Published online Jun 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i18.4350

Peer-review started: February 25, 2023

First decision: April 11, 2023

Revised: April 23, 2023

Accepted: May 9, 2023

Article in press: May 9, 2023

Published online: June 26, 2023

Processing time: 121 Days and 14.1 Hours

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are one of the modern treatment methods for advanced malignancies. However, this group of medications is also associated with various immune-related adverse events, such as colitis or pneumonitis. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced gastritis is a less common adverse event.

We describe a 64-year-old woman presenting with diarrhea, nausea, and discomfort in the upper abdominal region. The patient had a history of metastatic lung cancer, which was treated with nivolumab. During the first endoscopy, an infiltrating gastric tumour was suspected. Later, based on endoscopic, histological and radiological findings, nivolumab-induced gastritis was diagnosed. The patient was successfully treated with three courses of omeprazole.

As a consequence of the increased use of immune checkpoint inhibitors, a growing number of reported immune-related adverse events could be expected. The diagnosis of immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced gastritis should be considered when assessing a patient treated with nivolumab with upper gas

Core Tip: Nivolumab-induced gastritis is a less common immune-related adverse event of nivolumab. The most common symptoms include nausea, pain, diarrhea, loss of appetite, and weight loss. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and biopsy are the most important diagnostic tools. In most cases, gastritis is treated with corticosteroids in combination with proton pump inhibitors. In our case, the patient was successfully treated with omeprazole monotherapy.

- Citation: Cijauskaite E, Kazenaite E, Strainiene S, Sadauskaite G, Kurlinkus B. Nivolumab-induced tumour-like gastritis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(18): 4350-4359

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i18/4350.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i18.4350

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are a novel treatment option for various types of cancer, including non-small cell lung carcinoma[1]. ICIs, such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors, facilitate cancer cell destruction through either CTLA-4 or PD-1 receptor pathway blockade, thus reversing cancer tolerance of the immune system. However, due to the ICIs mechanism of action, the toxicity of therapy is also immune-mediated[2,3].

We present a patient who developed ICI-induced gastritis after nivolumab immunotherapy and was successfully treated with proton pump inhibitor (PPI) monotherapy (Table 1). We also provide a short review of the literature that is similar to the cases already described by other authors (Table 2).

| Date | Event | Findings |

| December 2017 | Chest CT | Tumour in the left lung (S1/2) with pleural metastases |

| January 2018 | Fibrobronchoscopy with biopsy | Pathology report: poorly differentiated (G3) non-small lung cell adenocarcinoma, EGFR (-) |

| February - June | Chemotherapy treatment (Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Bevacizumab), 6 courses | |

| September | Chest CT | Reduction of target tumours by 16%. Stable oncologic disease |

| January 2019 | Chest CT | Progression of the disease |

| January | Initiation of nivolumab treatment | |

| December 2020 | Beginning of gastrointestinal symptoms | |

| February 2021 | EGD with biopsy | EGD: Tumour-like endoscopic changes in the stomach; Histology: Chronic active (++) erosive gastritis with gland destruction and lymphoepithelial infiltration. Possible immune check-point inhibitor therapy-associated gastritis |

| March | Abdominal CT | Stomach changes related to chronic gastritis |

| March | EGD with biopsy | EGD: Progression of tumour-like endoscopic changes in the stomach; Histology: Chronic active (++) gastritis with erosions and intestinal metaplasia |

| March - April | First course of 20 mg/d of omeprazole | |

| July | EGD with biopsy | EGD: Decreased diffuse inflammatory/infiltrative changes in the stomach wall; Histology: Chronic active gastritis (++) associated with immunotherapy |

| July - August | Second course of omeprazole 20 mg/d | |

| September | COVID-19 infection; acute renal failure; cessation of nivolumab | |

| October | Third course of omeprazole 20 mg/d | |

| December | Chest CT | No progression of pulmonary disease |

| Renal function improvement; Reintroduction of nivolumab | ||

| January 2022 | EGD with biopsy | EGD: Gastric mucosa atrophy with focal intestinal metaplasia, gastric polyp; Histology: Hyperplastic gastric polyp |

| March | Acute renal failure; kidney biopsy; cessation of nivolumab | Histology: Insignificant and non-specific renal changes |

| May | Renal function improvement; Initiation of Atezolizumab treatment | |

| October | Chest CT | No progression of pulmonary disease |

| Ref. | Main symptoms | Time of onset (in relation to nivolumab therapy) | Radiologicall findings | EGD findings | Pathology findings | Treatment | Outcomes |

| Johncilla et al[2], 2019 | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea | Two doses | - | Gastric erythema and erosions | Focal enhancing gastritis (pyloric antrum and body) | Prednisone, infliximab | Improved symptoms |

| Zhang et al[17], 2019 | Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting | Avg. 8 doses | - | Erythema (with or without erosions) - 64% of patients, periglandular inflammation -20%, polyps - 2% | Periglandular inflammation, granuloma, diffuse inflammation, neutrophilic abscess | Steroids, infliximab | - |

| Placke et al[4], 2021 | Weight loss, nausea, heartburn | 118 d | - | Severe erythematous gastritis | Lymphoplasmocytic cells, granulocyte infiltration | Pantoprazole, prednisone | Improvement in symptoms (after circa 6 d) |

| Shi et al[3], 2017 | Vomiting, nausea | 17 cycles | PET/CT and MRI - unremarkable | Diffusely friable, erythematous, denuded gastric mucosa | Neutrophilic abscesses, expansion of the lamina propria with lymphocytes and plasma cells | Pantoprazole and ranitidine; cessation of nivolumab | No improvement after pantoprazole and ranitidine therapy; improvement after nivolumab cessation |

| Boike et al[10], 2017 | Dysphagia, diarrhea | 6 mo | PET/CT - FDG uptake in the esophagus and stomach wall | Gastric erythema, thick mucoid secretions | Lymphoplasmocytic infiltration in lamina propria and epithelium | Prednisone and PPI | Improved symptoms after 2 d |

| Alhatem et al[6], 2019 | Loss of appetite, diarrhea, bloating | Few months | - | Barrett’s esophagus, antral gastritis | Transmural inflammation, cryptitis, dysplasia | Prednisone; cessation of nivolumab for 6 wk | Improved symptoms; no recurrence after resuming nivolumab therapy |

| Woodford et al[5], 2021 | Epigastric pain, intermittent anorexia and nausea | 4 cycles (nivolumab and ipilimumab combination) | CT - stomach wall thickening | Erythema, friable gastric mucosa | Active chronic inflammation, distortion of glandular architecture | Pantoprazole; methylprednisone | Pain aggravation after 2 wk. Recurrent gastritis 12 mo later |

| Bazarbashi et al[14], 2020 | Mild epigastric discomfort | 4 doses of nivolumab monotherapy (16 wk) then switched to nivolumab and + ipilimumab combination (2 doses, 4 wk) | Abdominal and pelvic CT - unremarkable | Hemorrhagic and inflamed gastric mucosa with exudate | Active chronic inflammation, intraepithelial lymphocytosis, increased apoptotic activity | Prednisone | Improved symptoms. Continual endoscopically observed resolution of inflammation |

| Rovedatti et al[7], 2020 | Epigastric pain, loss of appetite | 12 cycles | - | Diffuse ulcerations covered with fibrin-like membranes, erythematous friable gastric mucosa | Lymphoplasmocytic and neutrophilic infiltration, microabscesses, apoptotic bodies, reactive epithelial cell atypia | Prednisone, pantoprazole, cessation of nivolumab | Improved symptoms. Endoscopic and histologic remission. |

| Vindum et al[8], 2020 | Anorexia, vomiting, nausea, epigastric pain, weight loss | 6 doses | PET/CT - FDG-uptake in the gastric wall | Erythematous gastric mucosa with fibrinous erosions | Chronic active pangastritis. Neutrophilic and lymphocytic epithelial infiltration, crypt abscesses, lymphoplasmacytic infiltration in lamina propria | 1st admission – low dose prednisone; 2nd admission - high dose methylprednisone (80 mg), pantoprazole | Improved symptoms after 3 mo of treatment. Radiological and clinical remission |

| Mubder et al[15], 2020 | Anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain | 3 mo | Abdominal and pelvic CT - unremarkable | Active gastritis | Severe acute gastritis with necro-inflammatory debris. Glandular destruction, lymphoplasmacytic infiltration | - | - |

| Martínez-Acitores de la Mata et al[16], 2020 | Epigastric pain, hyporexia, vomiting | 2.5 yr | Abdominal CT - unremarkable | Exudate, diffuse congestion, edema, erythema, friable mucosa in the stomach | Glandular destruction, crypt abscesses, inflammatory cell infiltration. | PPI, cessation of nivolumab | Improved symptoms |

| Ferrian et al[18], 2021 | Epigastric pain, nausea, anorexia | 32 mo | - | Erythema, friable gastric mucosa | Crypt destruction, erosions, neutrophilic, lymphoplasmacytic, and eosinophilic infiltration in the lamina propria | Prednisone, cessation of nivolumab | Improved symptoms. Radiological and clinical remission |

| Ebisutani et al[13], 2020 | Left-sided epigastric pain, nausea, anorexia | 7 mo | CT - thickening of the gastric wall | Erythema, edema, white membrane in the gastric mucosa | Lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltration of the lamina propria and epithelium | Prednisone, cessation of nivolumab | Improved symptoms. Endoscopic and clinical remission |

| Kobayashi et al[9], 2017 | Epigastric pain, hematemesis | 10 cycles, 4 mo | - | Hemorrhagic gastritis, white membrane on mucosa | Lymphoplasmacytic and neutrophilic infiltration | Prednisone | Improved symptoms after few days. Clinical and endoscopic remission |

| Tomiyasu et al[11], 2021 | Diarrhea, nausea, anorexia, weight loss | 11 courses | PET/CT - diffuse FDG accumulation in stomach wall and duodenum | Multiple white granular elevations in the stomach | Eosinophilic infiltration of mucosa | Prednisone, cessation of nivolumab | Improved symptoms |

| Cǎlugǎreanu et al[12], 2019 | Vomiting, epigastric pain, weight loss | 26 courses | PET/CT – diffuse FDG uptake in the stomach wall | Ulcerative and hemorrhagic gastritis | Lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with scattered neutrophils and eosinophils | Methylprednisone and PPI, cessation of nivolumab | Resolved after 8 wk |

| Tsuji et al[20], 2022 | Anorexia, epigastric discomfort, vomiting | 10 mo | CT - diffuse thickening of the stomach wall; EUS - mucosal thickening | Mucosal edema, erosions | Inflammatory cell infiltration of the lamina propria | Prednisone, cessation of nivolumab | Improved symptoms. Radiological and endoscopic remission |

| Samonis et al[21], 2022 | Anorexia, gastric discomfort and pain, vomiting | 6 mo | PET/CT - intense metabolic uptake in the stomach | Erythematous gastritis, friable mucosa, edema, mucous exudate | Inflammatory cell infiltration of the lamina propria | Prednisone and PPI | Improved symptoms. Endoscopic remission |

A 64-year-old Caucasian woman experiencing diarrhea, nausea, early satiety and discomfort in the upper abdominal region was referred for a gastroenterologist consultation by her pulmonologist.

The patient was diagnosed with poorly differentiated metastatic non-small cell lung carcinoma (G3) (T2aN1M1a) in 2018. She received chemotherapy with carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab. After the initial good response, the oncological disease relapsed in 2019, and treatment with nivolumab was started. At first, the patient tolerated immunotherapy well, but after the seventh course of nivolumab, the patient was diagnosed with diabetes possibly caused by immunotherapy-associated beta cell destruction. Diabetes was managed with insulin therapy. In December 2020, after 64 courses of nivolumab therapy, the patient started experiencing diarrhea, nausea without vomiting, early satiety and upper abdominal discomfort. In February 2021, after performing an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with biopsy, the patient was diagnosed with ICI-induced gastritis. Initial omeprazole treatment was effective and well tolerated, and thus continued. During the following years, several EGDs with biopsies and abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans were performed to evaluate the endoscopic, pathohistological, and radiological response to treatment and the natural course of the disease. The course of the disease and its treatment are presented in Table 1.

The patient denied any other chronic diseases or the concomitant use of other medications. She underwent conization of the cervix and tonsillectomy.

The patient denied allergy to food or drugs. She developed a rash after the first course of chemotherapy. Her family history was insignificant.

The patient was slightly underweight (body mass index 18.22 kg/m2). No other significant changes were detected.

No remarkable abnormalities were observed in the patient’s recent blood laboratory examination results.

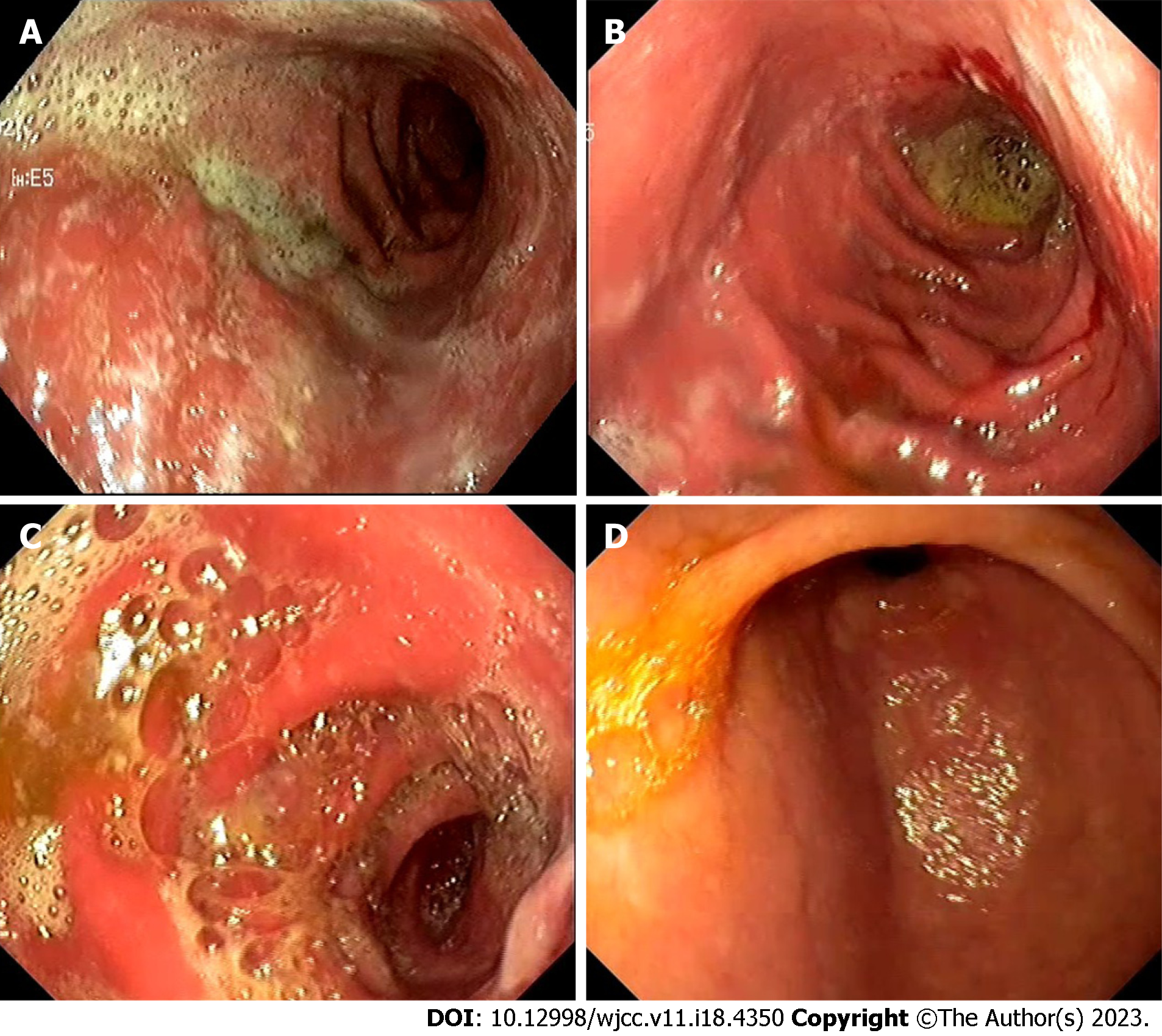

To evaluate the possible origin of symptoms related to upper gastrointestinal tract dysfunction, an EGD with multiple biopsies was performed[1]. Colonoscopy was not performed due to typical upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Tumour-like endoscopic changes in the stomach were found. The stomach mucosa was covered with whitish plaques throughout the entire stomach, affecting the course of the gastric folds in the upper curve. However, following air insufflation, the folds were almost completely smoothed out. In the pre-papillary region, the mucosa was thicker (Figure 1A). An infiltrating stomach neoplasm was suspected; therefore, an abdominal CT scan was performed. The scan revealed stomach changes related to chronic gastritis: the wall of the pyloric part of the stomach was evenly thickened, and edematous, the mucosa clearly differentiated, diffusely and more intensively accumulated contrast material, and clear masses were not differentiated. The stomach body wall was evenly stretched, not thickened (Figure 2).

Pathohistological examination of biopsies from the first upper gastrointestinal endoscopy excluded the suspected gastric tumour. It showed active chronic gastritis with erosions, lymphatic follicles and lymphoepithelial lesions. The possibility of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma was excluded by immunohistochemical analysis. Helicobacter pylori infection was not reported.

After evaluation of EGD, abdominal CT and pathohistological results, the patient was diagnosed with ICI-induced gastritis.

Due to the mild symptoms experienced by the patient and the satisfactory results reported by other clinicians, the patient was treated with three courses of omeprazole: first – March-April 2021 (60 d, 20 mg/day), second – July-August 2021 (60 d, 20 mg/day), third – October 2021 (30 d, 20 mg/day). The first and second courses were prescribed by the gastroenterologist, and the third course was initiated by the patient herself whenever she felt the recurrence of related symptoms. The patient was also referred to a nutritionist for evaluation of possible malnutrition.

Several follow-up EGDs with multiple gastric mucosa biopsies were performed to evaluate the dynamics of stomach changes due to treatment and the general natural course of the disease.

The second EGD (March 2021) revealed negative endoscopic changes in the stomach – a progression of tumour-like changes (Figure 1B). New endoscopic abnormalities such as fragile and prone to bleeding mucosa were observed together with changes described previously. Biopsies showed active chronic gastritis with erosions and intestinal metaplasia, and immunohistochemical analysis rejected cytomegalovirus infection.

The third EGD (July 2021) showed a decrease in diffuse inflammation and infiltration of the stomach wall (Figure 1C). There was no bleeding at contact, erosions, or white plaques. Additionally, a polyp 0.5 cm in diameter was discovered. Biopsies revealed active chronic non-erosive gastritis with pyogenic granuloma and a hyperplastic polyp.

During the fourth EGD (January 2022) gastric mucosal atrophy was observed with some spots of intestinal metaplasia and a 1.0 cm polyp (Figure 1D). The histological report was compatible with a hyperplastic gastric polyp.

Treatment with omeprazole was effective, resulting in symptom relief after several weeks. The patient received three courses of omeprazole and is now in remission with no significant gastro

As the use of ICIs rises, an increasing number of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) have been reported[1]. ICIs, namely nivolumab, the PD-1 receptor inhibitor, may cause irAEs in various organ systems, for example, the colon, skin, liver, and thyroid gland. The most common side effects of nivolumab are diarrhea (incidence rate approximately 10%-13%) that can be associated with ICI-induced colitis[4], skin rash and pruritus (approximately 2%), hypothyroidism (< 2%), hepatitis (< 2%), pneumonitis (approximately 3%), and renal failure (approximately 2%[5]. In contrast, nivolumab-induced gastritis is a less known adverse event.

An electronic search of the literature on nivolumab-induced gastritis was performed. Articles available in the PubMed, Medline, Cochrane, and Web of Science databases were reviewed up to December 1, 2022. The search terms used were “ICI-induced gastritis”, “nivolumab-induced gastritis”, “nivolumab and gastritis”. No time restrictions were used for the publications. A total of 30 articles and abstracts met the initial search criteria. The inclusion criteria were: Well-documented full-text articles written in English. We analysed a total of 19 case reports, which are summarised in Table 2.

In patients with nivolumab-induced gastritis, the most often reported symptoms include nausea, pain, diarrhea, loss of appetite, and weight loss[2-8]. Less commonly seen symptoms are hematemesis and dysphagia[9,10]. The onset of symptoms after the initiation of treatment varies considerably between a few weeks and 32 mo. In our case, the patient had diarrhea, nausea, epigastric discomfort, loss of appetite and mild weight loss – symptoms similar to other reported cases of nivolumab-induced gastritis. However, in our case, the symptoms manifested later than in most other cases – after 64 courses of nivolumab or, approximately, after 21 mo.

There are few case reports that provide the radiological findings, but the ones that do, show uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose in the stomach wall in positron emission tomography/CT scans[8,10-12]. Some of the published cases displayed stomach wall thickening seen in CT scans[5,13], as seen in our case, while others reported no significant findings on this investigation[3,14-16]. Thus, the importance of the CT scan in diagnosing nivolumab-induced gastritis is not yet clear.

EGD and multiple biopsies play one of the most significant roles in the diagnostic process of ICI-induced gastritis. In most instances, EGD findings show erythema[2-5,7,8,10,13,16,17,18,19], friable mucosa[3,5,7,16,19], erosions[2,7,8,17,20], and white fibrin-like exudate on the mucosa[7-10,13-16]. These endoscopic changes were also observed in our patient.

Due to the rarity of ICI-induced gastritis, there are currently few recommendations on how to treat this irAE. Brahmer et al[19] advised treating this form of gastritis with corticosteroids and reserve tumour necrosis factor-α blockers for cases resistant to steroids (suggestions based on previous case studies). In most of the reviewed cases, patients received corticosteroids (17 out of 19 cases), most of which improved their symptoms. However, in our case, the nivolumab-induced gastritis was not managed with steroids. Instead, the patient was successfully treated with three courses of omeprazole monotherapy and remains in remission. PPIs were used alone or in combination with other therapies in 9 of the 19 cases we reviewed. One of the more commonly used PPIs was pantoprazole[4,5,7,8]. In some of the cases that reported improvement in symptoms, PPIs were used in combination with other medications, namely – prednisone, methylprednisolone[4,7,8,10,12,21] or infliximab[2,8].

Shi et al[3] reported that treatment with pantoprazole and ranitidine gave desirable results only after cessation of nivolumab. Similar results were observed in a case report by Martínez-Acitores de la Mata et al[16]; remission was achieved after PPI therapy and cessation of nivolumab. Overall, in 9 of the 19 reviewed cases, ICI-induced gastritis was managed in part by discontinuing nivolumab therapy. In our case, nivolumab was not terminated because the patient did not have significant gastroenterological symptoms after treatment and the benefit of tumour suppression outweighed the risk of associated irAE.

In recent years, ICIs have become an option for the treatment of various types of cancer, but not much is known about biomarkers that predict adverse immune reactions. To date, none of the suggested biomarkers have demonstrated sufficient precision in predicting or signaling irAEs to be useful in clinical practise and more high-quality studies are needed to establish a balance between the antitumour effects of ICI therapy and the irAEs it causes[22,23].

ICI-induced gastritis, as a complication of immunotherapy, is much less common among clinicians and, consequently, much less known. As immunotherapy evolves and becomes more widely used, the probability of irAEs, including ICI-induced gastritis, will grow. When assessing a patient on immunotherapy presenting with symptoms of upper gastrointestinal tract distress, this diagnosis should be taken into account to provide the patient with timely intervention. Controlled clinical trials are needed to establish guidelines for the management of ICI-induced gastritis.

We would like to thank the patient and Vilnius University Hospital Santaros Clinics for giving us consent and providing the data to report this case.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Lithuania

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Paparoupa M, Germany; Rizzo A, Italy S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Ramos-Casals M, Brahmer JR, Callahan MK, Flores-Chávez A, Keegan N, Khamashta MA, Lambotte O, Mariette X, Prat A, Suárez-Almazor ME. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 880] [Article Influence: 176.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Johncilla M, Grover S, Zhang X, Jain D, Srivastava A. Morphological spectrum of immune check-point inhibitor therapy-associated gastritis. Histopathology. 2020;76:531-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shi Y, Lin P, Ho EY, Nock CJ. Nivolumab-associated nausea and vomiting as an immune adverse event. Eur J Cancer. 2017;84:367-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Placke JM, Rawitzer J, Reis H, Rashidi-Alavijeh J, Livingstone E, Ugurel S, Hadaschik E, Griewank K, Schmid KW, Schadendorf D, Roesch A, Zimmer L. Apoptotic Gastritis in Melanoma Patients Treated With PD-1-Based Immune Checkpoint Inhibition - Clinical and Histopathological Findings Including the Diagnostic Value of Anti-Caspase-3 Immunohistochemistry. Front Oncol. 2021;11:725549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Woodford R, Briscoe K, Tustin R, Jain A. Immunotherapy-related gastritis: Two case reports and literature review. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2021;15:11795549211028570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Alhatem A, Patel K, Eriksen B, Bukhari S, Liu C. Nivolumab-Induced Concomitant Severe Upper and Lower Gastrointestinal Immune-Related Adverse Effects. ACG Case Rep J. 2019;6:e00249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rovedatti L, Lenti MV, Vanoli A, Feltri M, De Grazia F, Di Sabatino A. Nivolumab-associated active neutrophilic gastritis. J Clin Pathol. 2020;73:605-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vindum HH, Agnholt JS, Nielsen AWM, Nielsen MB, Schmidt H. Severe steroid refractory gastritis induced by Nivolumab: A case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:1971-1978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kobayashi M, Yamaguchi O, Nagata K, Nonaka K, Ryozawa S. Acute hemorrhagic gastritis after nivolumab treatment. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:915-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Boike J, Dejulio T. Severe Esophagitis and Gastritis from Nivolumab Therapy. ACG Case Rep J. 2017;4:e57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tomiyasu H, Komori T, Ishida Y, Otsuka A, Kabashima K. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis in a melanoma patient treated with nivolumab. J Dermatol. 2021;48:E486-E487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cǎlugǎreanu A, Rompteaux P, Bohelay G, Goldfarb L, Barrau V, Cucherousset N, Heidelberger V, Nault JC, Ziol M, Caux F, Maubec E. Late onset of nivolumab-induced severe gastroduodenitis and cholangitis in a patient with stage IV melanoma. Immunotherapy. 2019;11:1005-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ebisutani N, Tozawa K, Matsuda I, Nakamura K, Tamura A, Hara K, Kondo T, Terada T, Tomita T, Oshima T, Fukui H, Hirota S, Miwa H. A Case of Severe Acute Gastritis as an Immune-Related Adverse Event After Nivolumab Treatment: Endoscopic and Pathological Findings in Nivolumab-Related Gastritis. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:2461-2465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bazarbashi AN, Dolan RD, Yang J, Perencevich ML. Combination Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Hemorrhagic Gastritis. ACG Case Rep J. 2020;7:e00402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mubder M, Bach L, Varshney N, Banerjee B. Nivolumab Induced Autoimmune Like Gastritis: A case report. Am J Biomed Sci Res. 2020;9. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Martínez-Acitores de la Mata D, Busto-Bea V, Cerezo-Aguirre C. Nivolumab-induced gastritis in a patient with metastatic melanoma. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). 2021;86:90-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhang ML, Neyaz A, Patil D, Chen J, Dougan M, Deshpande V. Immune-related adverse events in the gastrointestinal tract: diagnostic utility of upper gastrointestinal biopsies. Histopathology. 2020;76:233-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ferrian S, Liu CC, McCaffrey EF, Kumar R, Nowicki TS, Dawson DW, Baranski A, Glaspy JA, Ribas A, Bendall SC, Angelo M. Multiplexed imaging reveals an IFN-γ-driven inflammatory state in nivolumab-associated gastritis. Cell Rep Med. 2021;2:100419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, Atkins MB, Brassil KJ, Caterino JM, Chau I, Ernstoff MS, Gardner JM, Ginex P, Hallmeyer S, Holter Chakrabarty J, Leighl NB, Mammen JS, McDermott DF, Naing A, Nastoupil LJ, Phillips T, Porter LD, Puzanov I, Reichner CA, Santomasso BD, Seigel C, Spira A, Suarez-Almazor ME, Wang Y, Weber JS, Wolchok JD, Thompson JA; National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1714-1768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2245] [Cited by in RCA: 2574] [Article Influence: 367.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tsuji A, Hiramatsu K, Namikawa S, Yamamoto A, Midori Y, Murata Y, Tanaka T, Nosaka T, Naito T, Takahashi K, Ofuji K, Matsuda H, Ohtani M, Imamura Y, Iino S, Hasegawa M, Nakamoto Y. A rare case of eosinophilic gastritis induced by nivolumab therapy for metastatic melanoma. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2022;15:876-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Samonis G, Bousmpoukea A, Molfeta A, Kalkinis AD, Petraki K, Koutserimpas C, Bafaloukos D. Severe Gastritis Due to Nivolumab Treatment of a Metastatic Melanoma Patient. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Viscardi G, Tralongo AC, Massari F, Lambertini M, Mollica V, Rizzo A, Comito F, Di Liello R, Alfieri S, Imbimbo M, Della Corte CM, Morgillo F, Simeon V, Lo Russo G, Proto C, Prelaj A, De Toma A, Galli G, Signorelli D, Ciardiello F, Remon J, Chaput N, Besse B, de Braud F, Garassino MC, Torri V, Cinquini M, Ferrara R. Comparative assessment of early mortality risk upon immune checkpoint inhibitors alone or in combination with other agents across solid malignancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2022;177:175-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 42.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hommes JW, Verheijden RJ, Suijkerbuijk KPM, Hamann D. Biomarkers of Checkpoint Inhibitor Induced Immune-Related Adverse Events-A Comprehensive Review. Front Oncol. 2021;10:585311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |