Published online Jun 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i17.4117

Peer-review started: March 13, 2023

First decision: March 24, 2023

Revised: May 2, 2023

Accepted: May 19, 2023

Article in press: May 19, 2023

Published online: June 16, 2023

Processing time: 90 Days and 16.1 Hours

Penetrating arrow injuries of the head and neck are exceedingly rare in pediatric patients. This pathology has high morbidity and mortality because of the presence of vital organs, the airway, and large vessels. Therefore, the treatment and removal of an arrow is a challenge that requires multidisciplinary management.

A 13-year-old boy was brought to the emergency room after an arrow injury to the frontal region. The arrowhead was lodged in the oropharynx. Imaging studies showed a lesion of the paranasal sinuses without compromising vital structures. The arrow was successfully removed by retrograde nasoendoscopy without complications, and the patient was discharged.

Although rare, maxillofacial arrow injuries have high morbidity and mortality and require multidisciplinary management to preserve function and aesthetics.

Core Tip: Penetrating maxillofacial trauma is a rare, life-threatening pathology. Managing injuries caused by arrows is challenging because their removal can cause greater damage; therefore, the approach and treatment must be multidisciplinary. We present a pediatric patient who suffered a penetrating arrow injury of the frontal region without affecting vital structures and with successful removal.

- Citation: Rodríguez-Ramos A, Zapata-Castilleja CA, Treviño-González JL, Palacios-Saucedo GC, Sánchez-Cortés RG, Hinojosa-Amaya LG, Nieto-Sanjuanero A, de la O-Cavazos M. Frontal penetrating arrow injury: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(17): 4117-4122

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i17/4117.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i17.4117

Penetrating maxillofacial trauma caused by sharp objects, such as arrows, is infrequent but has high immediate morbidity and mortality[1]. Its incidence in the pediatric population is unknown; therefore, no standardized management exists[2]. Since this area has vital organs and large blood vessels, the approach and management must be immediate and multidisciplinary since extraction of the object can cause greater damage than the original trauma[3]. We report the case of a 13-year-old pediatric patient who suffered a frontal penetrating arrow injury with the tip lodged in the oropharynx without causing adjacent lesions. It was retrogradely removed by nasoendoscopy with excellent recovery.

A 13-year-old male adolescent came to the emergency room 30 min after a penetrating arrow lesion of the frontal region.

Thirty minutes before arriving at the emergency service, he was in an archery field practicing this sport. Another athlete accidentally shot him in the frontal region with an arrow. The blow caused him to fall. He had mild epistaxis without loss of consciousness or other neurological symptoms.

The patient had no history of other diseases.

The patient had no relevant family history.

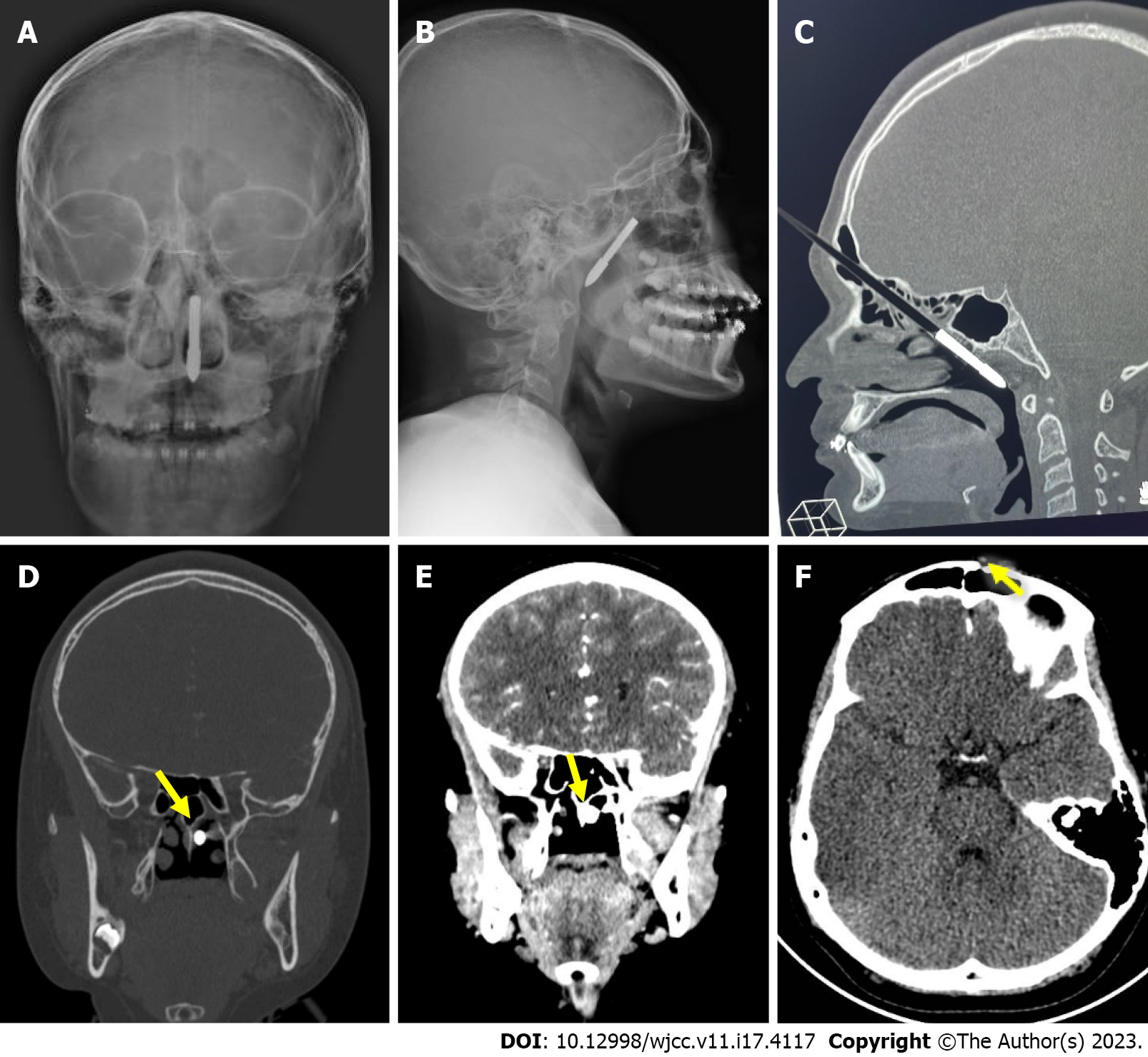

The patient weighed 60 kg, and his height was 160 cm. His heart rate was 85 beats per min, and his respiratory rate 18 breaths per min with a blood pressure of 110/80 mmHg and a temperature of 36.5 ºC. He was conscious with a cylindrical foreign body (arrow) 0.8 mm in diameter perpendicular to the plane of the forehead. The entry site was in the left frontal region, 1 cm from the supraciliary region, and 2 cm from the midline (Figure 1). There was no bleeding at the entry site and no neurological alterations.

A complete blood count, coagulation, and other laboratory tests were normal. PCR was performed for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) due to the epidemiological crisis. The result was negative.

Skull X-rays showed an arrow-shaped foreign body in the left frontal region penetrating the posterior pharynx through the ethmoid cells (Figure 2). A simple cranial computerized tomography (CT) scan confirmed the arrow´s inferior oblique path through the anterior and posterior ethmoid cells with the distal end in the nasopharynx in contact with the mucosa without a septal fracture. Other structures were not affected. In addition, a cranial angio-CT requested by the Neurosurgery Department did not show vascular lesions (Figure 2).

Only the remains of blood were seen in the rhinoscopy of the left nostril in the otorhinolaryngology evaluation. A metal foreign object was seen by rigid nasoendoscopy lodged obliquely in the left nasopharynx at the level of the choana, causing a non-penetrating wound without active bleeding.

Frontal penetrating arrow injury without vital structure lesions.

The foreign body was extracted 24 h after the accident by endoscopy. A 0º rigid endoscope was introduced through the right nostril up to the choana. The tip of the foreign body was seen medial to the middle and superior turbinates. It was retrogradely removed. The endoscope was reintroduced, and no evidence of active bleeding or lesions was found. The area was irrigated with ceftriaxone through a feeding tube, and a simple suture was placed in the frontal region.

The patient was monitored and managed with ceftriaxone during the postoperative period. His evolution was favorable. A follow-up cranial CT, the day after surgery, showed a fracture of the external wall of the left frontal bone that was treated conservatively with no further action (Figure 2). The patient was discharged on the fifth hospital day with no complications.

The main cause of injury and death in the pediatric population is trauma. Head trauma is most common, and maxillofacial trauma to a lesser extent[4]. Facial trauma includes soft, neurovascular, and bony tissue lesions of the eyes, nose, mouth, paranasal sinuses, teeth, and neck[1]. There are few reports of a penetrating wound in the maxillofacial region caused by arrows similar to the case reported herein. These lesions are more common in developing countries due to using these weapons in community conflicts[5]. In a study conducted in Nigeria to determine the prevalence of this type of maxillofacial trauma, four patients with penetrating injuries in the maxillofacial region by arrows were reported from January 1998 to December 2002[6]. This finding highlights the small number of patients described with this type of injury, which is even less frequent in pediatric patients. Most publications on penetrating injuries correspond to objects such as bullets, broken glass, or pieces of wood[6,7].

Arrows are low-velocity injuries that can be life-threatening when they affect vital organs and potentially devastating and fatal in head and neck injuries, depending on the distance the arrow is fired and the degree of penetration. The arrow can penetrate and injure a main blood vessel, causing hemorrhage, bruising, or laryngeal or tracheal lesions. In addition, it can manifest as respiratory distress due to obstruction requiring invasive airway management. If a brain or spinal cord injury occurs, the patient may present paraplegia, quadriplegia, hemorrhage, or death[1]. In our case, the arrow penetrated the frontal region, passing through the ethmoid sinuses until it reached the posterior wall of the pharynx without causing injury to vital structures.

This type of lesion in the maxillofacial region must be approached meticulously and systematically. Depending on the location of the injury, it may require multidisciplinary management that includes ophthalmology, otorhinolaryngology, neurosurgery, and maxillofacial surgery, among others[8]. The case reported herein was managed by the pediatric and otorhinolaryngology services and evaluated by the neurosurgery service. An otorhinolaryngologist extracted the foreign body.

Detailed knowledge of anatomy is one of the most important points in assessing penetrating maxillofacial injuries since the risk and expected complications depend on the location[9]. Penetrating head and neck injuries can affect three areas. The first is from the sternal notch to the cricoid cartilage. This area has the highest mortality due to the substantial risk of blood vessel injury and airway compromise[10]. The second extends from the cricoid cartilage to the mandibular angle. The most frequently injured structures here are the carotid arteries, the vertebral arteries, the jugular veins, the trachea, the larynx, and the esophagus. Penetrating injuries are more common in this region but with lower mortality than in Area 1 due to easier hemorrhage control[7]. The third area extends from the mandible angle to the base of the skull, involving the eyes, the distal carotid artery, the salivary glands, the pharynx, and the spinal cord[7,4]. The lesion occurred in the third area in our patient affecting the paranasal sinuses without involving any vital structure, so the prognosis was good.

A two-angle X-ray can be taken when there is clinical evidence or suspicion of a retained foreign body in this region to locate the object and define its relationship with vital structures. If the patient is hemodynamically unstable or has airway compromise, advanced life support must be provided. The airway, breathing, and circulation must be stabilized to continue with foreign body management[11]. This support was not required in this case, and imaging studies were directly conducted to locate the foreign body.

A CT scan is usually the study of choice to document the exact location and detail the penetrating foreign body and any associated injuries, especially in hemodynamically stable patients at the time of arrival to the emergency room. Subsequently, tomographic angiography can be performed to visualize suspected vascular damage if it is available[4,6,12]. A skull X-ray was initially performed on our patient. This study showed the arrow´s path through the paranasal sinuses to the pharynx. This path was later confirmed and determined in detail with tomography. A vascular lesion was ruled out by angio-CT.

Penetrating arrows in the head and neck region should be surgically removed considering tissue dissection, minimal hemorrhage, prevention of further injury, preservation of vital structures, wound irrigation, and drain placement according to depth[2,13]. The extraction route (retrograde or antegrade) depends on penetration, its relationship with vital structures, and the shape of the arrow[1,14]. A retrograde extraction was performed because it was easier to remove the arrow since it did not cause injuries to other structures during its trajectory. The otorhinolaryngology service mobilized the tip of the arrow by flexible nasoendoscopy and performed extraction without complications or sequelae.

The prognosis depends on the location of the foreign body, associated injuries, and timely multi

Recreational archery is a safe sport, even more than other popular sports such as soccer or baseball[15]. Among the most frequent injuries in archery are those related to wear or overuse of the hands and arms. Penetrating arrow injuries are rare due to the recommended protective equipment and safety protocols followed by each establishment[15]. Therefore, it is important to emphasize that the injury in our patient was preventable. It could have been avoided by properly following the safety protocols for shooting arrows. Fortunately, due to the path and location of the arrow, the patient had no complications or sequelae.

Penetrating head and neck injuries are rare in developed countries; however, medical personnel must be trained to manage this type of emergency. When caring for a patient with these characteristics, the main thing is to determine hemodynamic stability and later address the lesions caused by the foreign body and its trajectory to determine, together with other medical specialties, the best extraction route to minimize complications and sequelae. It is important to inform and educate parents on how to avoid these accidents.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country/Territory of origin: Mexico

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Oley MH, Indonesia; Tajiri K, Japan S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Adamu A, Ngamdu YB. Management of Penetrating Arrow Neck Injury: A Report of Two Cases. MAMC J Med Sci. 2020;6:63-67. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Abdullahi H, Adamu A, Hasheem MG. Penetrating Arrow Injuries of the Head-and-Neck Region: Case Series and Review of Literature. Niger Med J. 2020;61:276-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Melo MN, Pantoja LN, de Vasconcellos SJ, Sarmento VA, Queiroz CS. Traumatic Foreign Body into the Face: Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Dent. 2017;2017:3487386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saito N, Hito R, Burke P, Sakai O. Imaging of Penetrating Injuries of the Head and Neck: Current Practice at a Level 1 Trauma Center in the United States. Keio J Med 2014; 63: 23-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aremu SK, Dike B. Penetrated arrow shot injury in anterior neck. Int J Biomed Sci. 2011;7:77-80. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ismail A, Ismail N, Ali A, Mayoka R, Gingo W, Gebreegziabher F. Penetrating injury with an arrow impacted in the neck in rural Tanzania, a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;94:107133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Olasoji HO, Tahir AA, Ahidjo A, Madziga A. Penetrating arrow injuries of the maxillofacial region. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43:329-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mutabagani KH, Beaver BL, Cooney DR, Besner GE. Penetrating neck trauma in children: a reappraisal. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:341-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Holmgren E, Schartz D, Ramesh NP, Sylvester K, Eskey C. Penetrating Midface Trauma: A Case Report, Review of the Literature, and a Diagnostic and Management Protocol. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;79:430.e1-430.e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Brywczynski JJ, Barrett TW, Lyon JA, Cotton BA. Management of penetrating neck injury in the emergency department: a structured literature review. Emerg Med J. 2008;25:711-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Venkatachalapath TS. An interesting case of penetrating injury neck and face. Acta Med Iran. 2013;51:199-200. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Madsen AS, Kong VY, Oosthuizen GV, Bruce JL, Laing GL, Clarke DL. Computed Tomography Angiography is the Definitive Vascular Imaging Modality for Penetrating Neck Injury: A South African Experience. Scand J Surg. 2018;107:23-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Madhok BM, Roy DD, Yeluri S. Penetrating arrow injuries in Western India. Injury. 2005;36:1045-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bagheri SC, Khan HA, Bell RB. Penetrating neck injuries. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2008;20:393-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Palsbo SE. Epidemiology of recreational archery injuries: implications for archery ranges and injury prevention. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2012;52:293-299. [PubMed] |