Published online Jan 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i1.157

Peer-review started: August 23, 2022

First decision: October 28, 2022

Revised: November 12, 2022

Accepted: December 15, 2022

Article in press: December 15, 2022

Published online: January 6, 2023

Processing time: 134 Days and 15.6 Hours

Ciprofol is a novel agent for intravenous general anesthesia. In February 2022, it was approved by the National Medical Products Administration for general anesthesia induction and maintenance. It has the advantages of fast onset, fast elimination, stable circulation, and few adverse reactions. However, the efficacy and safety of ciprofol in cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass have not been reported. Here we describe a case where ciprofol was successfully used for anesthesia in cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass.

A 72-year-old man (height 176 cm; weight 70 kg) was diagnosed with coronary atherosclerotic cardiomyopathy requiring coronary artery bypass grafting and left ventricular aneurysmectomy. Ciprofol was administered for induction (0.4 mg/kg) and maintenance (0.6-1.0 mg/kg/h) of general anesthesia. During the entire operation, the bispectral index, hemodynamics, and blood oxygen sat

Ciprofol is safe and effective for anesthesia in cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass.

Core Tip: Ciprofol is a novel agent for intravenous general anesthesia. It is characterized by fast onset, fast elimination, stable circulation, and few adverse reactions. This is the first case report of ciprofol administration for anesthesia in cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Based on our experience in this case, we conclude that ciprofol is safe and effective for anesthesia in cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. With further testing, ciprofol may replace propofol in the field of anesthesia for cardiac surgeries.

- Citation: Yu L, Bischof E, Lu HH. Anesthesia with ciprofol in cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(1): 157-163

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i1/157.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i1.157

True aneurysms of the left ventricle develop after complete myocardial infarctions. Sequelae include thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and congestive heart failure[1]. Left ventricular aneurysmectomy is the most effective method for the treatment of left ventricular aneurysm. Propofol has been the general anesthetic of choice for cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). Ciprofol introduces a cyclopropyl group based on the chemical structure of propofol forming a chiral structure, which increases the steric effect and thereby enhancing the affinity with GABAA receptors[2]. Compared with propofol, ciprofol has a wider safety window, a very low incidence of injection pain, better effects on breathing, and non-inferior effects on heart rate and blood pressure[3,4].

In a phase 3 clinical trial of ciprofol for induction of general anesthesia in elective surgery, Wang et al[4] found that the anesthesia induction success rates for ciprofol (0.4 mg/kg) and propofol (2 mg/kg) were both 100.0%, indicating that ciprofol was non-inferior to propofol. The average time to successful anesthesia and loss of the eyelash reflex were 0.91 min and 0.80 min for ciprofol and 0.80 min and 0.71 min for propofol, respectively. Ciprofol had a similar pattern of bispectral index (BIS) changes with ciprofol as with propofol, and its effect was stable during the anesthesia maintenance period. Safety was comparable between the two agents, with a rate of 88.6% treatment emergent adverse events in the ciprofol group and 95.5% in the propofol group. The incidence of injection pain was significantly lower in the ciprofol group compared to the propofol group (6.8% vs 20.5%, P < 0.05)[4]. Therefore, we considered that ciprofol could be a suitable anesthetic for CPB cardiac surgery.

Ciprofol is a newly developed intravenous anesthetic. It was approved by the National Medical Products Administration for general anesthesia induction and maintenance in February 2022. At present, there are no reports of ciprofol used for anesthesia in cardiac surgery with CPB. Here we describe a case where ciprofol was successfully administered for anesthesia in cardiac surgery with CPB.

The patient was a 72-year-old male. More than 6 mo after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, a left ventricular aneurysm was found during follow-up.

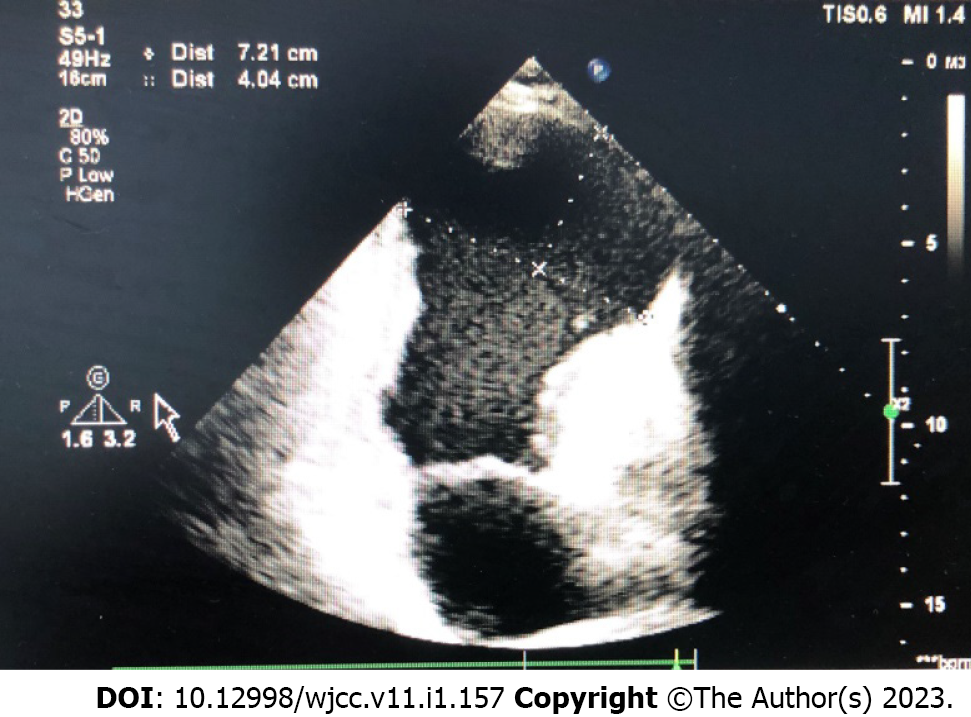

Six months prior, the patient went to the Cardiology Department due to chest pain and was diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction. On the same day, emergency coronary angiography and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty were performed, and the patient recovered after surgery. He attended the hospital for a follow-up visit 1 d prior. Echocardiography showed that the left ventricular inner diameter had increased, the motion of the middle and lower segments of the interventricular septum and the middle and lower ends of the left ventricular wall was weakened, and the left ventricular apex myocardium was thinned, bulging outward, and showing paradoxical motion, with a range of 70.7 mm × 40.9 mm. The ejection fraction was 27%. He was diagnosed with left ventricular aneurysm, and surgery was recommended.

The patient developed acute myocardial infarction more than 6 mo ago and underwent concurrent coronary angiography and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.

The patient denied any family history of cardiovascular disease.

The patient had a temperature of 36.2 °C, heart rate of 81 bpm, blood pressure of 128/65 mmHg with respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min. His height was 176 cm and weight was 70 kg. The patient was fully conscious. The breath sounds were vesicular with no added sound. Heart sounds were normal first and second with no murmur.

Arterial oxygen partial pressure was 80.2 mmHg, carbon dioxide partial pressure was 50.4 mmHg, potassium was 3.3 mmol/L, and pro-brain natriuretic peptide was 694 ng/L.

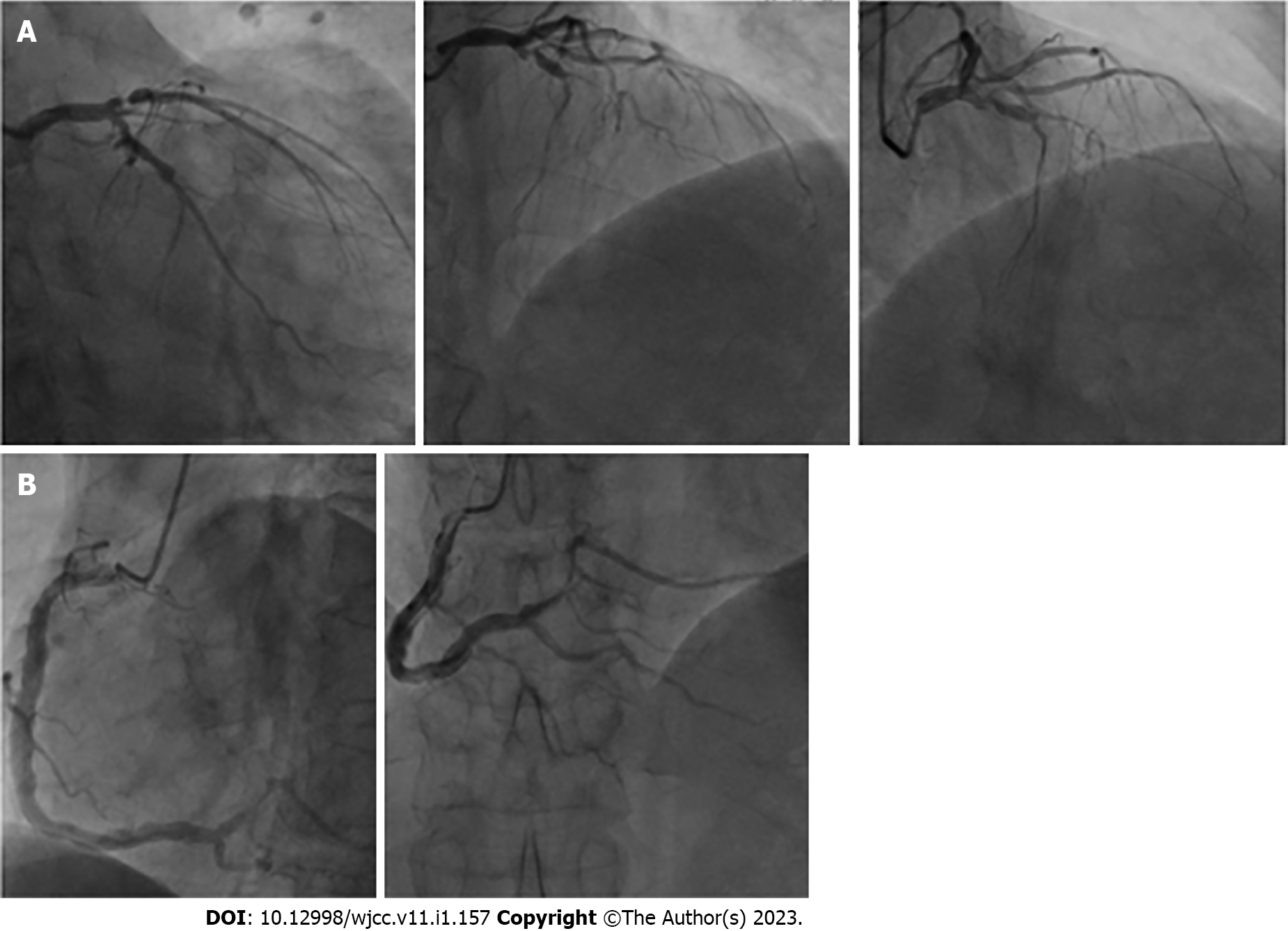

Preoperative echocardiography showed that the left ventricular volume was significantly increased, systolic function was significantly reduced, and the formation of a huge ventricular aneurysm was seen at the apex (Figure 1). Coronary angiography showed 70%-80% stenosis in the proximal segment of the anterior descending artery, 100% stenosis in the proximal and middle segments, 70% stenosis in the proximal segment of D1, and 70% stenosis in the middle segment of the circumflex artery. Right coronary artery aneurysm-like expansion, proximal 40%-50% stenosis, and 30%-40% stenosis in the distal segment were observed (Figure 2).

Coronary heart disease and left ventricular aneurysm.

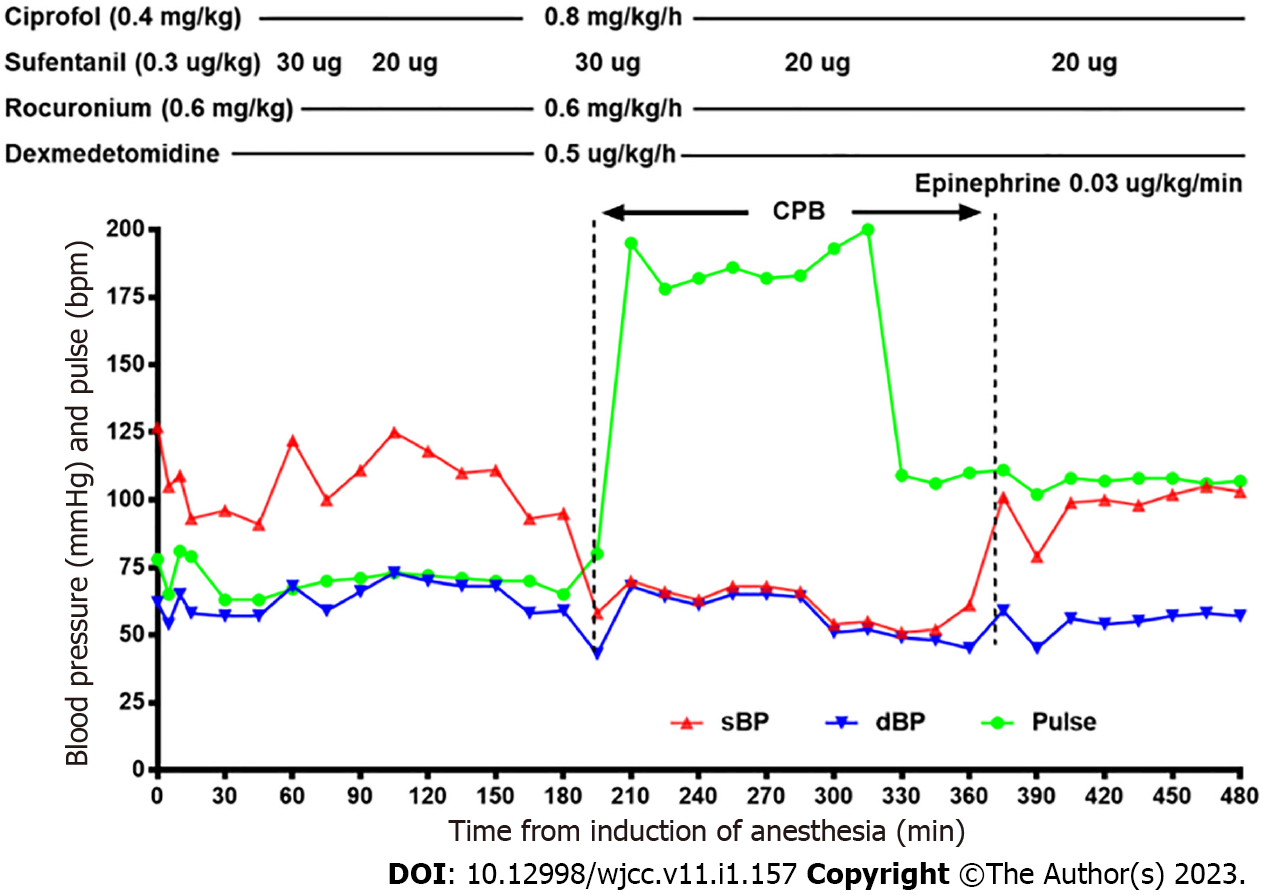

The patient underwent coronary artery bypass grafting and left ventricular aneurysmectomy. He was fasted for 8 h before surgery with no liquids 2 h before surgery. When the patient entered the operating room, his electrocardiogram, pulse oximetry, and BIS were monitored. After local anesthesia with lidocaine, left radial artery cannulation was performed for arterial blood pressure monitoring. Anesthesia induction was started after opening one peripheral vein. We administered 0.4 mg/kg ciprofol, 0.3 μg/kg sufentanil, and 0.6 mg/kg rocuronium bromide for induction of anesthesia. There was no injection pain during the administration of ciprofol. After successful induction, a 7.0 tracheal tube was selected for tracheal intubation with the aid of a video laryngoscope, and a transesophageal ultrasound probe was placed. Following tracheal intubation, the right internal jugular vein was punctured, a 3-lumen catheter was inserted, and central venous pressure was monitored. We maintained anesthesia with ciprofol 0.8 mg/kg/h, dexmedetomidine 0.5 μg/kg/h, rocuronium 0.6 mg/kg/h, and intermittent sufentanil. We used 3 mg/kg heparin for anticoagulation and established CPB through aortic and right atrium cannulation after an activated clotting time > 480 s. Coronary artery bypass grafting (left anterior descending artery, left circumflex artery, and right coronary artery) and left ventricular aneurysmectomy were performed under mild hypothermia (32 °C-35 °C) CPB and cold crystalloid arrest. After aortic patency, we used 0.03 μg/kg/min epinephrine to promote cardiac restart. CPB was stopped when hemodynamics were stable and the body temperature was above 36 °C. We used 1.0 g tranexamic acid before and at the end of CPB. After CPB, 40 mg methylprednisolone and 450 mg protamine were administered.

The operation went smoothly, and the intraoperative BIS was maintained at 40-60. During surgery, we administered phenylephrine if the blood pressure was too low (systolic blood pressure below 90 mmHg) and anisodamine when the heart rate was too slow (below 60 bpm). A total of 1000 mL crystalloid, 500 mL colloid, and 375 mL autologous blood were infused during the operation. Blood loss during surgery was 700 mL, and urine output was 800 mL. The total anesthesia time was 480 min, and CPB time was 175 min. After the operation, the infusion of ciprofol and rocuronium bromide was stopped, and infusion of dexmedetomidine 0.5 μg/kg/h and epinephrine 0.03 μg/kg/min were continued. The patient was hemodynamically stable and intubated, and then transported from the operating room to the intensive care unit (ICU). The anesthetic record is shown in Figure 3.

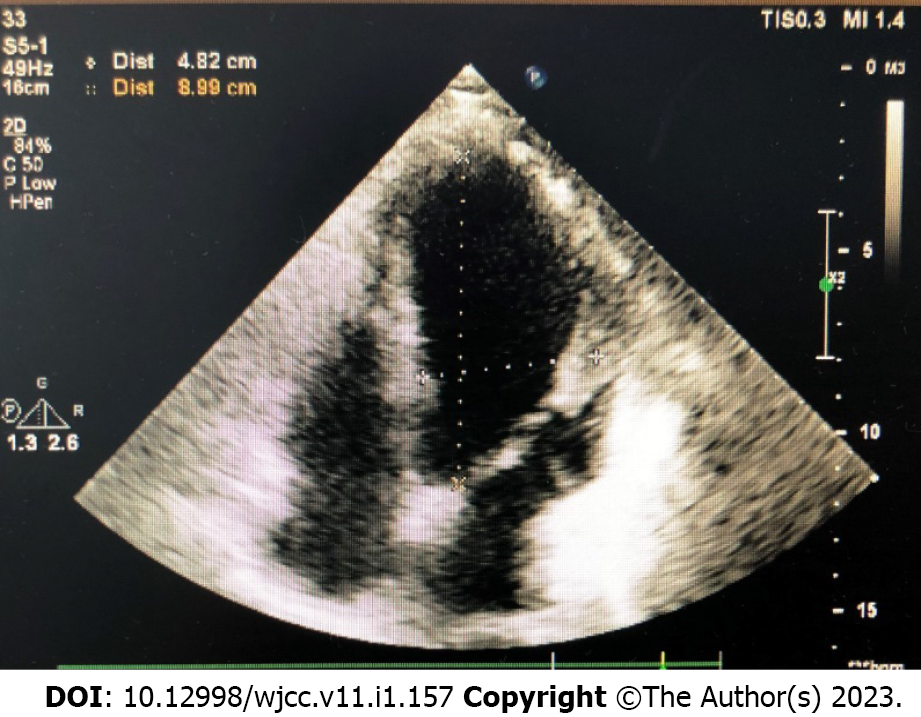

The tracheal tube was removed 2 h after the patient was transferred to the ICU. The patient was transferred from the ICU to the general ward on the 2nd postoperative day and was discharged on the 9th postoperative day. The patient was discharged with a blood pressure of 101/68 mmHg, heart rate of 70 bpm, New York Heart Association class II, and no adverse events associated with ciprofol. Postoperative echocardiography showed that after left ventricular aneurysmectomy and coronary artery bypass grafting, his ejection fraction was 40% (Figure 4).

This is the first case report of ciprofol administration for anesthesia in cardiac surgery with CPB. Ciprofol is a GABA receptor agonist and is a novel 2,6-disubstituted phenol derivative, like propofol[5]. Furthermore, the metabolites of ciprofol are nonhypnotic and nontoxic[6]. In February 2022, it was approved by the National Medical Products Administration for the maintenance of general anesthesia. At present, there are no reports on the use of ciprofol for anesthesia in CPB surgery. We selected a patient who required coronary artery bypass grafting and left ventricular aneurysmectomy and was administered ciprofol for induction and maintenance of anesthesia, in an attempt to know the anesthetic effect of ciprofol in this type of surgery. The results showed that the patient was hemodynamically stable during anesthesia induction and maintenance, the depth of anesthesia was appropriate, and there were no adverse reactions related to ciprofol infusion.

To avoid injection pain caused by propofol, we usually administer a small dose of sufentanil before propofol injection during the induction of anesthesia. In the present case, we injected ciprofol first followed by sufentanil. The patient did not complain of pain during the induction of anesthesia. This is consistent with related studies showing a low incidence of injection pain with ciprofol[4]. The difference in incidence of injection pain between the two drugs may be due to different drug concentrations in the aqueous phase of the injection solution[7].

We successfully induced anesthesia using ciprofol at 0.4 mg/kg. After 38 s, the patient’s eyelash reflex disappeared, and the BIS was 40. Studies have shown that the potency of ciprofol is 4-5 times that of propofol. Ciprofol enhances GABAA receptor-mediated cellular currents five-fold more than propofol[3]. Ciprofol 0.4-0.5 mg/kg induced equivalent sedation/anesthesia and had a similar safety profile to propofol 2.0 mg/kg[7].

During induction of anesthesia, the patient’s blood pressure decreased from 128/64 mmHg to 103/55 mmHg and his heart rate decreased from 79 bpm to 65 bpm. Severe hypotension and bradycardia were not observed. Tracheal intubation resulted in an increase in blood pressure to 110/66 mmHg and heart rate to 83 bpm. This indicated that induction of anesthesia with ciprofol may have less impact on hemodynamics and less responsiveness to intubation. It is worth mentioning that the hemodynamics during maintenance of anesthesia was more stable than expected throughout the surgery with CPB, and only a total dosage of 80 μg phenylephrine was administered during the operation. Some studies have shown comparable safety, tolerability, and treatment emergent adverse event rates between ciprofol and propofol[8,9]. However, this case suggests that ciprofol may have a weaker inhibitory effect on the cardiovascular system than propofol and a lower incidence of treatment emergent adverse events. This may be an accidental event. Further research is needed on the effect of ciprofol on circulatory stability during cardiac surgery with CPB. We only pumped 0.03 μg/kg/min of epinephrine to promote heartbeat recovery. We did not use additional vasoactive drugs to maintain blood pressure and heart rate when CPB was discontinued. Whether ciprofol is more beneficial for heartbeat recovery and hemodynamic stabilization after CPB is unclear. In the present case, after surgery the infusion of ciprofol and rocuronium bromide was stopped, and infusion of dexmedetomidine 0.5 μg/kg/h and epinephrine 0.03 μg/kg/min was continued. The patient was intubated and transported to the ICU. Therefore, we do not know the awakening time from ciprofol anesthesia. This requires further research.

During anesthesia, BIS was maintained below 60, and the patient did not have intraoperative awareness after surgery. Studies have shown that the BIS change pattern with ciprofol is similar to that of propofol[4]. We believe that BIS can be used to monitor the depth of anesthesia with ciprofol.

Propofol infusion syndrome is a serious adverse reaction caused by prolonged infusion of propofol[10]. Whether ciprofol can cause a similar situation is unclear, and there are no relevant reports. Therefore, further investigation is required.

In addition, the dosage of epinephrine and phenylephrine used in this type of surgery needs to be determined according to the hemodynamic status of the patient during the operation. The doses of epinephrine and phenylephrine used in our patient were relatively small. Throughout the anesthesia, the patient was hemodynamically stable, and the heart resumed beating smoothly. Thus, whether ciprofol is more suitable and safer than propofol for anesthesia in cardiac surgery deserves further study.

Ciprofol may be a safe and effective agent for anesthesia in cardiac surgery with CPB. Ciprofol can be administered for induction and maintenance of anesthesia in CPB surgery. Ciprofol may have advantages over propofol for hemodynamic stabilization during anesthesia maintenance during cardiopulmonary bypass. With further research, ciprofol may replace propofol in the field of cardiac anesthesia.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Anesthesiology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abubakar MS, Nigeria; Amornyotin S, Thailand; Barik R, India S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Hui DS, Restrepo CS, Calhoon JH. Surgical Decision Making for Left Ventricular Aneurysmectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110:e559-e561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wei Y, Qiu G, Lei B, Qin L, Chu H, Lu Y, Zhu G, Gao Q, Huang Q, Qian G, Liao P, Luo X, Zhang X, Zhang C, Li Y, Zheng S, Yu Y, Tang P, Ni J, Yan P, Zhou Y, Li P, Huang X, Gong A, Liu J. Oral Delivery of Propofol with Methoxymethylphosphonic Acid as the Delivery Vehicle. J Med Chem. 2017;60:8580-8590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Qin L, Ren L, Wan S, Liu G, Luo X, Liu Z, Li F, Yu Y, Liu J, Wei Y. Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Novel 2,6-Disubstituted Phenol Derivatives as General Anesthetics. J Med Chem. 2017;60:3606-3617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang X, Wang X, Liu J, Zuo YX, Zhu QM, Wei XC, Zou XH, Luo AL, Zhang FX, Li YL, Zheng H, Li H, Wang S, Wang DX, Guo QL, Liu CM, Wang YT, Zhu ZQ, Wang GY, Ai YQ, Xu MJ. Effects of ciprofol for the induction of general anesthesia in patients scheduled for elective surgery compared to propofol: a phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, comparative study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:1607-1617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nair A, Seelam S. Ciprofol- a game changing intravenous anesthetic or another experimental drug! Saudi J Anaesth. 2022;16:258-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bian Y, Zhang H, Ma S, Jiao Y, Yan P, Liu X, Xiong Y, Gu Z, Yu Z, Huang C, Miao L. Mass balance, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravenous HSK3486, a novel anaesthetic, administered to healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87:93-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Teng Y, Ou M, Wang X, Zhang W, Liu X, Liang Y, Li K, Wang Y, Ouyang W, Weng H, Li J, Yao S, Meng J, Shangguan W, Zuo Y, Zhu T, Liu B, Liu J. Efficacy and safety of ciprofol for the sedation/anesthesia in patients undergoing colonoscopy: Phase IIa and IIb multi-center clinical trials. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2021;164:105904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hu C, Ou X, Teng Y, Shu S, Wang Y, Zhu X, Kang Y, Miao J. Sedation Effects Produced by a Ciprofol Initial Infusion or Bolus Dose Followed by Continuous Maintenance Infusion in Healthy Subjects: A Phase 1 Trial. Adv Ther. 2021;38:5484-5500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu Y, Yu X, Zhu D, Zeng J, Lin Q, Zang B, Chen C, Liu N, Liu X, Gao W, Guan X. Safety and efficacy of ciprofol vs. propofol for sedation in intensive care unit patients with mechanical ventilation: a multi-center, open label, randomized, phase 2 trial. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022;135:1043-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hemphill S, McMenamin L, Bellamy MC, Hopkins PM. Propofol infusion syndrome: a structured literature review and analysis of published case reports. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:448-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |