Published online May 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i15.3457

Peer-review started: January 9, 2023

First decision: February 2, 2023

Revised: March 2, 2023

Accepted: April 14, 2023

Article in press: April 14, 2023

Published online: May 26, 2023

Processing time: 136 Days and 6.5 Hours

Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a new and widely used approach; however, ever since the United States Food and Drug Administration warned against the use of surgical mesh, repairs performed using patients’ tissues [i.e. native tissue repair (NTR)] instead of mesh have attracted much attention. At our hospital, laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (the Shull method) was introduced in 2017. However, patients with more severe POP who have a long vaginal canal and overextended uterosacral ligaments may not be candidates for this procedure.

To validate a new NTR treatment for POP, we examined patients undergoing laparoscopic vaginal stump–round ligament fixation (the Kakinuma method).

The study patients were 30 individuals with POP who underwent surgery using the Kakinuma method between January 2020 and December 2021 and who were followed up for > 12 mo after surgery. We retrospectively examined surgical outcomes for surgery duration, blood loss, intraoperative complications, and incidence of recurrence. The Kakinuma method involves round ligament suturing and fixation on both sides, effectively lifting the vaginal stump after laparoscopic hysterectomy.

The patients’ mean age was 66.5 ± 9.1 (45-82) years, gravidity was 3.1 ± 1.4 (2-7), parity was 2.5 ± 0.6 (2-4) times, and body mass index was 24.5 ± 3.3 (20.9-32.8) kg/m2. According to the POP quantification stage classification, there were 8 patients with stage II, 11 with stage III, and 11 with stage IV. The mean surgery duration was 113.4 ± 22.6 (88-148) min, and the mean blood loss was 26.5 ± 39.7 (10-150) mL. There were no perioperative complications. None of the patients exhibited reduced activities of daily living or cognitive impairment after hospital discharge. No cases of POP recurrence were observed 12 mo after the operation.

The Kakinuma method, similar to conventional NTR, may be an effective treatment for POP.

Core Tip: The conventional method of performing repairs using patients’ own tissues [also called native tissue repair (NTR)] instead of using mesh is being reconsidered. NTR surgical techniques include vaginal stump–uterosacral ligament fixation (Shull method), which has reported satisfactory surgical outcomes. Many patients with severe pelvic organ prolapse have long vaginal canals and overstretched sacral uterine ligaments, which prevent effective repair using the Shull method. The Kakinuma method (laparoscopic vaginal stump–round ligament fixation) lifts the vaginal stump to an anatomically higher position. This method is an effective treatment method for pelvic organ prolapse, similar to conventional NTR.

- Citation: Kakinuma T, Kaneko A, Kakinuma K, Imai K, Takeshima N, Ohwada M. New native tissue repair for pelvic organ prolapse: Medium-term outcomes of laparoscopic vaginal stump–round ligament fixation. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(15): 3457-3463

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i15/3457.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i15.3457

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is caused by factors such as high parity and aging and refers to the abnormal positioning of pelvic organs caused by the loosening of pelvic floor muscles and endopelvic fascia. POP often manifests as a pelvic floor hernia.

Epidemiological surveys in Western countries have reported that POP is observed in 44% of women who have experienced vaginal childbirth[1], and 11%-20% of women undergo surgery for POP or urinary incontinence by age 80 years[2-4]. As the overall population ages, the prevalence of POP has also been increasing[5,6]. POP frequently occurs in middle-aged and older women and considerably impacts their quality of life (QOL). The treatment of POP aims to eliminate serious symptoms, such as lower urinary tract symptoms, sexual dysfunction, and the feeling of organ prolapse, and improve QOL by correcting organ position. Pelvic floor exercises are effective for the functional recovery of pelvic floor muscles in early-stage mild POP and can prevent exacerbation of symptoms[7]. The method of fixing the uterus to the deep part of the vagina by pessary placement is a popular conservative therapy[8]. Surgery is selected for patients with complications such as vaginal ulcers due to pessary insertion and when QOL does not improve even after conservative treatment[9].

In Japan, anterior and posterior colporrhaphies have traditionally been performed as surgical procedures following total vaginal hysterectomy. However, this surgical technique has the disadvantages of a high recurrence rate (20%-30%) and lack of consideration for postoperative sexual function[2,10].

With the relatively recent introduction of mesh surgery, surgical therapy for POP has made dramatic progress. However, it is associated with problems such as postoperative infection and dyspareunia due to mesh dislodging (erosion) and hardening. In addition, the United States Food and Drug Administration had issued an alert against it[11]. Consequently, there is a strong impetus to revisit repairs that use patients’ own tissues instead of mesh (referred to as native tissue repair or NTR), a conventional method. NTR techniques include vaginal stump-uterosacral ligament fixation (Shull method), which involves reconstruction of the vaginal canal axis without mesh, similar to laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (LSC). Satisfactory outcomes have previously been reported for the laparoscopic Shull method[12]. However, effective surgical repair using the Shull method may not be possible for patients with more severe POP, e.g., patients with long vaginal canals and overextended uterosacral ligaments, given that this method only fixes the vaginal stump and uterosacral ligaments. The round ligament gains some muscle fibers during prenatal development and eventually assumes an anatomically higher position than the uterosacral ligaments[13].

To solve this problem, we devised a novel laparoscopic vaginal stump–round ligament fixation (the Kakinuma method) for laparoscopic fixation of the vaginal stump to the round ligaments (histologically strong tissues that are anatomically higher than the uterosacral ligaments) for patients with moderate-to-severe POP. This paper comprised a preliminary clinical investigation of the efficacy and safety of the Kakinuma method for treating POP.

This study was conducted with the approval of the relevant ethical board. The subjects were 30 patients who underwent laparoscopic vaginal stump–round ligament fixation (Kakinuma method) for POP following informed consent from January 2020 to December 2021 and could be followed up for more than 12 mo after surgery. We retrospectively examined surgical outcomes for surgery duration, blood loss, intraoperative complications, and incidence of recurrence.

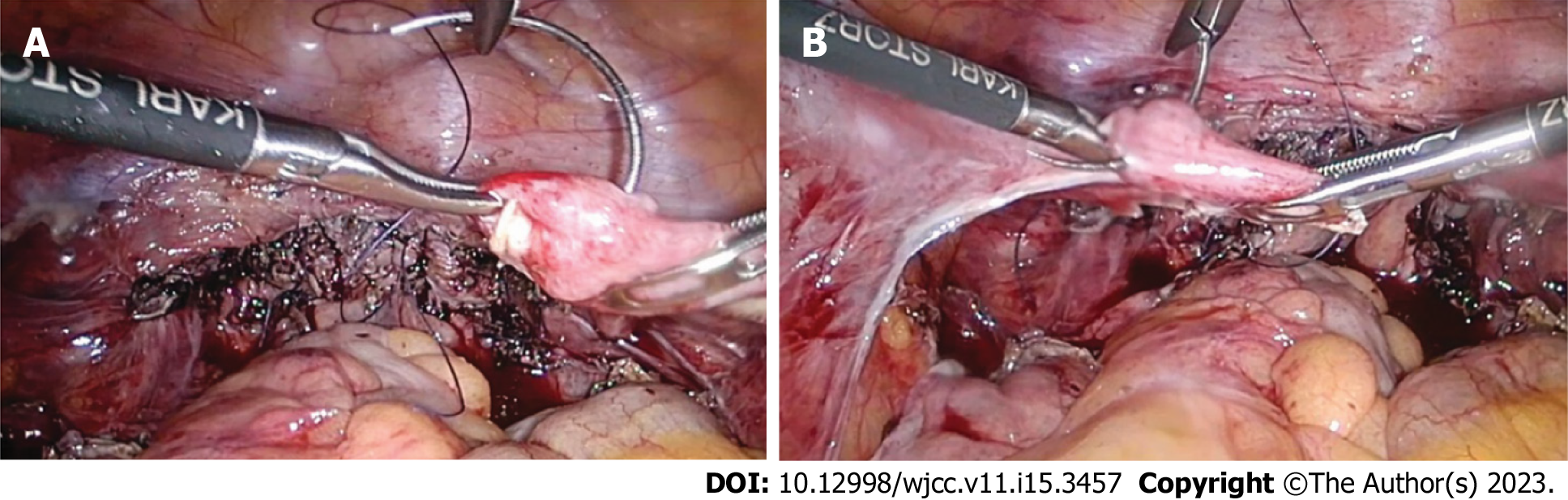

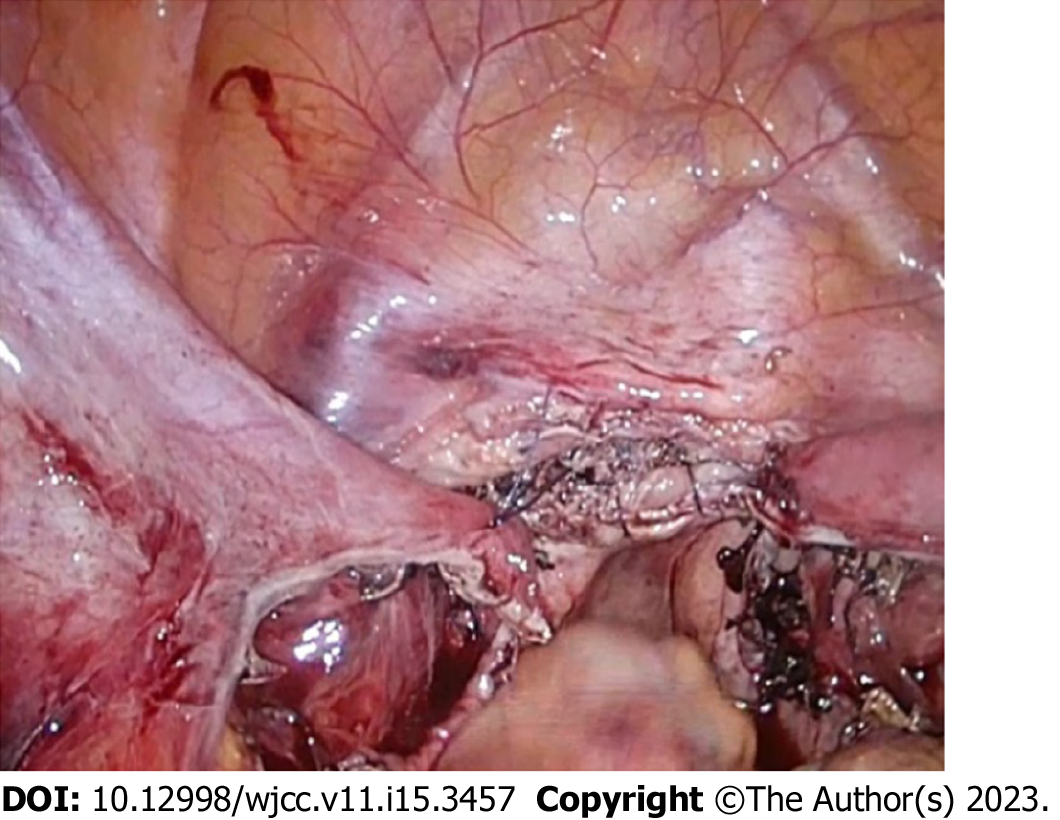

The Kakinuma method was performed with a pneumoperitoneum pressure of 10 mmHg using a 10-mm 0° rigid mirror in the lithotomy position with a 20° head-down tilt under general anesthesia. Using the open method, a trocar was placed using the modified diamond configuration, with a 12-mm camera port at the umbilical region and 5-mm ports at three sites in the lower abdomen. The surgical trocar was positioned 3 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spines and their midpoints. After incising the vesicouterine pouch, the round and ovarian suspensory ligaments were cut. After identifying the uterine artery and ureter, the main uterine artery trunk was ligated. The bladder was separated from the cervix, and the bilateral cardinal ligaments and parauterine tissues were ligated and cut. The vaginal canal was released from the posterior vaginal fornix, and the uterus was transvaginally removed after incising the vaginal canal circumferentially from the vaginal lumen along the vaginal portion of the cervix. The vaginal stump was closed by continuous suture with 1-0 absorbable thread after laparoscopically ligating both stumps with 1-0 absorbable thread. Then, the vaginal stump was continuously sutured to the round ligament on both sides by 2-0 delayed absorbable thread (Figure 1), and the vaginal stump was lifted (Figure 2).

In cases where the round ligaments were overextended, we resected the redundant round ligaments so that the vaginal stump was 4–5 cm from the vaginal opening. Next, the vaginal stump was lifted by suturing it to the round ligaments. After confirming no bleeding in the abdominal cavity, an anti-adhesion agent was sprayed, and the surgery was completed.

Background data for the 30 study patients are presented in Table 1. Numerical data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation. The mean age was 66.5 ± 9.1 (45-82) years, body mass index was 24.5 ± 3.3 (20.9-32.8) kg/m2, gravidity was 3.1 ± 1.4 (2-7), and parity was 2.5 ± 0.6 (2-4) times. According to the POP quantification stage classification, there were 8 patients with stage II, 11 with stage III, and 11 with stage IV. Surgical outcomes are shown in Table 2. The mean surgery duration was 113.4 ± 22.6 (88-148) min, the mean blood loss was 26.5 ± 39.7 (10-150) mL, and there were no perioperative complications. The mean follow-up period was 20.5 ± 6.8 (12-31) mo. No patients demonstrated recurrent POP.

| Feature | Value |

| Age in yr | 66.5 ± 9.1 |

| Body mass index in kg/m2 | 24.5 ± 3.3 |

| Gravidity, times | 3.1 ± 1.4 |

| Parity, times | 2.5 ± 0.6 |

| POP-Q stage, n cases | |

| I | 0 |

| II | 8 |

| III | 11 |

| IV | 11 |

| Outcome | Value |

| Surgical duration in min | 113.4 ± 22.6 |

| Blood loss in mL | 26.5 ± 39.7 |

| Surgical complications | None |

| Postoperative follow-up period in mo | 20.5 ± 6.8 |

| Recurrent cases | None |

This study examined the usefulness and safety of a new repair technique using patients’ own tissues (NTR) for POP, a general term for conditions such as urethrocele, cystocele, uterine prolapse, enterocele, and rectocele according to the site of prolapse. POP treatment aims to relieve symptoms by anatomically restoring the abnormal positioning of these prolapsed organs. Conservative therapies for POP include physical methods, such as pelvic floor exercises, and noninvasive repair methods using a pessary. For patients with organ prolapses of moderate or severe POP, surgery is the preferred treatment[5,6].

Patients with more severe POP tend to be older. Consequently, each patient’s general medical status and social background must be considered when selecting the surgical technique. In Japan, total hysterectomy and colporrhaphy have been used as traditional surgical therapies. However, it is difficult to treat POP with only suture repair by cutting off surplus mucosa of the vaginal wall. The recurrence rate is high and does not constitute a radical treatment in many cases. In 2004, transvaginal mesh surgery that replaced pubic cervical and rectal vaginal fascia, the most important pelvic floor support, with mesh was reported[14] and became widely popular. However, since approximately 2006, complications such as mesh exposure and incision wound erosion have been reported, and the Food and Drug Administration has issued an alert against it[11].

On the contrary, an abdominal technique that lifts the vaginal stump to the promontory was reported in 1957. Abdominal sacral fixation emerged with the subsequent popularization of mesh; however, the highly invasive nature of the surgery and intraoperative complications, such as major bleeding from the sacrum, limited its popularity[15,16]. However, laparoscopic surgery has also been covered by national health insurance since April 2014 in Japan, with the development of laparoscopic technology. Despite its less invasive nature, LSC produces treatment effects equivalent to laparotomy[17]; consequently, the popularity of this method has continued to grow. However, this surgery still uses mesh. As described above, concerns remain about complications associated with foreign objects. In addition, this surgical technique retains the cervix following upper cervical amputation. This necessitates regular postoperative cervical cancer examinations that decrease a patient’s QOL.

These considerations have led some surgeons to revisit NTR, a conventional technique that does not employ mesh[18,19]. Standard NTR is based on the vaginal technique, and vaginal stump fixation is performed after a total hysterectomy. Vaginal stump fixation can be achieved using the Shull method, which fixes it to the uterosacral ligaments. The usefulness of the Shull method has been reported in recent years[12]. This method is characterized by lifting the vaginal canal in the physiological direction; however, it involves the risk of ureter injury because of its proximity to the uterosacral ligaments.

Some patients with severe POP also demonstrate long vaginal canals and overextended uterosacral ligaments. Consequently, effective repair may not be possible using conventional techniques that fix only the vaginal stump and uterosacral ligaments.

To address these limitations, we developed a novel, modified form of NTR technique that anyone can perform. Herein, we describe the laparoscopic vaginal stump–round ligament fixation method (Kakinuma method) that can fix the vaginal stump to the round ligaments after a total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Anatomically, the round ligaments reside in a higher position in the body, are strong, and have no proximal important organs.

Historically, POP surgery was performed transvaginally. However, establishing an adequate visual field using this method is difficult. Laparoscopic surgery allows for sharing a clear, magnified visual field and is useful for training. Recently, total laparoscopic hysterectomy has become a basic surgical technique for obstetricians and gynecologists that does not require special surgical equipment and tools. There are no important organs around round ligaments anatomically. Therefore, the surgical technique is not particularly difficult and is minimally influenced by surgeons’ skills. We observed no surgery-related complications among our patients. In addition, for patients with overextended round ligaments, sufficient vaginal stump lifting is possible by fixing the vaginal stump after partially removing the round ligaments. This positions the vaginal stump 4-5 cm from the vaginal opening.

This study recruited patients who could be followed up for more than 12 mo after surgery, and there were no reported instances of POP recurrence. However, long-term outcomes remain unclear. We are collecting additional cases over a longer follow-up period to fill this knowledge gap. Future studies should compare the Kakinuma method to other LSC methods that use mesh and evaluate recurrence-related factors. Additionally, future studies should examine outcomes such as recurrence rate, recurrence time, and POP quantification stages in recurrent cases. Countermeasures used to treat POP recurrence should also be examined.

The limited number of examined cases is a limitation of this study. Future efficacy and safety examinations of the Kakinuma method will be needed, and additional cases with longer-term follow-ups are required. We are currently working on comparing the Kakinuma method with other NTR-based repair strategies for patients with moderate-to-severe POP.

The novel Kakinuma method safely and effectively lifts the vaginal stump to an anatomically higher position. It may be an effective surgical treatment for POP, similar to conventional NTR, and can be used successfully in patients unable to tolerate conventional NTR approaches.

Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) had been gaining popularity as a new approach. However, since the United States Food and Drug Administration alert against the use of mesh, native tissue repair (NTR) using the patient’s own tissue without mesh has gained attention.

Vaginal stump sacral uterine ligament fixation (Shull method) is a feasible surgical procedure for NTR with good results. However, in severe POP, the length of the vaginal canal and overstretching of the sacral uterine ligament may prevent effective repair by simply fixing the vaginal stump and sacral uterine ligament.

To solve this problem, an operation to fix the vaginal stump to the round ligament, which is a histologically tough tissue that is anatomically higher than the sacral uterine ligament, is performed laparoscopically; thus, inferior vaginal stump–round ligament fixation (the Kakinuma method) was devised. This study aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of the Kakinuma method in POP.

From January 2020 to December 2021, 30 patients who underwent the Kakinuma method for POP were examined, and the operative time, bleeding amount, recurrence rate, etc were investigated.

The average age was 66.5 ± 9.1 years, the number of deliveries was 2.5 ± 0.6, body mass index was 24.5 ± 3.3, and the POP quantification stage classification was stage II in 8 cases, stage III in 11, and stage IV in 11. The average operating time was 113.4 ± 22.6 min, the average blood loss was 26.5 ± 39.7 mL, there were no perioperative complications, and no cases of POP recurrence were observed.

The Kakinuma method in POP could be a safe and effective treatment similar to conventional NTR.

Future studies including more patients should examine outcomes such as recurrence rate, recurrence time, and POP quantification stages in recurrent cases. We are currently comparing the Kakinuma method with other NTR-based repair strategies for patients with moderate-to-severe POP.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: He Z, China; Hegazy AA, Egypt; Martín Del Olmo JC, Spain; Samara AA, Greece S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Samuelsson EC, Victor FT, Tibblin G, Svärdsudd KF. Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:299-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 482] [Cited by in RCA: 422] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2505] [Cited by in RCA: 2324] [Article Influence: 83.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fialkow MF, Newton KM, Lentz GM, Weiss NS. Lifetime risk of surgical management for pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:437-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Jonsson Funk M. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1201-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 605] [Cited by in RCA: 765] [Article Influence: 69.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Iglesia CB, Smithling KR. Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96:179-185. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Weintraub AY, Glinter H, Marcus-Braun N. Narrative review of the epidemiology, diagnosis and pathophysiology of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Braz J Urol. 2020;46:5-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hagen S, Stark D. Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD003882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | de Albuquerque Coelho SC, de Castro EB, Juliato CR. Female pelvic organ prolapse using pessaries: systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27:1797-1803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Doaee M, Moradi-Lakeh M, Nourmohammadi A, Razavi-Ratki SK, Nojomi M. Management of pelvic organ prolapse and quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:153-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Auwad W, Bombieri L, Adekanmi O, Waterfield M, Freeman R. The development of pelvic organ prolapse after colposuspension: a prospective, long-term follow-up study on the prevalence and predisposing factors. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:389-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA takes action to protect women’s health, orders manufacturers of surgical mesh intended for transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse to stop selling all devices. Apr 16, 2019. [cited 28 Dec 2022]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-action-protect-womens-health-orders-manufacturers-surgical-mesh-intended-transvaginal. |

| 12. | Shull BL, Bachofen C, Coates KW, Kuehl TJ. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1365-73; discussion 1373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 313] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bellier A, Cavalié G, Marnas G, Chaffanjon P. The round ligament of the uterus: Questioning its distal insertion. Morphologie. 2018;102:55-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Debodinance P, Berrocal J, Clavé H, Cosson M, Garbin O, Jacquetin B, Rosenthal C, Salet-Lizée D, Villet R. [Changing attitudes on the surgical treatment of urogenital prolapse: birth of the tension-free vaginal mesh]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2004;33:577-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gadonneix P, Ercoli A, Scambia G, Villet R. The use of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy in the management of pelvic organ prolapse. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;17:376-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Coolen AWM, van Oudheusden AMJ, Mol BWJ, van Eijndhoven HWF, Roovers JWR, Bongers MY. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy compared with open abdominal sacrocolpopexy for vault prolapse repair: a randomised controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28:1469-1479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Freeman RM, Pantazis K, Thomson A, Frappell J, Bombieri L, Moran P, Slack M, Scott P, Waterfield M. A randomised controlled trial of abdominal vs laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for the treatment of post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse: LAS study. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:377-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sassani JC, Artsen AM, Moalli PA, Bradley MS. Temporal Trends of Urogynecologic Mesh Reports to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1084-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Braga A, Serati M, Salvatore S, Torella M, Pasqualetti R, Papadia A, Caccia G. Update in native tissue vaginal vault prolapse repair. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31:2003-2010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |