Published online Jan 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i1.201

Peer-review started: October 1, 2022

First decision: October 21, 2022

Revised: November 5, 2022

Accepted: December 21, 2022

Article in press: December 21, 2022

Published online: January 6, 2023

Processing time: 95 Days and 11.9 Hours

Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma (EES) is a rare and highly malignant small round cell tumor associated with a poor clinical outcome. Ewing sarcoma (ES) involving the stomach is an uncommon presentation and can be easily confused with other small round cell tumors. We herein present a rare case of ES involving the gastric area.

We report a case of gastric ES in a 19-year-old female patient who initially presented with a complaint of a tender epigastric mass for 5 d. Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography revealed a soft-tissue-density mass with a diameter of 8.5 cm between the liver and stomach; the mass was connected to the gastric antrum. Then, the mass was surgically excised completely. Upon histopathological, immunophenotype and molecular analysis, the mass was identified to be a primary gastric ES.

EES is an aggressive tumor with poor prognosis. Therefore, early diagnosis and timely intervention are essential for a good prognosis. It is imperative for us to raise awareness about this rare tumor. Surgical resection is still the best treatment option.

Core Tip: Ewing sarcoma (ES) is a rare and highly malignant small round cell tumor. Extraskeletal ES is more common in the paravertebral region, extremities, and retroperitoneum and very rarely occurs in the stomach. Due to its rarity, there are few studies on its clinicopathological characteristics and diagnostic protocols. It is an aggressive tumor with poor prognosis, and therefore, early diagnosis and timely intervention are vital for a good prognosis. Herein, we report on a case of primary gastric ES which was timely resected surgically. This was followed by chemotherapy, which was comprised of alternating vincristine–doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and ifosfamide–etoposide every 3 wk. Ultimately, the patient was tumor-free and achieved an excellent prognosis.

- Citation: Shu Q, Luo JN, Liu XL, Jing M, Mou TG, Xie F. Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma of the stomach: A rare case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(1): 201-209

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i1/201.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i1.201

Ewing sarcoma (ES) is a rare and highly malignant small round cell tumor[1]. It is characterized by different degrees of neuroectoderm differentiation and an EWSR1-ETS fusion protein[2]. ES often occurs in the pelvis, long axial bones, and the femur, whereas extraskeletal ES (EES) is more common in the paravertebral region, extremities, and the retroperitoneum[3]. It is very rare for EES to occur in the stomach. As reported in Hopp et al’s study, the incidence of EES accounted for 15%-20% of all ES cases[4]. Among the 70 EES cases reported by Huh, only 4 cases (5.7%) were of primary gastric ES[5]. Due to its rarity, there are few studies on its clinicopathological characteristics and diagnostic protocols. We herein report a case of primary gastric ES to raise awareness about this rare tumor for clinicians and radiologists.

A 19-year-old female patient presented with a complaint of a tender epigastric mass for 5 d.

Five days ago, the patient was admitted for a complaint of a tender epigastric mass. There was no prior history of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms or black stools, and she recently reported upper abdominal fullness after intake of little food.

The patient had no history of past illness.

No personal or family history was available.

On clinical examination, slight tenderness and an immovable mass in the right upper abdomen were identified.

Serum fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, squamous cell carcinoma antigen, neuron-specific enolase, carbohydrate antigen 125, carbohydrate antigen 153, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 were all normal.

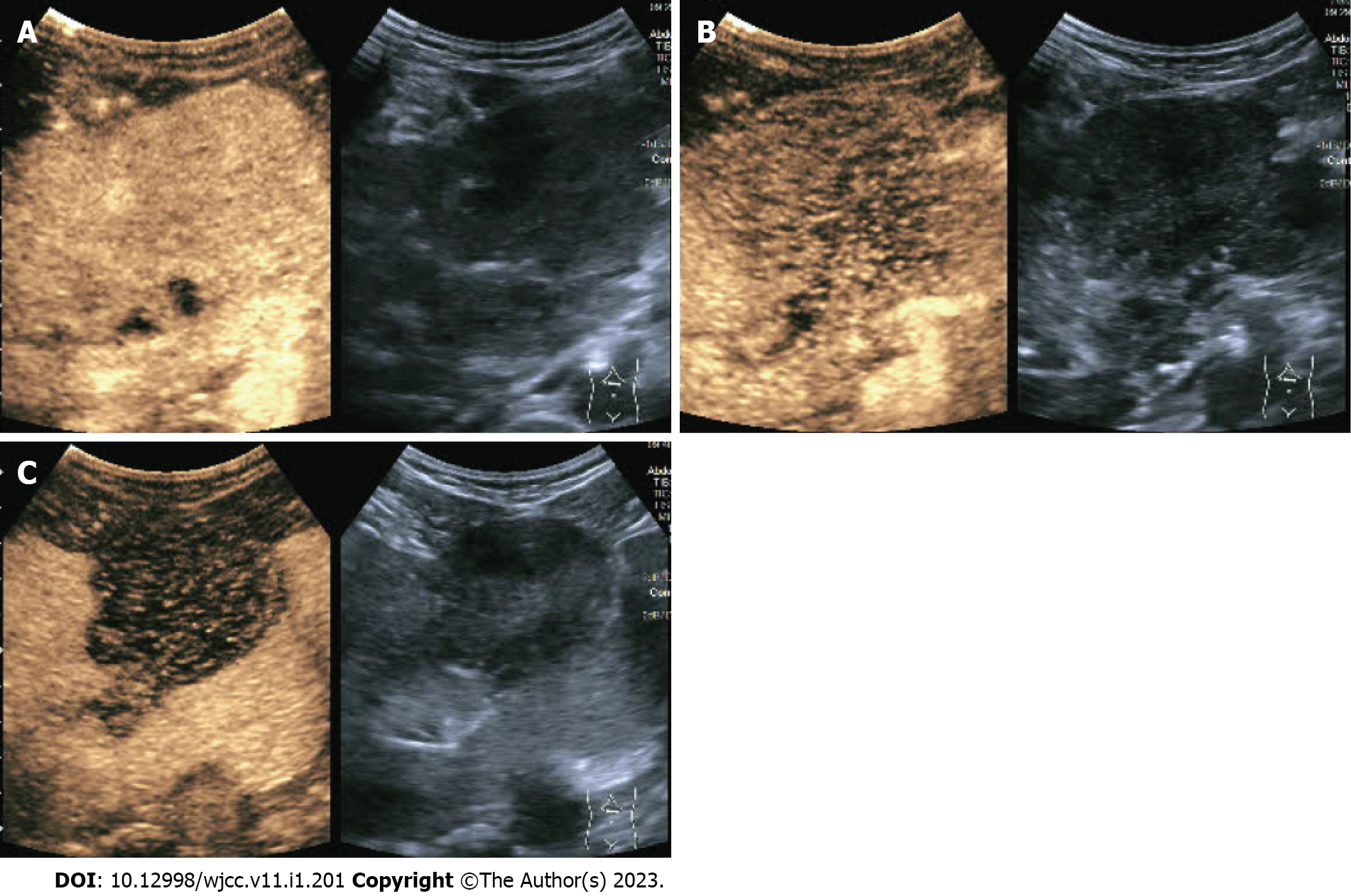

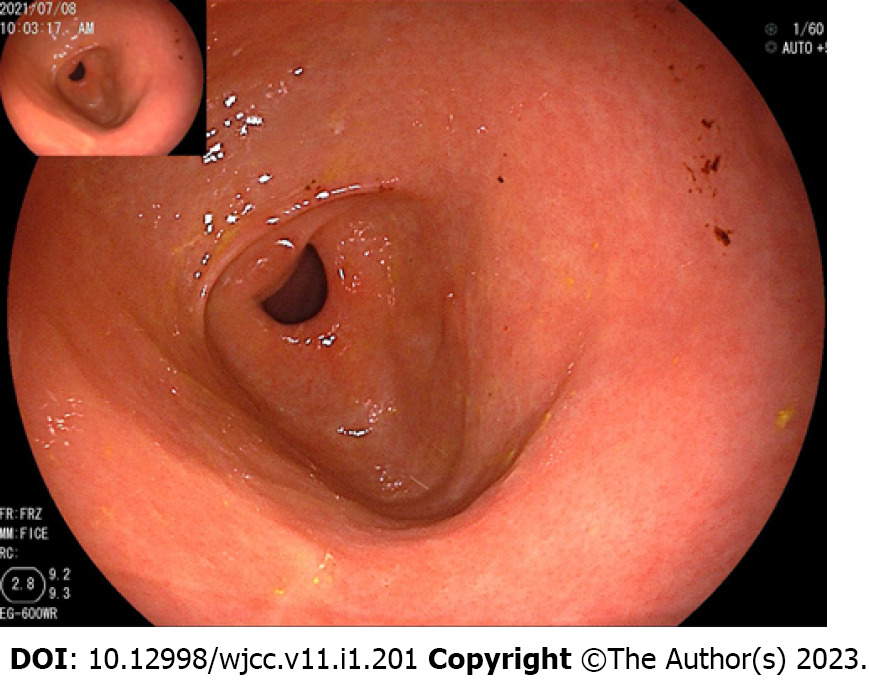

The abdominal contrast-enhanced ultrasound revealed a hypoechoic mass with a diameter of 8.5 cm between the liver and stomach. It had poorly defined boundaries and an irregular shape and mutual continuity with the gastric antrum. The pancreas was compressed by the mass, and a branch of the celiac trunk was seen to extend into the center of the mass. The ultrasound contrast agent SonoVue (12 mL) was injected through the cubital vein, and the mass and liver parenchyma showed synchronous homogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase; conversely, the mass showed non-homogeneous enhancement in the portal vein phase and slightly non-homogeneous enhancement in the hepatic delay phase. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound indicated a gastric stromal tumor (Figure 1). Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a soft-tissue-density mass measuring 8.5 cm in diameter between the liver and stomach. The mass had uneven internal density, mild continuous enhancement in the arterial phase, and blood supply from a small branch of the gastroduodenal artery. Furthermore, the mass was connected with the gastric antrum. There were no clearly enlarged lymph nodes in the abdominal cavity or retroperitoneum. Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT indicates a gastric antrum tumor (Figure 2). Subsequent esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed that the gastric antrum mucosa was intact and smooth (Figure 3). Chest CT and bone scan emission CT showed no abnormal findings.

According to the above history and the related imaging examination, the final diagnosis was of an abdominal tumor potentially of a gastric origin.

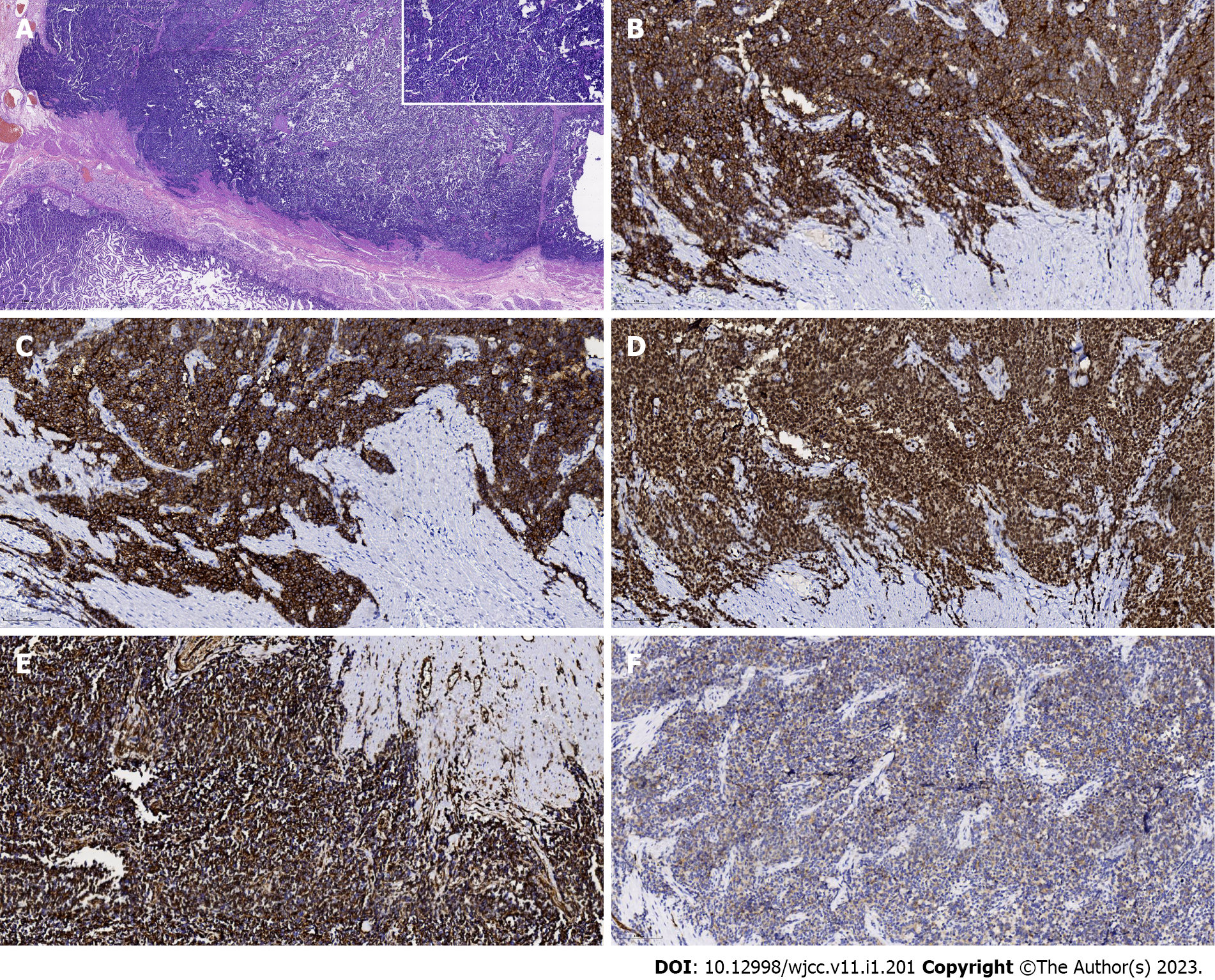

The patient underwent distal subtotal gastrectomy, gastroenterostomy, intestinal anastomosis, and regional lymphadenectomy. The resected specimen contained a firm, round tumor with extraluminal growth. It was located in the gastric antrum and measured 8.5 cm × 5.0 cm. Histological examination revealed that the tumor developed from the serous layer of the stomach and involved the muscularis externa of the stomach (Figure 4A). Tumor cells were characterized by uniform, compact, round-to-oval nuclei, a modest amount of pale eosinophilic cytoplasm, and pseudorosette formation. There were punctate areas of necrosis, but the degree of necrosis was less than seen in usual small-cell carcinoma; atypical mitoses were occasionally observed (Figure 4A). No metastatic tumors were found in the regional lymph nodes. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells were found to strongly express CD99 on the membrane and in the cytoplasm, vimentin in the cytoplasm, Fli-1 in the nuclei, and NSE and SYN in the cytoplasm (Figure 4B-F). Molecular analysis using fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed the EWS-FLI1 gene translocation t(11; 22) (q24; q12). Therefore, the tumor was eventually determined to be primary gastric ES. The patient recovered and was discharged from the hospital. Two months after the surgery, she underwent chemotherapy which was comprised of alternating vincristine–doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and ifosfamide–etoposide every 3 wk.

Ultimately, the patient was tumor-free and achieved an excellent prognosis. At the time of writing this paper, she was still alive and undergoing her tenth round of chemotherapy, and she showed no sign of a relapse 11 mo after the surgery (Figure 5).

ES is a highly malignant and small round cell tumor. It comprises classic ES of the bone, EES, and peripheral PNETs of the bone and soft tissue[1]. Primary gastric ES is exceptionally rare. Czekalla et al[6] first reported a case of gastric ES in 2004, and few cases have been reported in the literature so far. We summarize the reported cases of primary gastric ES in Table 1, describing their clinical presentation, immunohistochemistry findings, treatment and outcome[1,4,6-15]. The rare occurrence of EES in the stomach may be related to its origin from primitive tumor cells. Although the histogenesis of ES is unclear, it is well known that the most common chromosomal rearrangement in ES is a translocation between chromosomes 11 and 22 [t(11;22) (q24; q12)], which can result in new EWSR1-ETS fusion proteins as transcription factors that regulate the target genes, consequently leading to cell transformation and generation of tumors with ES morphology and gene expression characteristics[16]. By projecting t(11; 22) (q24; Q12) translocation, Sole et al[17] generated a large number of immortalized cells (EWIma cells) resistant to EWSR1-FLI1 expression from primary mesenchymal stem cells; these cells induced tumors and metastases in mice, suggesting that ES originates from human bone marrow primitive mesenchymal cells. Therefore, embryonic stem cell tumor cells of ES are possibly derived from primitive mesenchymal cells and possess limited neural differentiation potential[18,19]. This explains why they are typically located in the bone, peripheral nerves, and soft tissue[20].

| Ref. | Age in yr, sex | Clinical presentation | Location | Tumor size in cm | Immunohistochemistry | Molecular genetic detection | Distant metastasis | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | Surgery | Postoperative chemotherapy | Follow-up in mo | Outcome |

| Czekalla et al[6], 2004 | 14, M | Anorexia, epigastric pain | Anterior wall body | 5 | CD99, CD117, S100, vimentin, neurofilament, NSE | t(11;22)(q24;q12) | Liver | Yes | SG | No | 24 | Alive |

| Soulard et al[7], 2005 | 66, F | Epigastric pain | Antrum | 8 | CD99, S100, NSE, vimentin | t(21;22)(q22;q12) | No | No | Gastrectomy | Yes | 10 | Dead |

| Colovic et al[8], 2009 | 44, F | Epigastric pain | Posterior wall body | 10 | CD99, S100, vimentin, NSE, PGP9.5 | NA | No | No | Excision | No | 20 | Alive |

| Rafailidis et al[9], 2009 | 68, M | Abdominal pain, dyspepsia, weakness | Body | 12 | vimentin, NSE, CD99, CD117, Leu-7 | t(11;22)(q24;q12) | Liver | No | SG | Yes | 13 | Dead |

| Inoue et al[10], 2011 | 41, F | Abdominal pain | Anterior wall body | 9 | CD99, vimentin, CD117, S100, chromogranin A, synaptophysin | t(11;22)(q24;q12) | Enterocoelia | No | DG | Yes | 110 | Dead |

| Kim et al[11], 2012 | 35, F | No special symptoms | Antrum | 5.5 | CD99, synaptophysin | NA | No | No | WR | No | 11 | Alive |

| Song et al[12], 2016 | 55, M | Upper abdominal pain | vomiting High body | 6.5 | CD99, FLI1, chromogranin | EWS-FLI1 fusion transcript | Lymph nodes | No | TG | Yes | 13 | Alive |

| Kumar et al[13], 2016 | 32, F | Epigastric pain | Lesser curvature | 11 | CD99, vimentin, S100 | NA | No | No | Excision | Yes | 12 | Alive |

| Khuri et al[14], 2016 | 31, F | Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage | Lesser curvature | 11 | CD99, FLI1, vimentin, Ki67 | (11;22 translocation) | Pancreas Splenic hilum | No | TDPSLA | No | 36 | Alive |

| Maxwell et al[15], 2016 | 66, F | Anemia, abdominal pain | Antrum | 11 | NA | EWSR1 gene rearrangement | No | No | DG | Yes | NA | NA |

| Hopp et al[4], 2019 | 24, M | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting | Posterior wall | 10 | keratin OSCAR/ AE1/AE3, CD99 | NA | NA | Yes | DG | NA | NA | NA |

| Ye et al[1], 2021 | 55, M | fatigue and fever, lose weight | posterior wall | 7.5 | CD99, CD57, CD56, vimentin | NA | No | No | DG + Roux-en-Y | No | 8 | Alive |

EES grows slowly, and the mass diameter can exceed 20 cm; however, patients often do not exhibit any evident clinical symptoms[21]. Ye et al[1] summarized 12 cases of primary gastric ES and found that it tends to occur more often in women, has nonspecific clinical manifestations, and predominantly presents as single tumors larger than 5 cm in diameter. Therefore, primary gastric ES is difficult to detect and diagnose early. In our patient, the clinical manifestations were nonspecific, and she was admitted to the hospital for further examination because she inadvertently palpated and identified an abdominal mass, which was eventually found to be an abdominal tumor.

Clinical examination, imaging, and histology are nonspecific in evaluating rare tumors and distinguishing them from other solid masses. The imaging features of EES are nonspecific, with fluoro-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT showing hypermetabolic lesions and CT/Magnetic resonance imaging typically showing an enhanced, bulky, soft-tissue lesion with internal heterogeneity if the tumor grows sufficiently large, secondary to ulceration, hemorrhage, and/or necrosis[1,4]. Calcification has been reported in up to 25% of cases[4]. On ultrasonography, EES usually appears as a low-echogenicity heterogeneous mass with intratumoral blood flow signals[22]. Owing to radiographic similarities, EES in abdominal and pelvic cavities may be frequently mistaken for gists[5], which was also the case in the preoperative imaging examination of this patient.

Pathological diagnosis is the gold standard for EES diagnosis. Histologically, ES presents with undifferentiated uniform small round cells, absence of nucleoli, a finely granular chromatin pattern, and a scanty cytoplasm with varying degrees of neuroectodermal differentiation[23]. Therefore, EES diagnosis relies on a constellation of immunohistochemical features as there is no pathognomonic marker, and these features include round cell morphology and characteristic immunohistochemistry findings, such as CD99, FLI-1, vimentin, NKX2, ERG, NSE, Leu-7, and SYN positivity[24,25].

CD99 is a single-chain type-1 glycoprotein that is highly sensitive but not specific, and its presence can be noted in a lot of other neoplastic conditions[23,24,26]. FLI-1 has recently been discovered as a DNA-binding transcription factor involved in t(11;22) translocation; although FLI-1 immunohistochemistry is typically positive in ES (about 75% of cases), it is also nonspecific and can occur in mucosal melanoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma[24,26]. Immunohistochemical studies may include an epithelial marker (pancytokeratin, such as CKAE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen, or OSCAR), a neuroendocrine marker (synaptophysin), a muscle marker (desmin, myogenin, or MYOD1), and S100 (to exclude melanoma)[26]. For patients suspected as having EES, fluorescence in situ hybridization is necessary to confirm the pathognomonic molecular abnormalities of t(11;22) (q24; q12)[24,25].

There is no unified standard for the treatment of EES. Currently, surgical resection and chemoradiotherapy are the most widely used treatments[25]. In our patient, the tumor lesion was relatively isolated and had not spread to the abdominopelvic cavity, thus allowing for its complete excision. ES is a radiosensitive tumor, and isolated radiotherapy can be used as a local treatment. Both ES and EES possess the EWSR1–ETS fusion protein and belong to the ES family. Therefore, EES is similarly sensitive to radiotherapy. When it is not possible to obtain wide margins because of the presence of fixed structures, such as vessels and/or nerves, postoperative radiotherapy can be implemented for better local control[27]. Accordingly, event-free survival at 5 years was better when surgery was followed by radiotherapy (70%) compared to only surgery (59%)[28]. However, our patient refused to undergo radiation therapy after radical surgery. Two months after the surgery, she underwent chemotherapy which comprised alternating cyclophosphamide, vincristine–doxorubicin, and ifosfamide–etoposide every 3 wk. At the time of the writing of this report, she is alive and shows no signs of recurrence 11 mo after the operation.

Taken together, primary gastric ES is difficult to diagnose early because of its rarity and nonspecific symptoms, signs, and imaging features. We believe this rare case is of importance for clinicians and radiologists to enhance their awareness of early identification and diagnosis of this type of tumor.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Elpek GO, Turkey; Kumar S, India; Musoni L, Morocco S-Editor: Chang KL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Chang KL

| 1. | Ye Y, Qiu X, Mei J, He D, Zou A. Primary gastric Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:300060520986681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Lewis TB, Coffin CM, Bernard PS. Differentiating Ewing's sarcoma from other round blue cell tumors using a RT-PCR translocation panel on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:397-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Brasme JF, Chalumeau M, Oberlin O, Valteau-Couanet D, Gaspar N. Time to diagnosis of Ewing tumors in children and adolescents is not associated with metastasis or survival: a prospective multicenter study of 436 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1935-1940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hopp AC, Nguyen BD. Gastrointestinal: Multi-modality imaging of extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma of the stomach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Huh J, Kim KW, Park SJ, Kim HJ, Lee JS, Ha HK, Tirumani SH, Ramaiya NH. Imaging Features of Primary Tumors and Metastatic Patterns of the Extraskeletal Ewing Sarcoma Family of Tumors in Adults: A 17-Year Experience at a Single Institution. Korean J Radiol. 2015;16:783-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Czekalla R, Fuchs M, Stölzle A, Nerlich A, Poremba C, Schaefer KL, Weirich G, Höfler H, Schneller F, Peschel C, Siewert JR, Schepp W. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the stomach in a 14-year-old boy: a case report. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1391-1400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Soulard R, Claude V, Camparo P, Dufau JP, Saint-Blancard P, Gros P. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the stomach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:107-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Colovic RB, Grubor NM, Micev MT, Matic SV, Atkinson HD, Latincic SM. Perigastric extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:245-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rafailidis S, Ballas K, Psarras K, Pavlidis T, Symeonidis N, Marakis G, Sakadamis A. Primary Ewing sarcoma of the stomach--a newly described entity. Eur Surg Res. 2009;42:17-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Inoue M, Wakai T, Korita PV, Sakata J, Kurosaki R, Ogose A, Kawashima H, Shirai Y, Ajioka Y, Hatakeyama K. Gastric Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2011;2:207-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim HS, Kim S, Min YD, Kee KH, Hong R. Ewing's Sarcoma of the Stomach; Rare Case of Ewing's Sarcoma and Suggestion of New Treatment Strategy. J Gastric Cancer. 2012;12:258-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Song MJ, An S, Lee SS, Kim BS, Kim J. Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor of the Stomach: A Case Report. Int J Surg Pathol. 2016;24:543-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kumar D. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma /primitive neuroectodermal tumor of stomach. Tropical Gastroenterology. 2016;37. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Khuri S, Gilshtein H, Sayidaa S, Bishara B, Kluger Y. Primary Ewing Sarcoma/Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor of the Stomach. Case Rep Oncol. 2016;9:666-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Maxwell AW, Wood S, Dupuy DE. Primary extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma of the stomach: a rare disease in an uncommon location. Clin Imaging. 2016;40:843-845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Castillero-Trejo Y, Eliazer S, Xiang L, Richardson JA, Ilaria RL Jr. Expression of the EWS/FLI-1 oncogene in murine primary bone-derived cells Results in EWS/FLI-1-dependent, ewing sarcoma-like tumors. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8698-8705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sole A, Grossetête S, Heintzé M, Babin L, Zaïdi S, Revy P, Renouf B, De Cian A, Giovannangeli C, Pierre-Eugène C, Janoueix-Lerosey I, Couronné L, Kaltenbach S, Tomishima M, Jasin M, Grünewald TGP, Delattre O, Surdez D, Brunet E. Unraveling Ewing Sarcoma Tumorigenesis Originating from Patient-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Cancer Research. 2021;81:4994-5006. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Riggi N, Cironi L, Provero P, Suvà ML, Kaloulis K, Garcia-Echeverria C, Hoffmann F, Trumpp A, Stamenkovic I. Development of Ewing's sarcoma from primary bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11459-11468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tirode F, Laud-Duval K, Prieur A, Delorme B, Charbord P, Delattre O. Mesenchymal stem cell features of Ewing tumors. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:421-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Tsokos M, Alaggio RD, Dehner LP, Dickman PS. Ewing sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor and related tumors. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2012;15:108-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nissim L, Mandell G. Gastric Ewing Sarcoma identified on a Meckel's scan. Radiol Case Rep. 2020;15:1235-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Abboud A, Masrouha K, Saliba M, Haidar R, Saab R, Khoury N, Tawil A, Saghieh S. Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma: Diagnosis, management and prognosis. Oncol Lett. 2021;21:354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn P, Mertens F. Ewing Sarcoma. In: WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Fourth Edition. IARC, editor. 2013; 306-309. |

| 24. | Bovée JVMG. Jason L. Hornick: Practical soft tissue pathology: a diagnostic approach, 2nd edition. Virchows Arch. 2018;473:785-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sethi P, Singh A, Srinivas BH, Ganesh RN, Kayal S. Practical Approach in Management of Extraosseous Ewing's Sarcoma of Head and Neck: A Case Series and Review of literature. Gulf J Oncolog. 2022;1:79-88. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Thompson LD. Small round blue cell tumors of the sinonasal tract: a differential diagnosis approach. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:S1-S26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Casali PG, Bielack S, Abecassis N, Aro HT, Bauer S, Biagini R, Bonvalot S, Boukovinas I, Bovee JVMG, Brennan B, Brodowicz T, Broto JM, Brugières L, Buonadonna A, De Álava E, Dei Tos AP, Del Muro XG, Dileo P, Dhooge C, Eriksson M, Fagioli F, Fedenko A, Ferraresi V, Ferrari A, Ferrari S, Frezza AM, Gaspar N, Gasperoni S, Gelderblom H, Gil T, Grignani G, Gronchi A, Haas RL, Hassan B, Hecker-Nolting S, Hohenberger P, Issels R, Joensuu H, Jones RL, Judson I, Jutte P, Kaal S, Kager L, Kasper B, Kopeckova K, Krákorová DA, Ladenstein R, Le Cesne A, Lugowska I, Merimsky O, Montemurro M, Morland B, Pantaleo MA, Piana R, Picci P, Piperno-Neumann S, Pousa AL, Reichardt P, Robinson MH, Rutkowski P, Safwat AA, Schöffski P, Sleijfer S, Stacchiotti S, Strauss SJ, Sundby Hall K, Unk M, Van Coevorden F, van der Graaf WTA, Whelan J, Wardelmann E, Zaikova O, Blay JY; ESMO Guidelines Committee, PaedCan and ERN EURACAN. Bone sarcomas: ESMO-PaedCan-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:iv79-iv95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 52.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Muratori F, Mondanelli N, Pelagatti L, Frenos F, Matera D, Beltrami G, Innocenti M, Capanna R, Roselli G, Scoccianti G, Livi L, Greto D, Muntoni C, Baldi G, Tamburini A, Campanacci DA. Clinical features, prognostic factors and outcome in a series of 29 extra-skeletal Ewing Sarcoma. Adequate margins and surgery-radiotherapy association improve overall survival. J Orthop. 2020;21:236-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |