Published online Jun 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i16.3837

Peer-review started: February 9, 2023

First decision: March 28, 2023

Revised: April 2, 2023

Accepted: April 12, 2023

Article in press: April 12, 2023

Published online: June 6, 2023

Processing time: 112 Days and 13.8 Hours

Given its size and location, the liver is the third most injured organ by abdominal trauma. Thanks to recent advances, it is unanimously accepted that the non-operative management is the current mainstay of treatment for hemodynamically stable patients. However, those patients with hemodynamic instability that generally present with severe liver trauma associated with major vascular lesions will require surgical management. Moreover, an associated injury of the main bile ducts makes surgery compulsory even in the case of hemodynamic stability, thereby imposing therapeutic challenges in the tertiary referral hepato-bilio-pancreatic centers’ setting.

We present the case of a 38-year-old male patient with The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma grade V liver injury and an associated right branch of portal vein and common bile duct avulsion, due to a crush polytrauma. The patient was referred to the nearest emergency hospital and because of the hemorrhagic shock, damage control surgery was performed by means of ligation of the right portal vein branch and right hepatic artery, and hemostatic packing. Afterwards, the patient was referred immediately to our tertiary hepato-bilio-pancreatic center. We performed depacking, a right hepatectomy and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. On the 9th postoperative day, the patient developed a high output anastomotic bile leak that required a redo of the cholangiojejunostomy. The postoperative period was marked by a surgical incision site of incomplete evisceration that was managed non-operatively by negative wound pressure. The follow-up was optimal, with no complications at 55 mo.

In conclusion, the current case clearly supports that a favorable outcome in severe liver trauma with associated vascular and biliary injuries is achieved thru proper therapeutic management, conducted in a tertiary referral hepato-bilio-pancreatic center, where a stepwise and complex surgical approach is mandatory.

Core Tip: This paper analyzes a rare and difficult case of a 38-year-old male patient that presented to the nearest emergency hospital for polytrauma secondary to a crush injury, which mainly resulted in a severe liver trauma associated with vascular and biliary injury (grade V liver trauma with severe laceration involving more than 75% of the right hemiliver with injury of the right portal vein and common bile duct). Its management consisted in emergency damage control surgery for hemostasis by vascular ligation and packing in a primary trauma center. This was followed by a major liver resection (right hepatectomy) and biliary reconstruction in a tertiary hepato-bilio-pancreatic (HBP) center. The patient recovered well with no long-term complications and had a follow-up ultrasound that showed no issues. Currently, the overall survival is 55 mo. In conclusion, the current case clearly supports that a favorable outcome in severe liver trauma with associated vascular and biliary injuries is achieved thru proper therapeutic management, conducted in a tertiary referral HBP center, where stepwise and complex surgical approach is mandatory.

- Citation: Mitricof B, Kraft A, Anton F, Barcu A, Barzan D, Haiducu C, Brasoveanu V, Popescu I, Moldovan CA, Botea F. Severe liver trauma with complex portal and common bile duct avulsion: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(16): 3837-3846

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i16/3837.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i16.3837

The general term “liver trauma” covers blunt or penetrating abdominal trauma that causes parenchymal hepatic injury and could involve a wide spectrum of intra and/or extra-parenchymal vascular stru

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) classification, based on morphologic and imaging criteria, is scaled from I to VI, from the least injury to the most severe, and according to the anatomic disruption characteristics of the liver lesions. Grades from I to V are compatible with survival and represent increasingly complex injuries. Grade VI consists of a destructive lesion, usually incompatible with survival. This classification facilitates the comparison of an equivalent injury that is manageable by several therapeutic conducts[3]. The consecutive severity is based on the potential threat to the patient's life. In clinical practice, 80%-90% of the encountered liver lesions are minor and moderate[5]. Advances of the last decades have shifted the mainstay of treatment from exploratory laparotomy to non-operative management (NOM) by multidisciplinary teams in experienced centers[6,7].

The hemodynamic status, anatomic lesion, as well as associated injuries must be analyzed when deciding upon the optimal management plan[3]. NOM is the first choice of treatment in all hemodynamically stable patients with AAST grade I-V injuries, showing no sign of peritonitis or other lesions requiring surgery[8,9].

However, in clinical practice it is generally admitted that patients with severe liver trauma graded ≥ III who present hemodynamic instability after initial fluid resuscitation must undergo an emergency laparotomy aimed at prompt bleeding control[10]. Thus, hemodynamically unstable patients should undergo operative management (OM), with major resections only to be considered in subsequent surgical interventions, and not upon the primary surgery setting – that should solely control the hemorrhage and restrict the bile leak[3].

AAST grade V-VI injuries are associated with vascular avulsion and higher mortality rates[11]. Vascular avulsion secondary to trauma is very rare and represents a challenge for surgeons who need to perform damage control surgery and can include the ligation of the injured vessels[12]. Post-traumatic bile duct injuries represent another entity that poses a high risk to major complications such as choleperitoneum and biliary fistulas[10].

The computed tomography (CT) scan is the gold standard investigation for diagnosing post-traumatic abdominal lesions and has a key role in selecting the treatment strategy[13]. However, bile duct lesions pose great diagnostic issues in the post-traumatic setting; literature data suggest that the clinical diagnosis is extremely difficult and stand-alone CT scanning does not hold an adequate sensitivity for detecting biliary leaks[14]; moreover, high morbidity rates are related to a delayed diagnosis thereby making the early diagnosis crucial[10].

The existing literature offers few studies that report the association between severe liver trauma, right portal vein branch, and common bile duct avulsion, and therefore the present paper is aimed at filling the gaps of knowledge by presenting the management of such a challenging injury.

We present the case of a 38-year-old male patient who was taken to the nearest emergency room with polytrauma due to a crush injury which presented with hemorrhagic shock due to a grade V liver trauma with severe laceration involving more than 75% of the right hemiliver, avulsion of the right portal vein and common bile duct, with massive hemoperitoneum, right hemopneumothorax, pulmonary contusions, right renal hematoma, II-X rib fractures and a left clavicle fracture.

Emergency laparotomy was performed, consisting with ligation and suture of the right portal vein, intentional ligation of the right hepatic artery for hemostasis, drainage of the total biliary fistula (the biliary reconstruction was not considered at this time), and perihepatic packing. Right pleurostomy and closed reduction and immobilization of the left clavicle were also performed. The pulmonary contusions and the right renal hematoma were treated conservatively.

The patient had no significant medical history.

The patient had no significant personal or family medical history.

The patient was then referred 24 h later to our tertiary hepato-bilio-pancreatic (HBP) center for subsequent treatment.

A high-output biliary fistula which drained externally was recorded.

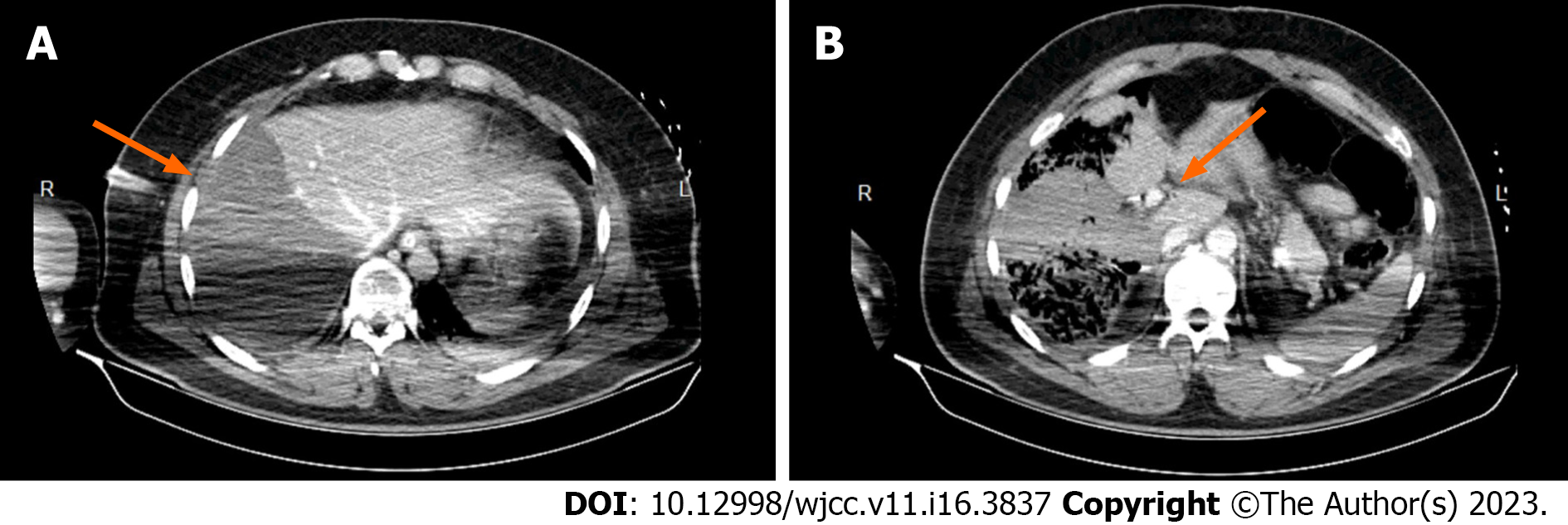

The CT scan showed no contrast uptake of the right hemiliver in the portal phase, no intrahepatic bile ducts dilatation, no peritoneal liquid and a mild right renal contusion (Figure 1). A high-output biliary fistula which drained externally was recorded.

Grade V liver trauma with severe laceration involving more than 75% of the right hemiliver, avulsion of the right portal vein and common bile duct, with massive hemoperitoneum, right hemopneumothorax, pulmonary contusions, right renal hematoma, II-X rib fractures and left clavicle fracture.

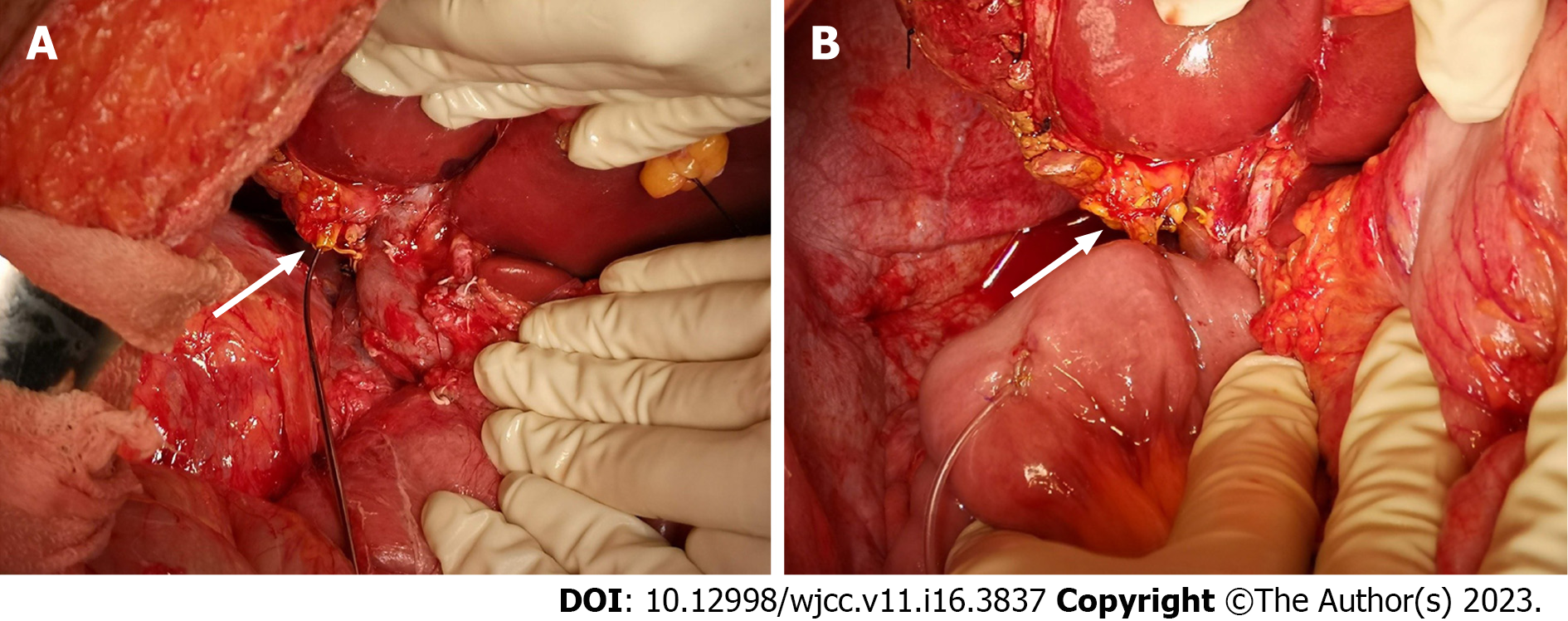

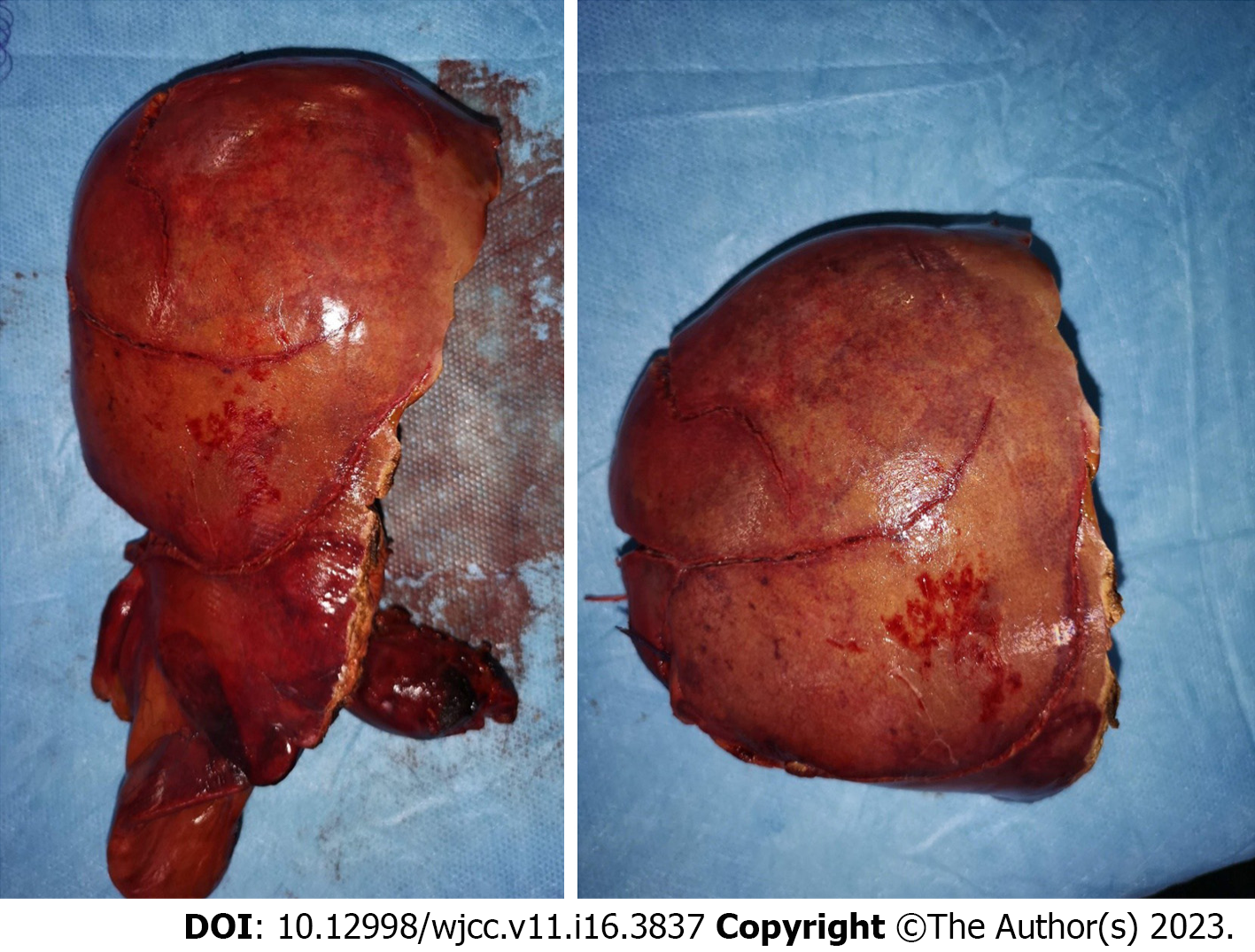

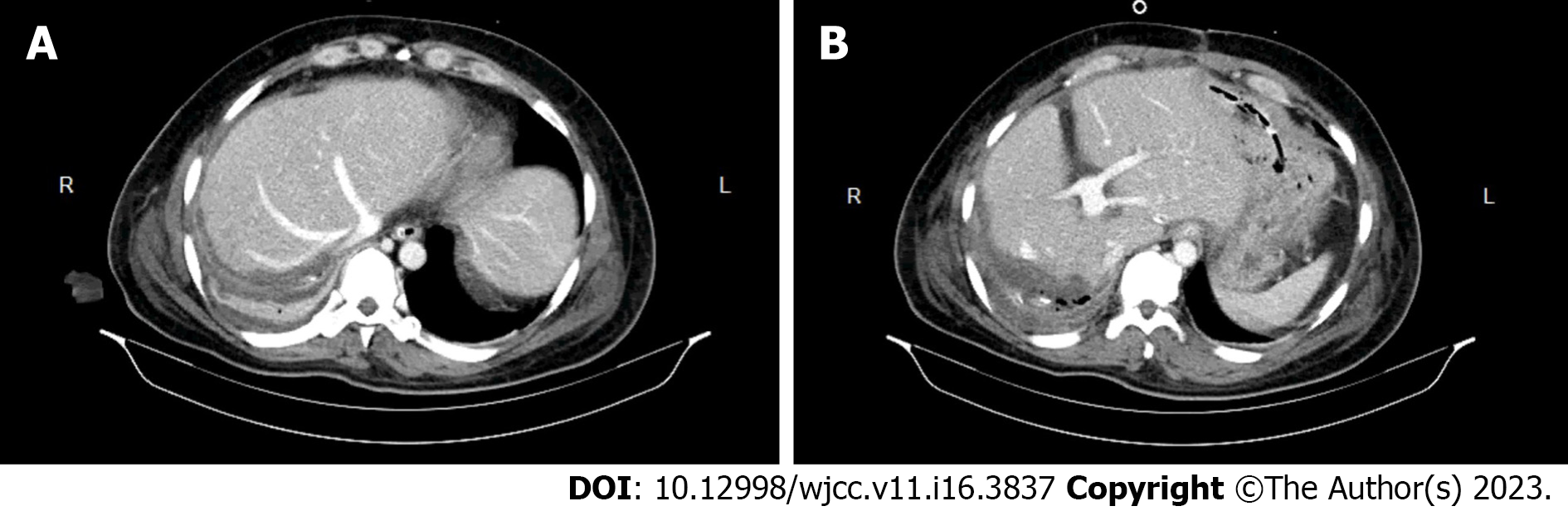

One day after the primary surgical intervention the second operation was performed, consisting of depacking, a right hepatectomy and Roux-en-Y hepatico-jejunostomy (using the stump of the common hepatic duct) protected by Wietzel external biliary drainage (Figures 2 and 3). The postoperative CT scan performed in postoperative day (POD) 6 showed the normal aspect of the remnant liver (Figure 4).

On POD 4, the onset of bile output through the subhepatic surgical drain was recorded and had increased progressively to 700 mL/d in POD 9. On POD 10, surgical reintervention was urged for high output anastomotic leakage. Intraoperatively, we diagnosed an anastomotic leakage and dubious vitality of the common bile duct stump. Therefore, we performed a redo cholangio-jejunostomy (using the left bile duct), protected by Wietzel external biliary drainage.

The intensive care unit stay had a total length of 4 d, as follows: 1 d in the emergency trauma center and 3 d in our center (2 d following the operation for right hemihepatectomy, 1 d following the intervention for biliary leakage). The patient was administered Piperacillin/tazobactam and Colistin. Blood products were used prior to and during the first operation performed in the primary emergency trauma center because the patient was admitted in hemorrhagic shock. Only 1 unit of blood was used in our tertiary referral center during the operation for right hemihepatectomy, and no blood products were used during the operation for biliary leakage.

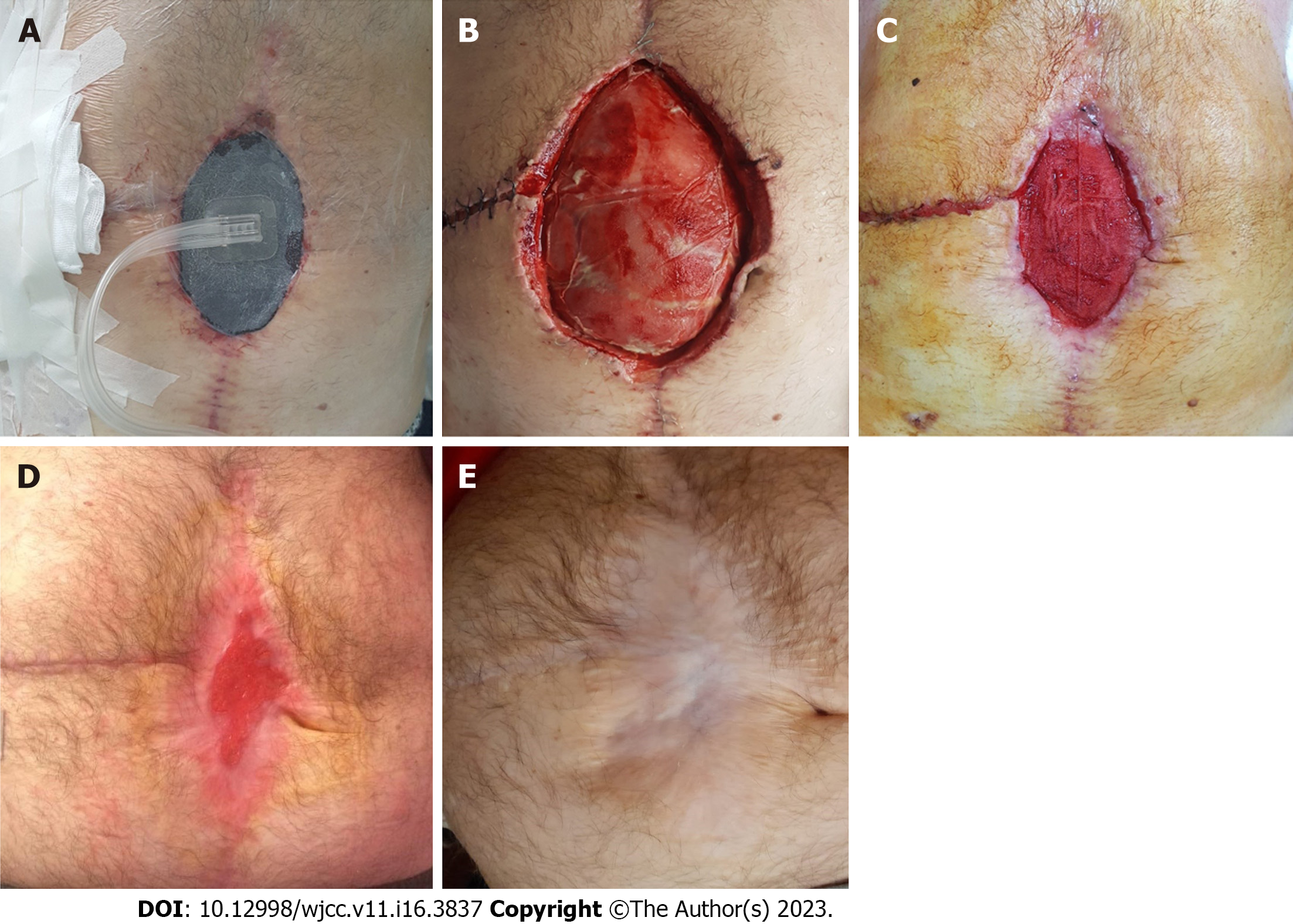

The postoperative period was marked by a surgical incisional site incomplete evisceration that was managed non-operatively by means of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT). The patient was discharged on POD 30, after a remaining uneventful course, with outcare NPWT, until the complete healing of the surgical wound after 4 mo postoperatively (Figure 5).

A follow-up ultrasound was performed at 1, 3, and 6 mo, showing no complications; the external biliary drainage was removed after 6 mo prior to cholangiography control. The patient fully recovered, as there were no other long-term complications encountered; currently the overall survival is 55 mo.

Although most liver traumas are successfully treated by NOM, which reduced the morbidity and mortality rates of these patients, interventional therapy still has a role in the management of complex liver injuries.

However, cases of severe blunt liver injury that associate hemodynamic instability after initial fluid resuscitation carry a high risk of hypovolemic shock and death, especially when other abdominal or thoracic lesions coexist; therefore, the current therapeutic conduct in such cases is the OM[3,5,10]. In this regard, the main goal of the primary surgery conducted in an emergency setting should be to secure efficient hemostasis by damage control surgery[15]. In the absence of major bleeding sites, it is usually suitable to employ techniques such as: compression, electrocautery, bipolar devices or suturing the liver parenchyma[16,17]. Major hemorrhage, however, may impose techniques such as: hepatic packing, direct vessel repair under vascular control, vessel ligation, shunting maneuvers, balloon tamponade or hepatic vascular isolation or exclusion[18]. Literature data clearly emphasizes that major resections should be avoided whenever possible upon this primary surgical intervention[4].

Studies that have investigated the outcomes of damage control surgery came to the conclusion that the packing procedure is part of a whole “damage control” strategy[19]. Even after a well conducted perihepatic packing procedure, some patients present active hemorrhage generated from deep injured vessels. In such cases, these patients are managed in the multidisciplinary setting, by selective angioembolization techniques performed by the interventional radiologists[3]. Some severe patients that still present with active bleeding following the aforementioned procedures are quickly subjected to a second packing procedure, because time is of essence in order to avoid the onset of the mortality associated “lethal triad” (i.e., acidosis, hypothermia and coagulopathy)[19]. The efficient perihepatic packing cannot be defined using an optimal number of gauzes[20]; it is important to avoid excessive packing in order to prevent abdominal compartment syndrome[19]. It is generally considered that packing is best removed after 48 h[21].

When vascular avulsion is present, it is vital to identify the injured vessels. In the case of hepatic artery injury, selective ligation is suitable whenever the repair of the vessel is not feasible. If the right hepatic artery needs to be ligated, cholecystectomy is recommended in order to avoid necrosis of the gallbladder[22,23]; this was not the case with our patient, as he had previously undergone chole

In the case of extensive parenchymal damage with insufficient liver remnant, liver transplant is to be considered[23]. Liver transplantation completes the therapeutic armamentum, and should be considered the last therapeutic alternative when the previously mentioned procedures prove unsuccessful in achieving hemodynamic stability, and complete hepatectomy is the last resort in bleeding control[1]. Literature data on this topic are very scarce[24]; nonetheless, the generally accepted indications are: Uncontrollable hemorrhage following damage control surgery, extensive and complex hepatic injuries not correctable by surgical procedures, unrepairable injuries of the portal vein, hepatic veins or bile ducts, trauma related acute liver failure due to trauma, and hepatic necrosis[25]. The liver transplantation decision should be thoroughly evaluated and implies the identification of those patients unfit for transplant, that present severe sepsis, multiple system organ failure, or associated severe organ injuries[24,25].

Liver trauma leads to a great variety of intra- and/or extrahepatic bile duct injuries; unfortunately, few studies have evaluated the management of bile leakage according to the location of the injured bile duct; therefore, the therapeutic management is controversial[10]. Literature states that the moment of detection raises issues of great importance. Because of the vague symptoms at presentation, delayed diagnosis can often occur, leading to high mortality and morbidity rates, through bacterial or fungal peritonitis, intractable bile leakage, haemobilia, pseudoaneurysms, or biliocutaneous fistula, and septic shock[10,14]. Thus, great importance must be given to early detection and proper management of bile leakage following liver trauma[14].

As stated earlier, due to the patient’s hemodynamic instability, the goal of the above mentioned primary emergency damage control surgery is to rapidly control the hemorrhage. Studies show that if a bile duct injury is diagnosed upon this primary procedure, the risks of performing extensive procedures such as liver resection and/or bile duct reconstruction are greater than the provided benefits, therefore it is generally accepted that the management of the injured bile ducts will be postponed and conducted at a later time[10].

Recent literature data consider applying adequate therapeutic management according to the extent of the injury and to the bile duct’s location. Certain studies have reported promising results following the nonoperative management of peripheral bile duct injuries by using percutaneous drainage procedures and early endoscopic biliary stenting, thus providing a safe alternative and avoiding open surgery[10,14,26,27]. Some of the major drawbacks are: the difficulty in performing early Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and internal stenting in hemodynamically unstable patients, and post-ERCP cholangitis, resulting in hepatic abscess and consecutive liver rupture[28]. In an attempt to overcome these shortcomings, some centers avoided ERCP stenting and stent removal procedures, and adopted first-line percutaneous intraperitoneal drainage; their updated experience shows comparable outcomes[10,14]. Previous studies reporting the setting of severe liver trauma show that peripheral bile duct injuries can be managed by the above mentioned nonoperative treatments. However, the appropriate timing and the choice of therapeutic management are still subject of debate[10,26,29,30].

Recent studies also show that post-traumatic sections of a central bile duct are rare and often difficult to diagnose preoperatively[30]. The attempt to determine the degree of the bile duct injury with massive fluid collection by means of preoperative CT or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) scan is close to impossible[10]; therefore, as a diagnostic alternative, some authors promote the use of technetium-99 m trimethylbromoimino-diacetic acid scan for early detection on post-traumatic days 5 to 7[14]. Nonetheless, some studies suggest that a preoperative CT exam shows a strong correlation between the minimal distance measured from the portal pedicle to the parenchymal traumatic injury and the existence of a bile duct injury[14].

Given the emergency setting scenario of the case under discussion, the MPCR exam was not taken into consideration due to long delays in both waiting list times and performance of examination. In addition, properly conducted perihepatic packing can cause artefacts and major anatomic distortions that render the MRCP exam inconclusive. We considered that intraoperative exploration of the bile ducts combined with intraoperative cholangiography, whenever deemed necessary, is optimal for this type of case with severe hepato-biliary trauma managed with emergency packing as a first step of the surgical treatment. For example, we did not perform intraoperative cholangiography, as the surgical exploration of the bile ducts with a malleable metal probe was considered enough.

On the other hand, a central bile duct injury will require aggressive surgical treatment, performed once the patient’s condition is stable; however, currently, there is no consensual therapeutic conduct available in the literature regarding central bile duct injuries; consequently, the management of such an injury must be tailored[10]. Literature data report successful outcomes after techniques, such as, liver resection, reconstruction of the injured bile ducts by Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy[31], and /or primary repair of the injured duct with T-tube insertion[32]. Biliary leakage by anastomotic fistula is a possible complication, as shown by the current case – i.e., the hepaticojejunostomy was redone in a subsequent intervention. There are also reports available on central bile duct injuries repaired by primary suture and complemented by ERCP and internal stenting as an option for biliary decom

Given the complexity of the encountered lesions, we did not consider it appropriate to adopt any other therapeutic approach. A reconstruction of the right portal vein and right hepatic artery was not considered feasible, because a significant portion of the right portal vein was missing (due to associated trauma and to surgical hemostasis during the damage control surgery), because of the long ischemic time of the right hemiliver, and finally because the parenchyma of the right hemiliver was almost completely damaged by trauma.

Of note, the ligation of the right hepatic artery performed upon the damage control laparotomy was considered mandatory due to remanent significant parenchymal bleeding despite right portal vein ligation. Moreover, the right hemiliver was already compromised by the laceration and associated right portal vein avulsion. Therefore, right hepatectomy would have been needed even in the absence of the right hepatic artery ligation.

NPWT facilitates healing by reducing edema, draining excess fluids, and eliminating barriers to cellular proliferation[33,34]. NPWT can successfully promote the healing of infected wounds, diabetic foot wounds, laparotomy incisions, as well as other chronic conditions[35,36]. In our case, it successfully facilitated the closure of the surgical incisional site evisceration allowing for complete healing, thus avoiding the need for additional surgery and exposing the patient to fewer risks.

This case clearly supports that a favorable outcome in severe liver trauma with associated vascular and biliary injuries is achieved thru proper therapeutic management, conducted in a tertiary referral HBP center, where stepwise and complex surgical approach is mandatory.

The present study is included in a wider retrospective research entitled “Liver Trauma”, as part of a doctoral dissertation, developed by Bianca Mitricof, Ph D student at “Titu Maiorescu” Doctoral School of Medicine, Bucharest, Romania with Irinel Popescu as thesis coordinator. The authors would like to thank Luiza-Anca Kraft, Associate Professor in “Carol I” National Defense University, Bucharest, Romania, for the language editing work.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Romania

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ghimire R, Nepal; Govindarajan KK, India; He YH, China S-Editor: Liu XF L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Krawczyk M, Grąt M, Adam R, Polak WG, Klempnauer J, Pinna A, Di Benedetto F, Filipponi F, Senninger N, Foss A, Rufián-Peña S, Bennet W, Pratschke J, Paul A, Settmacher U, Rossi G, Salizzoni M, Fernandez-Selles C, Martínez de Rituerto ST, Gómez-Bravo MA, Pirenne J, Detry O, Majno PE, Nemec P, Bechstein WO, Bartels M, Nadalin S, Pruvot FR, Mirza DF, Lupo L, Colledan M, Tisone G, Ringers J, Daniel J, Charco Torra R, Moreno González E, Bañares Cañizares R, Cuervas-Mons Martinez V, San Juan Rodríguez F, Yilmaz S, Remiszewski P; European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association (ELITA). Liver Transplantation for Hepatic Trauma: A Study From the European Liver Transplant Registry. Transplantation. 2016;100:2372-2381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Matthes G, Stengel D, Seifert J, Rademacher G, Mutze S, Ekkernkamp A. Blunt liver injuries in polytrauma: results from a cohort study with the regular use of whole-body helical computed tomography. World J Surg. 2003;27:1124-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Coccolini F, Coimbra R, Ordonez C, Kluger Y, Vega F, Moore EE, Biffl W, Peitzman A, Horer T, Abu-Zidan FM, Sartelli M, Fraga GP, Cicuttin E, Ansaloni L, Parra MW, Millán M, DeAngelis N, Inaba K, Velmahos G, Maier R, Khokha V, Sakakushev B, Augustin G, di Saverio S, Pikoulis E, Chirica M, Reva V, Leppaniemi A, Manchev V, Chiarugi M, Damaskos D, Weber D, Parry N, Demetrashvili Z, Civil I, Napolitano L, Corbella D, Catena F; WSES expert panel. Liver trauma: WSES 2020 guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Barcu A, Mitricof B, Verdea C, Bălănescu L, Tomescu D, Droc G, Lupescu I, Hrehoreţ D, Braşoveanu V, Popescu I, Botea F. Definitive Surgery for Liver Trauma in a Tertiary HPB Center (with video). Chirurgia (Bucur). 2021;116:678-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Saviano A, Ojetti V, Zanza C, Franceschi F, Longhitano Y, Martuscelli E, Maiese A, Volonnino G, Bertozzi G, Ferrara M, La Russa R. Liver Trauma: Management in the Emergency Setting and Medico-Legal Implications. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | García IC, Villalba JS, Iovino D, Franchi C, Iori V, Pettinato G, Inversini D, Amico F, Ietto G. Liver Trauma: Until When We Have to Delay Surgery? A Review. Life (Basel). 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mitricof B, Brasoveanu V, Hrehoret D, Barcu A, Picu N, Flutur E, Tomescu D, Droc G, Lupescu I, Popescu I, Botea F. Surgical treatment for severe liver injuries: a single-center experience. Minerva Chir. 2020;75:92-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hommes M, Navsaria PH, Schipper IB, Krige JE, Kahn D, Nicol AJ. Management of blunt liver trauma in 134 severely injured patients. Injury. 2015;46:837-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kozar RA, Moore FA, Moore EE, West M, Cocanour CS, Davis J, Biffl WL, McIntyre RC Jr. Western Trauma Association critical decisions in trauma: nonoperative management of adult blunt hepatic trauma. J Trauma. 2009;67:1144-8; discussion 1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kagoura M, Monden K, Sadamori H, Hioki M, Ohno S, Takakura N. Outcomes and management of delayed complication after severe blunt liver injury. BMC Surg. 2022;22:241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Oniscu GC, Parks RW, Garden OJ. Classification of liver and pancreatic trauma. HPB (Oxford). 2006;8:4-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Melloul E, Denys A, Demartines N. Management of severe blunt hepatic injury in the era of computed tomography and transarterial embolization: A systematic review and critical appraisal of the literature. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:468-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fodor M, Primavesi F, Morell-Hofert D, Haselbacher M, Braunwarth E, Cardini B, Gassner E, Öfner D, Stättner S. Non-operative management of blunt hepatic and splenic injuries-practical aspects and value of radiological scoring systems. Eur Surg. 2018;50:285-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stonelake S, Ali S, Pinkey B, Ong E, Anbarasan R, McGuirk S, Perera T, Mirza D, Muiesan P, Sharif K. Fifteen-Year Single-Center Experience of Biliary Complications in Liver Trauma Patients: Changes in the Management of Posttraumatic Bile Leak. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2021;31:245-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Küçükaslan H, Tayar S, Oğuz Ş, Topaloglu S, Geze Saatci S, Şenel AC, Calik A. The role of liver resection in the management of severe blunt liver trauma. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2022;29:122-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Letoublon C, Reche F, Abba J, Arvieux C. Damage control laparotomy. J Visc Surg. 2011;148:e366-e370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Coccolini F, Montori G, Catena F, Di Saverio S, Biffl W, Moore EE, Peitzman AB, Rizoli S, Tugnoli G, Sartelli M, Manfredi R, Ansaloni L. Liver trauma: WSES position paper. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kodadek LM, Efron DT, Haut ER. Intrahepatic Balloon Tamponade for Penetrating Liver Injury: Rarely Needed but Highly Effective. World J Surg. 2019;43:486-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Martellotto S, Melot C, Raux M, Chereau N, Menegaux F. Depacked patients who underwent a shortened perihepatic packing for severe blunt liver trauma have a high survival rate: 20 years of experience in a level I trauma center. Surgeon. 2022;20:e20-e25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Baldoni F, Di Saverio S, Antonacci N, Coniglio C, Giugni A, Montanari N, Biscardi A, Villani S, Gordini G, Tugnoli G. Refinement in the technique of perihepatic packing: a safe and effective surgical hemostasis and multidisciplinary approach can improve the outcome in severe liver trauma. Am J Surg. 2011;201:e5-e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ordoñez C, Pino L, Badiel M, Sanchez A, Loaiza J, Ramirez O, Rosso F, García A, Granados M, Ospina G, Peitzman A, Puyana JC, Parra MW. The 1-2-3 approach to abdominal packing. World J Surg. 2012;36:2761-2766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | David Richardson J, Franklin GA, Lukan JK, Carrillo EH, Spain DA, Miller FB, Wilson MA, Polk HC Jr, Flint LM. Evolution in the management of hepatic trauma: a 25-year perspective. Ann Surg. 2000;232:324-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Peitzman AB, Marsh JW. Advanced operative techniques in the management of complex liver injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:765-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Patrono D, Brunati A, Romagnoli R, Salizzoni M. Liver transplantation after severe hepatic trauma: a sustainable practice. A single-center experience and review of the literature. Clin Transplant. 2013;27:E528-E537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ribeiro MA Jr, Medrado MB, Rosa OM, Silva AJ, Fontana MP, Cruvinel-Neto J, Fonseca AZ. Liver transplantation after severe hepatic trauma: current indications and results. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2015;28:286-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tamura N, Ishihara S, Kuriyama A, Watanabe S, Suzuki K. Long-term follow-up after non-operative management of biloma due to blunt liver injury. World J Surg. 2015;39:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kulaylat AN, Stokes AL, Engbrecht BW, McIntyre JS, Rzucidlo SE, Cilley RE. Traumatic bile leaks from blunt liver injury in children: a multidisciplinary and minimally invasive approach to management. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:424-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hommes M, Kazemier G, Schep NW, Kuipers EJ, Schipper IB. Management of biliary complications following damage control surgery for liver trauma. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2013;39:511-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Paffrath T, Lefering R, Flohé S; TraumaRegister DGU. How to define severely injured patients? -- an Injury Severity Score (ISS) based approach alone is not sufficient. Injury. 2014;45 Suppl 3:S64-S69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Oo J, Smith M, Ban EJ, Clements W, Tagkalidis P, Fitzgerald M, Pilgrim CHC. Management of bile leak following blunt liver injury: a proposed guideline. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91:1164-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Rodriguez-Montes JA, Rojo E, Martín LG. Complications following repair of extrahepatic bile duct injuries after blunt abdominal trauma. World J Surg. 2001;25:1313-1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zago TM, Pereira BM, Calderan TR, Hirano ES, Fraga GP. Extrahepatic duct injury in blunt trauma: two case reports and a literature review. Indian J Surg. 2014;76:303-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bellot GL, Dong X, Lahiri A, Sebastin SJ, Batinic-Haberle I, Pervaiz S, Puhaindran ME. MnSOD is implicated in accelerated wound healing upon Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT): A case in point for MnSOD mimetics as adjuvants for wound management. Redox Biol. 2019;20:307-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Song YP, Wang L, Yuan BF, Shen HW, Du L, Cai JY, Chen HL. Negative-pressure wound therapy for III/IV pressure injuries: A meta-analysis. Wound Repair Regen. 2021;29:20-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Cirocchi R, Birindelli A, Biffl WL, Mutafchiyski V, Popivanov G, Chiara O, Tugnoli G, Di Saverio S. What is the effectiveness of the negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) in patients treated with open abdomen technique? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81:575-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sahebally SM, McKevitt K, Stephens I, Fitzpatrick F, Deasy J, Burke JP, McNamara D. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy for Closed Laparotomy Incisions in General and Colorectal Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:e183467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |