Published online Jun 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i17.4065

Peer-review started: December 27, 2022

First decision: March 24, 2023

Revised: April 24, 2023

Accepted: May 19, 2023

Article in press: May 19, 2023

Published online: June 16, 2023

Processing time: 167 Days and 1.5 Hours

Cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) is rare but may result in uterine rupture during pregnancy or massive hemorrhage during abortion procedures. Awareness of this condition is increasing, and most patients with CSP are now diagnosed early and can be managed safely. However, some atypical patients are misdiagnosed, and their surgical risks are underestimated, increasing the risk of fatal hemorrhage.

A 27-year-old Asian woman visited our institution because of abnormal pregnancy, and she was diagnosed with a hydatidiform mole through trans-vaginal ultrasound (TVS). Under hysteroscopy, a large amount of placental tissue was found in the scar of the lower uterine segment, and a sudden massive hemorrhage occurred during the removal process. The bilateral internal iliac arteries were temporarily blocked under laparoscopy, and scar resection and repair were rapidly performed. She was discharged in good condition 5 d after the operation.

Although TVS is widely used in the diagnosis of CSP, delays in the diagnosis of atypical CSP remain. Surgical treatment following internal iliac artery temporary occlusion may be an appropriate management method for unanticipated massive hemorrhage during CSP surgery.

Core Tip: Unanticipated massive hemorrhage during cesarean scar pregnancy surgery can lead to serious complications. If not effectively managed, it can lead to hemorrhagic shock or even death. Uterine artery embolization is usually used to prevent massive hemorrhage, but it requires multidisciplinary cooperation and cannot be performed immediately in the case of emergency. We adopted bilateral internal iliac artery emergency temporary occlusion to control intraoperative bleeding immediately without postoperative complications, and this may be a feasible method.

- Citation: Xie JP, Chen LL, Lv W, Li W, Fang H, Zhu G. Emergency internal iliac artery temporary occlusion after massive hemorrhage during surgery of cesarean scar pregnancy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(17): 4065-4071

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i17/4065.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i17.4065

The term “cesarean scar pregnancy” (CSP) describes pregnancies that develop after the implantation of fertilized eggs, embryos, or gestational sacs at the site of a prior cesarean delivery scar[1]. CSP occurs in 4 percent of all pregnancies, with a reported frequency of 1/2216-1/1800[2,3]. Cesarean section (CS) rates have been rising over the world in recent years, and in China, the relaxation of the two-child policy may increase the additional risk of CSP in reproductive-aged women with a history of CS[4]. Delaying CSP therapy might result in major side effects such as bleeding, uterine rupture, hysterectomy, and possibly loss of fertility[5]. Thus, the standard management of CSP is the timely termination of pregnancy.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVS) is the most effective tool and first-line imaging modality for diagnosing CSP[6,7]; early diagnosis and prompt treatment are vital for reducing maternal mortality. Unfortunately, the research reports a shockingly high number of missed diagnoses of CSP, 107 (13.6%) of the 751 instances of CSP were overlooked or misdiagnosed, which increased morbidity[8]. Therefore, identifying methods to manage CSP in an emergency to reduce the occurrence of complications and protect the fertility of patients is crucial. In this paper, we report a case of a patient with CSP that was misdiagnosed by TVS as a hydatidiform mole who suffered massive hemorrhage during hysteroscopic surgery, underwent laparoscopic scar resection and repair after internal iliac artery temporary occlusion, and had a positive outcome. The Tongde Hospital’s Institutional Review Board verified that ethical approval of this retrospective study was exempt.

A 27-year-old Chinese woman presented to the outpatient department of our hospital with abnormal pregnancy.

The patient had experienced menopause for 60 d. Her normal menstrual cycle was 27-35 d, and a urine pregnancy test was positive at 40 d of menopause. After 52 d of menopause, 174.8 mIU/mL of blood beta human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) and 3.79 nmol/L of progesterone were examined in the hospital, and TVS indicated a honeycomb mixed echo in the uterine cavity of approximately 7.6 cm × 6.2 cm and a rich blood flow, some of which seemed to be embedded in the CS scar. The patient had no abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding and was experiencing a mild early pregnancy reaction. She was admitted to our hospital because of the abnormal pregnancy indicated by TVS.

The patient had been delivered by CS due to macrosomia 4 years previously.

The patient has no relevant family history.

The patient had a temperature of 36.7 °C, heart rate of 82 bpm, respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute, and blood pressure of 117/62 mmHg, and the oxygen saturation in room air was 99%. After admission, a gynecological examination revealed some bloody secretion in the vagina, mild cervical erosions without lifting pain, enlargement of the anterior uterus similar to that at 60 d of pregnancy without tenderness, and no abnormalities in the bilateral appendages.

Hemoglobin level was 126 g/L, blood β-hCG was 189.6 mIU/mL, progesterone was 1.0 nmol/L, and the white cell and platelet count were normal. The prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times were normal, and the d-dimer value was 1.98 mg/L. Serum C-reactive protein was normal. The blood biochemistry and urine analyses were normal.

According to the TVS review, the scar area revealed a disorderly high echo mass, and multiple vesicular echoes were found in utero, with the largest being approximately 2.2 cm × 1.1 cm (Figure 1). An embryo abortion was considered, and a hydatidiform mole could not be excluded. The electrocardiogram and chest computed tomography scan were also normal.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was unclear, with CSP, a hydatidiform mole, and spontaneous abortion all considered.

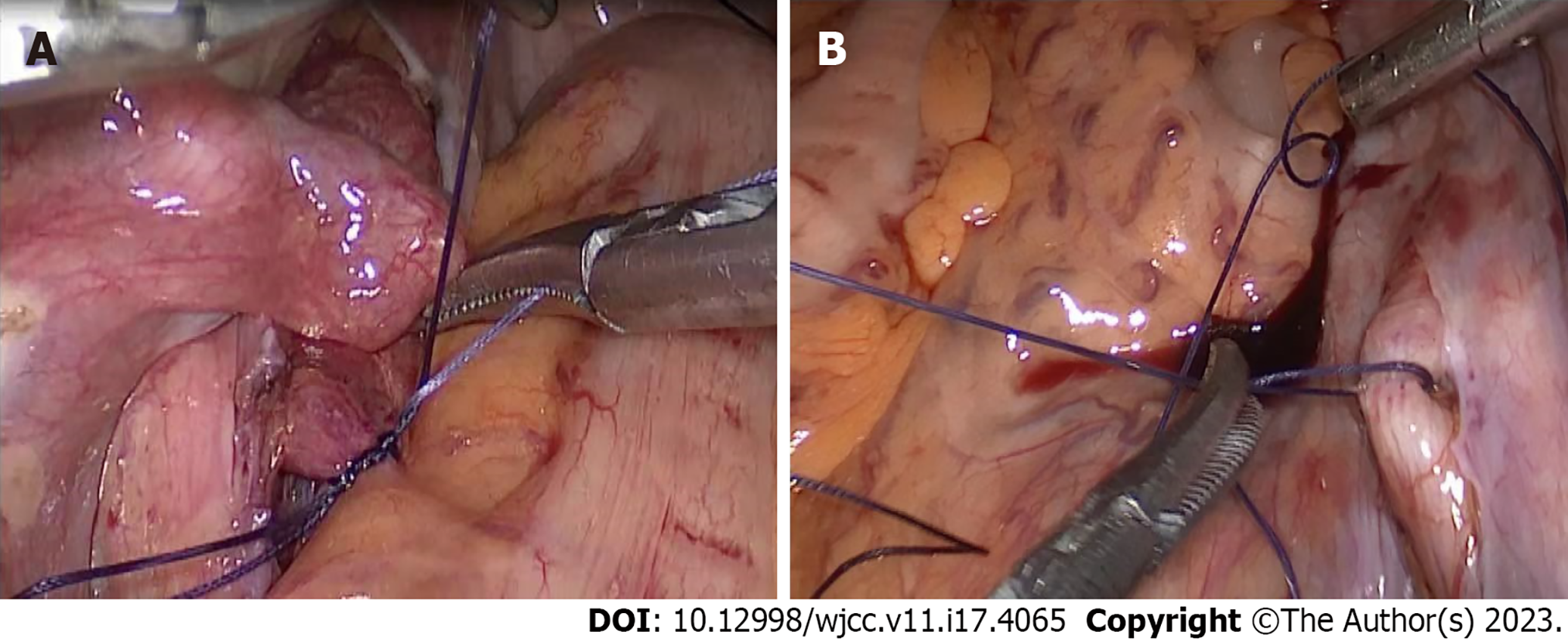

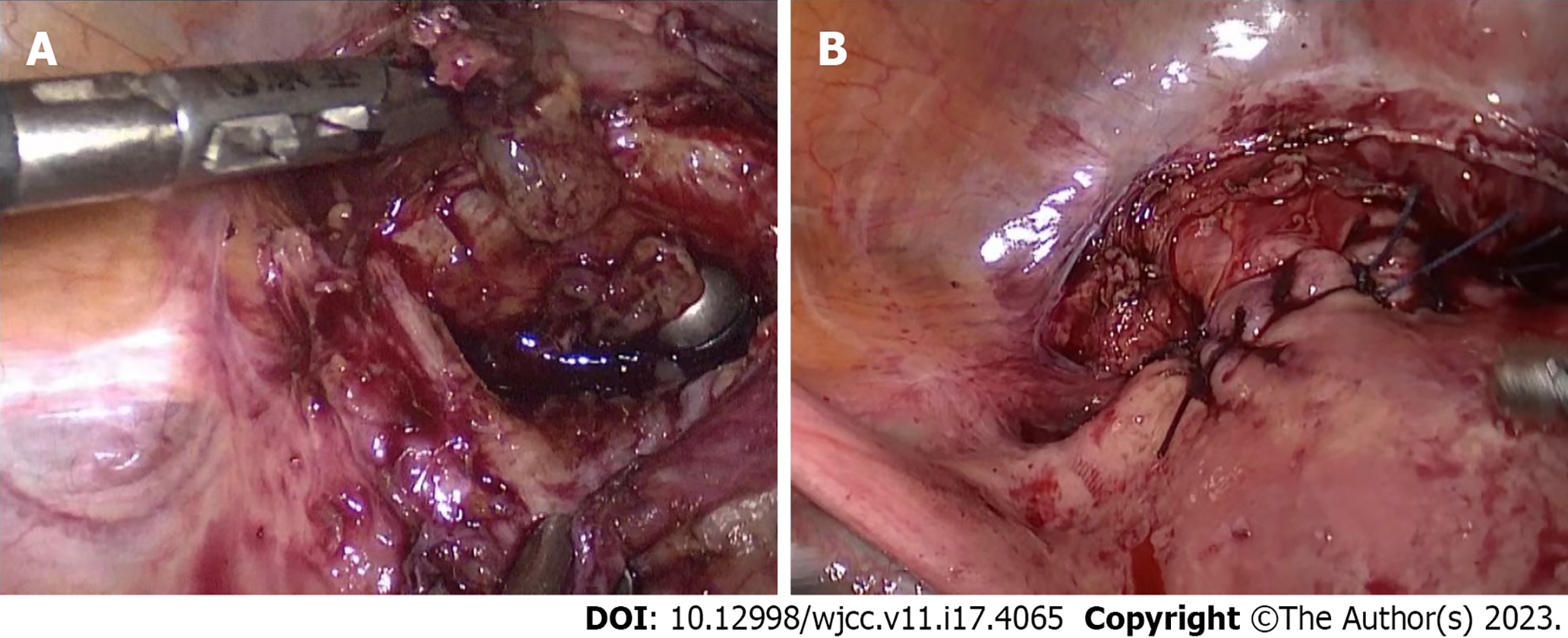

Hysteroscopic surgery with informed consent was planned for further diagnosis. Through hysteroscopy, we observed that a large amount of tissue with blood clots had adhered to the scar in the lower segment of the uterine cavity, and no obvious pregnancy sac or hydatidiform mole tissue was identified. When we clamped the scar tissue and blood clots, a large amount of blood flowed from the uterine cavity and was difficult to control. We used two vascular forceps to rapidly clamp the bilateral uterine arteries from the cervix and the cervix itself, thus reducing the bleeding, and laparoscopy was performed. During laparoscopic surgery, we observed that the uterus was enlarged to a size similar to 60 d after pregnancy. In addition, the lower scar was obviously enlarged, and the blood vessels on the surface were clearly dilated. The posterior peritoneum was opened and the bilateral internal iliac arteries dissociated. A no. 1 absorbable suture was used as a slipknot to temporarily stop the blood flow (Figure 2). The scar was then incised, pregnancy tissue removed, scar cutting edge trimmed, and uterine wall repaired (Figure 3). Finally, hysteroscopy was performed to examine the uterine cavity, with no pregnancy tissue being found or diverticula formed. To confirm that there was no obvious bleeding on the suture surface, the internal iliac artery was untied to restore blood flow. The uterine wound was checked for bleeding after the pelvic cavity was cleaned with warm saline and diluted iodophor. We stitched up the wound afterward. Our patient got two units of packed red blood cells throughout the procedure, and there were no acute issues despite an estimated intraoperative blood loss of 1000 mL.

Postoperatively, we used cefuroxime sodium to prevent infection, oral iron for erythropoiesis, and oxytocin to promote uterine contractions. We observed that the β-hCG was 35.2 mIU/mL on postoperative day 1, and 3 d following surgery, and the usual inflammatory signs progressively returned to normal levels. A routine blood examination suggested mild anemia and no obvious abnormalities in the blood biochemistry or coagulation function. On the first postoperative day, the patient anal exhaled, and on the third postoperative day, the patient defecated. During hospitalization, she experienced some vaginal bleeding but no symptoms such as abdominal pain, fever, thrombosis, or intestinal obstruction. The patient recovered well and was discharged on postoperative day 5.

Pathological report: Vestigial villi and decidual tissue were observed in the scar tissue of the uterus. During the follow-up assessment approximately 1 wk after discharge, the patient’s β-hCG levels had returned to normal (2.9 mIU/mL), and 1 mo after discharge, a vaginal three-dimensional ultrasound indicated that the blood supply to the uterus and ovaries was normal.

CSP is a rare and iatrogenic form of ectopic pregnancy that is considered a potentially life-threatening condition. It is crucial to diagnose problems quickly and treat them right away. An empty endometrial cavity and cervical canal, the presence of a gestational sac in the anterior uterine wall, and a strong trophoblastic/placental blood flow are all factors that aid in the diagnosis of CSP through transvaginal ultrasonography[9-11]. Studies have reported that the accuracy of TVS in diagnosing CSP is only 84.6%[2], with some misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis known to occur. The diagnosis accuracy of TVS depends on the pregnancy period. In continuing pregnancies, after 7 wk, the gestational sac migrates toward the fundus populating the uterine cavity. If the patient’s previous history of CS and scar site examination are ignored, clinicians are often misled into believing that it is a normal intrauterine pregnancy[6]; incomplete abortion with an intrauterine hematoma could also affect the doctor’s judgment of CSP, resulting in misdiagnosis. However, the inaccuracy of diagnosis directly affects the quality of the subsequent treatment, increasing the risk of hemorrhage and morbidity.

Our patient was misdiagnosed through TVS as having a hydatidiform mole, which may be related to abnormally high vascularities and varicosities in the anterior lower segment of the uterus. In addition, the low levels of β-hCG may explain why clinicians did not diagnose CSP, as β-hCG levels usually represent the activity of placental trophoblastic cells. However, studies have demonstrated that even at low levels of β-hCG, when the blood vessels are exposed after the pregnancy tissue has been cleared, contractions of the muscle layer cannot effectively stop bleeding in defects in the muscle layer at the scar site, leading to the occurrence of unpredicted catastrophic hemorrhage. Therefore, for patients with uterine scar, early ultrasound examination findings are key, even if the patient has a miscarriage or low β-hCG levels. However, this does not mean that the risk of surgery is low, as this case illustrates. Only by formulating a complete surgical program can the risk of severe postoperative complications be reduced.

The ideal therapy for CSP would include the safe removal of pregnant tissue, the repair of the uterine abnormality, and the maintenance of fertility. According to published reports, contemporary treatment options include medication, uterine artery embolization (UAE) in conjunction with hysteroscopic resection, dilatation and curettage, laparotomy, laparoscopy, and transvaginal resection[12]. UAE is suitable for patients with refractory CSP at high risk of massive hemorrhage and can be combined with all the aforementioned surgical methods to effectively prevent bleeding. Injury to the ovarian and urinary systems, as well as rectal perforation, sepsis, and pulmonary embolism, are all possible outcomes of UAE[13-16]. In addition, the operation requires interdisciplinary cooperation, primarily for preoperative planning, but it is difficult to quickly complete patient transport and preparation for interventional surgery when sudden massive bleeding is encountered.

The characteristic of this case is the occurrence of unpredicted vaginal hemorrhage during the operation. Under laparoscopy, the blood vessels on the surface of the scar were obviously dilated; if the scar had been removed, the uterine hemorrhage would have been aggravated. UAE may not be available in the case of emergency, and if it is performed, the type of non-predictable emergency operation required may result in postoperative complications. In addition, the patient was young and wanted her fertility to be preserved, which limited the plan for hysterectomy. In this case, through bilateral internal iliac artery temporary occlusion, the hemostatic effect during the operation was satisfactory, the residual pregnancy contents in utero were removed, and the uterine scar was repaired, which could improve the patient’s reproductive outcome. The method was simple and easy to operate, and blood supply was restored immediately after the removal of the blockage. No postoperative complications were noted, the postoperative hospital stay was shortened, and the medical expenses were reduced.

The earliest treatment of CSP after laparoscopic bilateral internal iliac artery ligation was reported in 2006[17]. By temporarily blocking off both internal iliac arteries, blood flow to the uterus may be reduced by 48%, and pulse pressure can be reduced by 85%[18], resulting in better control of bleeding than with UAE because of vascular anastomosis between the internal iliac artery and its three offshoots (the uterine artery, the vaginal artery, and the internal pudendal artery). According to a review of recent literature[12,19-21], bilateral internal iliac artery temporary occlusion seems to be an effective strategy for reducing bleeding during CSP treatment without causing massive bleeding; hysteroscopy is required to deal with intrauterine lesions. Because the internal iliac artery occlusion is temporary, no serious complications are observed (Table 1). This method is also suitable for acute intraoperative bleeding and is superior to UAE[20] and hysterectomy. However, it may have defects because a high level of surgical skill is required. In addition, few cases have been reported, and some complications may not have been detected. In order to confirm the efficacy and safety of this method, bigger sample size studies are necessary.

| Li et al[19], 2018 | Xu et al[12], 2019 | Zhao et al[20], 2022 | Su et al[21], 2022 | |

| Number of participants | 1 | 5 | 33 | 21 |

| CSP type | III | II | III | III |

| Age (yr) | 28 | 28-39 | 28.97 ± 4.61 | 34.38 ± 4.30 |

| Menelipsis time (d) | 77 | 45-60 | 48.51 ± 2.39 | 47.35 ± 12.73 |

| Blood β-hCG before operation (mIU/mL) | 40542 | 4569-67762 | 18906.12 ± 11296.74 | 2.62 ± 0.76 (10000 mol/L) |

| Operation time (min) | 85 | 60-165 | 126.47 ± 13.21 | Not described |

| Occlusion time (min) | 27 | 20-26 | Not described | 30 ± 12.05 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | Minimal | 20-40 | 112.44 ± 22.65 | 67.14 ± 32.78 |

| Blood transfusion | No | No | No | No |

| Decrease rate of serum β-hCG 24 h after surgery (%) | Not described | Not described | 81 ± 2.15 | Not described |

| Length of hospital stay (d) | 3 | 2-3 | 5.28 ± 1.21 | 5.14 ± 0.32 |

| Incidence of postoperative complications (%) | None | None | 6 ± 2.320 | None |

| Time to β-hCG normalization (wk) | Not described | 3-4 | Not described | Not described |

| Ovarian function 3-6 mo after surgery | Not described | Not described | Normal | Not described |

Although the misdiagnosis of CSP is rare, it can lead to serious complications, resulting in life-threatening hemorrhage. A safe and simple treatment is needed for accidental massive bleeding during CSP surgery, and bilateral internal iliac artery temporary occlusion may be a viable treatment option, but more cases and multicenter cohort studies are required to verify this conclusion.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fabbri N, Italy; Ghimire R, Nepal; Nagamine T, Japan; Tolunay HE, Turkey S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YX

| 1. | Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Cali G, El Refaey H, Kaelin Agten A, Arslan AA. Easy sonographic differential diagnosis between intrauterine pregnancy and cesarean delivery scar pregnancy in the early first trimester. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:225.e1-225.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rotas MA, Haberman S, Levgur M. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1373-1381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 400] [Cited by in RCA: 425] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Maymon R, Svirsky R, Smorgick N, Mendlovic S, Halperin R, Gilad K, Tovbin J. Fertility performance and obstetric outcomes among women with previous cesarean scar pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30:1179-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liang J, Mu Y, Li X, Tang W, Wang Y, Liu Z, Huang X, Scherpbier RW, Guo S, Li M, Dai L, Deng K, Deng C, Li Q, Kang L, Zhu J, Ronsmans C. Relaxation of the one child policy and trends in caesarean section rates and birth outcomes in China between 2012 and 2016: observational study of nearly seven million health facility births. BMJ. 2018;360:k817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Qian ZD, Weng Y, Du YJ, Wang CF, Huang LL. Management of persistent caesarean scar pregnancy after curettage treatment failure. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Calì G, D'Antonio F, Kaelin Agten A. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Diagnosis and Pathogenesis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2019;46:797-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shi L, Huang L, Liu L, Yang X, Yao D, Chen D, Xiong J, Duan J. Diagnostic value of transvaginal three-dimensional ultrasound combined with color Doppler ultrasound for early cesarean scar pregnancy. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:10486-10494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A. Unforeseen consequences of the increasing rate of cesarean deliveries: early placenta accreta and cesarean scar pregnancy. A review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:14-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 384] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tamada S, Masuyama H, Maki J, Eguchi T, Mitsui T, Eto E, Hayata K, Hiramatsu Y. Successful pregnancy located in a uterine cesarean scar: A case report. Case Rep Womens Health. 2017;14:8-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Seow KM, Huang LW, Lin YH, Lin MY, Tsai YL, Hwang JL. Cesarean scar pregnancy: issues in management. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:247-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 393] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nawroth F, Foth D, Wilhelm L, Schmidt T, Warm M, Römer T. Conservative treatment of ectopic pregnancy in a cesarean section scar with methotrexate: a case report. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;99:135-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xu W, Wang M, Li J, Lin X, Wu W, Yang J. Laparoscopic combined hysteroscopic management of cesarean scar pregnancy with temporary occlusion of bilateral internal iliac arteries: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e17161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Qiu J, Fu Y, Huang X, Shu L, Xu J, Lu W. Acute pulmonary embolism in a patient with cesarean scar pregnancy after receiving uterine artery embolization: a case report. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:117-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang Y, Huang X. Sepsis after uterine artery embolization-assisted termination of pregnancy with complete placenta previa: A case report. J Int Med Res. 2018;46:546-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mallick R, Okojie A, Ajala T. Rectal perforation: An unusual complication of uterine artery embolisation. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;36:867-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kaump GR, Spies JB. The impact of uterine artery embolization on ovarian function. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24:459-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kung FT, Huang TL, Chen CW, Cheng YF. Image in reproductive medicine. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1508-1509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Burchell RC. Physiology of internal iliac artery ligation. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1968;75:642-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li J, Li X, Yu H, Zhang X, Xu W, Yang J. Combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic management of cesarean scar pregnancy with temporary occlusion of bilateral internal iliac arteries: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhao Q, Sun XY, Ma SQ, Miao MW, Li GL, Wang JL, Guo RX, Li LX. Temporary Internal Iliac Artery Blockage versus Uterine Artery Embolization in Patients After Laparoscopic Pregnancy Tissue Removal Due to Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:501-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Su X, Yang M, Na Z, Wen C, Liu M, Cai C, Zhong Z, Zhou B, Tang X. Application of laparoscopic internal iliac artery temporary occlusion and uterine repair combined with hysteroscopic aspiration in type III cesarean scar pregnancy. Am J Transl Res. 2022;14:1737-1741. [PubMed] |