Published online Apr 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i12.2832

Peer-review started: December 30, 2022

First decision: February 2, 2023

Revised: February 7, 2023

Accepted: March 30, 2023

Article in press: March 30, 2023

Published online: April 26, 2023

Processing time: 116 Days and 14.7 Hours

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is a global problem, causing significant morbidity and mortality. Furazolidone is recommended to eradicate H. pylori infections in China owing to the highly associated antibiotic resistance.

This article presents two cases of lung injury caused by furazolidone treatment of H. pylori infection and the relevant literature review. Two patients developed symptoms, including fever, cough, and fatigue after receiving a course of furazolidone for H. pylori infection. Chest computed tomography showed bilateral interstitial infiltrates. Laboratory studies revealed elevated blood eosinophil count. After discontinuing furazolidone with or without the use of corticosteroids, the symptoms improved rapidly. A PubMed database literature search revealed three reported cases of lung injury suggestive of furazolidone-induced pulmonary toxicity.

Clinicians should be aware of the side effects associated with the administration of furazolidone to eradicate H. pylori infection.

Core Tip: Furazolidone should be used as a treatment option for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication in China because of high antibiotic resistance. We present two cases of furazolidone-induced pulmonary hypersensitivity determined by the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale score. Clinicians should be aware of the adverse effects of furazolidone, especially as it is widely used in the treatment of H. pylori infection in China.

- Citation: Ye Y, Shi ZL, Ren ZC, Sun YL. Furazolidone-induced pulmonary toxicity in Helicobacter pylori infection: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(12): 2832-2838

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i12/2832.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i12.2832

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is highly prevalent worldwide and is the leading cause of gastritis, peptic ulcers, and gastric cancer[1]. H. pylori remains the most common human bacterial pathogen, infecting approximately half of the global population[2]. The overall H. pylori infection rate has declined gradually over the past 3–4 years owing to ongoing interventions, education, improved sanitation, and water quality. However, the incidence was high (46.7%) between 2006 and 2018[3]. The most commonly recommended therapy worldwide is a standard dose of proton-pump inhibitor (PPI)-based regimen consisting of a PPI, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and/or metronidazole[4]. However, the eradication rate of standard therapy is less than 80%, with the increasing drug resistance of H. pylori[5]. Furazolidone, a conventional drug administered for decades in the developing countries to eradicate H. pylori infections, has low resistance rates[6]. The Fifth Chinese National Consensus Report recommended the administration of furazolidone as a treatment option for H. pylori eradication in China because of its high antibiotic resistance[7].

The side effects of furazolidone are mild and well-tolerated by most patients[8]. Common furazolidone side effects include gastrointestinal reactions[4], including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and allergic reactions characterized by fever and rash[9]. Pulmonary hypersensitivity induced by furazolidone administration for the treatment of H. pylori infection is uncommon and rarely reported. Therefore, furazolidone-induced pulmonary toxicity goes largely unrecognized, prolonging diagnosis and leading to irreversible pulmonary complications.

Here, we present two cases of furazolidone-induced pulmonary hypersensitivity determined using the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale score (score: 11). Furthermore, we review the literature to improve our understanding of the side effects of furazolidone.

Case 1: Progressive fatigue and cough lasting 1 wk.

Case 2: A 1d history of fever and a mild cough.

Case 1: A 38-year-old woman presented at our hospital complaining of progressive fatigue and cough lasting 1 wk. There was no history of pyrexia, weight loss, night sweats, chest tightness, dyspnea, or rash.

Case 2: A 36-year-old woman presented with a 1-d history of fever and a mild cough. She did not complain of weight loss, night sweats, chest tightness, dyspnea, or rash.

Case 1: Her medical history revealed that she underwent cesarean section in 2017. Chronic non-atrophic gastritis caused by H. pylori infection was diagnosed 6 mo before her presentation. Eighteen days prior, she was prescribed rabeprazole (10 mg), potassium bismuth citrate (600 mg), amoxicillin (1 g), and furazolidone (100 mg) twice daily for 2 wk, to treat the H. pylori infection.

Case 2: Twelve days before her presentation, she was diagnosed with H. pylori infection and treated with omeprazole (20 mg), potassium bismuth citrate (600 mg), amoxicillin (1 g), and furazolidone (100) mg twice daily.

Case 1: Furthermore, the patient had never smoked and had no occupational exposure or a history of allergies.

Case 2: The patient had never smoked and denied alcohol consumption.

Case 1: Physical examination revealed the following vital signs: Temperature, 37 °C; heart rate, 95 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; blood pressure, 112/86 mmHg; and oxygen saturation, 98% in room air. Pulmonary examination revealed bilateral coarse breath sounds. Other physical examinations, including cardiac examinations, were unremarkable.

Case 2: Her vital signs at the outpatient clinic were as follows: Temperature, 38.5 ℃; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; heart rate, 80 beats/min; and blood pressure, 116/74 mmHg. Chest auscultation revealed bilateral coarse breath sounds, while the other general examination results were normal.

Case 1: Routine blood tests revealed an elevated eosinophil ratio (10.9%; reference range, 0.4%–8%) and blood eosinophil count (0.55 × 109/L; reference range, 0.02–0.52 × 109/L). We observed a rapid erythrocyte sedimentation rate (44 mm/h; reference range, 0–26 mm/h) and elevated immunoglobulin E (966 IU/mL; reference range, 0–87 IU/mL). The electrolyte panel, renal function, hepatic function, thyroid function, glucose level, tumor markers, and antinuclear antibodies were normal.

Case 2: Although the white blood cell and neutrophil counts were within the normal ranges, the eosinophil ratio (9.8%) and C-reactive protein (11.2 mg/L; reference range, 0–10 mg/L) were elevated. The electrolyte panel, renal function, hepatic function, and cardiac workup results were normal.

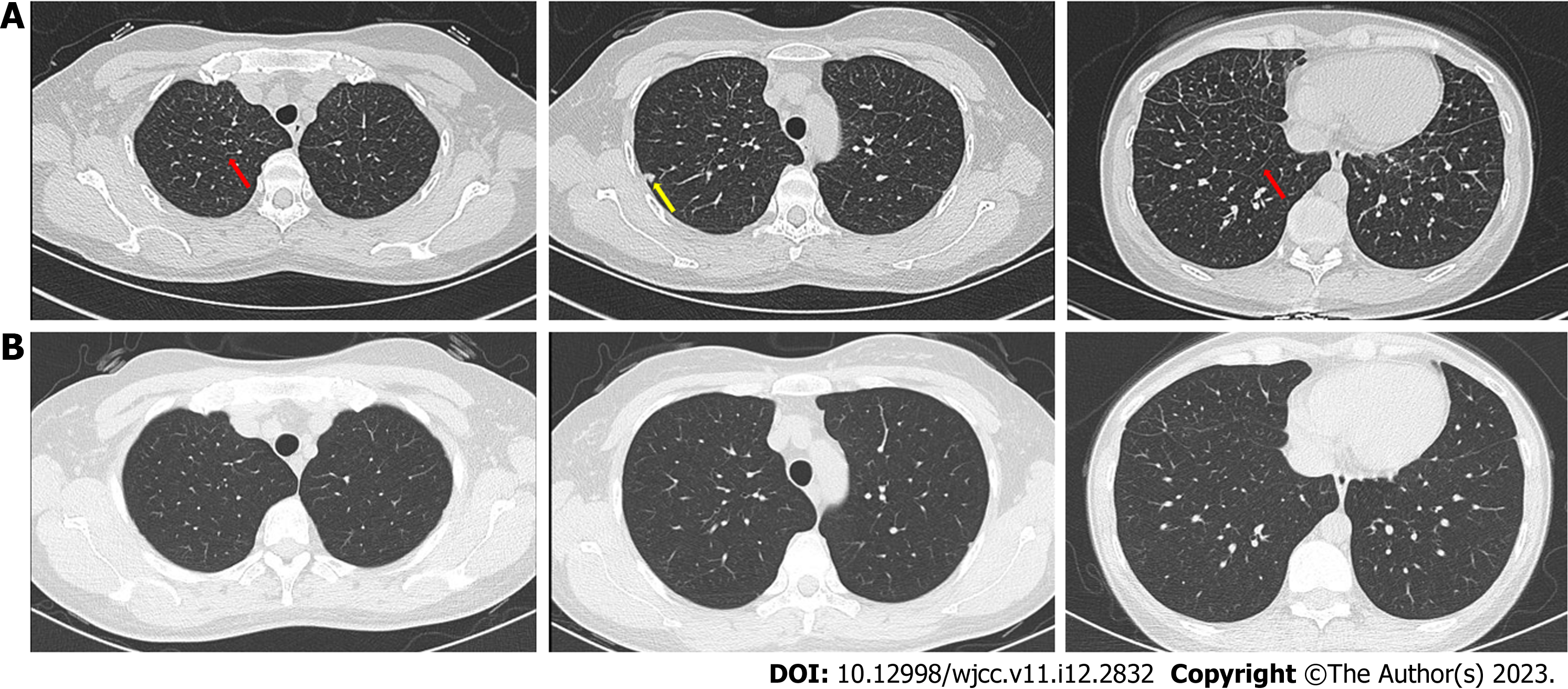

Case 1: Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed bilateral interstitial infiltrates, mainly manifested as interlobular septal thickening and nodules (Figure 1A).

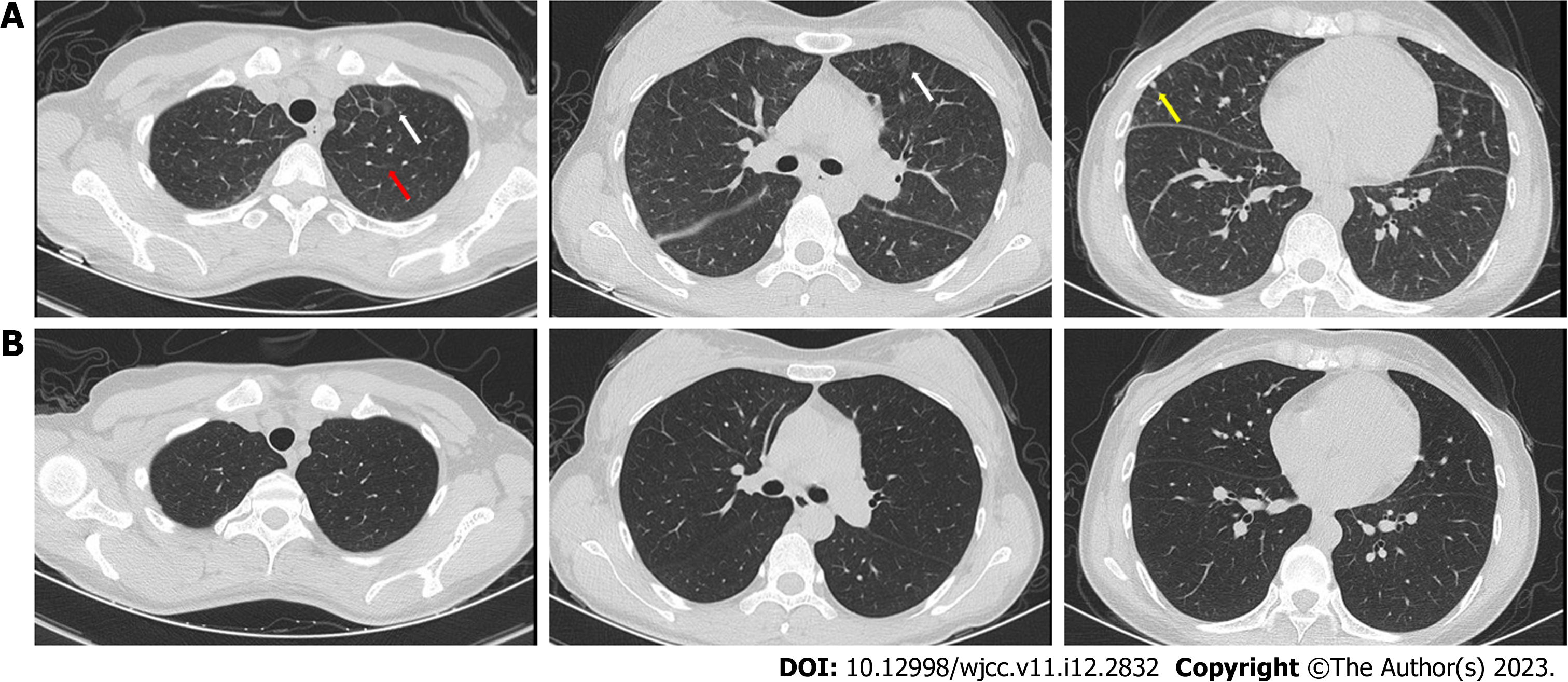

Case 2: Chest CT showed bilateral interstitial infiltrates, including patchy hyperdense foci, combined with thickening of the interlobular septa and nodules (Figure 2A).

The two patients were diagnosed with furazolidone-induced lung injury based on the findings.

For case 1, the patient received a 6 d treatment with intravenous prednisone (40 mg/d). Then the intravenous administration of prednisone was replaced with oral administration, and the dose was gradually reduced over a week. For case 2, due to the adamant refusal of oral corticosteroids administration and hospitalization, only furazolidone was discontinued, and antipyretic treatment was administered.

For case 1, the fatigue and cough rapidly subsided. The eosinophil ratio was 0.3%, and chest CT showed significant absorption of bilateral interstitial infiltrates (Figure 1B). The patient did not show any similar symptoms during the follow-up period. For case 2, the symptoms improved rapidly, and chest CT after 1 mo revealed obvious absorption of bilateral interstitial infiltrates (Figure 2B).

H. pylori infection is a family-based, population-wide disease that causes significant morbidity and mortality as it causes peptic ulcers and gastric cancer. It poses a major health threat to the Chinese families and society through increasing the economic and medical burden of the country[3]. In 2020, a meta-analysis, including 670572 participants from 26 provinces of mainland China, reported that the overall prevalence was 63.8% between 1983 and 1994, 57.5% between 1995 and 2005, and 46.7% between 2006 and 2018[10]. The infection rates vary greatly among different geographical regions and are much higher in the rural areas[10]. The discovery that H. pylori causes most duodenal ulcers and approximately two-thirds of gastric ulcers is seminal. Furthermore, H. pylori has been estimated to increase lifetime risk of gastric cancer by 1.5%–2.0%[11]. Previous studies reported that H. pylori eradication for gastric cancer prevention is cost-effective in China[12].

Optimal clinical management and treatment approaches are unknown and evolve in response to the changing antimicrobial resistance patterns[11]. In many parts of the world, triple therapy with PPI, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, or bismuth-based quadruple therapy with PPI, bismuth, tetracycline, and metronidazole, is the most commonly administered first-line treatment regimen[4]. In China, the rate of H. pylori resistance to antibiotics, including clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin, is increasing[7]. Recent studies reported that the resistance rates to clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin were 20%–50%, 40%–70%, and 20%–50%, respectively[13]. Furthermore, H. pylori can be resistant to multiple antibiotics[13]. Previous studies reported that the dual resistance of H. pylori to clarithromycin and metronidazole is approximately 25%[14]. Therefore, implementing these regimens in China may result in significantly lower eradication rates.

Furazolidone is a synthetic nitrofuran monoamine oxidase inhibitor with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity[15]. However, its therapeutic effect on H. pylori infection cannot be ignored. Currently, the resistance rates of H. pylori to furazolidone are low (0%–1%)[13]. Because it rarely produces resistance, it can be readministered after a treatment failure. Therefore, some national and regional guidelines for H. pylori infection recommend furazolidone as a component of rescue therapy[11]. However, furazolidone has been administered in a few high-quality eradication studies, and there is a lack in randomized trials. Additionally, concerns about its safety and use have resulted in its unavailability in the United States and European Union[4]. However, due to antibiotic resistance, it is recommended as empirical first-line therapy for H. pylori infection in China[7]. With the increasing use of furazolidone in China, its related side effects should be fully recognized and monitored.

The most common side effects of furazolidone are gastrointestinal reactions, including nausea and abdominal pain[4,15]. Furazolidone-related allergic reactions are clinically common and are characterized by fever (1.8%) and rash (0.3%)[10]. One study reported that rash and fever were the most frequent clinical findings in antibiotic-induced drug reactions, with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms[16]. Pulmonary hypersensitivity is uncommon; however, it often leads to fatal damage[16]. Drug-induced pulmonary hypersensitivity and interstitial lung disease may mediated by T cells; however, they are primarily affected by antibody-mediated factor functions (I–III)[17].

Following furazolidone treatment for H. pylori infection, the patients reported in this case report developed pulmonary hypersensitivity. The Naranjo probability score indicated that the adverse events could be drug-related. Using the search algorithm “furazolidone” and “pulmonary” or “lung”, we searched the PubMed database (as of May 2022). Three cases of pulmonary hypersensitivity were attributed to furazolidone; however, these included other bacterial infections. In all the reported patients, symptoms developed during or immediately after furazolidone administration, with prominent pyrexia and dyspnea (Table 1)[18-20]. Chest radiograph revealed bilateral interstitial infiltrates with subsequent eosinophilia.

| Ref. | Furazolidone administration time and dosage | Purpose of using furazolidone | Symptoms | Physical examination | Laboratory studies | Image test | Treatment |

| Cortez and Pankey[18], 1972 | A 4 d course, 100 mg twice daily | To prevent diarrhea | Fever, dyspnea, headache, and pleuritic chest pain | Dry, crackling rales | Eosinophils elevated | Diffuse, bilateral Infiltrates (X-ray) | 15 mg of prednisone orally followed by 40 mg daily |

| Collins and Thomas[19], 1973 | A 5 d course, dose not mentioned | To treat a gastrointestinal infection | Fever, rigors, generalized rash, breathless on slight exertion, and night sweats | No abnormal physical signs | Eosinophils and ESR elevated | Diffuse mottling (X-ray) | not mentioned |

| Kowalski et al[20], 2005 | A 10 d course, 125 mg 4 times daily | To treat Isospora Belli infection | Fever, dyspnea, and nonproductive cough | Bibasilar crackles | Eosinophil ratio elevated | Bilateral interstitial infiltrates (X-ray) | Prednisone 40 mg/day |

Our cases were similar to the three previously reported cases of furazolidone pulmonary hypersensitivity, with minor differences. Both patients developed symptoms during their furazolidone treatment. The three previously reported cases had severe symptoms, including significant pyrexia, dyspnea, and bibasilar crackles. The symptoms and physical signs in our cases were milder than those of the previous studies as there was no dyspnea or obvious crackles. This could be attributed to racial differences with respect to drug susceptibility or factors related to medication dosage and duration. However, the eosinophil levels were elevated during the early disease stages. Lung imaging revealed bilateral interstitial infiltrates. However, since only the radiographs of the patients have been shown in the past, the specific imaging findings of the chest CT are unknown. Both cases in our report showed interlobular septal thickening and nodules on the chest CT. Furthermore, the symptoms improved rapidly and significantly without recurrence after discontinuing furazolidone and the concurrent steroid administration.

This report highlights two rare cases of pulmonary hypersensitivity caused by furazolidone during treatment of H. pylori infection. Clinicians should be aware of the side effects of furazolidone, especially because it is widely used in China to treat H. pylori infection. The possibility of furazolidone-induced pulmonary hypersensitivity can be recognized based on the medical history, elevated eosinophil levels, and pulmonary interstitial infiltrates. Appropriate and timely treatment is required to prevent drug-induced damage.

The authors are grateful to the patients in this study for their collaboration.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gupta L, Indonesia; Kirkik D, Turkey; Sánchez JIA, Colombia S-Editor: Cai YX L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Crowe SE. Helicobacter pylori Infection. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1158-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 44.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, Malfertheiner P, Graham DY, Wong VWS, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:420-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1361] [Cited by in RCA: 2015] [Article Influence: 251.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ding SZ, Du YQ, Lu H, Wang WH, Cheng H, Chen SY, Chen MH, Chen WC, Chen Y, Fang JY, Gao HJ, Guo MZ, Han Y, Hou XH, Hu FL, Jiang B, Jiang HX, Lan CH, Li JN, Li Y, Li YQ, Liu J, Li YM, Lyu B, Lu YY, Miao YL, Nie YZ, Qian JM, Sheng JQ, Tang CW, Wang F, Wang HH, Wang JB, Wang JT, Wang JP, Wang XH, Wu KC, Xia XZ, Xie WF, Xie Y, Xu JM, Yang CQ, Yang GB, Yuan Y, Zeng ZR, Zhang BY, Zhang GY, Zhang GX, Zhang JZ, Zhang ZY, Zheng PY, Zhu Y, Zuo XL, Zhou LY, Lyu NH, Yang YS, Li ZS; National Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases (Shanghai), Gastrointestinal Early Cancer Prevention & Treatment Alliance of China (GECA), Helicobacter pylori Study Group of Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, and Chinese Alliance for Helicobacter pylori Study. Chinese Consensus Report on Family-Based Helicobacter pylori Infection Control and Management (2021 Edition). Gut. 2022;71:238-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhuge L, Wang Y, Wu S, Zhao RL, Li Z, Xie Y. Furazolidone treatment for Helicobacter Pylori infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2018;23:e12468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zheng Q, Chen WJ, Lu H, Sun QJ, Xiao SD. Comparison of the efficacy of triple vs quadruple therapy on the eradication of Helicobacter pylori and antibiotic resistance. J Dig Dis. 2010;11:313-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hu Y, Zhu Y, Lu NH. Primary Antibiotic Resistance of Helicobacter pylori in China. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1146-1154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Liu WZ, Xie Y, Lu H, Cheng H, Zeng ZR, Zhou LY, Chen Y, Wang JB, Du YQ, Lu NH; Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Study Group on Helicobacter pylori and Peptic Ulcer. Fifth Chinese National Consensus Report on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2018;23:e12475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 46.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zheng ZT, Wang YB. Treatment of peptic ulcer disease with furazolidone. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1992;7:533-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Buzás GM, Józan J. Nitrofuran-based regimens for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1571-1581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li M, Sun Y, Yang J, de Martel C, Charvat H, Clifford GM, Vaccarella S, Wang L. Time trends and other sources of variation in Helicobacter pylori infection in mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2020;25:e12729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | World gastroenterology organisation global guideline: Helicobacter pylori in developing countries. J Dig Dis. 2011;12:319-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen Q, Liang X, Long X, Yu L, Liu W, Lu H. Cost-effectiveness analysis of screen-and-treat strategy in asymptomatic Chinese for preventing Helicobacter pylori-associated diseases. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bai P, Zhou LY, Xiao XM, Luo Y, Ding Y. Susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori to antibiotics in Chinese patients. J Dig Dis. 2015;16:464-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhou L, Zhang J, Chen M, Hou X, Li Z, Song Z, He L, Lin S. A comparative study of sequential therapy and standard triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: a randomized multicenter trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:535-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Resina E, Gisbert JP. Rescue Therapy with Furazolidone in Patients with at Least Five Eradication Treatment Failures and Multi-Resistant H. pylori infection. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sharifzadeh S, Mohammadpour AH, Tavanaee A, Elyasi S. Antibacterial antibiotic-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome: a literature review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;77:275-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Matsuno O. Drug-induced interstitial lung disease: mechanisms and best diagnostic approaches. Respir Res. 2012;13:39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cortez LM, Pankey GA. Acute pulmonary hypersensitivity to furazolidone. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1972;105:823-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Collins JV, Thomas AL. Pulmonary reaction to furoxone. Postgrad Med J. 1973;49:518-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kowalski TJ, Henry MJ, Zlabek JA. Furazolidone-induced pulmonary hypersensitivity. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:377-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |