Published online May 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i15.3658

Peer-review started: March 6, 2023

First decision: March 24, 2023

Revised: March 26, 2023

Accepted: April 17, 2023

Article in press: April 17, 2023

Published online: May 26, 2023

Processing time: 80 Days and 12.6 Hours

Pulmonary sequestrations often lead to serious complications such as infections, tuberculosis, fatal hemoptysis, cardiovascular problems, and even malignant degeneration, but it is rarely documented with medium and large vessel vasculi

A 44-year-old man with a history of acute Stanford type A aortic dissection status post-reconstructive surgery five years ago. The contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest at that time had also revealed an intralobar pulmonary sequestration in the left lower lung region, and the angiography also presented perivascular changes with mild mural thickening and wall enhancement, which indicated mild vasculitis. The intralobar pulmonary sequestration in the left lower lung region was long-term unprocessed, which was probably associated with his intermittent chest tightness since no specific medical findings were detected but only positive sputum culture with mycobacterium avium-intracellular complex and Aspergillus. We performed uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery with wedge resection of the left lower lung. Hypervascularity over the parietal pleura, engorgement of the bronchus due to a moderate amount of mucus, and firm adhesion of the lesion to the thoracic aorta were histopathologically noticed.

We hypothesized that a long-term pulmonary sequestration-related bacterial or fungal infection can result in focal infectious aortitis gradually, which may threateningly aggravate the formation of aortic dissection.

Core Tip: We present a case of a 44-year-old man with history of acute Stanford type A aortic dissection status post reconstructive surgery five years ago. An intralobar pulmonary sequestration in the left lower lung region was also noticed accidently, but without further management at that time. Since symptoms of chest tightness bothered him in recent one year, he came to Thoracic surgery outpatient department where slowly growing of the lung lesion was noticed. Admission was suggested for resection of the left lower lung.

- Citation: Wang YJ, Chen YY, Lin GH. Relationship between intralobar pulmonary sequestration and type A aortic dissection: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(15): 3658-3663

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i15/3658.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i15.3658

Pulmonary sequestrations are associated with serious complications including bacterial and fungal infections, tuberculosis, massive hemothorax, serious hemoptysis, cardiovascular events, malignant degeneration, and even rarely but fatal medium and large vessel vasculitis. Aortitis as a form of large vessel vasculitis caused mainly by rheumatological inflammation or infection potentially results in acute aortic syndromes, including aortic dissection. We herein present a 44-year-old man with a history of acute Stanford type A aortic dissection status post-reconstructive surgery five years ago. The patient presented with a long-term unprocessed intralobar pulmonary sequestration in the left lower lung region, which was probably associated with intermittent chest tightness since no specific medical findings were detected. Furthermore, sputum culture was positive for mycobacterium avium-intracellular complex and Aspergillus. We performed uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery with wedge resection of the left lower lung. Since the patient was relatively young and had no history of systemic hypertension, we hypothesized that a long-term pulmonary sequestration-related bacterial and fungal infection can result in focal infectious aortitis gradually and aggravate the formation of aortic dissection.

Intermittent chest tightness for one year.

A 44-year-old man was diagnosed with acute aortic dissection, Stanford type A five years ago, and he had undergone reconstruction surgery. The contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the chest had also revealed intralobar pulmonary sequestration over medial region of the lower lobe of the left lung, but attention was not given to the pulmonary sequestration at that time. He visited Thoracic Surgery outpatient department due to intermittent chest tightness for one year and symptoms exacerbated recently. Except for the lung lesion noted five years ago and got slowly growing as time via image of CT, there’s no other specific findings. The patient was admitted to deal with his long-term intralobar pulmonary sequestration.

The patient has history of acute aortic dissection, Stanford type A five years ago. He received reconstruction of the ascending aorta and the aortic arch up to the branching out of the right innominate artery about five years ago. Besides, he also suffered from hypertension and under regular medication control. Otherwise, there’s no other systemic disease.

The patient exhibited normal social functioning and self-care. He’s a non-smoker, and drink socially. There was no specific family history of cardiovascular disease or any other malignancy.

Physical examination revealed no specific findings. The chest wall is well expansion while breathing, no wheezing, or crackles. There’s no body weight loss in recent 6 mo or pitting edema over extremities.

Laboratory studies revealed no leukocytosis, but mild elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level (0.97 mg/dL). Sputum culture was collected and revealed positive results for mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex and aspergillus.

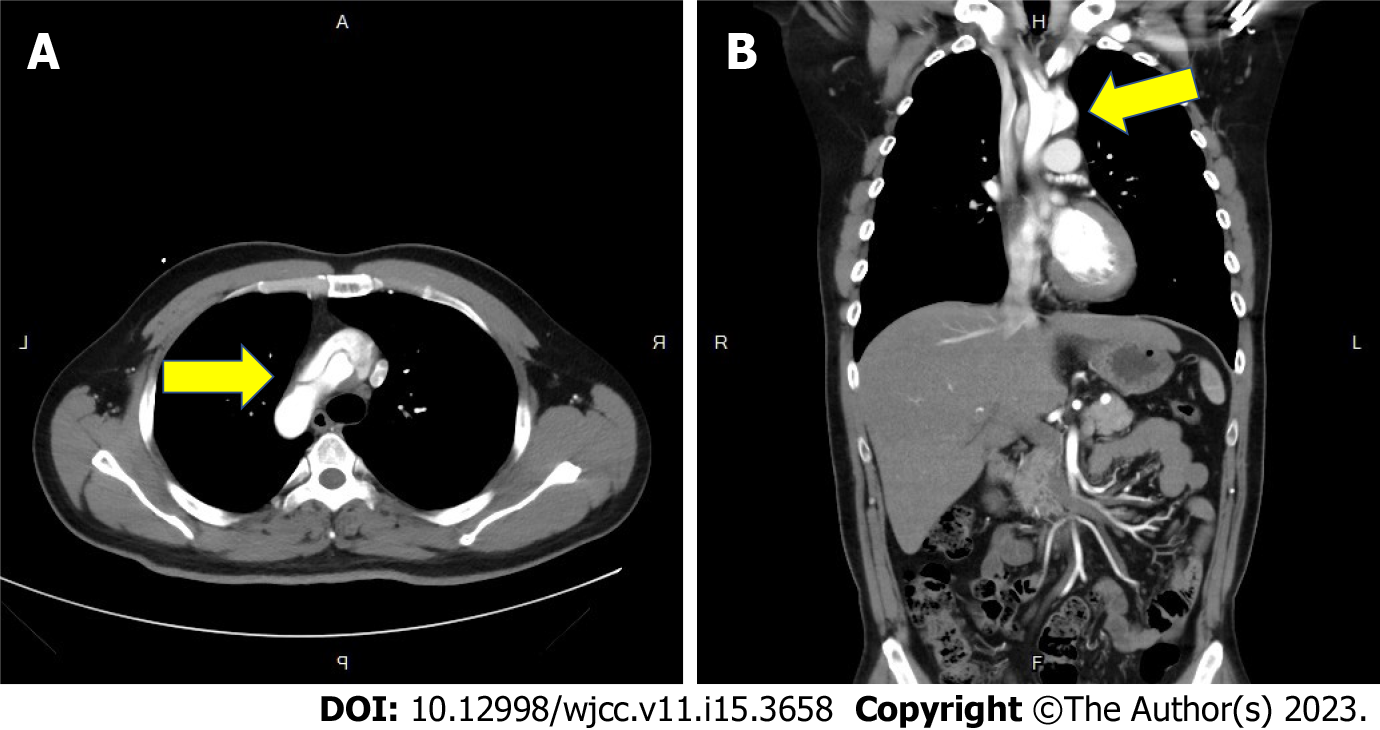

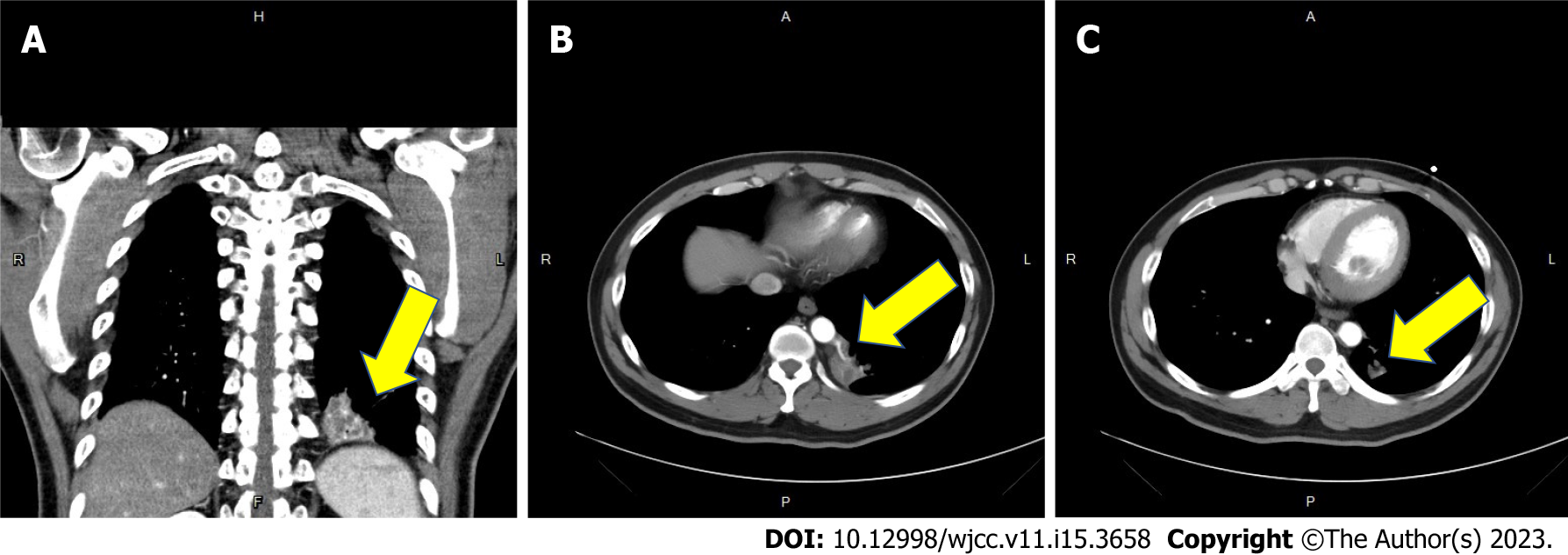

Five years ago, the contrast-enhanced CT of the chest revealed Type A aortic dissection with intimal flap involving the ascending aorta, the aortic arch (arrow in Figure 1A) and the common carotid arteries bilaterally (Figure 1B). Besides the diagnosis of aortic dissection, a focal heterogeneous area with cystic change and patchy consolidation in the medial region of left lower lung (arrow in Figure 2A) with two aberrant arteries (arrow in Figure 2B) arising from the thoracic aorta supplying this area was also noticed. CT angiography also revealed mild mural thickening and wall enhancement which may indicate mild vasculitis (arrow in Figure 2C).

Under the impression of long-term intralobar pulmonary sequestration, the patient was admitted for uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery with an extended wedge resection of the left lower lung.

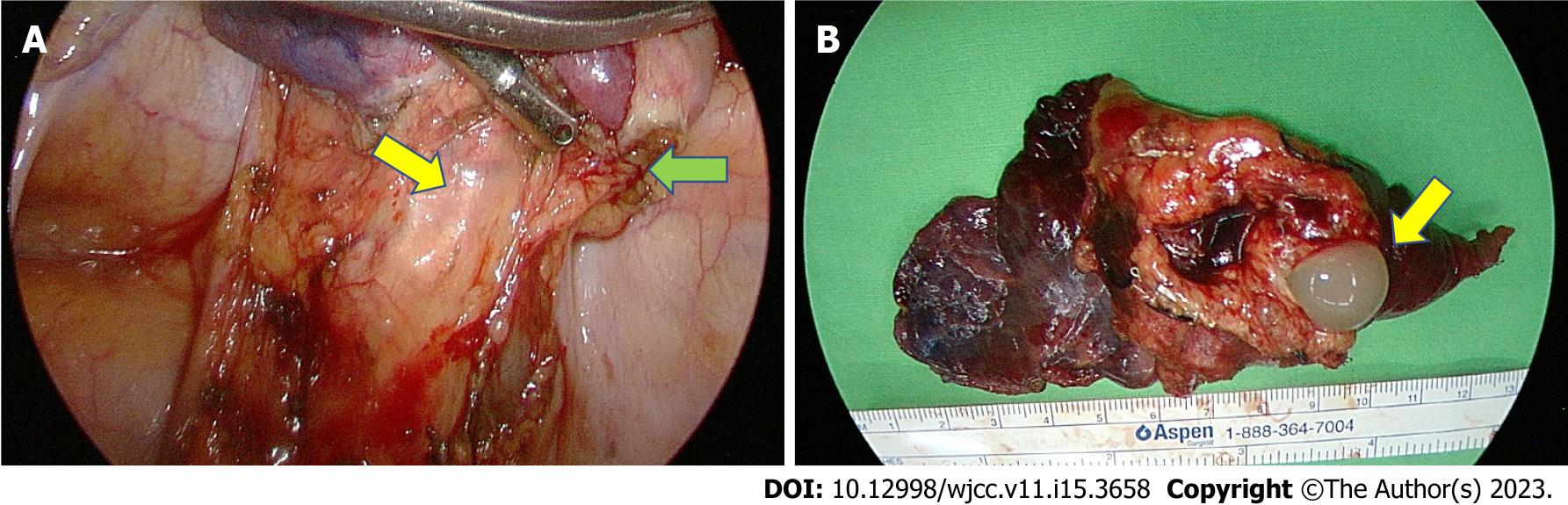

Firm adhesion of the sequestrated lung to the thoracic aorta and the two aberrant arteries originating from the thoracic aorta were identified (Figure 3A) and then resected by Endo GIA. Meanwhile, hypervascularity over the parietal pleura as well as engorgement of the bronchus were also noticed. The macroscopic findings revealed a solid pulmonary nodule about 10 cm × 4 cm × 2 cm in size with focal bronchial dilation containing hemorrhage and mucus (Figure 3B), calcification as well as extensive necrosis of the lung. Histopathological analysis revealed small bronchial duct hyperplasia along with two lymph nodes showing reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, with no evidence of malignancy.

Postoperative recovery was smooth, without any surgical complications, and the patient was discharged on the 4th postoperative day. Oral form empirical antibiotics was given for seven days.

The patient recovered well while outpatient department follow up. There’s no chest tightness or chest pain after the operation.

Pulmonary sequestrations are bronchopulmonary foregut malformations, usually characterized by a nonfunctional segmental lung tissue that dissociates from the normal tracheobronchial tree or the pulmonary arteries, and commonly appears in the lower lobes of the lung. Pulmonary sequestrations lead to serious complications: fungal infections, tuberculosis[1], fatal hemoptysis, massive hemothorax, cardiovascular problems[2], and even benign or malignant degeneration. Infected pulmonary sequestration due to mycobacteria, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex, occur rarely[1]. Malik et al[3] also demonstrated an asymptomatic intralobar pulmonary sequestration, associated with medium - and large vessel vasculitis[3].

Aortitis, which is defined as a form of large vessel vasculitis, is characterized by the inflammation of the aortic wall. Most cases of aortitis are either due to rheumatological causes, which include large vessel vasculitis, giant cell arteritis and Takayasu arteritis; or because of infectious diseases, with Salmonella, Staphylococcal species, and Streptococcus pneumoniae being the most commonly identified pathogens., Tuberculosis and syphilis are rare but potentially life-threatening causes[4]. In most cases of bacterial aortitis, a segment of the aortic wall with pre-existing pathology, such as an atherosclerotic plaque or aneurysm, is seeded by the bacteria via the vasa vasorum[5]. Acute aortic syndromes, like aortic dissection and rupture, can occur in such patients with aortitis[6]. Ryder et al[7] presented a case of a previously healthy 39-year-old man who succumbed to aortic dissection hours after the onset of symptoms. Aortitis was detected during the postmortem examination in this case[7]. They also identified a cohort of patients who presented with a subtype of isolated inflammatory aortitis, which was characterized by aggressive vasculitis with acute inflammatory infiltration. Park et al[8] also described a case of an 83-year-old woman, with a history of hypertension, who arrived at the emergency department with septic shock. Stanford type A aortic dissection was revealed by the chest CT scan initially. In the end, aortitis, without giant cells and caseous necrosis, was identified, when histopathological examination of the ascending aorta was performed after the emergency surgery[8]. In our case, biochemistry lab data showed mild elevated CRP level, indicated possible inflammatory status. CT angiography also revealed mild mural thickening and wall enhancement which may indicate mild vasculitis. The final pathology report of the resected specimens disclosed the diagnosis with extensive necrosis of the lung, hypervascularity and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia.

Since the patient, in our case, was young and without systemic hypertension, we hypothesize that a long-term pulmonary sequestration-related bacterial and fungal infection is likely to result in infectious aortitis gradually, which can, menacingly, contribute to aortic dissection.

Neglected pulmonary sequestrations may be associated to serious complication such as bacterial, fungal, or tuberculosis infection. Rarely, the infectious state result in aortitis, and the destruction of vascular epithelial tissue lead to aortic dissection. It is unusual but catastrophic, which can’t leave out of consideration.

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of the people in the Department of Surgery, Tri Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center. This report would not have been possible without their efforts in data collection and interprofessional collaboration in treating this patient.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Barik R, India; Wang T, China S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Shiota Y, Arikita H, Aoyama K, Horita N, Hiyama J, Ono T, Sasaki N, Taniyama K, Yamakido M. Pulmonary sequestration associated by Mycobacterium intracellulare infection. Intern Med. 2002;41:990-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fabre OH, Porte HL, Godart FR, Rey C, Wurtz AJ. Long-term cardiovascular consequences of undiagnosed intralobar pulmonary sequestration. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:1144-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Malik S, Khurana S, Vasudevan V, Gupta N. A rare case of underlying pulmonary sequestration in a patient with recently diagnosed medium and large vessel vasculitis. Lung India. 2014;31:176-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gornik HL, Creager MA. Aortitis. Circulation. 2008;117:3039-3051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 381] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Azar T, Berger DL. Adult intussusception. Ann Surg. 1997;226:134-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 648] [Cited by in RCA: 666] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nuenninghoff DM, Hunder GG, Christianson TJ, McClelland RL, Matteson EL. Incidence and predictors of large-artery complication (aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, and/or large-artery stenosis) in patients with giant cell arteritis: a population-based study over 50 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3522-3531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 384] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ryder HF, Tafe LJ, Burns CM. Fatal aortic dissection due to a fulminant variety of isolated aortitis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009;15:295-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Park BS, Min HK, Kang DK, Jun HJ, Hwang YH, Jang EJ, Jin K, Kim HK, Jang HJ, Song JW. Stanford type A aortic dissection secondary to infectious aortitis: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:485-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |