Published online Jun 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i17.4090

Peer-review started: March 9, 2023

First decision: April 10, 2023

Revised: April 25, 2023

Accepted: May 19, 2023

Article in press: May 19, 2023

Published online: June 16, 2023

Processing time: 93 Days and 1.8 Hours

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a severe hyperinflammatory reaction, which is rare and life-threatening. According to the pathogen, HLH is divided into genetic and acquired. The most common form of acquired HLH is infection-associated HLH, of which Herpes viruses, particularly Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), are the leading infectious triggers. However, it is difficult to distinguish between simple infection with EBV and EBV-induced infection-associated HLH since both can destroy the whole-body system, particularly the liver, thereby increasing the difficulty of diagnosis and treatment.

This paper elaborates a case about EBV-induced infection-associated HLH and acute liver injury, aiming to propose clinical guides for the early detection and treatment of patients with EBV-induced infection-associated HLH. The patient was categorized as acquired hemophagocytic syndrome in adults. After the ganciclovir antiviral treatment combined with meropenem antibacterial therapy and methylprednisolone inhibition to inflammatory response, gamma globulin enhanced immunotherapy, the patient recovered.

From the diagnosis and treatment of this patient, attention should be paid to routine EBV detection and a further comprehensive understanding of the disease as well as early recognition and early initiation are keys to patients’ survival.

Core Tip: Most Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection resolves spontaneous complications. We report a unique case of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) complicating EBV infection and acute liver injury. EBV-associated acute liver injury is rare, occurs in children and young adults usually, and has conservative management. It is equivocal in distinguishing simple infection with EBV and EBV-induced infection-associated HLH. The doctor only cares about the symptoms of his/her personal clinical experience and ignores the detection of the EBV, thus, the optimal treatment miss. It is appropriate to comprehend the nature of the malady, searching for the primary cause of the disease in treatment.

- Citation: Sun FY, Ouyang BQ, Li XX, Zhang T, Feng WT, Han YG. Epstein-Barr virus-induced infection-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with acute liver injury: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(17): 4090-4097

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i17/4090.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i17.4090

According to the guidelines of Chinese medical doctor association, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) can be divided into familial and acquired. Primary HLH mainly appears during childhood and adult HLH is rarely considered primary HLH[1]. The patient was diagnosed as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-induced infection-associated HLH. EBV, are the leading infectious triggers particularly, which can result in the acute liver injury. It is inevitable that EBV destroy the whole functional organs in a quick speed, so that it is too late to protect the other preserved body parts. In this case, the successful treatment of the patient can be because of the early diagnosis and timely standardized treatment in the early stage of the disease. In a word, the tips of preventing the diseases are early detection and normative treatment as soon as possible.

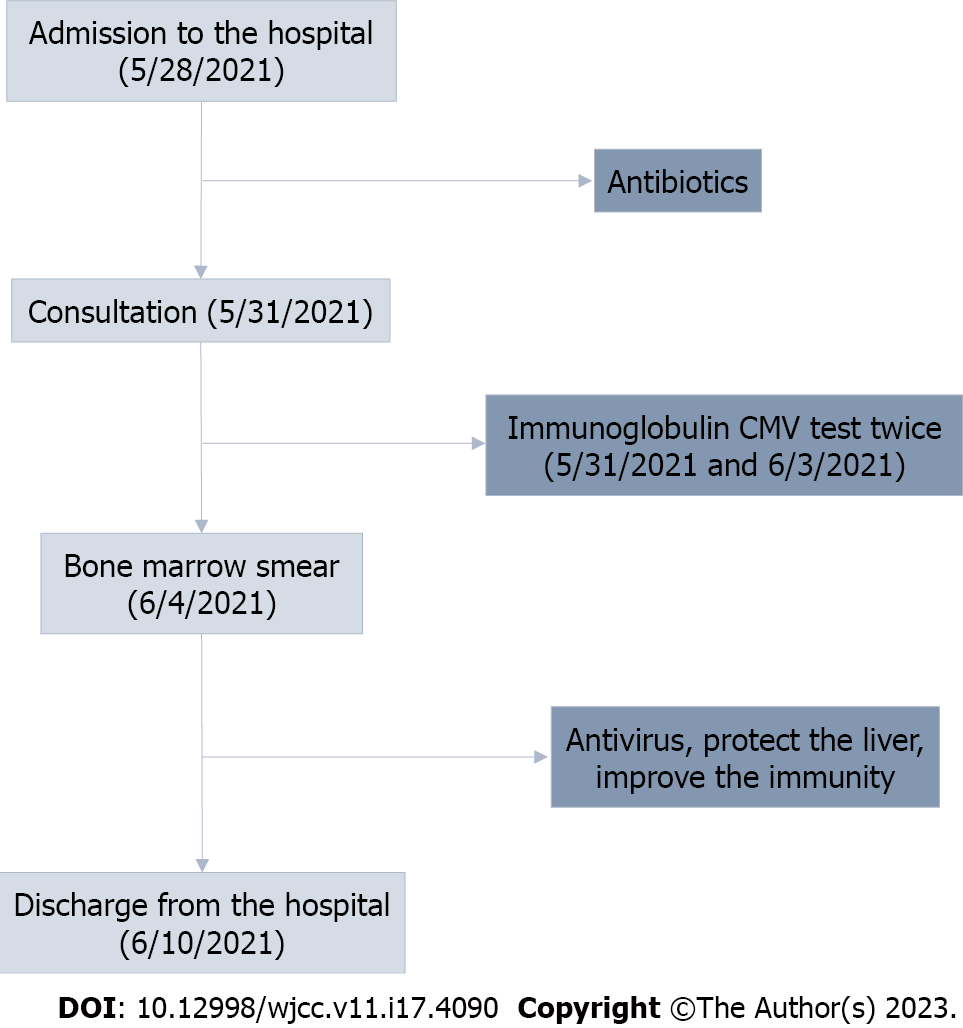

A 66-year-old woman with a 2-d history of weakness and poor appetite without a known etiology and a 1-d history of headache, dizziness, and fever presented to Seventh People’ s Hospital of Shanghai on May 28, 2021. At home, her body temperature was 40 °C, with no other associated symptoms. However, her symptoms were not alleviated despite rest (Figure 1).

Upon presenting to the emergency department, she was unconscious, sagging, hyperthermic (40 °C), had poor appetite, and was weak. Instant routine blood tests revealed the following results: White blood cell, 0.50 × 109/L; granulocyte%, 4.0%; lymphocyte%, 94.0%; C-reactive protein, 198.61 mg/L; and procalcitonin (PCT), 15.51 ng/mL. Pereion computed tomography (CT) revealed scattered fibrosis in both lung lobes, with consolidation on left lobe base. Abdominal CT revealed a fatty liver and a thickened appendix with coprolith. The patient was admitted and diagnosed with agranulocytosis after a discussion with the intensive care unit doctor. The patient was unconscious, lethargic, sagging, and weak had poor appetite, and was hyperthermic. Moreover, the amount of urine was within the normal range; however, stool unresolved since she had been admitted to the hospital.

The patient was previously well and was not using any specific drugs.

The patient had no history of associated diseases and had no drinking or smoking habits.

On physical examination, the patient was drowsy; sagging; with yellowish sclerae; and had left inguinal lymphoglandular swelling, with a hard texture, no tenderness, and no adhesion with neighboring tissues. The abdomen was soft, with no distention, no gastrointestinal movement or peristalsis, no varicosity, no tenderness, no rebound tenderness, no hypochondriac tenderness of the liver and spleen, no tenderness on both kidneys, no ureteral pain, had an accommodation reflex of three times/min, negative pathologic reflex, and positive physiologic reflex.

Test results revealed the following findings on admission: PCT, 16.47 ng/mL; complete blood cell indicated agranulocytosis; the liver function test revealed liver injury; and ultrasonography revealed left inguinal lymphoglandular swelling. Completing the hepatitis-related virus test and assaying the indicators of rheumatism as well as immunization, tumor, autoantibodies, and bone metabolism, the results were negative. However, further virus examination showed that the patient may be infected with a virus and bacteria; therefore, meropenem was initially used following consultation with our hospital antimicrobial management committee. We subsequently invited the professor of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University Infection Department for a consultation. The professor suggested including the detection of cytomegalovirus (CMV), immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgM, CMV DNA, and EB DNA (Table 1) and performing bone marrow aspiration (Figure 2). Peripheral blood smear was performed to determine whether or not a cytophagocytosis phenomenon existed. The abovementioned detections were completed, clearly suggesting an EBV infection (EB DNA, 2.83 × 104 IU/mL; CMV < 500 IU/mL which is below the lower limit). Following obtaining consent from the patient’s dependents, bone marrow aspiration was performed on June 4, 2021; the result was suggestive of an infection-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS). Therefore, this case was an example of EBV-induced infection-associated HLH with acute liver injury (Tables 1 and 2).

| Item | May 31 | Jun 3 |

| CMV-IgM (AU/mL) | 0.081 | CMV DNA: < 500 IU/mL |

| CMV-IgG (AU/mL) | > 1000 | |

| EBV-VCA-IgG (AU/mL) | 30.900 | EB virus DNA: 2.83 × 104 IU/mL |

| EBV-NA-IgG (AU/mL) | 6.790 | |

| EBV-EA-IgG (AU/mL) | 0.520 | |

| EBV-EA-IgA (AU/mL) | 0.070 | |

| EBV-EA-IgG (AU/mL) | 0.520 | |

| EBV-VCA-IgM (AU/mL) | 0.970 | |

| EBV-VCA-IgA (AU/mL) | 1.960 |

| Item | May 28 | June 1 | June 3 | June 10 |

| White blood cell (× 109/L) | 0.25 | 0.51 | 12.58 | 8.76 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 8.00 | 4.00 | 60.50 | 73.70 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 88.00 | 62.70 | 25.10 | 20.00 |

| Red blood cell (× 1012/L) | 4.48 | 3.93 | 4.23 | 4.14 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 126.00 | 109.00 | 117.00 | 117.00 |

| Platelet (× 109/L) | 121.00 | 163.00 | 195.00 | 173.00 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 164.96 | 69.17 | 46.26 | 1.55 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 16.47 | 1.94 | 0.86 | - |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 14.18 | - | 9.57 | - |

| IL-8 (pg/mL) | 90.13 | - | 43.15 | - |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 44.50 | 337.20 | 154.00 | - |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | - | 37.70 | 42.80 | - |

| γ-GT (U/L) | - | 221.00 | - | - |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 50.00 | 102.00 | 63.00 | 51.00 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 39.80 | 30.80 | 28.00 | 19.10 |

| Total bilirubin (umol/L) | 90.50 | 37.50 | - | 12.10 |

| Direct bilirubin (umol/L) | - | 15.10 | - | - |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 137.90 | - | 934.30 | - |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 1759.00 | > 2000 | - | - |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 5.08 | - | 4.89 | - |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 18.90 | 13.40 | 14.10 | 12.70 |

| Activated partial thromboplatin time (s) | 42.60 | 30.90 | 24.80 | 24.50 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 7.95 | 9.81 | 7.26 | 4.47 |

| D-Dimers (mg/L) | 1.69 | 1.83 | 2.07 | - |

| International normalized ratio | 1.51 | 1.10 | 1.15 | - |

| Total lymphocyte (M/L) | - | 320.00 | - | - |

| Total-T-lymphocyte (%) | - | 62.77 | - | - |

| Helper T cell CD4 (%) | - | 44.62 | - | - |

| Cytototoxic T cell CD8 (%) | - | 9.23 | - | - |

| CD4/CD8 ratio | - | 4.83 | - | - |

| Total lymphocyte B CD19 (%) | - | 28.70 | - | - |

| Natural killer cell (CD56 + CD16) (%) | - | 18.00 | - | - |

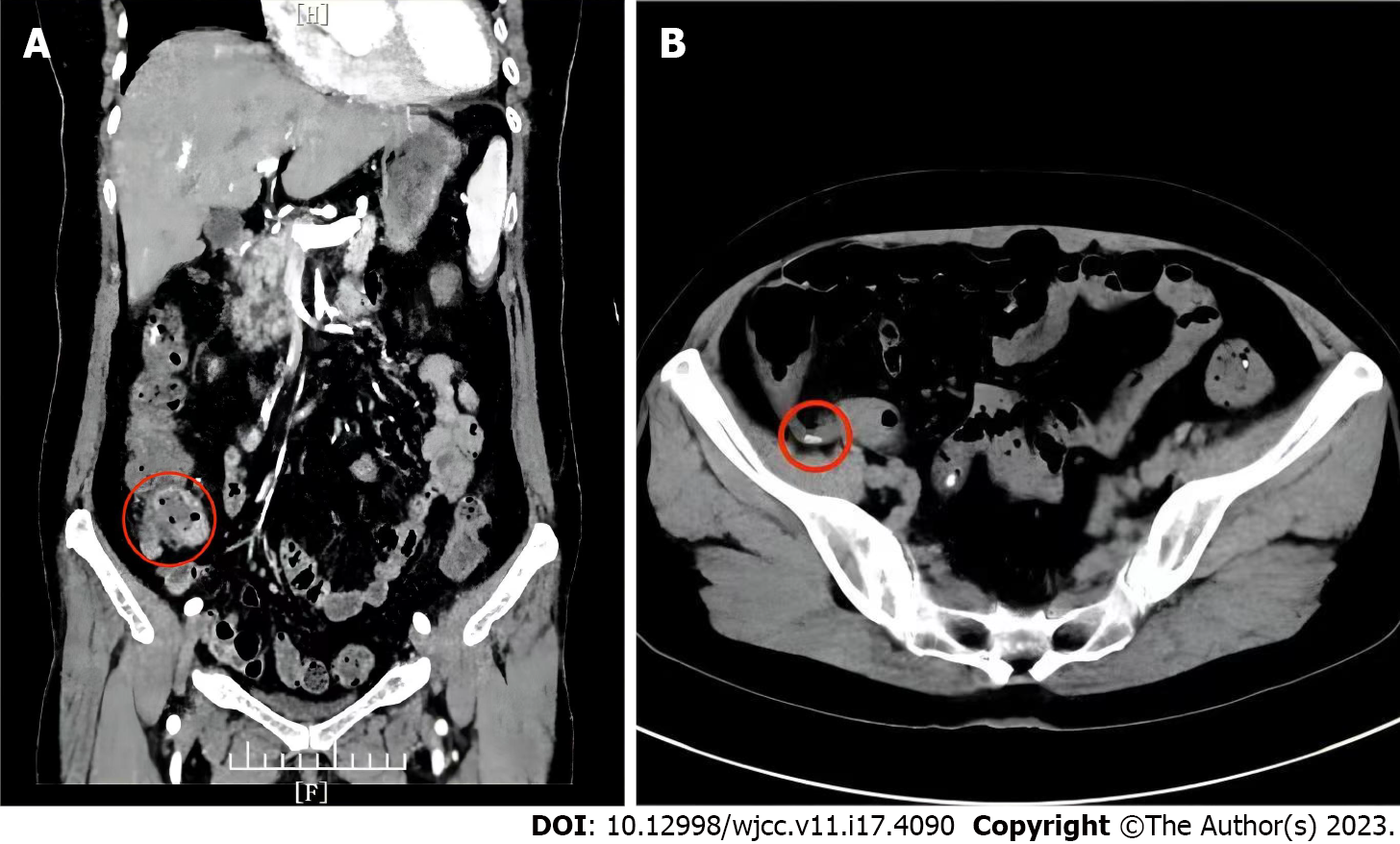

Ultrasonography was performed immediately after admission in the patients. Ultrasonic testing revealed the following findings: 1-2 hypoechoic groups subcutaneously in both inguinal areas, measuring approximately 11 mm × 6 mm on the left, regular morphology, clear boundary, clear cutaneous medullary demarcation, clear lymph node portal structure, and a small amount of blood flow signal. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography: (1) The local wall at the end of the ileum is thickened and the surrounding fat space is blurred with multiple small lymph nodes, suggestion: Inflammation may exist (Figure 3A); and (2) presence of appendiceal fecal stones (Figure 3B).

EBV-induced infection-associated HLH with acute liver injury.

Owing to agranulocytosis, we injected immunoglobulin intramuscularly 0.4 g/kg for 3 d, thereby enhancing immunizing power and lowering infection risk. We adjusted the medication regimen using acyclovir to fight the virus infection; recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and 2-(2-ethoxy-2-oxo-1-phenylethyl)-1,3-thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (Leucoson) to improve leukocyte formation; and γ-globulin to boost the immunity.

After a 5-d treatment of fighting infection, enhancing immunity, protecting the liver, and symptomatic supportive care, the WBC count increased to 12.58 × 109/L, and liver and coagulation function returned to the normal range. No discomforts were noted and her relevant indicators were within the normal range.

HPS is also known as HLH, with fever and splenomegaly as the main clinical manifestations. Laboratory determination of macrophages, methemoglobinemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, hypofibrinogenemia, spleen, lymph nodes, and bone marrow detected hemophilic cells[1]. Owing to the low rate of correct diagnosis and high mortality rate of HPS in the general population, clinicians lack understanding of the disease.

The first cases of HPS were reported in 1939[2]. According to the etiology, HPS can be divided into familial and acquired. Primary HPS mainly appears during childhood and adult HPS is rarely considered primary HPS. The patient in this report has no known genetic disease or family history; therefore, she was categorized as acquired HPS. In adults, the incidence of acquired HPS is approximately 1 in 800000 individuals[3]. The triggers of HPS in normal adults mainly include infection, tumor, and autoimmune disease[4]. Viral infections, including Herpes virus, particularly EBV and CMV infection, are the most common triggers[4-6]. This is followed by bacteria (mainly Mycobacterium tuberculosis), protozoa (mainly Leishmania), and fungi (Histoplasma)[7]. The most commonly associated malignancy with HPS development is lymphoma and HPS-associated autoimmune disorders include systemic lupus erythematosus and adult Still’ s disease[8].

The clinical manifestations of EBV-isolated infection and HPS caused by EBV infection are similar; however, we can differentiate them from their duration and severity. A simple EBV infection is mostly manifested as mild clinical symptoms, short disease course, and spontaneous recovery. In contrast, HPS caused by EBV infection tends to have progressive exacerbations, has multiple-organ involvement, and can lead to death. Liver injury has been reported as an independent risk factor for mortality[9].

The patient mainly presented with fever and agranulocytosis with a decline in neutrophil proportion and increasing lymphocytes, suggesting viral infection. The PCT level increased and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was within the normal range, suggesting bacterial infection. Therefore, we performed further assaying on the virus, bacteria, and fungal-related infection indicators. Nevertheless, the patient’ s condition rapidly deteriorated, with a progressive decline in liver function, persistently low blood cell levels, and continuously decreasing albumin levels. We did not rule out HPS because the bone marrow smear showed easily noticeable phagocytes. As this patient met 5 of 8 criteria, according to the HLH diagnostic criteria formulated by the International Organization Cytology Association in 2004, a clear diagnosis of HPS was made.

On physical examination, the patient had lymphadenopathy; however, both excluded tumor lesions from lung and abdominal CTs. Therefore, a tumor-related disease was not considered. The results of the patient’s immune-related tests were negative; therefore, immune disorders can be excluded. Moreover, the patient was diagnosed with EBV infection, which improved following antiviral therapy, and the transaminase levels decreased with anti-infective therapy. Therefore, EBV infection-related HPS could be diagnosed. The patient had agranulocytosis and liver injury. According to the relevant medical history, symptoms, and auxiliary examinations, the possibility of liver injury caused by viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver injury, drug-induced liver injury, and autoimmune diseases was little. Therefore, we initially considered liver injury caused by EBV infection.

HPS treatment is divided into the following two aspects: First, induction and remission therapy, which is to primarily control excessive inflammatory symptoms; second, etiological treatment, which focuses on correcting underlying immune deficiencies and controlling the primary disorder[10]. In this case, following ganciclovir antiviral treatment combined with meropenem antibacterial therapy and methylprednisolone inhibition to inflammatory response, gamma globulin enhanced immunotherapy, granulocyte levels increased, transaminase levels decreased, and the symptoms were relieved. According to the medical history, the patient was vaccinated before getting sick, which may have caused post-vaccination immune abnormalities, resulting in the potential EBV virus turning into an infectious state. Through early standardized treatment, the body’s immunity returned to a balanced state.

From the diagnosis and treatment of this patient, attention should be paid to routine EBV detection. Furthermore, HPS-related indicators should be monitored timely to avoid misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis of EBV infection-associated HPS for patients with fever, unexplained agranulocytosis, and liver injury. In this case, the successful treatment of the patient can be because of the early diagnosis and timely standardized treatment in the early stage of the disease. Therefore, a further comprehensive understanding of the disease as well as early recognition and early initiation are keys to patients’ survival.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Allergy

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Aydin S, Turkey; Ghannam WM, Egypt S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Chinese medical doctor association hematologists branch, Chinese medical association hematology group of pediatrics branch, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis of Chinese experts union. The diagnosis and treatment guidelines of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Zhongguo Yixue Zazhi. 2022;102:1492-1499. |

| 3. | Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383:1503-1516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 788] [Cited by in RCA: 962] [Article Influence: 87.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mostaza-Fernández JL, Guerra Laso J, Carriedo Ule D, Ruiz de Morales JM. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with viral infections: Diagnostic challenges and therapeutic dilemmas. Rev Clin Esp (Barc). 2014;214:320-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rouphael NG, Talati NJ, Vaughan C, Cunningham K, Moreira R, Gould C. Infections associated with haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:814-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liu P, Pan X, Chen C, Niu T, Shuai X, Wang J, Chen X, Liu J, Guo Y, Xie L, Wu Y, Liu Y, Liu T. Nivolumab treatment of relapsed/refractory Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2020;135:826-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shi W, Jiao Y. Nontuberculous Mycobacterium infection complicated with Haemophagocytic syndrome: a case report and literature review. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xu L, Guo X, Guan H. Serious consequences of Epstein-Barr virus infection: Hemophagocytic lymphohistocytosis. Int J Lab Hematol. 2022;44:74-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bahabri S, Al Rikabi AC, Alshammari AO, Alturkestany SI. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection: case report and literature review. J Surg Case Rep. 2019;2019:rjy096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhou Y, Wang S, Weng XB. Clostridium subterminale infection in a patient with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and haemophagocytic syndrome: A case report and literature review. J Int Med Res. 2022;50:3000605221129558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |