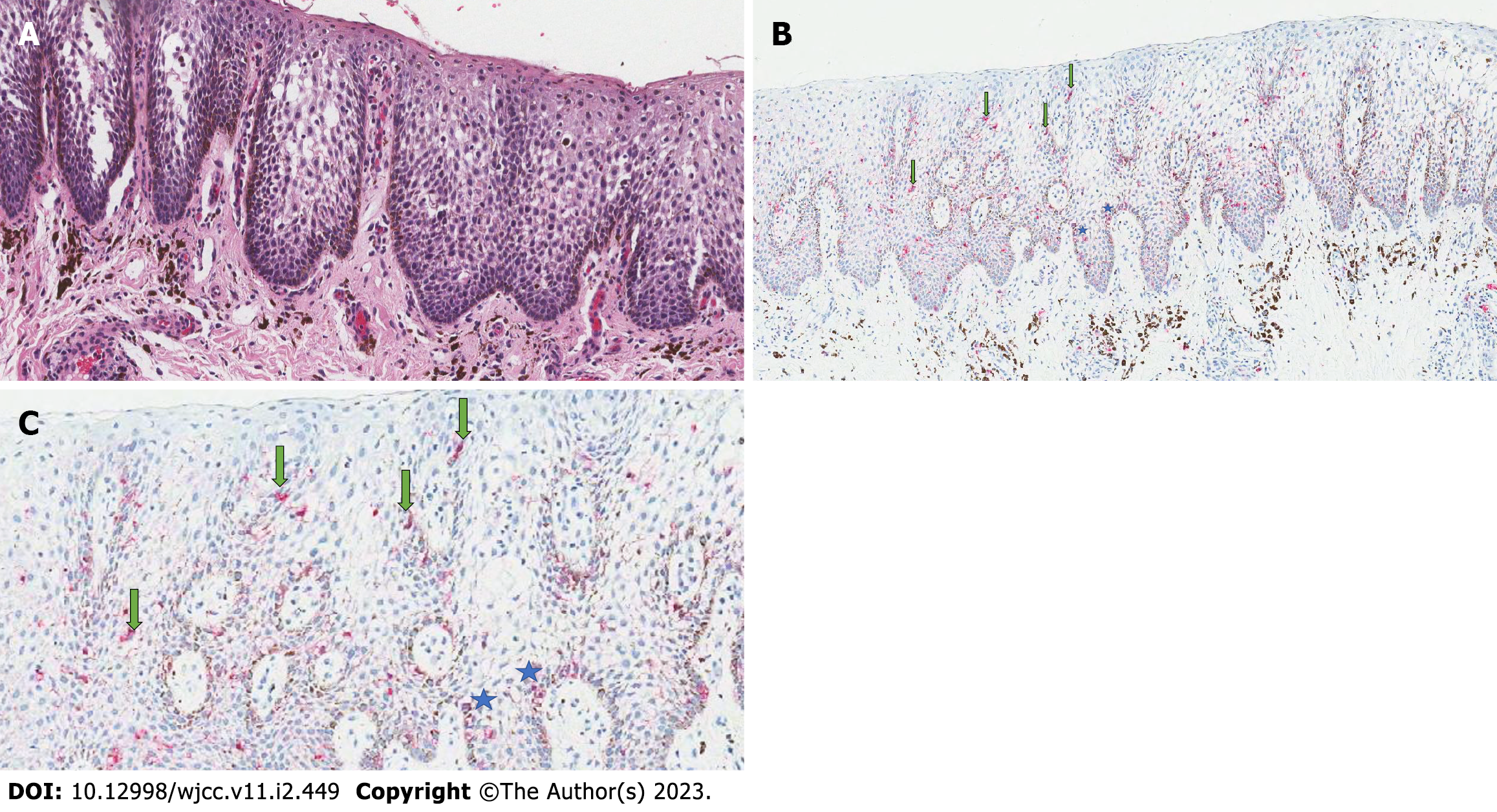

Three gross specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and then sent as three pieces in separate cassettes for histopathological analysis. Histopathological examination of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections revealed acanthosis, spongiosis, and parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium with mild chronic inflammation in the lamina propria of the connective tissue. Multiple dendritic melanocytes were observed in the epithelium (Figure 2A). Additionally, Melan-A-stained tissue sections revealed melanocytic hyperplasia throughout the epithelium with no features of malignancy (Figure 2B and C).

Based on the patient’s history, clinical lesion presentation, and microscopic biopsy result, the definitive diagnosis was oral melanoacanthoma.

The patient was reassured regarding the benign nature of the lesion and was advised to quit chewing khat. Although thelesions appear unpleasant, the pigmentation is harmless and self-limiting and generally disappears without medical intervention.

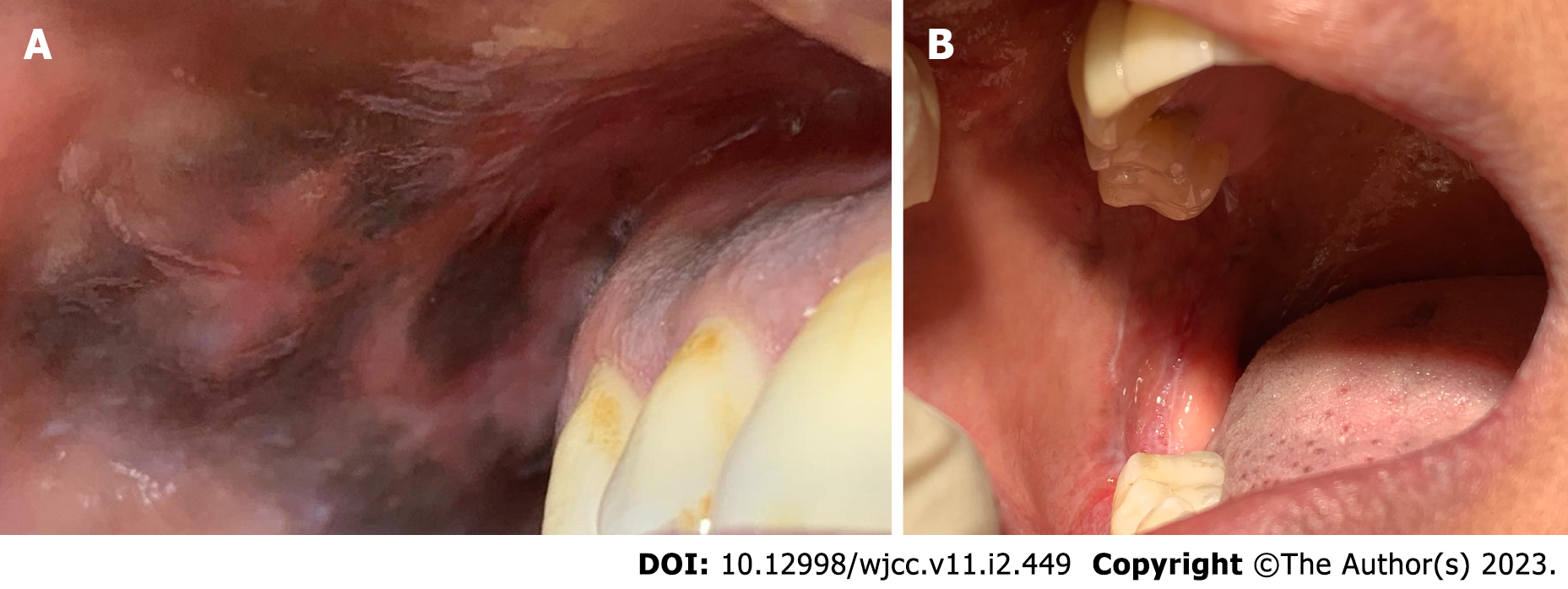

During the 2-mo follow-up visit, the pigmentation disappeared partially (Figure 3A). During the 4-mo follow-up visit, the lesions disappeared completely (Figure 3B). Consequently, the patient discontinued chewing khat owing to the possibility of developing malignant lesions.

Khat chewing may cause mechanical and chemical irritation to the oral tissues. As a result, khat induces oral tissue changes, such as tooth discoloration, dental caries, white and red lesions, mucosal hyperpigmentation, periodontal diseases, and mouth dryness. In animals, khat hampers the body’s ability to clear free radicals. Consequently, free radicals can cause tissue damage. Chronic khat chewers generally keep the khat bolus in the oral vestibule for hours. Therefore, high doses of the active ingredient of khat, “alkaloid cathinone,” are released into the oral fluids and most of it is absorbed into the oral tissues[9]. Melanin production increases in areas of irritation that cause pigmented lesions. Melanin protects against environmental stressors such as ultraviolet radiation and reactive oxygen species. The purpose of increased melanocyte proliferation and production of melanin in the epithelium is to protect and produce a balanced microenvironment that contributes to tissue homeostasis[15].

In this case report, the patient had been a chronic khat chewer for more than 12 years. Hence, for a long time, the khat bolus was in direct contact with the oral soft tissues. After eliminating all other possible causative factors, it was believed that the mechanical and chemical irritation to the oral tissues caused by khat triggered the oral melanoacanthoma in the current case. Oral melanoacanthoma is a rare, asymptomatic, reactive-pigmented lesion that was first documented in 1927 by Bloch[16]. It is described as an ill-defined, flat, or slightly elevated macule, which is diffused, solitary, or multifocal, and dark brown to black in color. It is generally asymptomatic and measures > 1 cm in diameter within a few weeks[17]. Moreover, oral melanoacanthomas possess no potential for malignant transformation. Melanoacanthoma etiopathogenesis is not precisely understood; however, in general, the clinical presentation of pigmentation is suggestive of a reactive lesion caused by mechanical irritation[18].

Clinically, the differential diagnosis includes chewing khat, medication-induced pigmentation, physiological pigmentation, amalgam tattoos, graphite implantation, hygiene products, Addison’s disease, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, McCune-Albright syndrome, post-inflammatory lichen planus, oral melanotic macules, acquired melanotic nevus, metal poisoning, and melanoma. Most of these entities can be ruled out with a precise history, as oral melanoacanthoma can grow suddenly and rapidly in size in a matter of weeks. Moreover, oral melanoacanthoma has an excellent prognosis. Notably, pigmented lesions, in most reported cases, faded gradually following minor trauma or after cessation of the causative agents[19].

Histologically, H&E-stained tissues illustrate hyperplastic and parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium with long rete ridges and acanthosis. Melanin deposits can be observed in the lamina propria. In addition, many benign dendritic melanocytes have dendritic processes throughout the epithelium[20]. Additional melanocytic markers, such as Melan-A or MART-1, tyrosinase, and HMB-45, can be used to confirm the diagnosis of pigmented lesions[21].

The present clinical case has several advantages. A thorough medical and dental history was recorded, a complete clinical examination was performed, and multiple incisional soft tissue biopsies were obtained from the three darkest spots of the pigmented macule. Histopathological examination confirmed oral melanoacanthoma. The patient agreed to quit chewing khat, and the lesion disappeared gradually 4 mo after the oral biopsy.

In general, knowing the etiology of the problem through effective medical history-taking would save time and assist in proper diagnosis. This study aimed to highlight chronic khat chewing as a trigger for oral melanoacanthoma. Further studies are needed to understand the exact effects of chronic khat chewing on oral melanoacanthoma.

The resolution of the pigmented lesion had a positive impact on the patient’s life, as he discontinued chewing khat owing to the possibility of developing malignant lesions. Moreover, the patient regained confidence after the pigmented lesion disappeared.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Dentistry, oral surgery and medicine

Country/Territory of origin: Saudi Arabia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Orlien S, Norway; Zheng KW, China S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Kassim S, Jawad M, Croucher R, Akl EA. The Epidemiology of Tobacco Use among Khat Users: A Systematic Review. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:313692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | J Awadalla N, A Suwaydi H. Prevalence, determinants and impacts of khat chewing among professional drivers in Southwestern Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2017;23:189-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Al-Sharabi AK, Shuga-Aldin H, Ghandour I, Al-Hebshi NN. Qat chewing as an independent risk factor for periodontitis: a cross-sectional study. Int J Dent. 2013;2013:317640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Al-Maweri SA, Alaizari NA, Al-Sufyani GA. Oral mucosal lesions and their association with tobacco use and qat chewing among Yemeni dental patients. J Clin Exp Dent. 2014;6:e460-e466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Al-Hebshi NN, Skaug N. Khat (Catha edulis)-an updated review. Addict Biol. 2005;10:299-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hijazi M, Jentsch H, Al-Sanabani J, Tawfik M, Remmerbach TW. Clinical and cytological study of the oral mucosa of smoking and non-smoking qat chewers in Yemen. Clin Oral Investig. 2016;20:771-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ageely HM. Health and socio-economic hazards associated with khat consumption. J Family Community Med. 2008;15:3-11. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Al-Maweri SA, Warnakulasuriya S, Samran A. Khat (Catha edulis) and its oral health effects: An updated review. J Investig Clin Dent. 2018;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Al-Kholani AI. Influence of Khat Chewing on Periodontal Tissues and Oral Hygiene Status among Yemenis. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2010;7:1-6. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Galindo-Moreno P, Padial-Molina M, Gómez-Morales M, Aneiros-Fernández J, Mesa F, O'Valle F. Multifocal oral melanoacanthoma and melanotic macula in a patient after dental implant surgery. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:817-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tapia JL, Quezada D, Gaitan L, Hernandez JC, Paez C, Aguirre A. Gingival melanoacanthoma: case report and discussion of its clinical relevance. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:253-258. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Cantudo-Sanagustín E, Gutiérrez-Corrales A, Vigo-Martínez M, Serrera-Figallo MÁ, Torres-Lagares D, Gutiérrez-Pérez JL. Pathogenesis and clinicohistopathological caractheristics of melanoacanthoma: A systematic review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2016;8:e327-e336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gondak RO, da Silva-Jorge R, Jorge J, Lopes MA, Vargas PA. Oral pigmented lesions: Clinicopathologic features and review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17:e919-e924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Agha RA, Borrelli MR, Farwana R, Koshy K, Fowler AJ, Orgill DP, et al The SCARE 2018 statement: Updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int J Surg. 2018;60:132-6.. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2076] [Cited by in RCA: 2070] [Article Influence: 295.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Feller L, Masilana A, Khammissa RA, Altini M, Jadwat Y, Lemmer J. Melanin: the biophysiology of oral melanocytes and physiological oral pigmentation. Head Face Med. 2014;10:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bloch B. On benign, non-naevoid melanoepitheliomas of the skin together with comments on the nature and genesis of dendritic cells. Arch f Dermat. 1927;153:20-40. |

| 17. | Brooks JK, Sindler AJ, Scheper MA. Oral melanoacanthoma in an adolescent. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:384-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tomich CE, Zunt SL. Melanoacanthosis (melanoacanthoma) of the oral mucosa. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990;16:231-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CW BJ. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 3rd Edition. 2008. 540 p.. |

| 20. | Fornatora ML, Reich RF, Haber S, Solomon F, Freedman PD. Oral melanoacanthoma: a report of 10 cases, review of the literature, and immunohistochemical analysis for HMB-45 reactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:12-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Carlos-Bregni R, Contreras E, Netto AC, Mosqueda-Taylor A, Vargas PA, Jorge J, León JE, de Almeida OP. Oral melanoacanthoma and oral melanotic macule: a report of 8 cases, review of the literature, and immunohistochemical analysis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12:E374-E379. [PubMed] |