Published online Jan 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i2.434

Peer-review started: October 13, 2022

First decision: November 25, 2022

Revised: December 8, 2022

Accepted: December 18, 2022

Article in press: December 18, 2022

Published online: January 16, 2023

Processing time: 91 Days and 5.7 Hours

Most of the first symptoms of avian influenza are respiratory symptoms, and cases with occipital neuralgia as the first manifestation are rarely reported.

A middle-aged patient complaining of paroxysmal pain behind the ear was admitted to our hospital. The patient’s condition changed rapidly, and high fever, unexpected respiratory failure, and multiple organ failure developed rapidly. The patient was diagnosed with H7N9 avian influenza based on etiology.

We believe that the etiology of occipital neuralgia is complex and could be the earliest manifestation of severe diseases. The possibility of an infectious disease should be considered when occipital neuralgia is accompanied by fever. Avian influenza is one of these causative agents.

Core Tip: Patients with avian influenza usually first show respiratory symptoms, and occipital neuralgia caused by avian influenza is very rare. We report a case of severe avian influenza pneumonia with occipital neuralgia as the first symptom.

- Citation: Zhang J. H7N9 avian influenza with first manifestation of occipital neuralgia: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(2): 434-440

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i2/434.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i2.434

Most of the first symptoms of avian influenza are respiratory symptoms, and cases with occipital neuralgia as the first manifestation are rarely reported. In June 2017, a middle-aged patient complaining of paroxysmal pain behind the ear was admitted to our hospital. The patient’s condition changed rapidly, and high fever, unexpected respiratory failure, and multiple organ failure appeared rapidly. The patient was diagnosed with H7N9 avian influenza by etiology. This case is described as follows.

A 57-year-old male presented with sudden right postauricular tingling for 3 d (onset June 10th).

A 57-year-old male presented with sudden right postauricular tingling for 3 d (onset June 10th). The patient experienced discharge-like pain in the right postauricular region for a few minutes each time, lasting several seconds at a time. The pain was intense and severely affected the patient’s life. No obvious nausea, vomiting, cough, diarrhea, limb weakness, or fever was observed.

There was no special history of past illness.

No special personal and family history.

Physical examination results were normal. Nervous system examination showed that the right postauricular occipital nerve distribution area had acupuncture-induced hypersensitivity, whereas the rest of the nervous system examination showed no abnormalities.

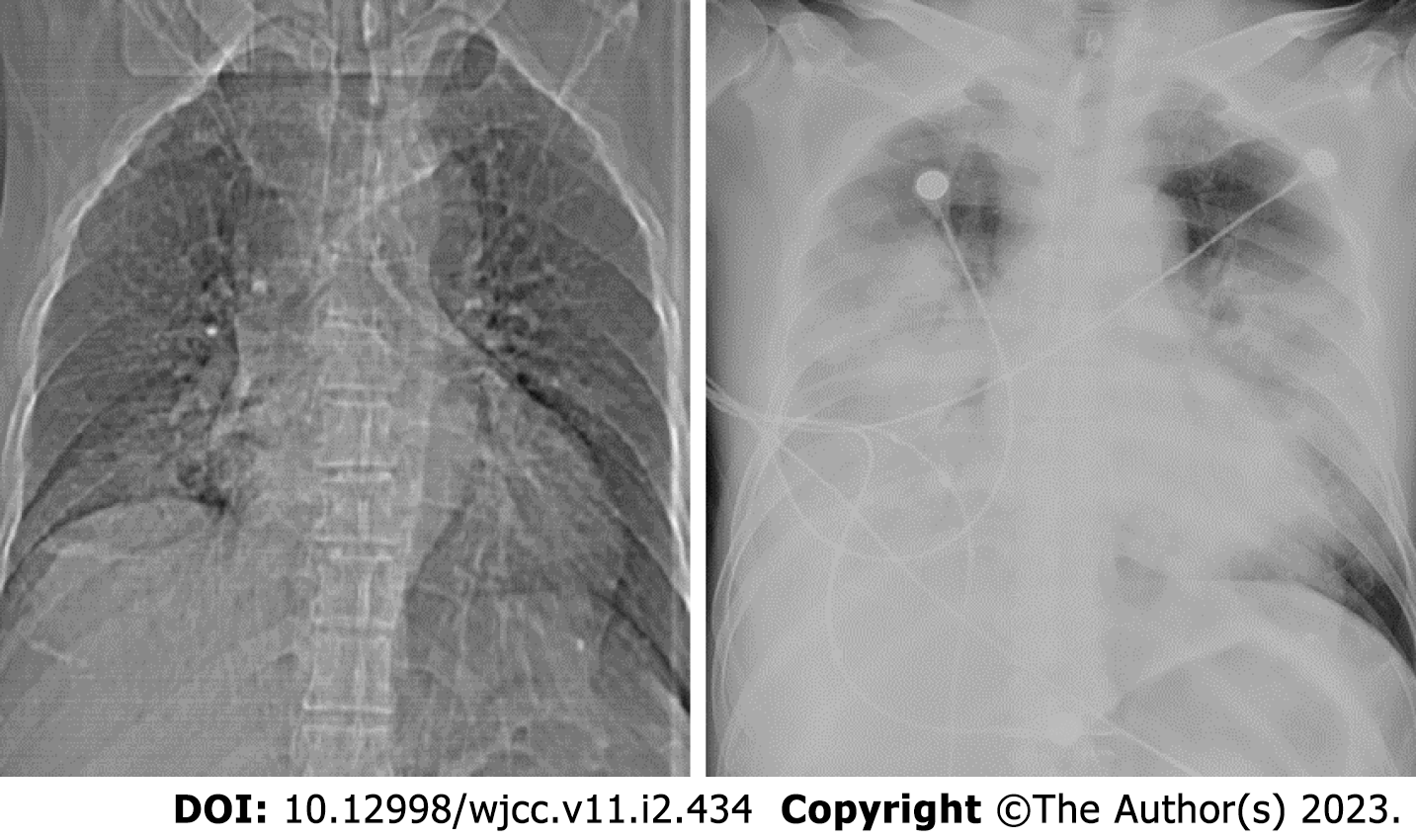

Routine blood analysis showed (June 13th) that the percentage of neutrophils was 84.6%, and the other blood biochemical indicators were generally normal: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), 25 mm/h, sodium: 131.0 mmol/L. Coagulation tests, thyroid function tests (FT3, FT4, TSH, TG-Ab, and TPO-Ab), and liver and kidney function tests were normal. Antistreptolysin O (ASO), rapid detection of infectious diseases, and urine analysis showed no abnormalities. Stool analysis, glycosylated hemoglobin, and serum homocysteine levels were normal. The current perception threshold (CPT) indicated that the right lesser occipital nerve was hypersensitive (with small fibers involved, Table 1). See Tables 2-4 for Biochemical parameters of blood results, blood coagulation function results and Aterial blood gases results of patient. The patient had two chest X-ray examinations, the results were shown in Figure 1. The nucleic acid polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for influenza H7N9 virus in sputum specimens was positive at Chaoyang Hospital on the same day. The specimens sent to the Beijing Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Chinese National Influenza Center (CNIC) tested positive for H7N9 virus.

| Nerve | Left/Right | 2000 Hz (40/244/118) | 250 Hz (4/52/19) | 5 Hz (1/38/10) |

| Lesser occipital nerve | L | 210 | 32 | 30 |

| R | 200 | 60 | 80 | |

| Greater occipital nerve | L | 220 | 52 | 30 |

| R | 220 | 50 | 36 | |

| Greater auricular nerve | L | 160 | 48 | 30 |

| R | 150 | 45 | 26 |

| Time | Routine blood test | Liver function | Renal function | Blood electrolytes | Cardiac function | ||||||||||||||

| WBC (109/L) | NEUT (%) | RBC (1012/L) | HGB (g/L) | PLT (109/L) | ALT (U/L) | AST (U/L) | LDH (U/L) | GGT (U/L) | AMY (U/L) | CK (U/L) | CREA (umol/L) | UREA (mmol/L) | K (mmol/L) | Na (mmol/L) | CL (mmol/L) | BNP (pg/mL) | TNI (pg/mL) | CK-MB (ng/mL) | |

| 6.13 | 6.2 | 87.8 | 4.84 | 149 | 165 | 67 | 4.12 | 3.74 | 139 | 99.1 | |||||||||

| 6.14 | 4.8 | 84.6 | 4.62 | 144 | 144 | 25.2 | 38.2 | 332.8 | 155.6 | 34.1 | 237.4 | 62.6 | 3.83 | 4.03 | 131 | 94.7 | 9.2 | ||

| 6.15AM | 4.1 | 76.1 | 5.17 | 159 | 119 | 220 | 4392 | 10254 | 62 | 5.75 | 4.46 | 123 | 93.2 | 1028 | 70.65 | 15.22 | |||

| 6.15PM | 10.1 | 82.8 | 5.66 | 175 | 138 | 89.7 | 543 | 4926 | 161 | 440 | 11209 | 153 | 9.46 | 4.65 | 116 | 95.6 | 117 | ||

| Time | PT (S) | PT (%) | INR | APTT (S) | FIB (mg/dL) | TT (S) |

| 6.14 | 12.9 | 82.4 | 1.12 | 39.7 | 607.5 | 16.5 |

| 6.15 | 16 | 50.4 | 1.39 | 67.8 | 344.6 | 20.9 |

| Time | PH | PO2 (mmHg) | PCO2 (mmHg) | Lac (mmol/L) | SO2 (%) | BE (mmol/L) | cHCO3 (mmol/L) | A-aDO2 (mmHg) | %FiO2 (L) |

| 6.15 11:25 am | 7.32 | 36 | 37 | 2.1 | 56 | -5.9 | 19.1 | 210 | 41 |

| 6.15 13:37pm | 7.08 | 60 | 55 | 4.9 | 69 | -14 | 16.5 | 584 | 100 |

| 6.15 15:21pm | 7.18 | 56 | 50 | 3 | 75 | -9.8 | 16.5 | 595 | 100 |

Head magnetic resonance imaging is normal. Fever occurred in the afternoon of the same day after admission. The patient had a temperature of 39.2 °C and cough that night. Pulmonary computed tomography (CT) (June 14th) showed inflammation in the right lower lung, fine moist rales in the right lower lung, and normal oxygen saturation. The patient’s condition changed rapidly, and high fever, unexpected respiratory failure, and multiple organ failure. Chest X-ray re-examination showed that bilateral lung infection was significantly worse than yesterday’s chest film (Figure 1).

The patient was finally diagnosed with H7N9 avian influenza by etiology.

Fever occurred in the afternoon of the same day after admission. The patient had a temperature of 39.2 °C and cough that night. Routine blood analysis showed (June 13th) that the percentage of neutrophils was 84.6%, and the other blood biochemical indicators were generally normal: ESR, 25 mm/h, sodium: 131.0 mmol/L. Coagulation tests, thyroid function tests (FT3, FT4, TSH, TG-Ab, and TPO-Ab), and liver and kidney function tests were normal. ASO, rapid detection of infectious diseases, and urine analysis showed no abnormalities. Stool analysis, glycosylated hemoglobin, and serum homocysteine levels were normal. The CPT indicated that the right lesser occipital nerve was hypersensitive (with small fibers involved, Form 1). The patient’s headache was relieved after 0.3 g oxcarbazepine. The patient still had persistent moderate to high fever, cough and sputum, pharyngeal pain, and yellow phlegm with blood filaments. Pulmonary CT (June 14th) showed inflammation in the right lower lung, fine moist rales in the right lower lung, and normal oxygen saturation. An intravenous drip of ceftazidime and levofloxacin was administered to the patient. The consultant of the Respiratory Department considered pneumonia and allowed him to be transferred to the department for further treatment (12:00 am on June 15th). On the day of transfer to the Respiratory Department, the patient experienced bad wheezing and dyspnea. Electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring indicated that oxygenation decreased to 50% (oxygen flow, 10 L/min). Examination revealed widely flooded bubbles in both lungs. The patient had a body temperature of 39.5 °C. Cyanosis of the lip and spots on the trunk and lower extremities were also visible. The patient was administered lysine aspirin (0.45 mg), static push, and noninvasive ventilator-assisted ventilation treatment with the following parameters: S mode, IPAP 14 cm H2O, and EPAP 4 cm H2O. Oxygenation increased to 80%, and dyspnea did not improve. The respiratory frequency was 40 breaths/min, and the ventilator parameters were adjusted to ST mode, IPAP 16 cmH2O, and EPAP 5.0 cm H2O. The patient was given “imipenem combined with moxifloxacin” as anti-infection and nasal-fed “oseltamivir” as antiviral treatment. ECG monitoring at 12:45 pm revealed that the heart rate increased to 190 beats/min, and the blood oxygen level continued to 80%. Chest X-ray re-examination showed that the bilateral lung infection was significantly worse than Yesterday’s chest film (Figure 1). With the consent of the family members, the patient was administered propofol sedation and tracheal intubation. After intubation, hemorrhagic secretions from the oral cavity and tracheal cannula were intermittently gushed in large quantities, and the patient was treated with an invasive ventilator. Acute bedside echocardiography findings showed reduced left ventricular systolic and diastolic functions (EF, 36%). The patient was successively administered tolasemide (40 mg) and morphine (5 mg) to reduce oxygen consumption. Rapid blood gas analysis at 13:37 pm showed the following results: pH 7.08, PO2 60 mmHg, and PCO2 55 mmHg. Slow vein input of 250 mL of sodium bicarbonate as a corrective treatment was administered considering metabolic acidosis. Concentrated salt supplementation was administered because the patient had low chlorine and sodium levels. After the treatment, the patient’s heart rate gradually decreased to normal, but the whole body was damp and cold. The patient was treated with noradrenaline and vasoactive dopamine drugs to prevent hypotension. The patient was agitated and sedated using propofol and midazolam. He was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further treatment (19:00 on June 15th) considering acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) with severe pneumonia, respiratory failure, metabolic acidosis, and cardiac insufficiency. After transfer to the ICU, ventilator-assisted ventilation was immediately connected and the patient’s oxygenation status was difficult to maintain. When transferring the patient to the ICU, physical examination and drug sedation were performed. The patient had a blood pressure of 136/71 mmHg and was administered dopamine and norepinephrine. The patient also had an oxygen saturation of 80%, multiple moist rales in both lungs, a heart rate of 130 beats/min, rhythm, strong heart sounds, abdominal softness, and borborygmus (four times/minute), but his limbs were not swollen. Laboratory examination showed influenza A virus antigen (-), TB-IgM, TB-IgG (-), and PCT 0.77. Blood culture showed no bacterial growth. D-dimer 23.55 mg/L, OB (+). Liver function, renal function, myocardial enzyme levels, and coagulation functions were significantly abnormal. The examination results since admission were as follows (Charts 1–3). The illness was interpreted by family members. The patient had acute onset of the disease, which progressed rapidly. The patient had sepsis with ARDS, respiratory failure, and heart, liver, and kidney function damage and was in a critical condition. Vancomycin+biapenem+ azithro

The patient’s condition gradually stabilized. After 2 mo, the patient recovered and went home.

The patient who was subjected to a thrilling rescue process eventually developed avian influenza. The most important finding was that the first symptom was occipital neuralgia. According to the literature, no relevant reports are available on avian influenza with occipital neuralgia. Occipital neuralgia is described as paroxysmal pain in the major distribution of the greater occipital nerves or lesser occipital nerves (LON). Ten percent of cases are due to LON[1-5]. Occipital neuralgia is paroxysmal, lasting seconds to minutes, and often consists of lancinating pain that directly results from the pathology of one of these nerves. The occipital nerve is separated from the anterior branch of the second cervical nerve through the superficial cervical plexus, and ascends around the posterior margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The distribution is in the mastoid process and posterior auricular region. Lower occipital neuralgia is a common type of neuralgia. The incidence of lesser occipital neuralgia is second only to that of great occipital neuralgia. The diagnostic criteria for lesser occipital neuralgia are unilateral or bilateral pain that meets the following criteria: (1) Pain is distributed in the small occipital nerve; (2) Pain has two of the following three characteristics: recurrent paroxysmal or persistent pain for several seconds to minutes; B - severe pain; C - sudden, penetrating, intense pain; and (3) Other diagnoses cannot be explained better.

The patient was diagnosed with lesser occipital neuralgia. Quantitative sensory analysis at the time of onset also indicated sensory hypersensitivity in the area of the lesser occipital nerve distribution (small fiber involvement). The effect of oxcarbazepine significantly supports this diagnosis. Occipital neuralgia can be classified into primary and secondary causes. Primary occipital neuralgia has fewer diseases, most of which are secondary to nerve damage. The anatomical structure of the occipital nerve leads to a high incidence of occipital neuropathy because the greater occipital nerve and lesser occipital nerve have to travel a considerable distance between muscles, tendons, and blood vessels after leaving the osseous structure to finally reach their respective dominant skin areas. The occipital nerve may be involved in this process, and pain may occur in any adjacent structure[6]. According to different secondary causes of occipital neuralgia, the disease can be divided into occipital muscle structure abnormalities, occipital bone structure abnormalities, occipital vascular structure abnormalities, occipital nerve structure abnormalities, and occipital suspension structure abnormalities[1,7-9]. For example, compression and deformities occur in the C2 region[1,10]. Cervical spondylotic radiculopathy is the most common cause of compression[11]. In addition, intramedullary lesions of the high cervical spinal cord can cause occipital neuralgia and even pressure on the helmet[12,13]. Abnormalities in occipital suspension structures have gained increasing attention[14]. The occipital nerve is enclosed by two layers of connective tissue lumen attached to the nerve intima. The fluid in the lumen is balanced by nutrient vessels and the absorption of arteries, the venous plexus, and nerves to avoid occipital nerve compression. The outer space is located in the epineurium. The connective tissue lumen is interdependent with other structures, such as the perineurium, subperineural space, nerve intima, and glia, which form local pressure. Suspension reticular structures can protect the occipital nerve and are vulnerable to the influence of adjacent structures or the external environment. Neck muscle strain, cold weather, ischemia, or cold fatigue can destroy the balance of the suspension network, increase intracavity pressure, and cause occipital nerve pain.

Our case of H7N9 avian influenza with severe occipital neuralgia as the first symptom is rare in the clinical setting. No relevant reports have been found in the literature at home and abroad. A case of occipital neuralgia caused by a herpes zoster virus infection has been reported[15]. The pathogenesis may be related to abnormal occipital suspension structure caused by respiratory virus infection. In addition, the lesser occipital nerve is separated from the anterior branch of the second cervical nerve through the superficial cervical plexus, bypassing the upward margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The superficial cervical plexus is located in the deep part of the sternocleidomastoid muscle behind the carotid sheath in front of the transverse process of the cervical spine, and deep cervical lymph nodes exist nearby. After respiratory tract infection, the lymph nodes are enlarged, possibly stimulating the nerves and further developing symptoms of occipital neuralgia. We believe that the etiology of occipital neuralgia is complex and could be the earliest manifestation of severe diseases. When occipital neuralgia is accompanied by fever, the possibility of infectious diseases should be considered.

The etiology of occipital neuralgia is complex and could be the earliest manifestation of severe diseases. When occipital neuralgia is accompanied by fever, the possibility of infectious diseases should be considered. Avian influenza is one of these causative agents.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ataei-Pirkooh A, Iran; Gambaryan AS, Texas S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Choi I, Jeon SR. Neuralgias of the Head: Occipital Neuralgia. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31:479-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Krymchantowski AV. Headaches due to external compression. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14:321-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pingree MJ, Sole JS, Oʼ Brien TG, Eldrige JS, Moeschler SM. Clinical Efficacy of an Ultrasound-Guided Greater Occipital Nerve Block at the Level of C2. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42:99-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24 Suppl 1:9-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 798] [Cited by in RCA: 2427] [Article Influence: 115.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hammond SR, Danta G. Occipital neuralgia. Clin Exp Neurol. 1978;15:258-270. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Johnstone CS, Sundaraj R. Occipital nerve stimulation for the treatment of occipital neuralgia-eight case studies. Neuromodulation. 2006;9:41-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cesmebasi A, Muhleman MA, Hulsberg P, Gielecki J, Matusz P, Tubbs RS, Loukas M. Occipital neuralgia: anatomic considerations. Clin Anat. 2015;28:101-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cohen SP, Plunkett AR, Wilkinson I, Nguyen C, Kurihara C, Flagg A 2nd, Morlando B, Stone C, White RL, Anderson-Barnes VC, Galvagno SM Jr. Headaches during war: analysis of presentation, treatment, and factors associated with outcome. Cephalalgia. 2012;32:94-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Magnússon T, Ragnarsson T, Björnsson A. Occipital nerve release in patients with whiplash trauma and occipital neuralgia. Headache. 1996;36:32-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Finiels PJ, Batifol D. The treatment of occipital neuralgia: Review of 111 cases. Neurochirurgie. 2016;62:233-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gande AV, Chivukula S, Moossy JJ, Rothfus W, Agarwal V, Horowitz MB, Gardner PA. Long-term outcomes of intradural cervical dorsal root rhizotomy for refractory occipital neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 2016;125:102-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hayashi Y, Koumura A, Yamada M, Kimura A, Shibata T, Inuzuka T. Acute-Onset Severe Occipital Neuralgia Associated With High Cervical Lesion in Patients With Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder. Headache. 2017;57:1145-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chalela JA. Helmet-Induced Occipital Neuralgia in a Military Aviator. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2018;89:409-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Abele H, Pieper KS, Herrmann M. Morphological investigations of connective tissue structures in the region of the nervus occipitalis major. Funct Neurol. 1999;14:167-170. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Ipekdal HI, Yiğitoğlu PH, Eker A, Ozmenoğlu M. Occipital neuralgia as an unusual manifestation of herpes zoster infection of the lesser occipital nerve: a case report. Acta Neurol Belg. 2013;113:201-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |