Published online Jul 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i19.4698

Peer-review started: March 25, 2023

First decision: April 20, 2023

Revised: April 29, 2023

Accepted: June 6, 2023

Article in press: June 6, 2023

Published online: July 6, 2023

Processing time: 97 Days and 7 Hours

Subcutaneous emphysema is a well-known complication of oral surgery, espe

In this paper, we report a 34-year-old female who underwent upper molar tooth preparation for crowns and subsequently developed extensive subcutaneous emphysema on the retromandibular angle on two different occasions. The treatment plan for this patient involved close observation of the airway, and administration of dexamethasone and antibiotics via intravenous drip or orally. Ice bag compression was quickly applied and medication was prescribed to alleviate discomfort and promote healing. Although the main reason is unclear, the presence of a fissure in the molar is an important clue which may contribute to the development of subcutaneous emphysema during crown preparation. It is imperative for dental professionals to recognize such pre-disposing factors in order to minimize the risk of complications.

This case highlights the need for prompt diagnosis and management of subcutaneous emphysema because of the risk of much more serious compli

Core Tip: Subcutaneous emphysema secondary to dental procedures such as crown preparation is rare. In this paper, we report a 34-year-old female who underwent upper molar tooth preparation for crowns and subsequently developed extensive subcutaneous emphysema on the retromandibular angle on two different occasions. Prompt diagnosis and management of subcutaneous emphysema is necessary for dentist.

- Citation: Bai YP, Sha JJ, Chai CC, Sun HP. With two episodes of right retromandibular angle subcutaneous emphysema during right upper molar crown preparation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(19): 4698-4706

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i19/4698.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i19.4698

Subcutaneous emphysema is a rare but serious complication of dental and oral surgery that can arise during tooth extraction, crown preparation, and endodontic therapy[1]. High-speed air turbine drills are widely used during dental procedures such as exodontia, tooth sectioning, and dental restoration. The drills are driven by compressed air (rate of 3.5-4.0 kgf/cm2, rotation speed of 450000 rpm)[2]. The use of high-speed air turbines appears to be associated with most cases of subcutaneous emphysema; pressurised air is blown into the deep space[3].

The maxillofacial fascial spaces are close to the retropharyngeal space and mediastinum. Therefore, air and water that enter the maxillofacial spaces could trigger deep space infections with serious life-threatening complications[4]. Subcutaneous emphysema caused by dental procedures can involve the facial area, orbital region[5], neck[6], and (rarely) mediastinum[7]. One case of vision loss caused by optic nerve damage has been reported[8]. Sometimes, all of these complications develop simultaneously[9], and are then very difficult to manage[10]. Fortunately, most emphysema is self-limiting, benign, and resolves safely[11]. The most common symptom of subcutaneous emphysema is some degree of rapid swelling that generates crepitus when pressed by the fingers[4]. Most cases occur after mandible third molar extraction while using an air turbine; the deep facial and soft tissue spaces swell in such cases[1-3]. Conventional case management for subcutaneous emphysema including: (1) Immediate recognition: Quickly identify the signs and symptoms of subcutaneous emphysema, such as swelling, crepitus on palpation, and potential difficulty in breathing; (2) Airway monitoring: Closely monitor the patient’s airway to ensure there is no obstruction or compromise due to the swelling; (3) Administration of medications: Prescribe medications, such as anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., corticosteroids like dexamethasone) and antibiotics (e.g., cefuroxime), to manage inflammation and prevent infection; and (4) Follow-up care: Schedule follow-up appointments to monitor the patient’s progress and ensure resolution of the subcutaneous emphysema and any potential complications.

We here present a rare case of subcutaneous emphysema that occurred twice during crown preparation of the right upper molars (teeth #16 and #17); sudden swellings developed around the mandibular angle while the patient was being treated. Crown preparation is generally considered a low-risk procedure for subcutaneous emphysema compared to tooth extractions, particularly when involving impacted third molars. The likelihood of air being forced into the fascial spaces is lower during crown preparation compared to more invasive procedures.

Repeated instances of subcutaneous emphysema in the same patient during similar dental procedures are unusual. Most patients who experience this complication once are unlikely to encounter it again, particularly if the dental professional is aware of the previous occurrence and takes extra precautions during subsequent treatments.

Individual patient factors may contribute to the rarity of this occurrence[11]. Some patients might have anatomical variations or predisposing factors that make them more susceptible to subcutaneous emphysema during dental procedures. In this report, case management was also described, along with the diagnosis. The purpose of this report is to alert the dental community about the incidence of subcutaneous emphysema from a routine dental procedure, and how to recognize and manage its occurrence.

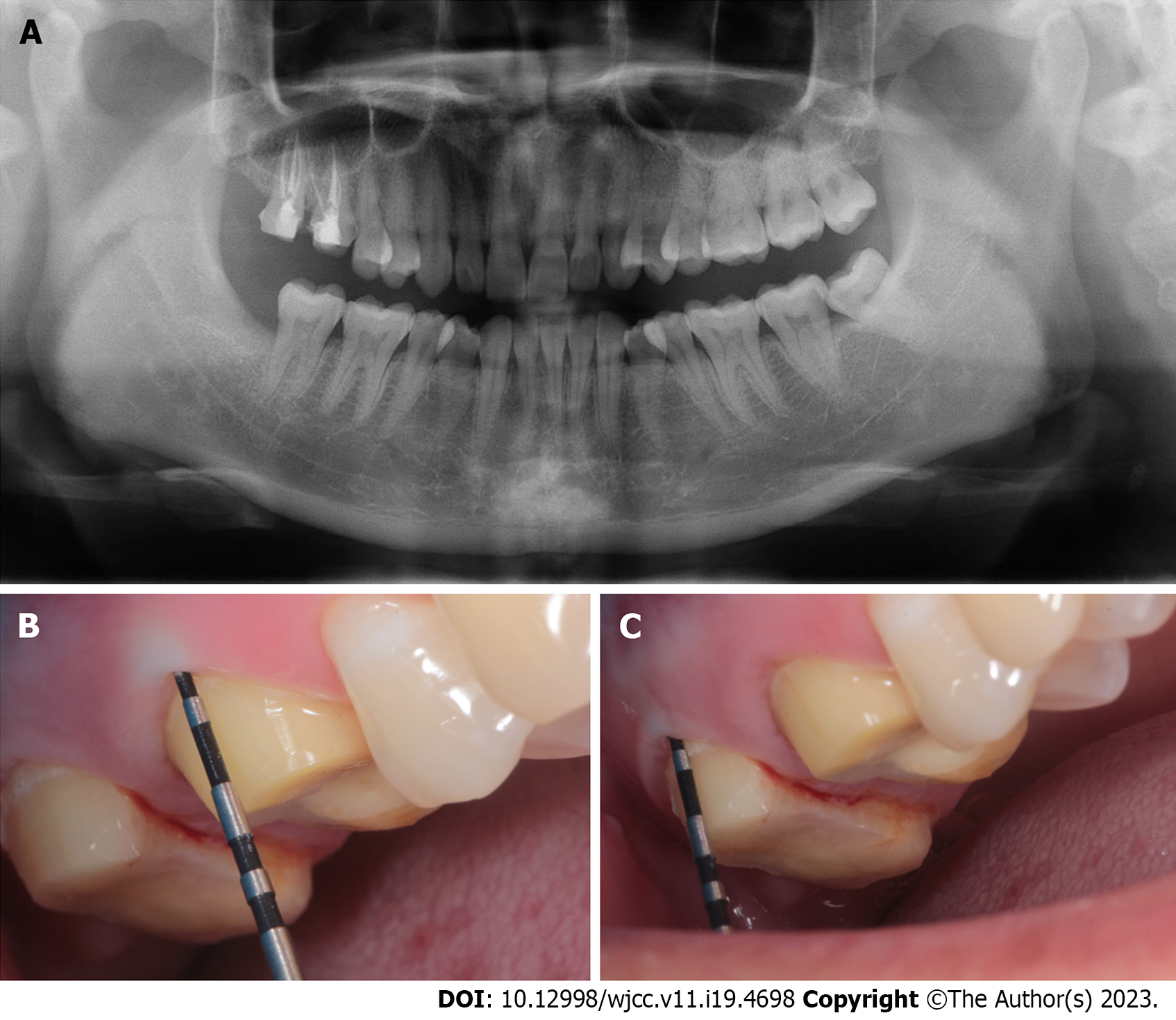

A 34-year-old female with no medical history consulted us for crown restoration of the right upper molars (teeth #16 and #17) after successful endodontic treatment. The patient stated that these teeth were painful when biting even soft food. The distal surface of #16 and medial surface of #17 had undergone composite resin restoration. Both teeth were mildly painful on percussion, but were not loose. The gingiva was healthy, exhibiting a normal colour and gingival sulcus depth. There was no bleeding on probing. We obtained a panoramic radiograph and periapical films before operations (Figure 1).

Crown preparation proceeded smoothly until the occlusion face of #17 was ground; the patient reported a sudden transient pain at this point. The operation was stopped and we immediately examined the patient. She was alert and complained of a bump in the right retromandibular angle that gradually hardened, but was not in pain and spoke in full sentences.

There is no past illness.

There is no personal and family history.

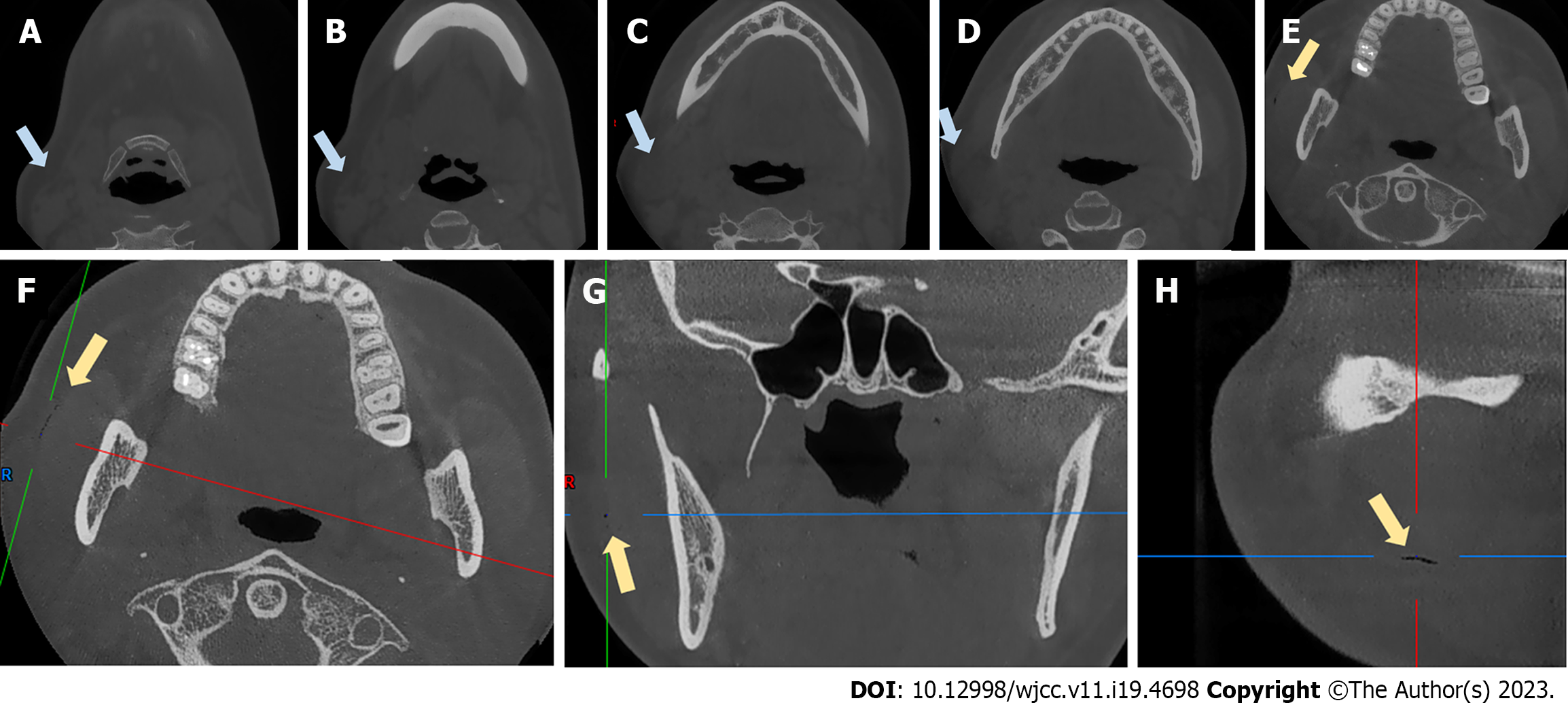

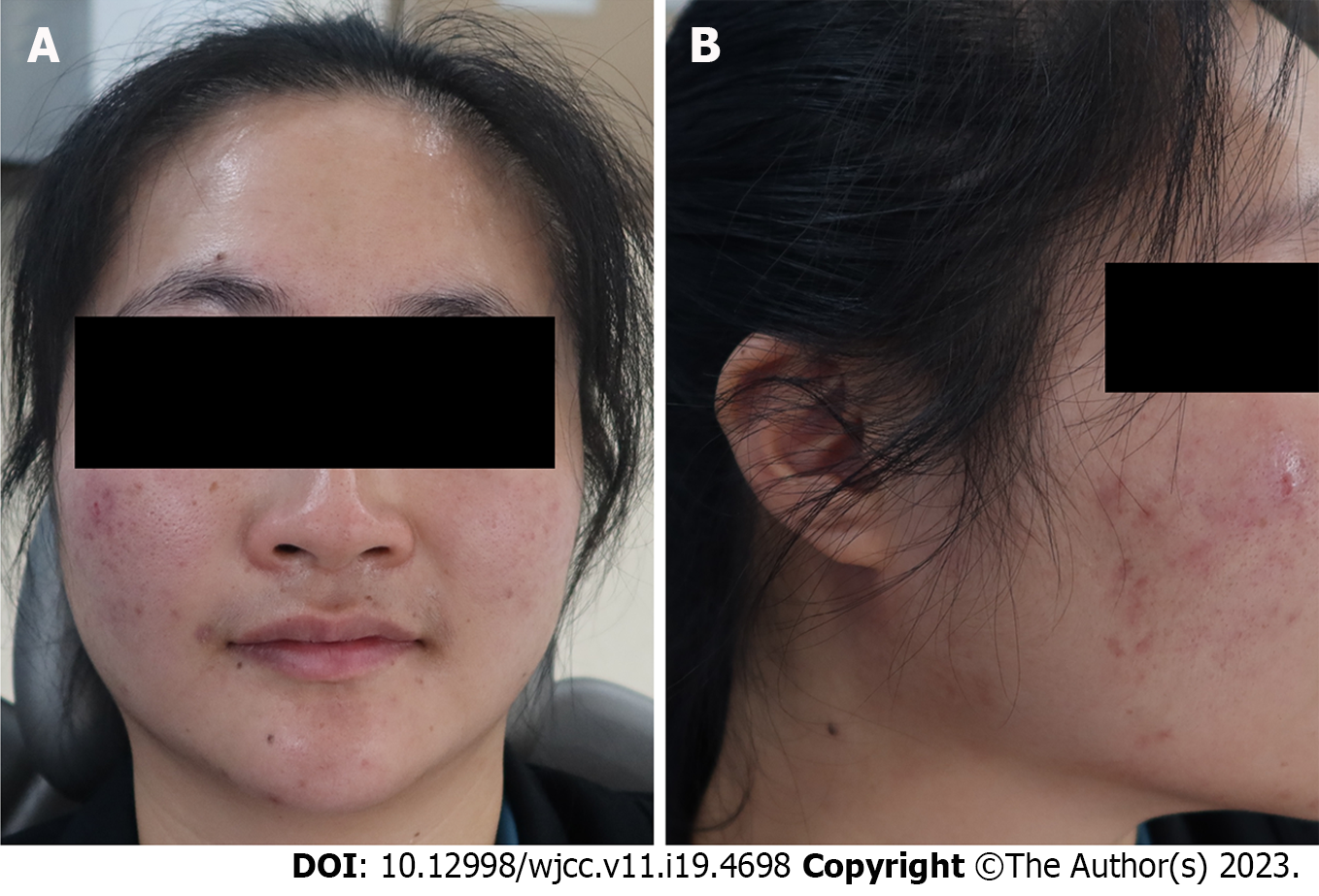

The tissue around the right retromandibular was obviously swollen, but was non-erythematous and non-tender. On palpation, there was a sensation of crepitation. The patient did not experience much pain, and had no difficulty with mouth-opening or breathing (Figure 2).

As crepitations were noted during palpation, we diagnosed subcutaneous emphysema. The operation was immediately interrupted; the patient’s blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, and oxygen saturation were normal. No deep periodontal pocket was found around the tooth (Figure 3 and Table 1).

| Teeth | Mesio-buccal site | Buccal centre | Distal-buccal site | Mesio-lingual site | Lingual centre | Distal-lingual site |

| #16 | 2.8 mm | 2.0 mm | 2.5 mm | 2.5 mm | 2.2 mm | 3.0 mm |

| #17 | 2.7 mm | 2.8 mm | 2.7 mm | 3.0 mm | 2.5 mm | 3.2 mm |

We performed cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) after the emphysema developed, which revealed obvious swelling and thickening of soft tissue on the masseter muscle and a discrete region of emphysema in the layer between the masseter muscle and subcutaneous fascia (Figure 4).

The treatment plan was close observation of the airway, and dexamethasone (10 mg/d) and antibiotics (cefuroxime 1.5 g/d) for 3 d. This approach aimed to manage inflammation and reduce the risk of infection. Ice bag compression was quickly applied and medication was prescribed to alleviate discomfort and promote healing.

The patient was not admitted but visited our outpatient clinic daily for intravenous drip therapy. After 3 d of treatment, the swelling had completely disappeared and there were no complications (Figure 5).

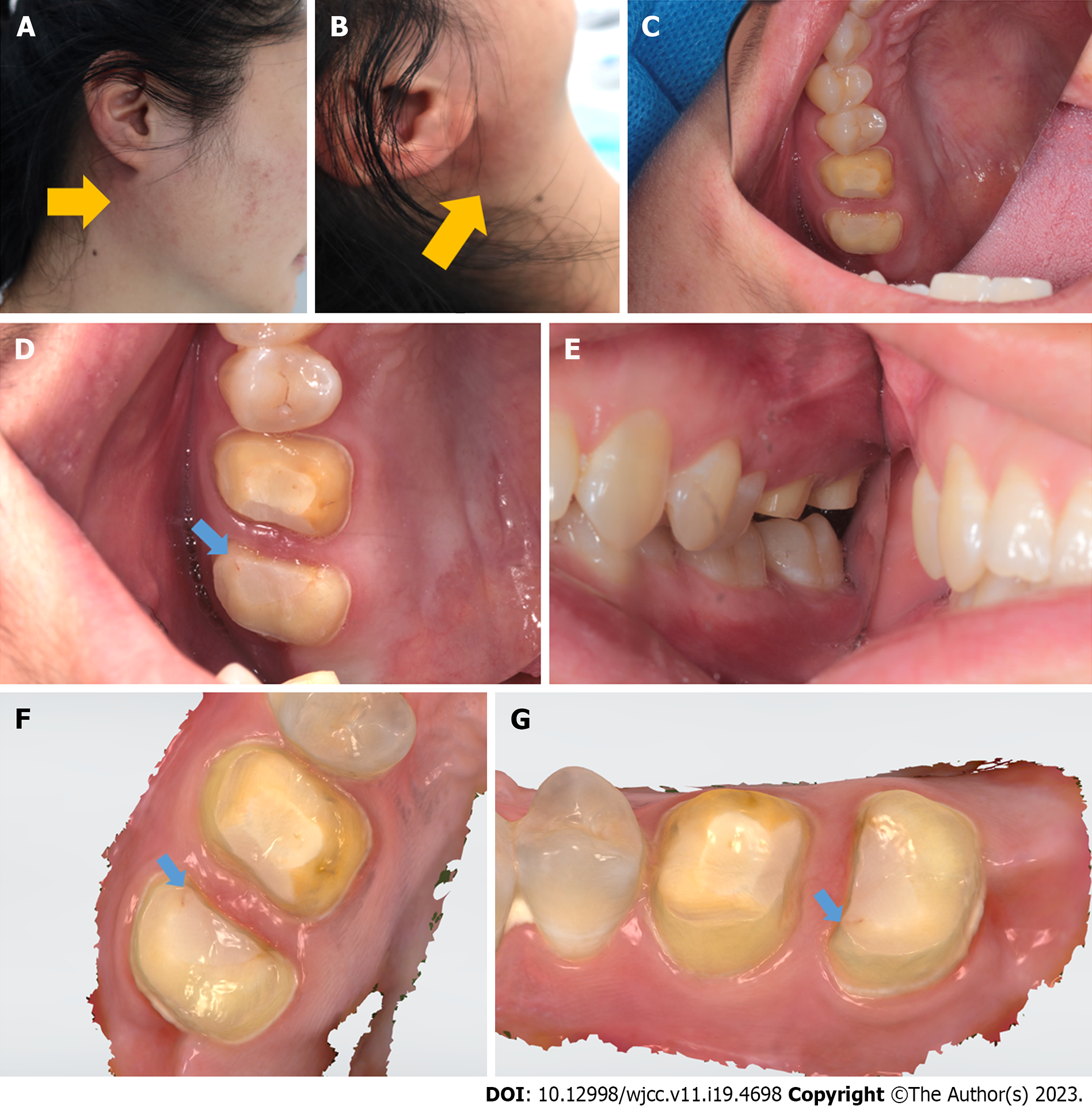

After 2 wk of observation, the swollen tissue in the right retromandibular angle had recovered well. As tooth preparation had not been concluded, the patient again visited our outpatient clinic to finalise the prosthodontic procedure prior to crown placement on the right upper molars. On this occasion, we proceeded with great care. When gently and slowly grinding the occlusion surface of the medial-buccal cusp of #17 with a low-speed turbine and normal water and air flow, the patient again reported a sudden pain in the right retromandibular angle.

The affected area exhibited a striking similarity to previous instances, with the skin turning noticeably red and gradually swelling up as a reaction to the underlying issue. After a few seconds, crepitation was observed, which is a crackling sound produced when air is trapped under the skin. This is a classic sign of subcutaneous emphysema, a medical condition that occurs when air infiltrates the subcutaneous tissue layer beneath the skin. Therefore, we confirmed that the patient had subcutaneous emphysema in the same area once again.

We stopped the operation and applied an ice bag (cold compress) to the swelling. Ibuprofen and cephalosporin were immediately given orally. After 2 h of observation, the swelling was limited to a very small area and the temperature of the skin had normalised, but the swelling was light red in colour and the tissue was hard when palpated. As before, no deep periodontal pocket or gingival inflammation around the tooth were found (Figure 6).

At the 1-wk follow-up, the symptoms had disappeared and there were no other complications. The patient then re-visited us and we placed provisional crowns.

Dental procedures can disrupt the mucosa of the oral cavity and introduce air into connective tissue spaces, thereby triggering subcutaneous emphysema. Although this is generally benign, there is a risk of progression to serious consequences including pneumothorax, air embolism, mediastinitis, cranial nerve palsy, and cardiac tamponade[12]. Subcutaneous emphysema spreads near sites where valves are located. When the upper teeth are involved, periorbital swelling is the most common symptom; when the lower teeth are implicated, cheek and neck bulges are more common[3]. Subcutaneous emphysema developed during crown preparation for teeth #16 and #17 is rare, especially when addressing an occlusion surface, but the emphysema affected the right retromandibular angle rather than the periorbital area (which was the most frequently affected area in previous studies). The reason for this is unclear; we offer two possible hypotheses. First, strong air flow into the gingival sulcus destroyed a loose connective tissue attachment. Then, gingival tissue was detached from the bony maxillary tubercle bone and air entered the layers between the buccinator muscle and buccal fat tissue. The gingival valve closed immediately, triggering the valvular effect described in other clinical situations[3]. The air did not travel beneath the buccinator muscle along the bone; if it had done so, emphysema would have occurred in the infraorbital area. The air spread to the masseter muscle layer along the buccinator muscle fascia to reach the posterior edge of the mandible. The reason why the swelling was confined to this area, and thus did not spread into the deeper cervical region, was because we stopped the operation immediately, and thus the air volume was limited. The other hypothesis involves the subfissure of tooth #17 (Figure 6). When preparing the occlusion surface, the turbine moved the tooth, thereby increasing the size of the subfissure, and air entered deep tissue to cause subcutaneous emphysema. The air pathway in this case would be the same as that described above. This hypothesis may be supported by the fact that both emphysema episodes started during preparation of the occlusion surface of #17, but the gingival sulcus depths of #16 and #17 were healthy and normal. The patient also reported pain in the right upper molar when biting, especially on hard food. However, the root canal treatment had been successful, so we suspect that the subfissure hypothesis may be correct. We plan further studies to test this hypothesis.

As stated by Fasoulas et al[13], subcutaneous emphysema is almost twice as common in females than males. In their systematic review, emphysema was mainly reported in females (39/65) rather than males (20/65) and the age of the patients ranged from 18 to 63 years (mean = 38 years). In another study, Jeong et al[11] indicated that subcutaneous emphysema originating from maxillary teeth (n = 8; 66.7%) was two times more common than that originating from mandibular teeth (n = 4; 33.3%), meanwhile subcutaneous emphysema was more common in posterior teeth (91.7%, n = 11) than in anterior teeth (8.3%, n = 1). Approximately 18% (2 of 11 patients) of subcutaneous emphysema cases can be attributed to crown preparation[11]. Nadarajah reported a serious and huge cervical subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum occurring after extraction of a mandibular right molar by using an air turbine handpiece[10]. Although there are no documented cases in the literature, it is important for dental professionals to be aware that cervical subcutaneous emphysema caused by dental crown preparation can also potentially lead to very serious complications. Rapid diagnosis, management is critical for both patient and dentist.

The rationale for antibiotic therapy is that introduced air may contain bacteria, which could trigger rapidly spreading cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis[1]. Fasoulas et al[13] prescribed antibiotics to 40 cases for 2-10 d, depending on the severity of the condition. Βeta-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin and amoxicillin, as well as various cephalosporins (given orally or intravenously), were the most common choices. Analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cold or hot compresses, pressure or massage of the swollen area, and ice bag treatment have been recommended by some studies. Based on our experience, when crown preparation triggers subcutaneous emphysema, immediate cessation of the operation and application of an ice bag to compress the swelling controls the emphysema very effec

Subcutaneous emphysema can also be induced by sneezing, blowing forcefully, coughing, or vomiting after a dental procedure[1]. Dentists may attribute immediate swelling after a dental operation to angioedema or an allergic reaction, and delayed symptoms to a hematoma or soft tissue infection such as cellulitis or Ludwig’s angina. Patients with subcutaneous emphysema typically exhibit painless oedema of the face and neck; the palpable crepitus is pathognomonic, which clearly distinguishing emphysema from other conditions[13]. However, dental professionals should be vigilant if a patient complains of breathing difficulties; the emphysema may have spread to the paratracheal, mediastinal, or thoracic spaces.

In most cases, air re-absorption begins within 2-3 d and is frequently complete by day 7-10 after onset[11]. Oxygen inhalation via a nasal cannula accelerates this process by reducing the blood nitrogen pressure, thus enhancing air re-absorption[14].

When encountering iatrogenic air emphysema, airway restriction must be considered. CBCT is useful to determine the extent of the damage. Also, patients should be told to avoid any activity after treatment that might increase the oral cavity pressure, including coughing, smoking, nose-blowing, the use of a straw, and vomiting.

Subcutaneous emphysema in the posterior region of the right retromandibular angle during molar crown preparation in #16 and #17 is rare. Caution should be exercised when using air turbines. Rapid diagnosis and appropriate management reduce the risk of serious complications.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ardila CM, Colombia; Rakhshan V, Iran S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | McKenzie WS, Rosenberg M. Iatrogenic subcutaneous emphysema of dental and surgical origin: a literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1265-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Romeo U, Galanakis A, Lerario F, Daniele GM, Tenore G, Palaia G. Subcutaneous emphysema during third molar surgery: a case report. Braz Dent J. 2011;22:83-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sarfi D, Haitami S, Farouk M, Ben Yahya I. Subcutaneous emphysema during mandibular wisdom tooth extraction: Cases series. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;72:103039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | D'Agostino S, Dolci M. Subcutaneous Craniofacial Emphysema Following Endodontic Treatment: Case Report with Literature Review. Oral. 2021;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Chang CH, Lien WC. Palpebral emphysema following a dental procedure. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36:908.e1-908.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Singh V, Ganti L, Haupt JD, Marshall B. Iatrogenic post-pulpectomy cervicofacial subcutaneous emphysema in a paediatric patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rawlinson RD, Negmadjanov U, Rubay D, Ohanisian L, Waxman J. Pneumomediastinum After Dental Filling: A Rare Case Presentation. Cureus. 2019;11:e5593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rubinstein A, Riddell CE, Akram I, Ahmado A, Benjamin L. Orbital emphysema leading to blindness following routine functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | An GK, Zats B, Kunin M. Orbital, mediastinal, and cervicofacial subcutaneous emphysema after endodontic retreatment of a mandibular premolar: a case report. J Endod. 2014;40:880-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nadarajah A, Arron TY, Elston T. Huge surgical emphysema and pneumomediastinum as a sequela to conservative dental restoration: A case report. J Case Rep Images Surg. 2022;8:1-4. |

| 11. | Jeong CH, Yoon S, Chung SW, Kim JY, Park KH, Huh JK. Subcutaneous emphysema related to dental procedures. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;44:212-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tomasetti P, Kuttenberger J, Bassetti R. Distinct subcutaneous emphysema following surgical wisdom tooth extraction in a patient suffering from 'Gilles de la Tourette syndrome'. J Surg Case Rep. 2015;2015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fasoulas A, Boutsioukis C, Lambrianidis T. Subcutaneous emphysema in patients undergoing root canal treatment: a systematic review of the factors affecting its development and management. Int Endod J. 2019;52:1586-1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Brzycki RM. Case Report: Subcutaneous Emphysema and Pneumomediastinum Following Dental Extraction. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2021;5:58-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |